Categories

Subjects

Authors

Artists

Venues

Locations

Calendar

Filter

Done

November 20, 2024 – Review

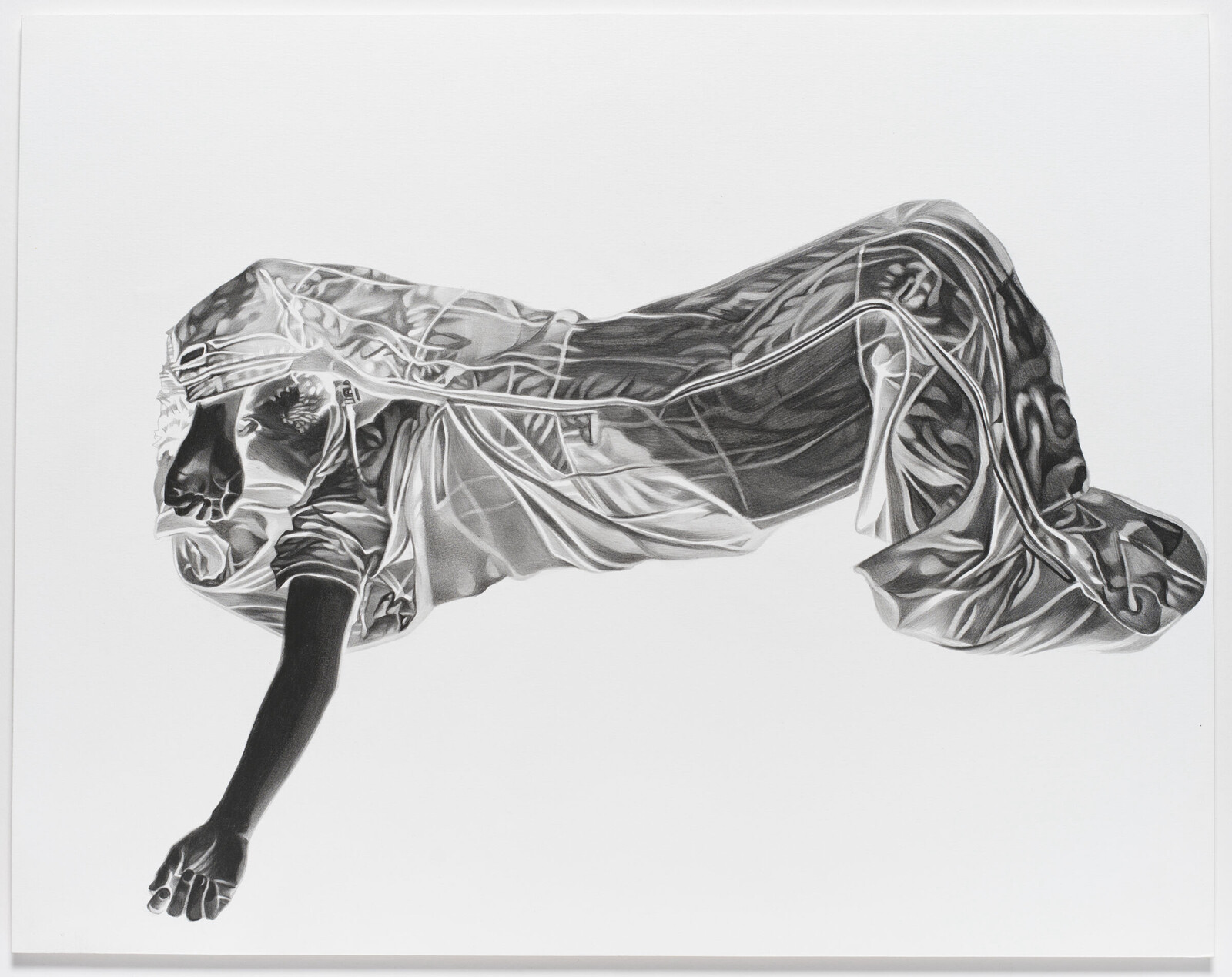

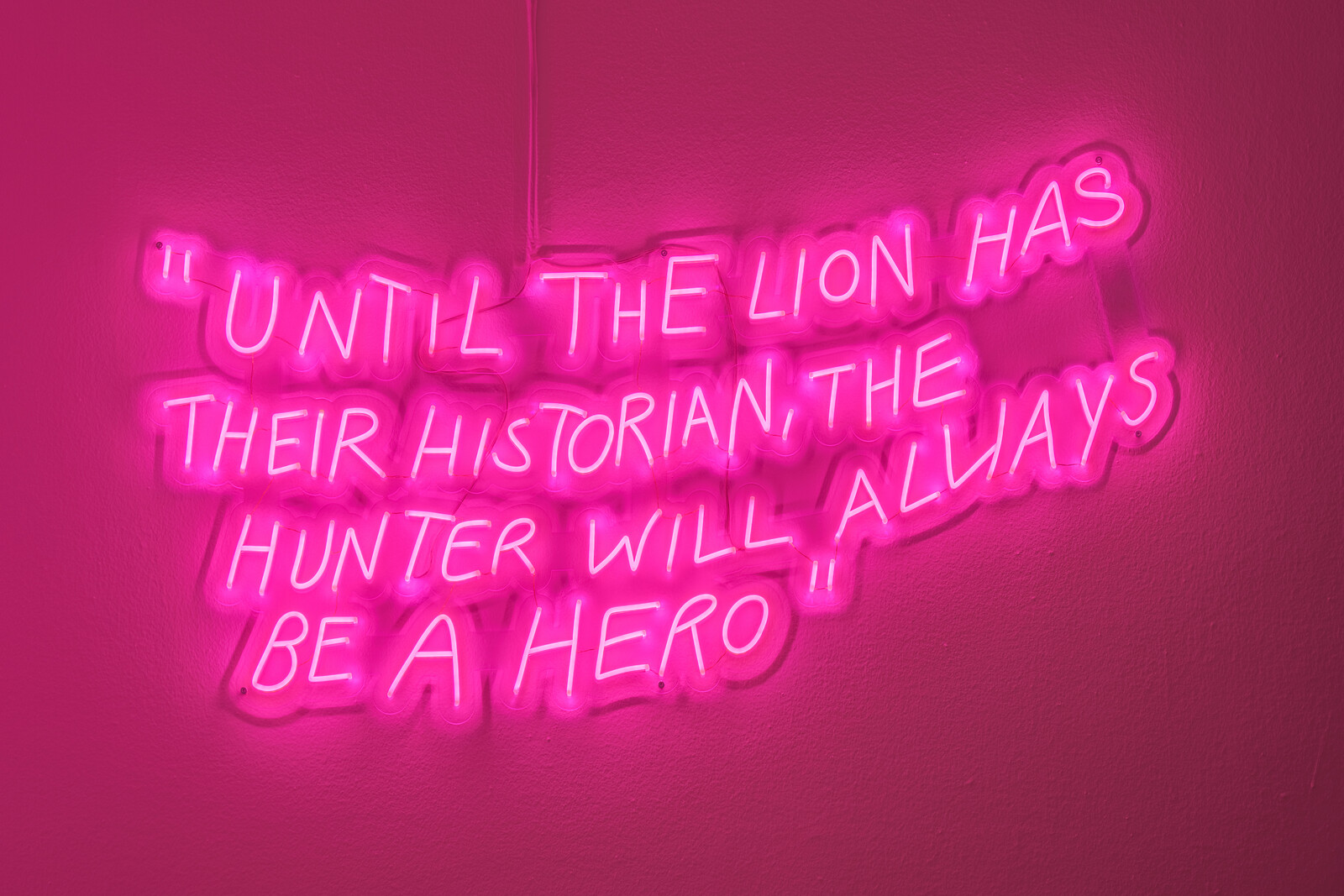

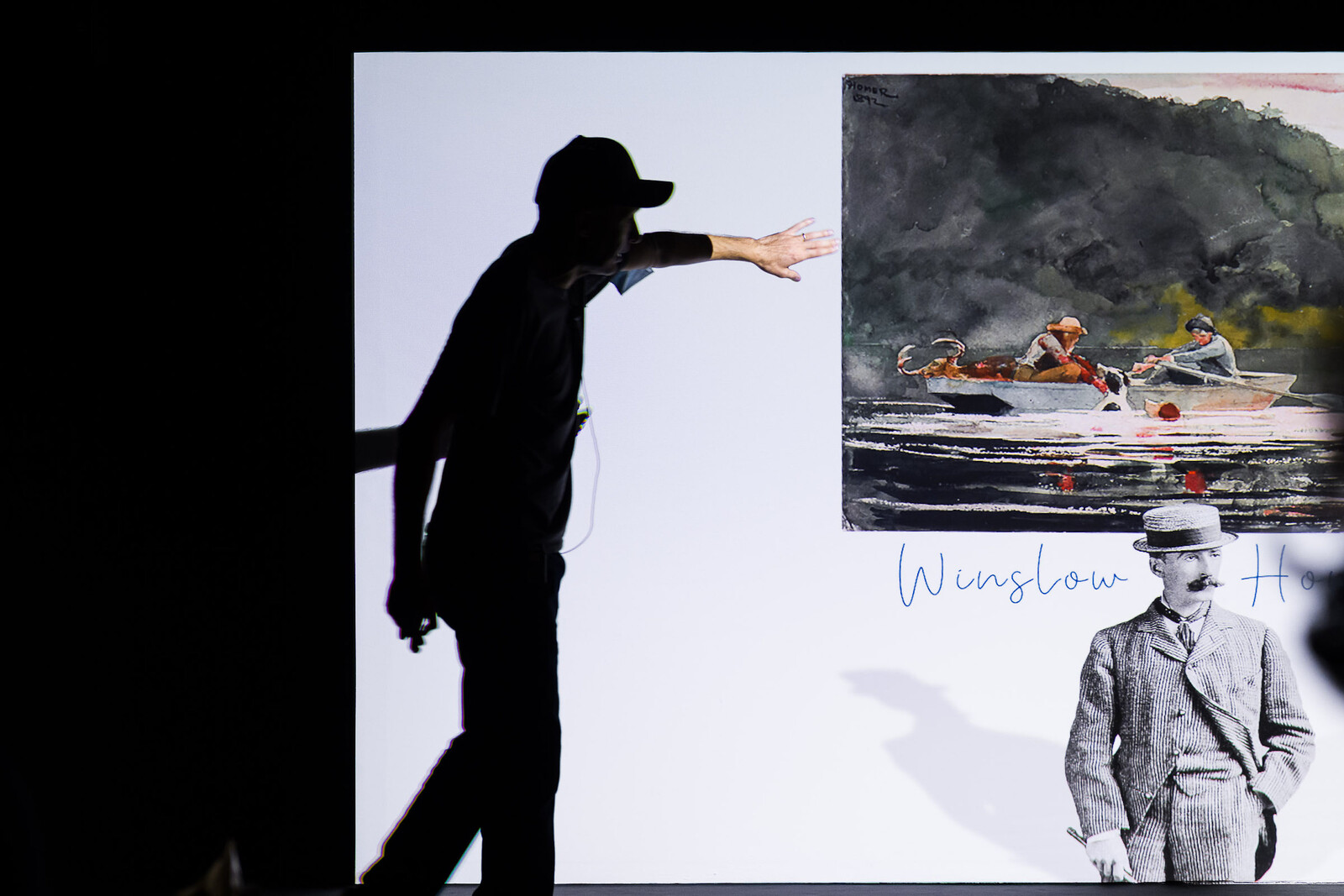

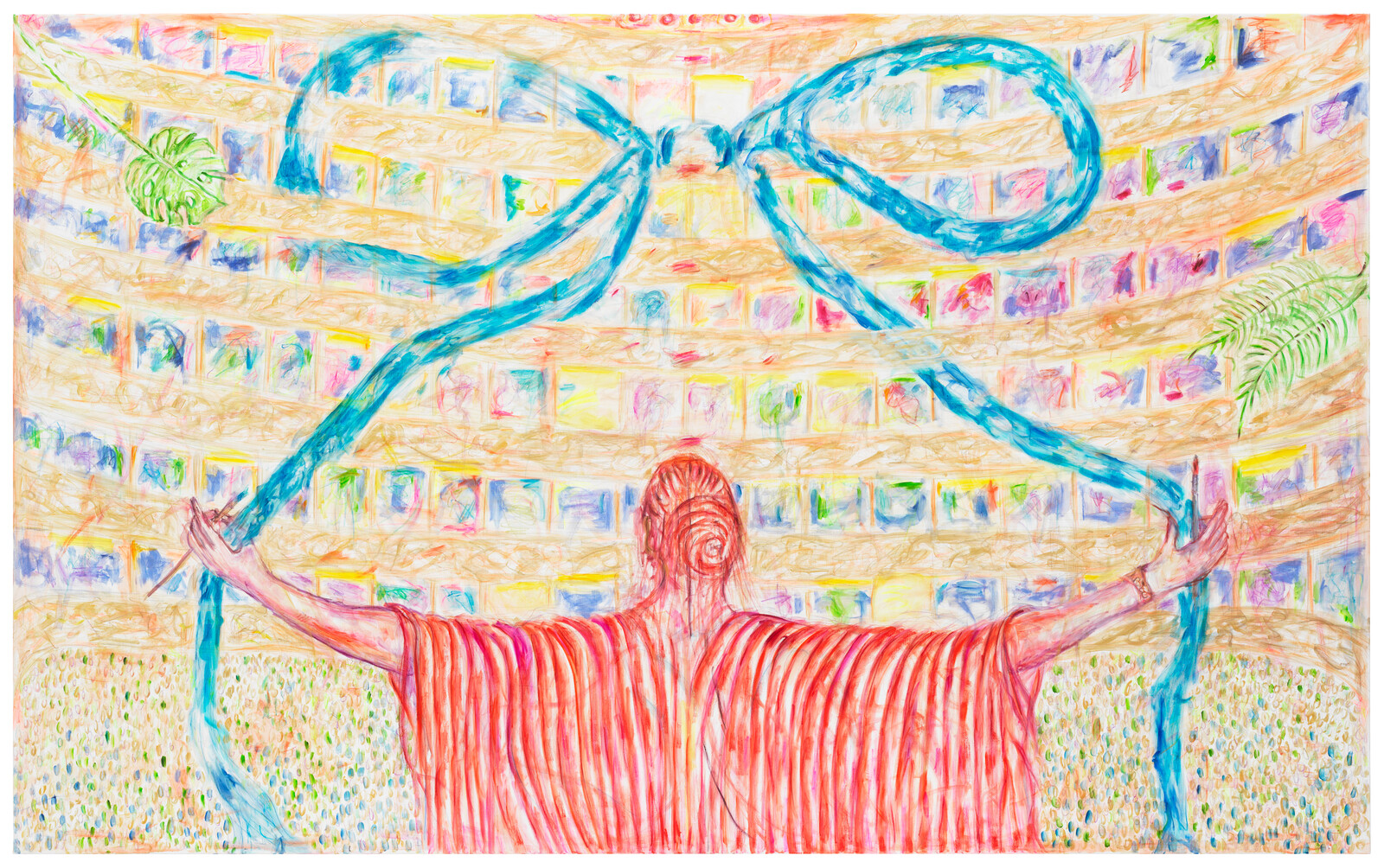

Glenn Ligon’s “All Over The Place”

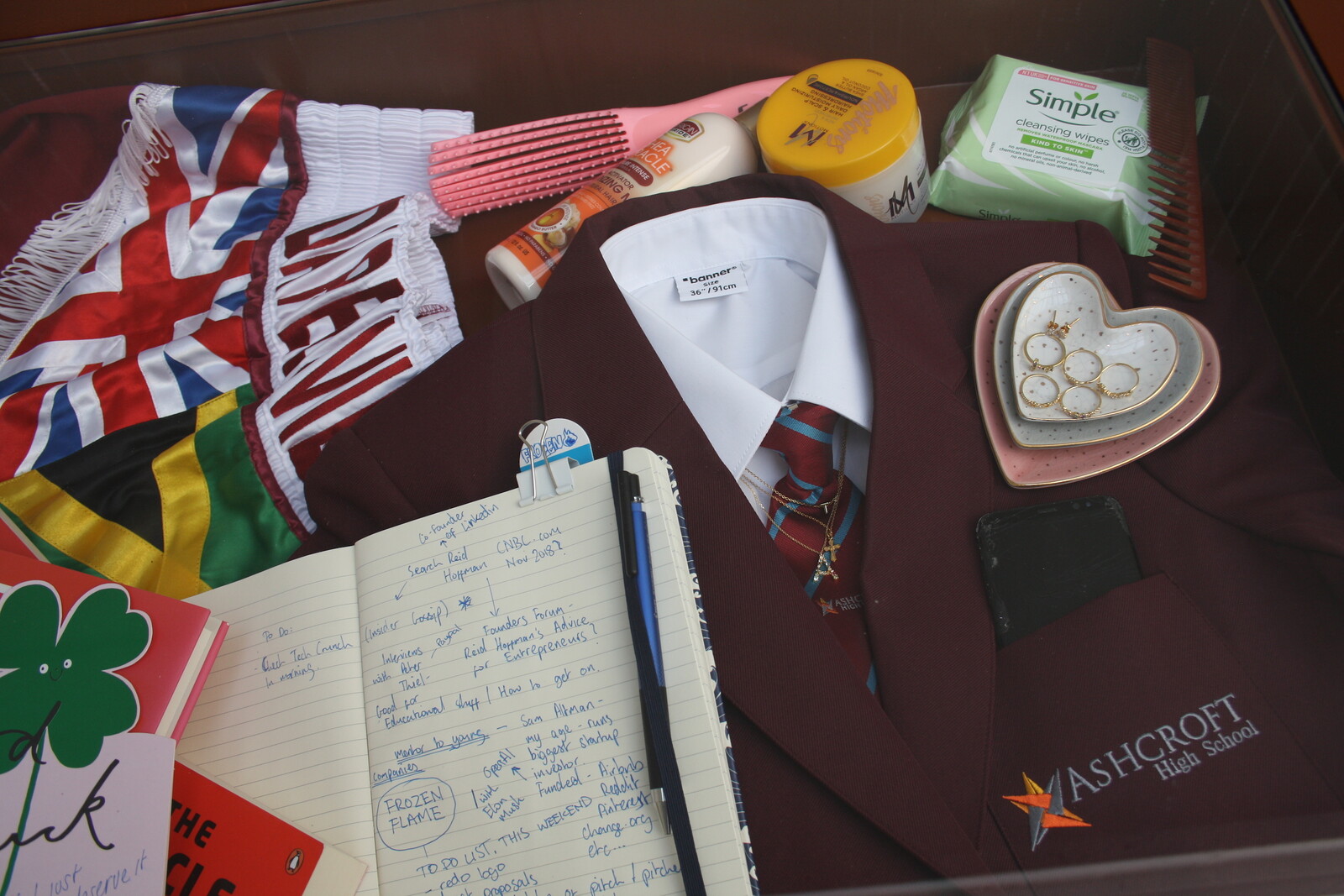

Novuyo Moyo

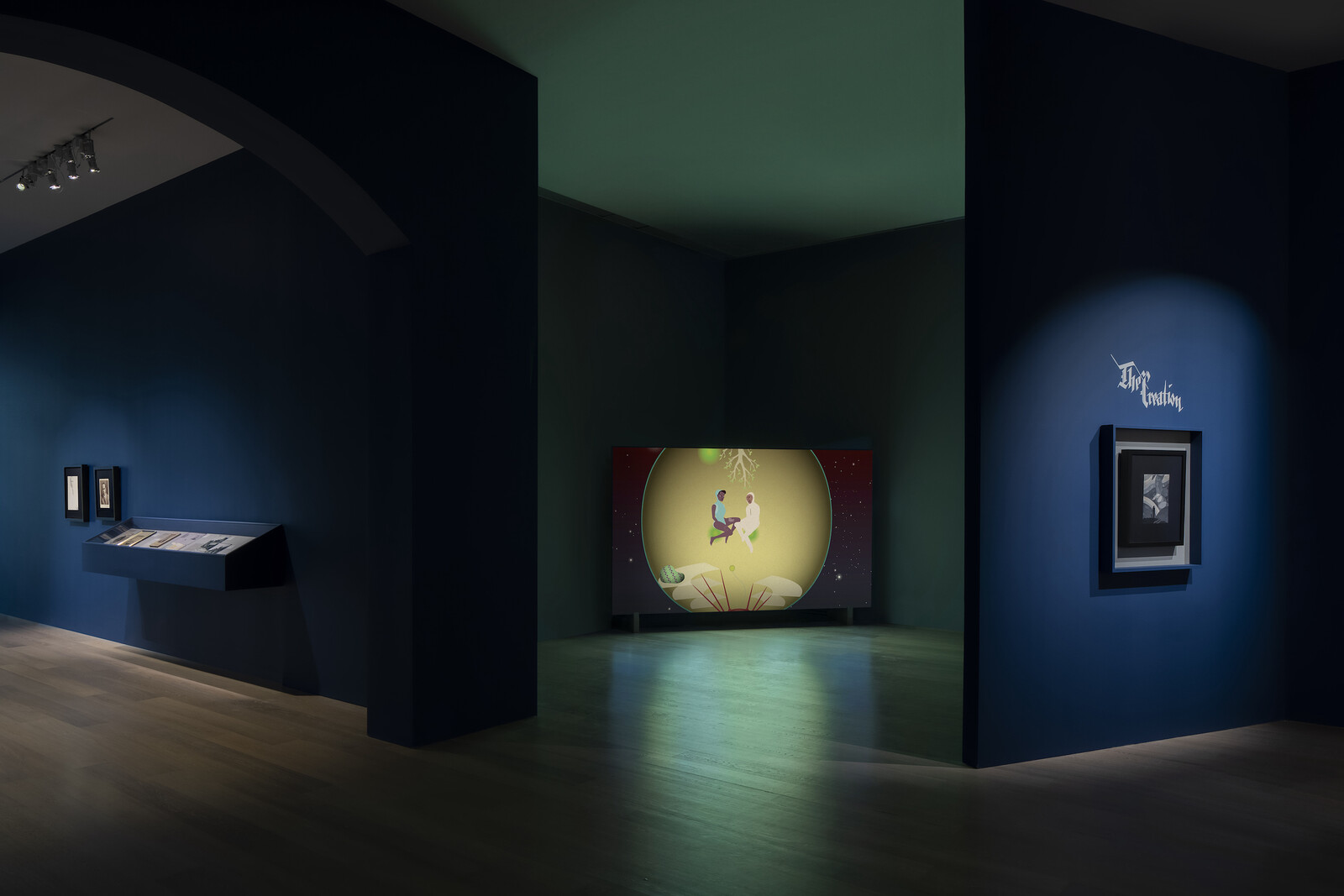

Glenn Ligon’s takeover of the Fitzwilliam Museum is so “all over the place” that I had to come back for a second visit to see things I’d missed the first time around. It is relevant to his nuanced but pervasive intervention that the museum was founded in 1816 when Viscount Richard Fitzwilliam left his collection of art and cultural artifacts to the University of Cambridge with a bequest to construct a museum of art and antiquities. This leaves it with twinned affiliation: both to an esteemed educational institution and to a landowner whose fortune derived in part—as recent research by the museum has unearthed—from his grandfather’s investment in the transatlantic slave trade.

Ligon’s multimedia work often interrogates race, even if it cannot be reduced to that subject, and his subtle interventions into the museum’s collection are consistent with his multilayered practice. On the ground floor, Ligon has selected objects from the museum’s collection of porcelain from Europe and Japan, showing them alongside his take on Korean Moon jars, painted a blackish hue instead of the traditional white. On the floor above, Ligon has rehung flower paintings from the collection of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Dutch still lifes, rearranging them to form …

November 19, 2024 – Review

Tbilisi Architecture Biennial 2024, “Correct Mistakes”

Océane Ragoucy

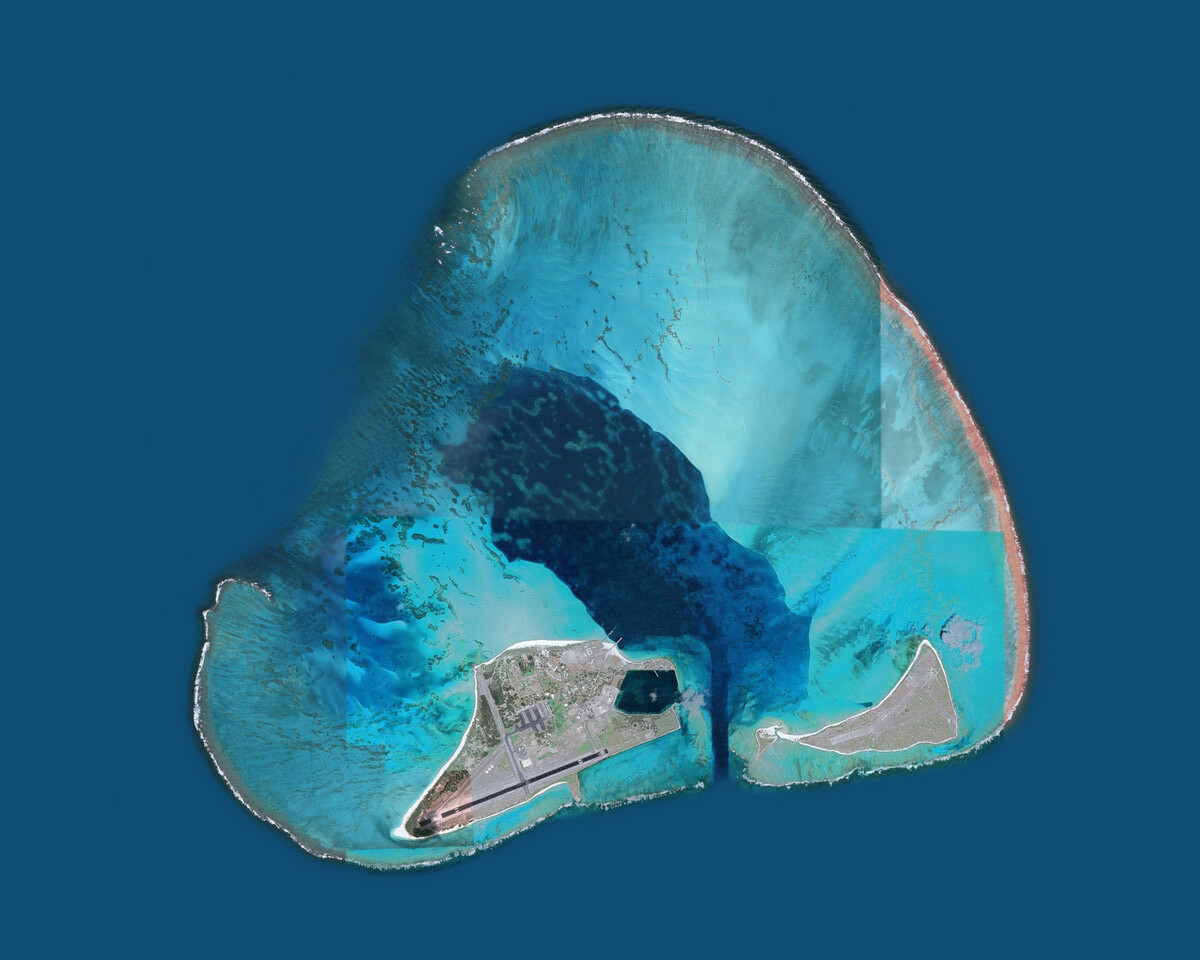

Barely twenty-four hours after it was declared that Georgia’s parliamentary elections had been won by Georgian Dream—a party founded by a pro-Russian billionaire—the country’s president, Salome Zourabichvili, denounced a “total falsification” of the vote and called on her fellow citizens to protest. It feels apt, therefore, that artistic directors Tinatin Gurgenidze, Otar Nemsadze, and Gigi Shukakidze should have chosen the theme of “Correct Mistakes” for the fourth Tbilisi Architecture Biennial, with its multiple meanings, from useful errors to their possible rectification. This edition focuses on the seizure of natural resources, landscapes exploited for profit, forgotten ecological histories and—more generally, as the biennial’s statement puts it—the “disregard for climate change.” Their radical, resolutely provocative approach points to the urgent role and responsibility of architects, urban actors, and activists in preserving the commons.

The biennial unfolds as a vibrant, multifaceted structure: exhibitions, screenings, workshops, symposia, off-the-beaten-track site visits, and “toxic tours” of polluted and damaged places in different parts of the city. The selected projects thus provide multiple access points to the complex connections between climate, resources, their extraction and appropriation, starting from Georgia but not restricted to it. National borders are never directly invoked. Rather, it is a matter of the …

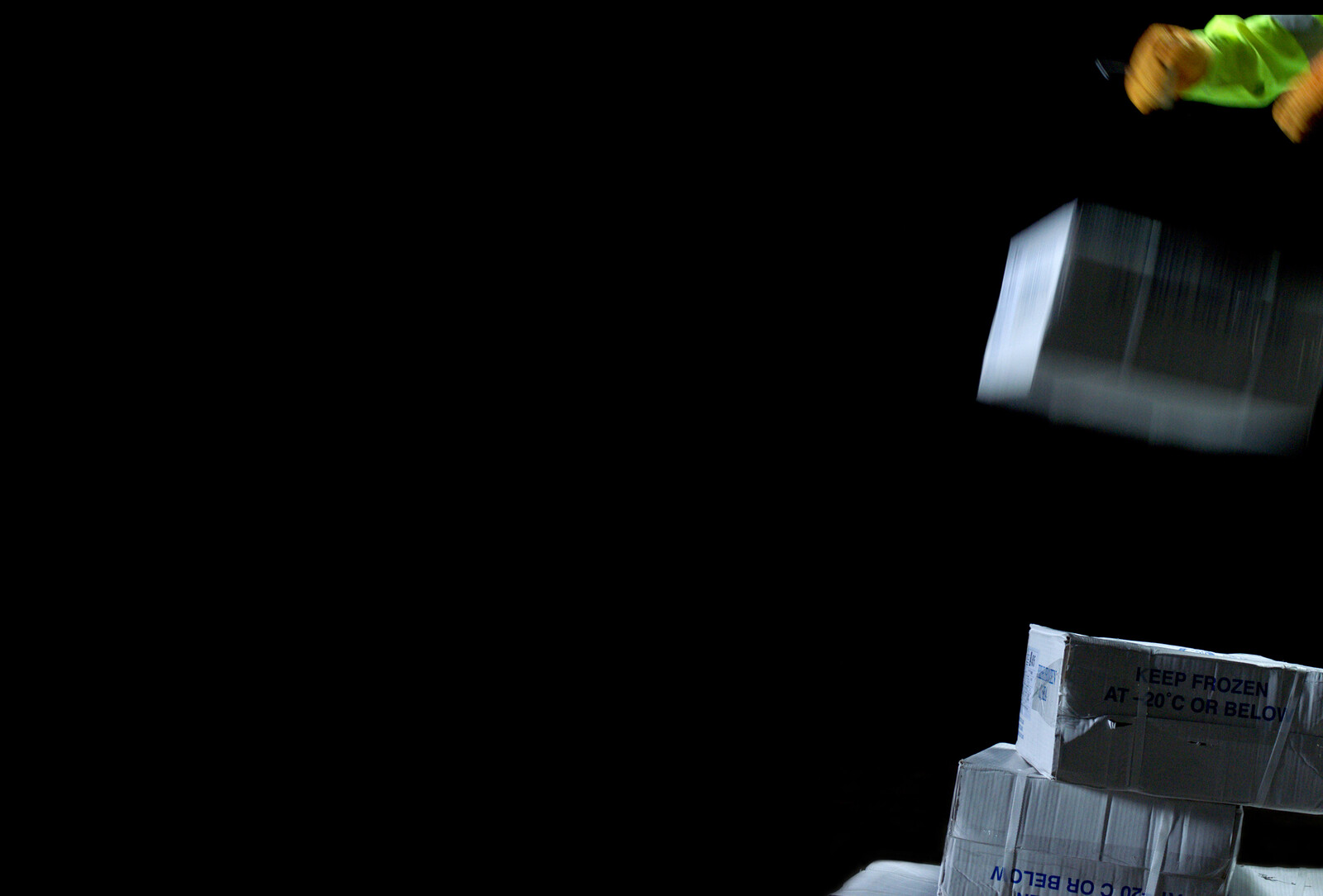

November 15, 2024 – Review

62nd New York Film Festival, “Currents”

Almudena Escobar López

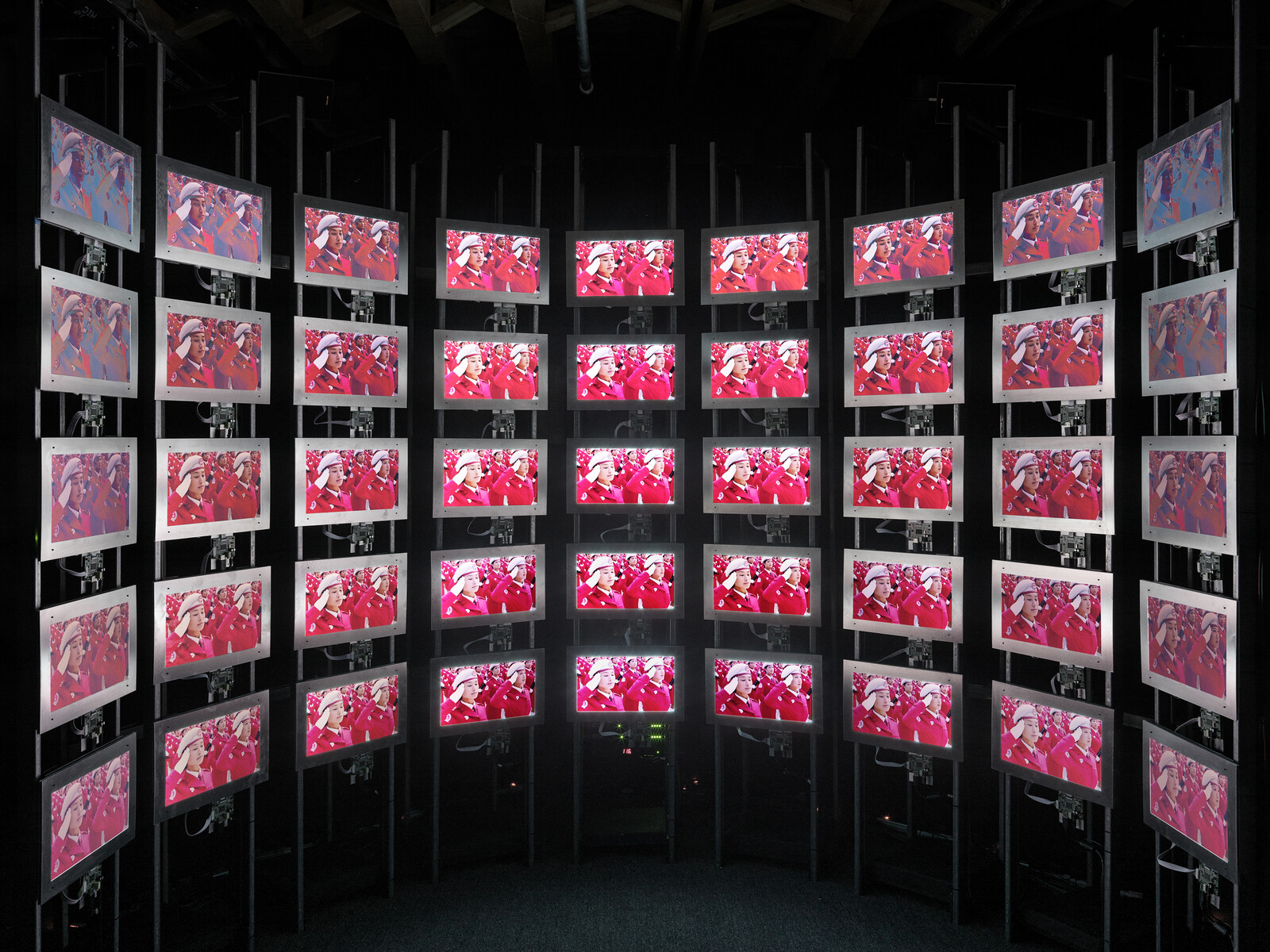

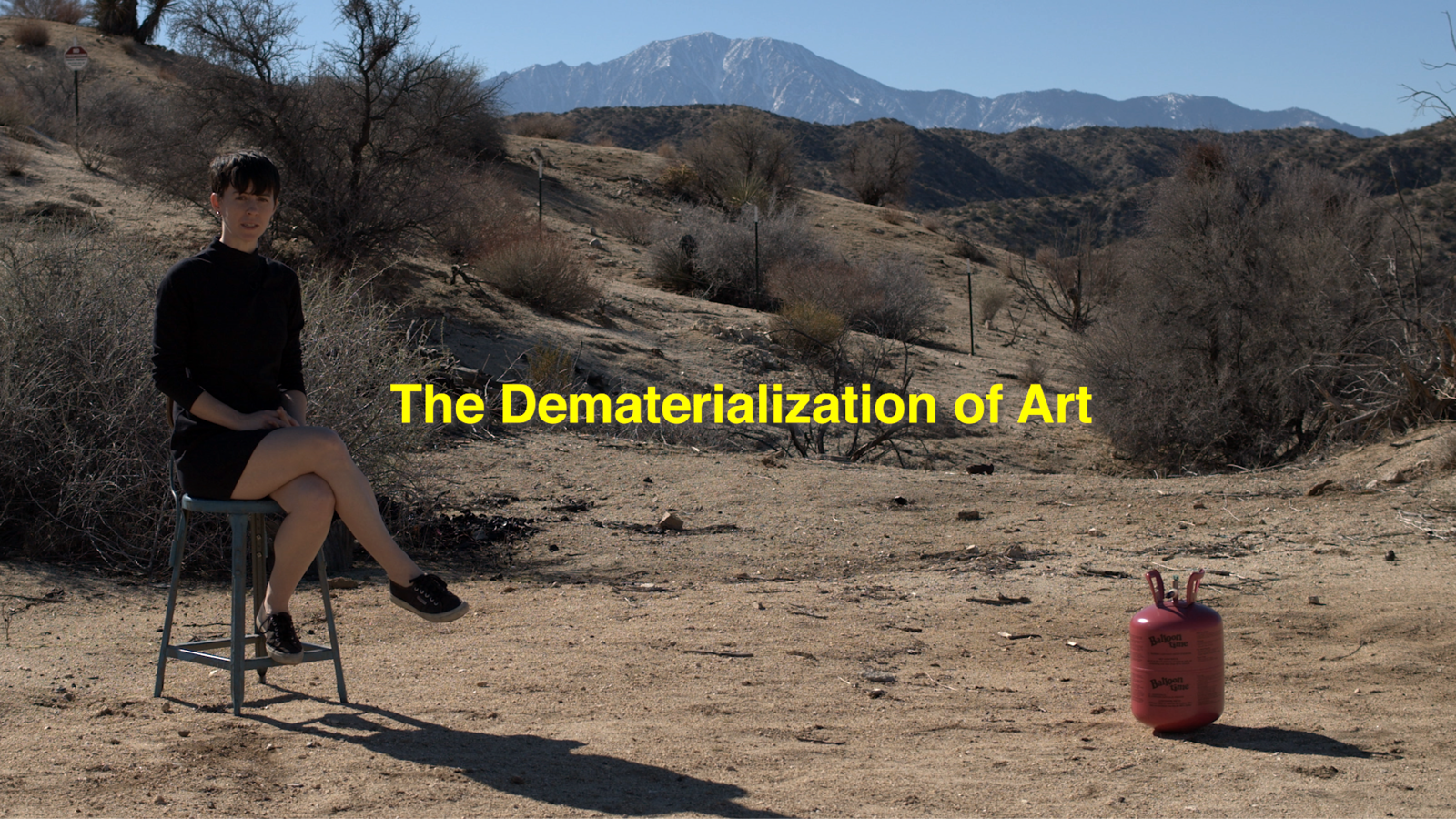

Days before the New York Film Festival opened, dozens of filmmakers—many from the “Currents” section—published a petition urging the festival to cut ties with Bloomberg Philanthropies due to concerns over its implication “in facilitating settlement infrastructure in the West Bank and denying Palestinians their basic rights.” During the fortnight, anti-war demonstrators interrupted Q&As and screenings, and a parallel Counter Film Festival was organized. How do we approach film-making after a year of live-streamed genocide in Gaza? This question lingered over the “Currents” shorts programs, curated by Aily Nash and Tyler Wilson, which seek to foreground “new and innovative forms and voices.” A select group of films from the programs challenged how images influence our perception of reality, particularly in contexts of violence, prompting critical reflection on our roles as viewers.

Two films in “The Will to Change” program reveal the limits of observation, turning the horror of witnessing war into an act of self-reflection. Black Glass (2024) by Adam Piron conjures the ghosts of the past (and the present) by speaking about the intrinsic relationship between early image-making technologies and the ongoing processes of settler colonialism. Piron examines Eadweard Muybridge’s early photographic work, commissioned by the US Army to capture …

November 14, 2024 – Review

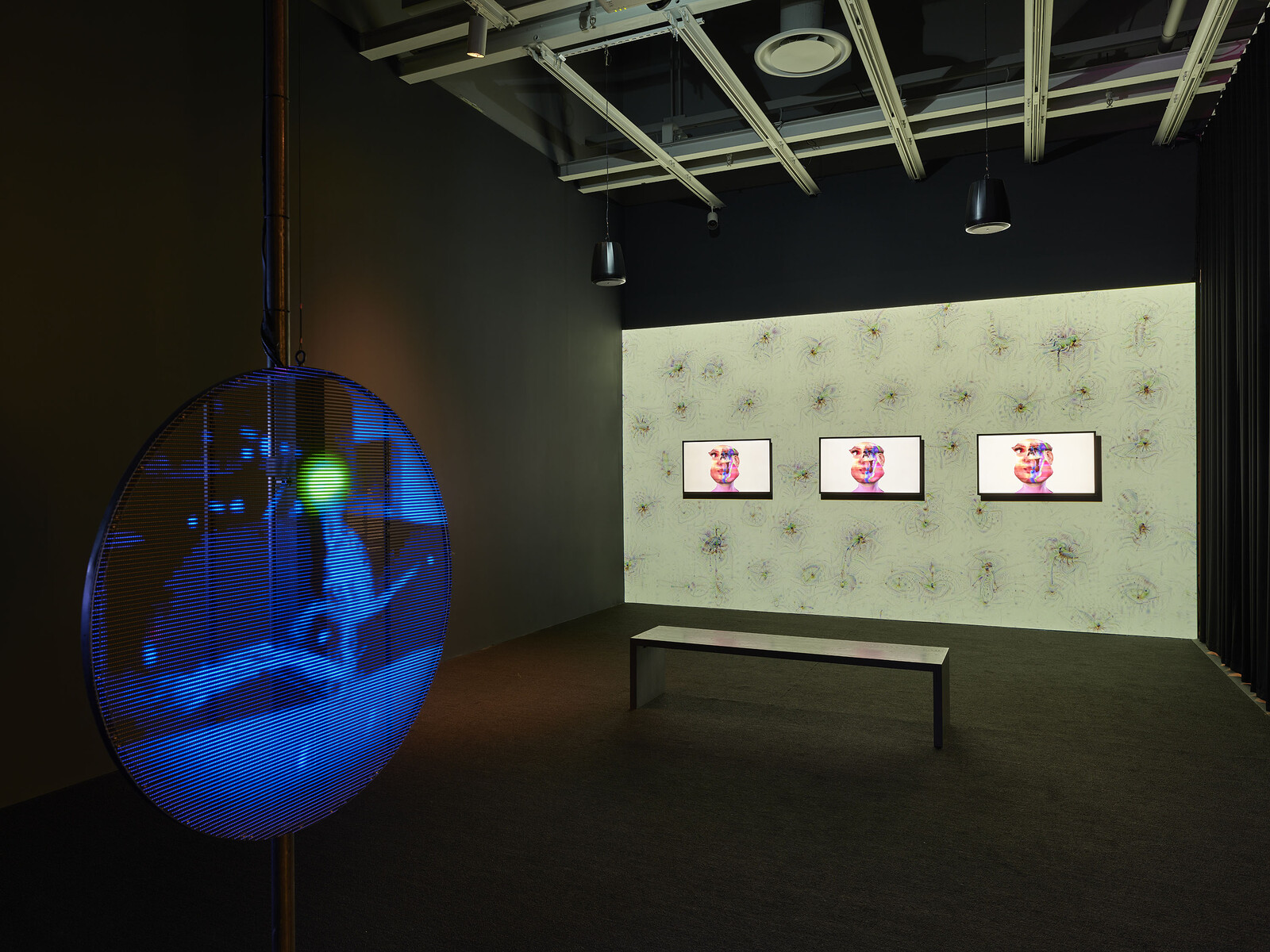

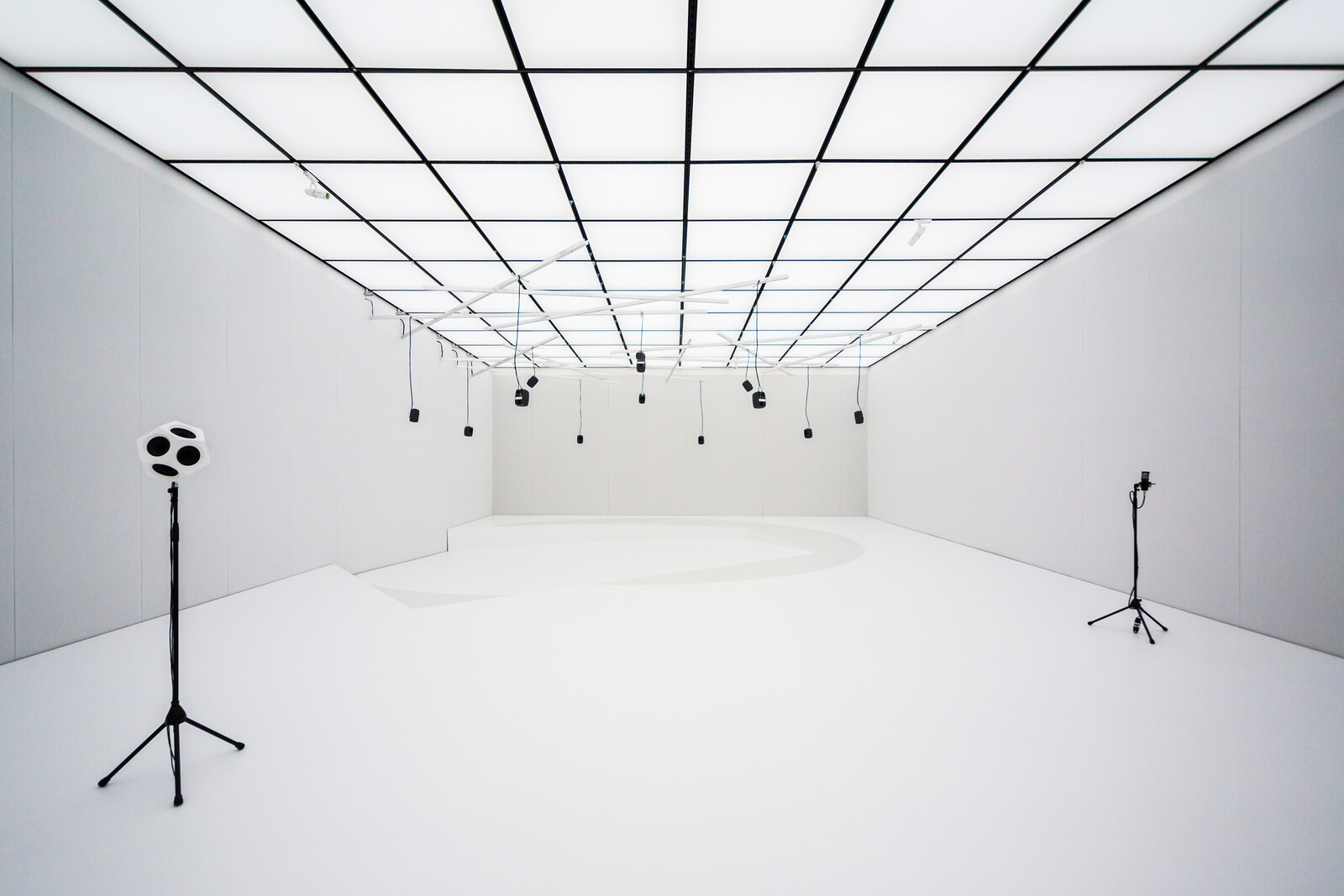

Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst’s “The Call”

George Kafka

Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst have in recent years been better known as spokespeople for the artistic possibilities of AI than as demonstrators of its uses. Numerous media profiles, their Interdependence podcast, and Dryhurst’s busy X account mean it has been easier to learn their opinions on AI than to engage with—and sometimes understand—the various tools, songs, images, and other experiments that the music/artist/research duo have produced.

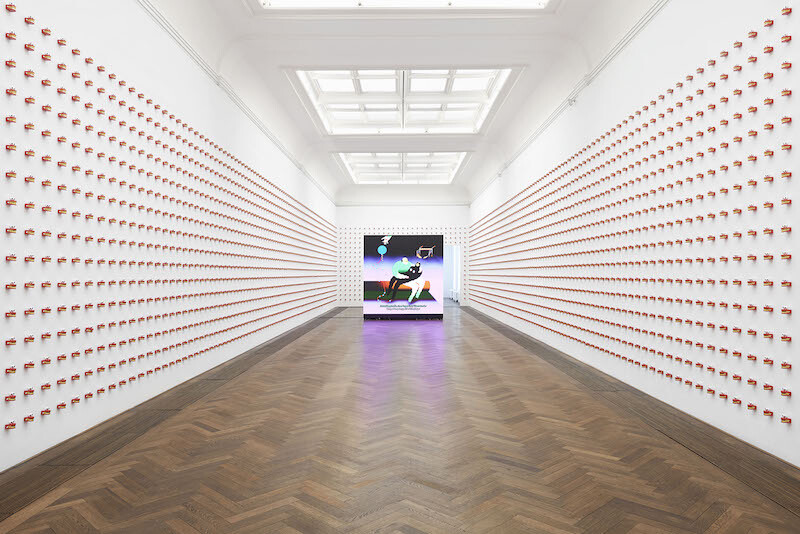

Herndon and Dryhurst are both eloquent advocates for open-minded but certainly not uncritical engagements with AI for artistic practices and, by extension, its broader sociocultural impacts. They confidently tread the (admittedly very broad) ground between AI doomers, denialists, and Big Tech-boosters, with a particular focus on the ethical use of artists’ work to produce AI models—as seen in projects such as the website Have I been Trained?, which allows artists and photographers to find out if their work has been used to train AI models. And yet, approaching “The Call,” the duo’s first solo exhibition, at London’s Serpentine Gallery, I had little sense of what “art” awaited me and, I must admit, feared diagrams of neural networks were ahead.

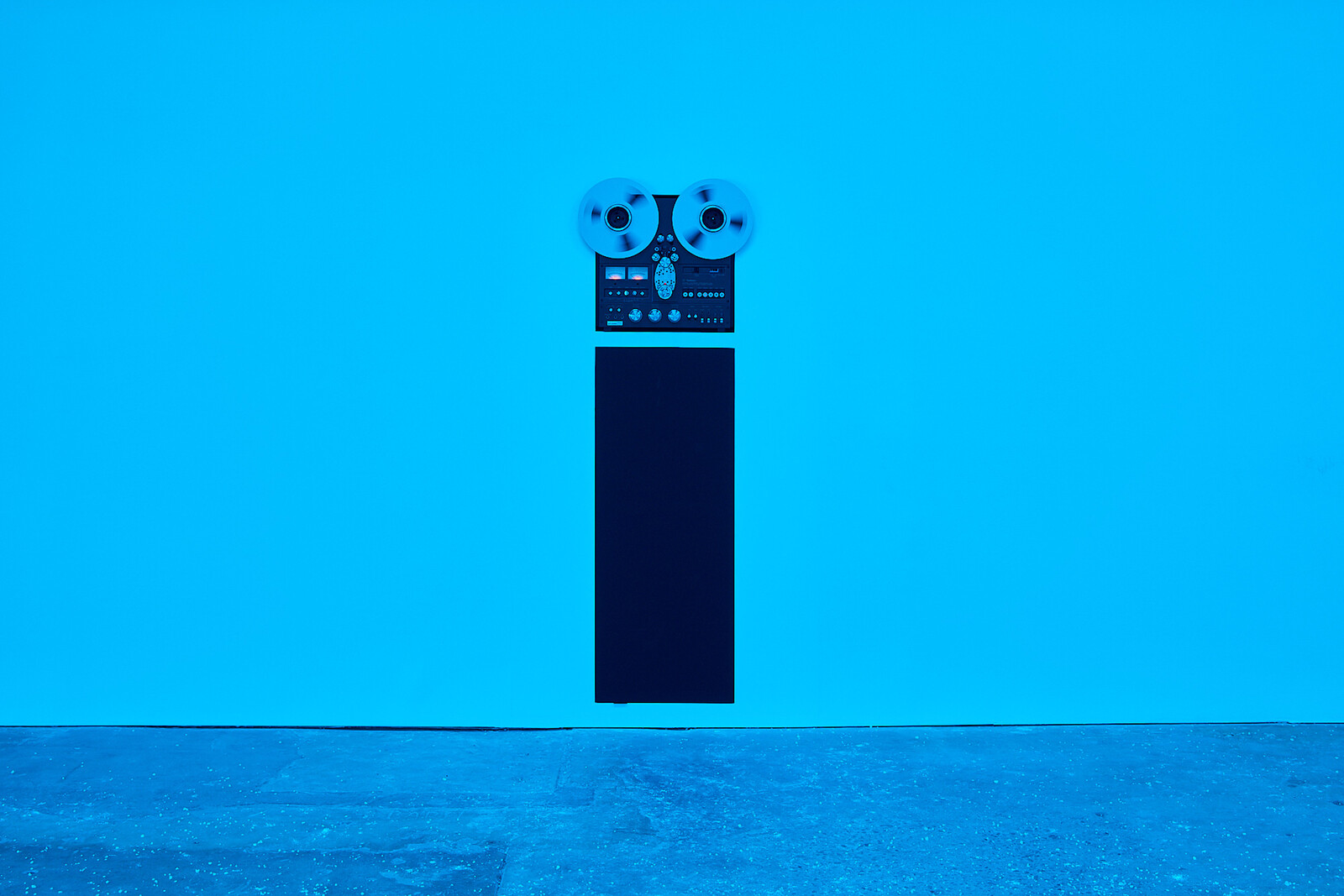

Greeting visitors to Serpentine North is The Hearth (all works 2024), a wall-mounted instrument …

November 13, 2024 – Review

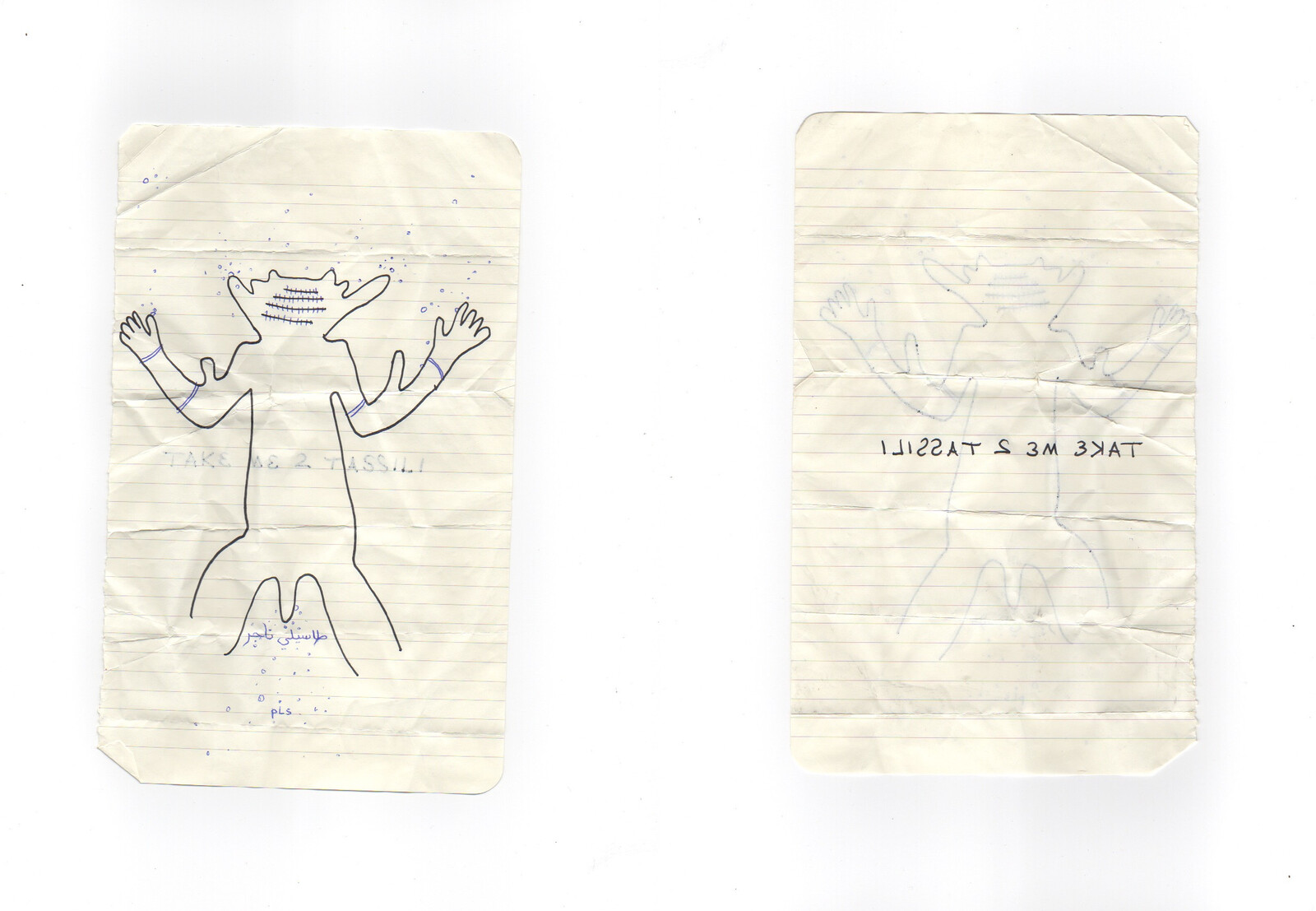

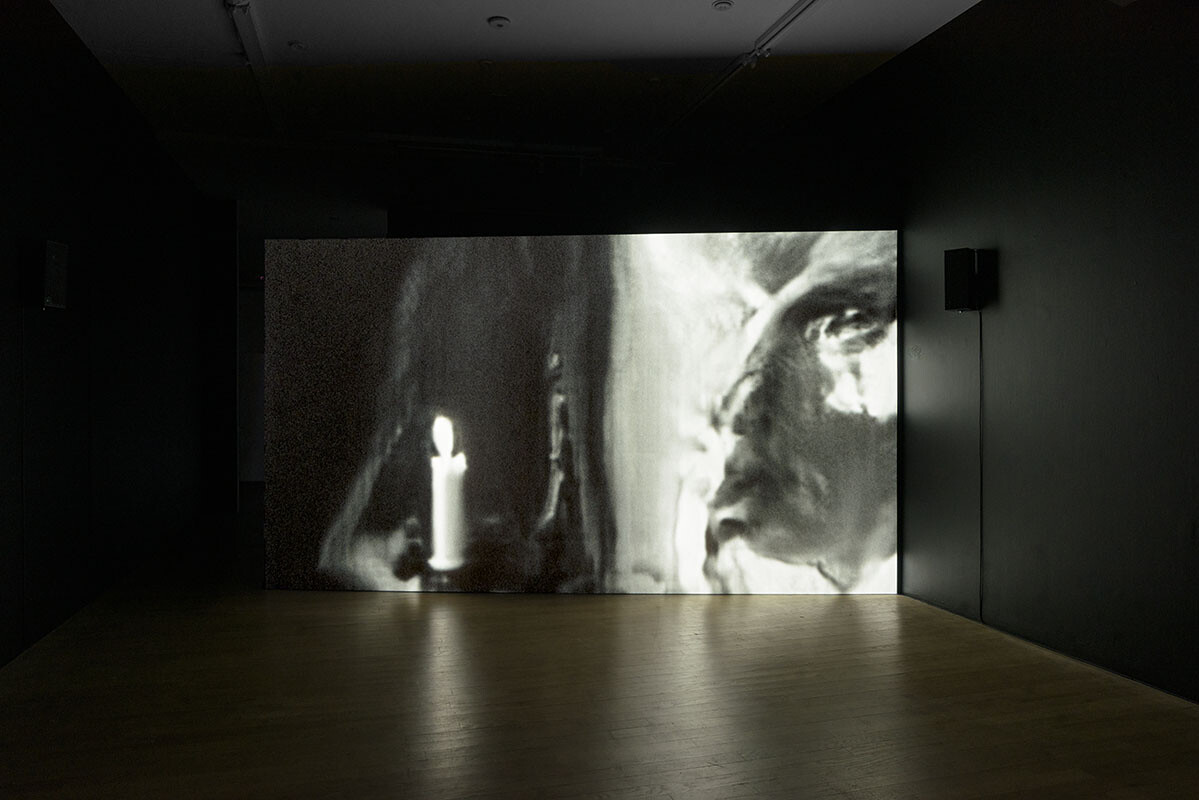

Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme’s “Until we became fire and fire us”

Oliver Basciano

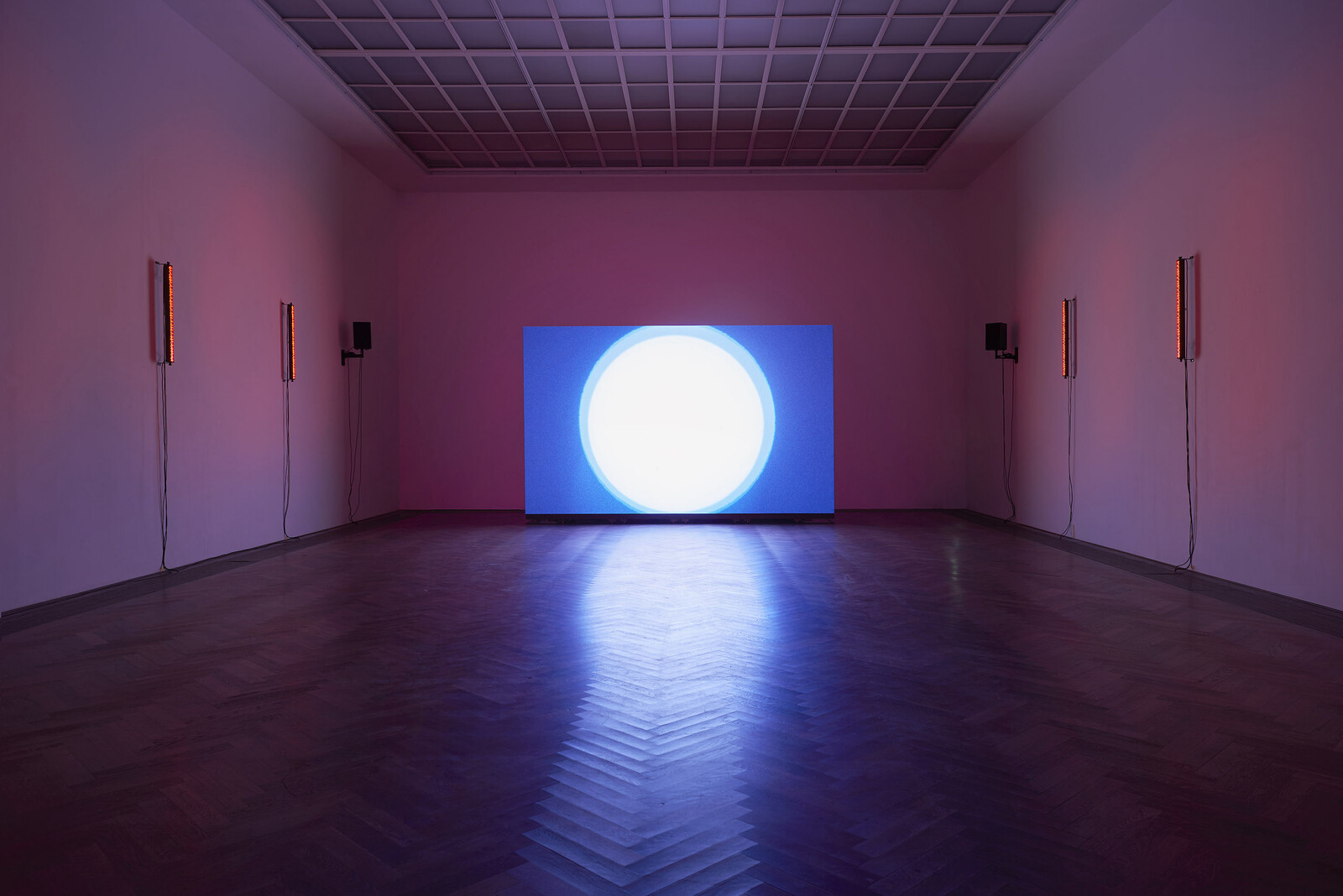

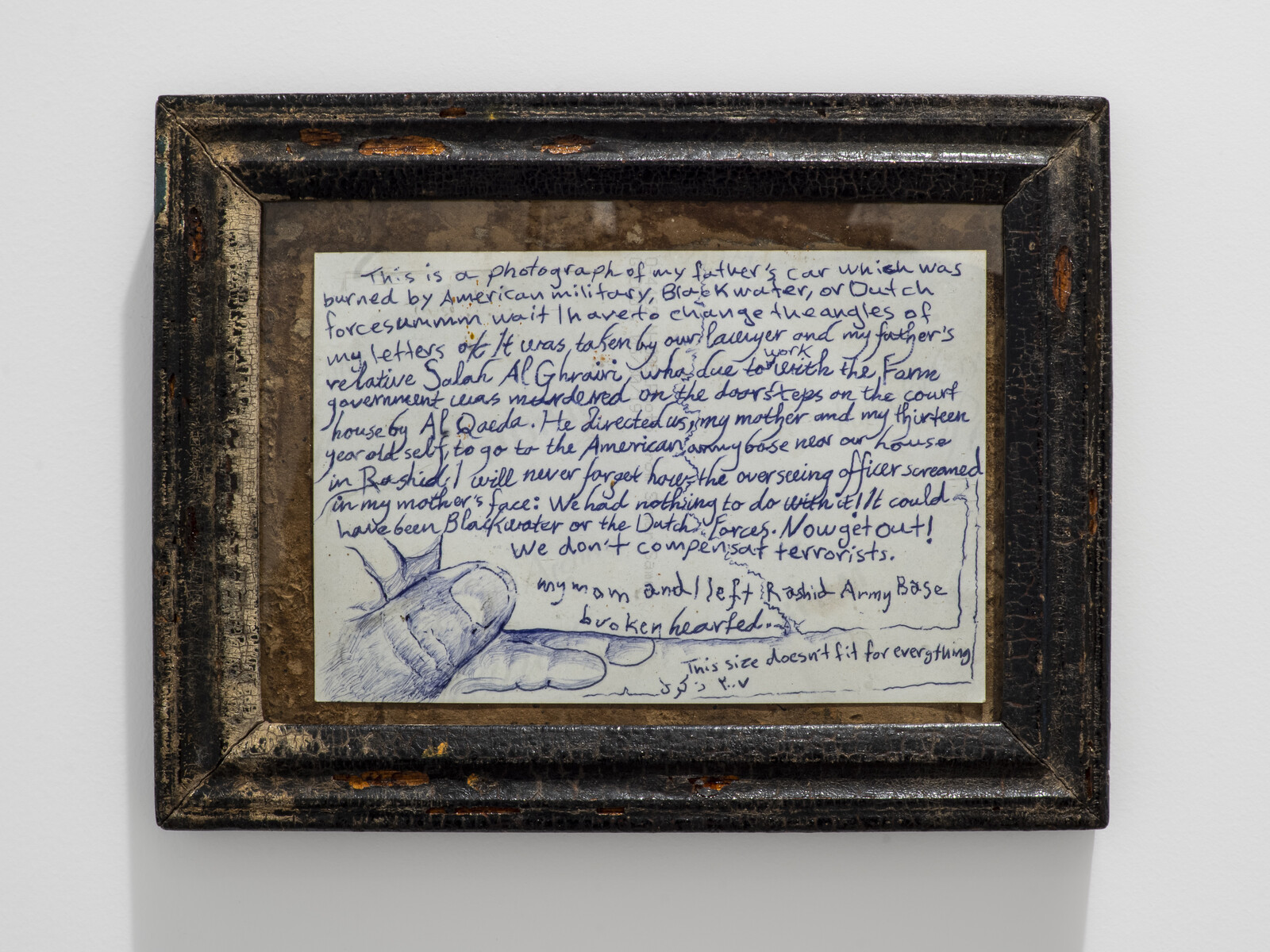

The deep boom of a subwoofer meets you on the stairs to the small gallery. Inside, a two-channel video projected across opposite walls shows barren landscapes with figures moving through them, close-ups of plants and foliage, and more besides, the imagery by turns sped up, slowed down, color-adjusted, and layered. One half is framed to the dimensions of the space; the second is projected at an angle, so the pictures invade the ceiling and floor. It is a hypnotic, unnerving assemblage.

On the gallery floor, between the two projections of Until we became fire and fire us (2023–ongoing), stand metal barricades, like sections of a security border, on which printed frames from the film are attached. Above, sheer fabric banners hang, printed from further images culled from the video. To one side, copies of a newspaper—the New York War Crimes, mimicking the design of the New York Times—are piled up on a pair of bricks and available for the visitor to take away. It tells a century-old story of Palestinian struggle and Israeli aggression through a succession of commissioned texts.

The materiality of all this stuff is in stark contrast to the subject of the thirty-two-minute, mixed-media work that lends …

November 11, 2024 – Review

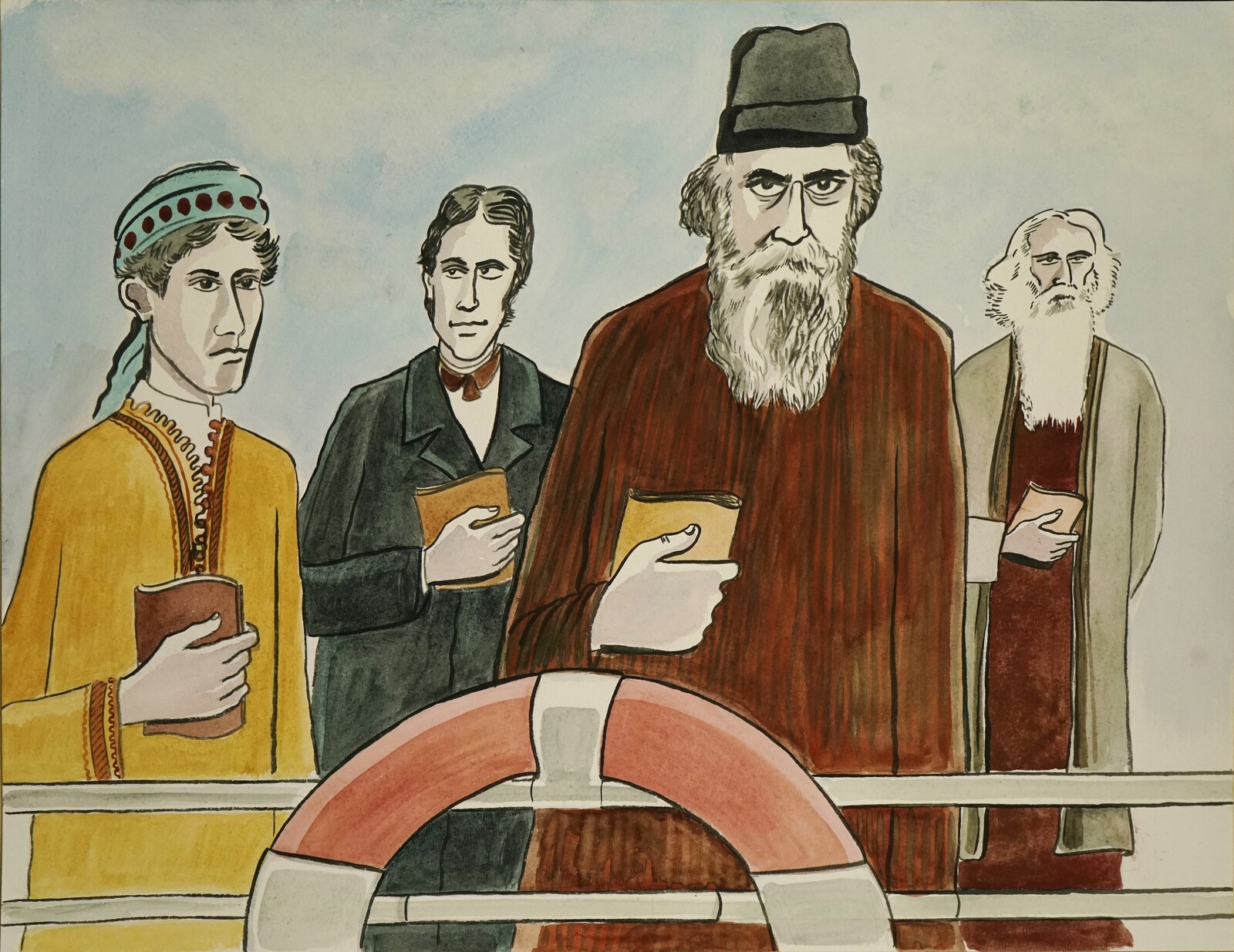

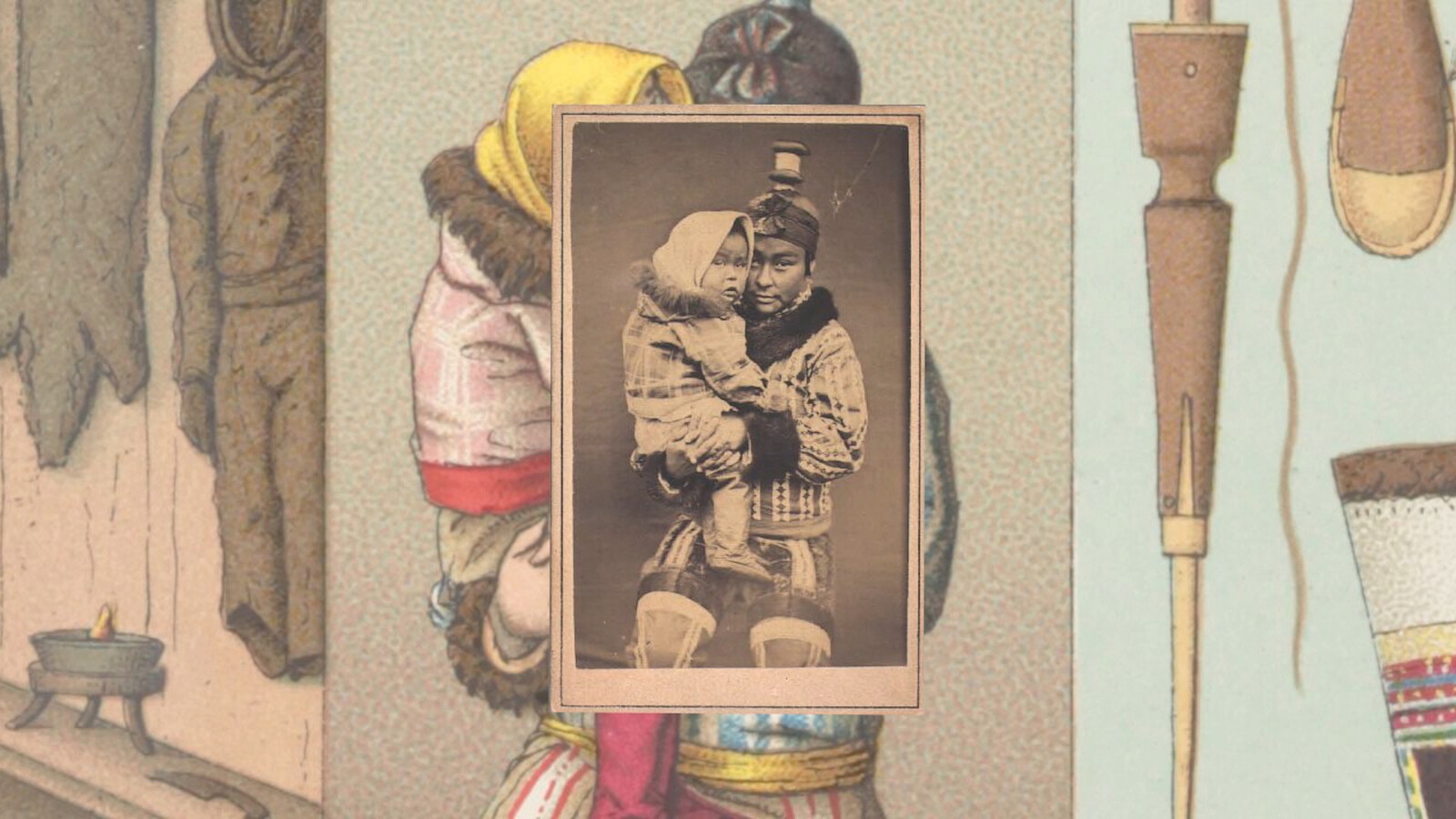

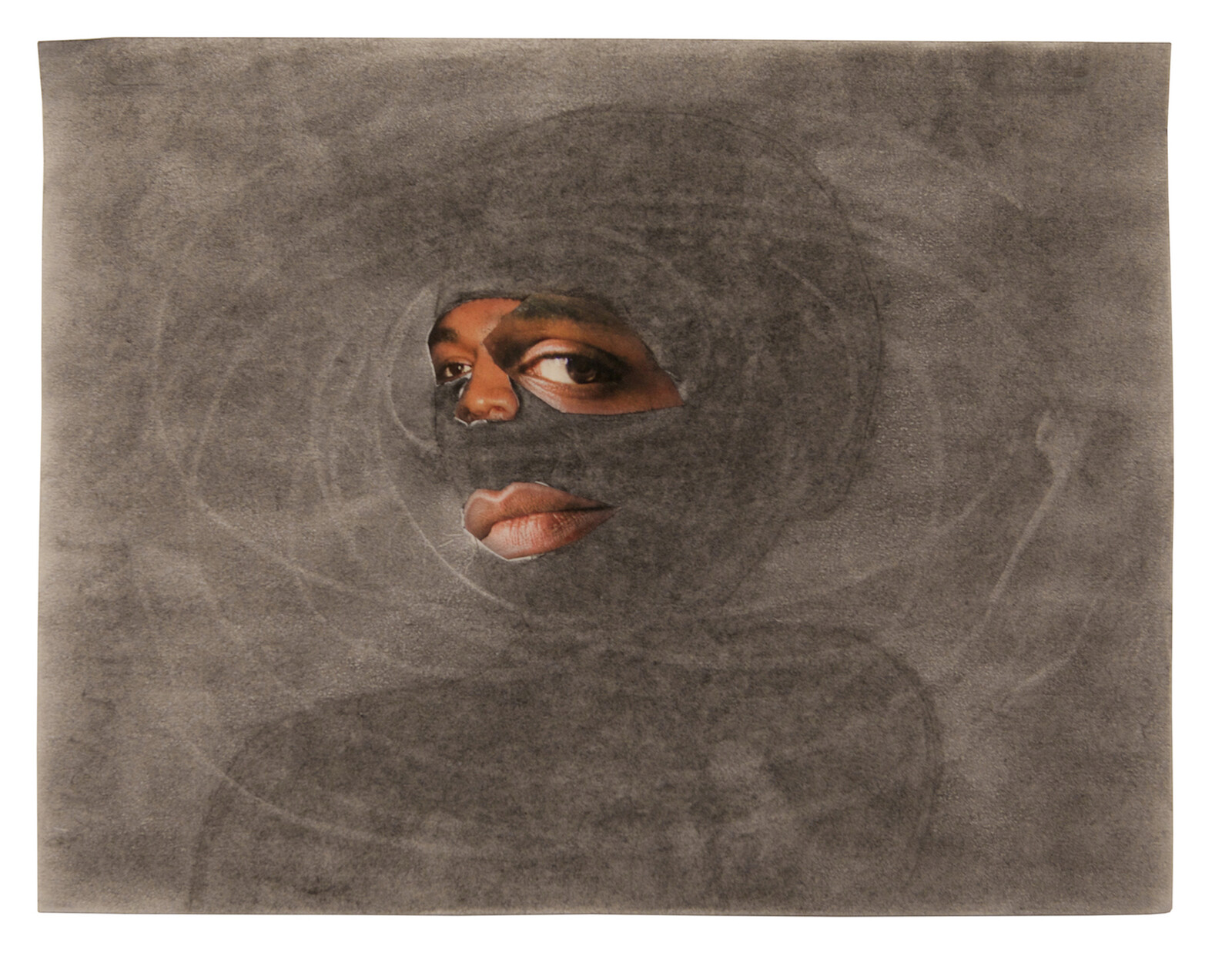

Ariella Aïsha Azoulay”s “Unshowable Photographs”

Jeremy Millar

In 2009, the curator, filmmaker, and writer on visual culture Ariella Aïsha Azoulay visited the archive of the International Committee of the Red Cross (CICR) in Geneva to look at photographs taken in Palestine during the years 1947–50. Azoulay had already worked extensively in the Israeli state archives, creating from these another archive which she called Constituent Violence 1947–1950 (first published in book form in 2009), and hoped that the photographs held by the CICR would be somewhat different from those she had, in her words, “been able to view in Zionist archives.”

These are the years of the establishing of the state of Israel, of course, and of the Nakba, or “catastrophe,” the violent displacement of approximately half the Arab population in Palestine—around 750,000 people. While the CICR had been present “at places in Palestine where massacre, expulsion, and destruction had taken place,” they had relatively few photographs, and most of these were not taken during the Nakba. Indeed, many of them were similar, though not identical, to those seen by Azoulay in Israeli archives—the same people, the same place, the same ongoing event, but just shown from a slightly different angle, a slightly different point of view.

But …

November 8, 2024 – Feature

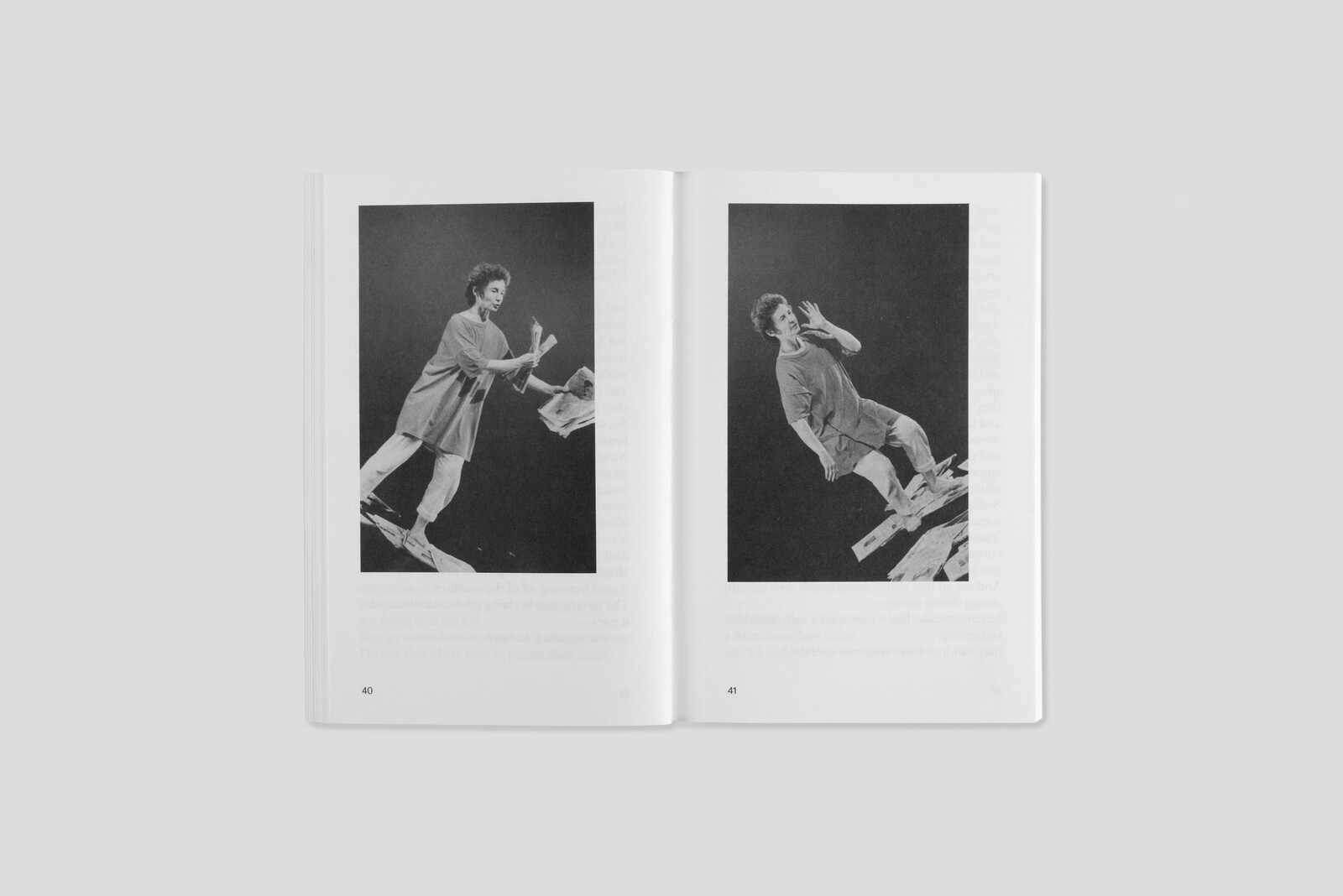

Hervé Guibert’s Suzanne and Louise

John Douglas Millar

There is a line of criticism that argues that Karl Marx’s Das Kapital (1867–94) is the great gothic novel of the nineteenth century. It’s a line that runs through an essay by the poet Keston Sutherland that, in a bravura piece of close reading, explores the stakes involved in the translation into English of the German word Gallerte. When Marx writes about “bloße Gallerte unterschiedsloser menschlicher Arbeit,” Sutherland argues, he does not refer only to “congealed quantities of human labor,” as the line is most often rendered in English.

He is in fact referring to a staple of German foods and cosmetics; gallerte, Sutherland explains, “was made from the off-cuts and the discarded bits of animals from early industrial slaughter processes. It was the stuff the bourgeoisie wouldn’t want to eat in its natural form, but which could be boiled down and turned into this great mush and then used in breakfast condiments or cosmetics.”

Marx wants the reader to feel the full brutality of what capitalism does to laboring bodies. He wants to reveal the horror beneath the social codes by which the bourgeois protect themselves from the gory facts of the capitalist mode of production sustaining their existence. …

November 7, 2024 – Review

“Meditation Room: Sacred Spaces Program”

Natasha Marie Llorens

The tiled floor of Konsthall C has seen hard use, both in the twenty years it has functioned as an experimental art space and, before that, as the common laundry room for the rental apartments in this suburb of Stockholm. Time and traffic have eroded the diagonal pattern of beige and dark-gray squares, and now the floor looks clean and utilitarian. This kind of straightforward durability is the appropriately mundane ground for the inaugural exhibition of Mariam Elnozahy’s first program as Konsthall C’s artistic director. Her two-year thematic proposition “Sacred Spaces” is balanced between a positivist understanding of the sacred as someplace metaphysically safe and an idea that the contemporary art institution might offer “a place to discuss religious pluralism.” The intervention arises in a febrile context: a long-running debate in Swedish courts over whether burning the Koran could be seen as a form of political protest; an extreme rise in gang-related gun violence—Sweden is now second only to Albania in Europe—with attendant media coverage often emphasizing immigration and ethnic identity, with overtones of politico-religious affiliation.

It would have been easy to open a program along these thematic lines with something confrontational, but instead Elnozahy reproduced, inside the gallery, the …

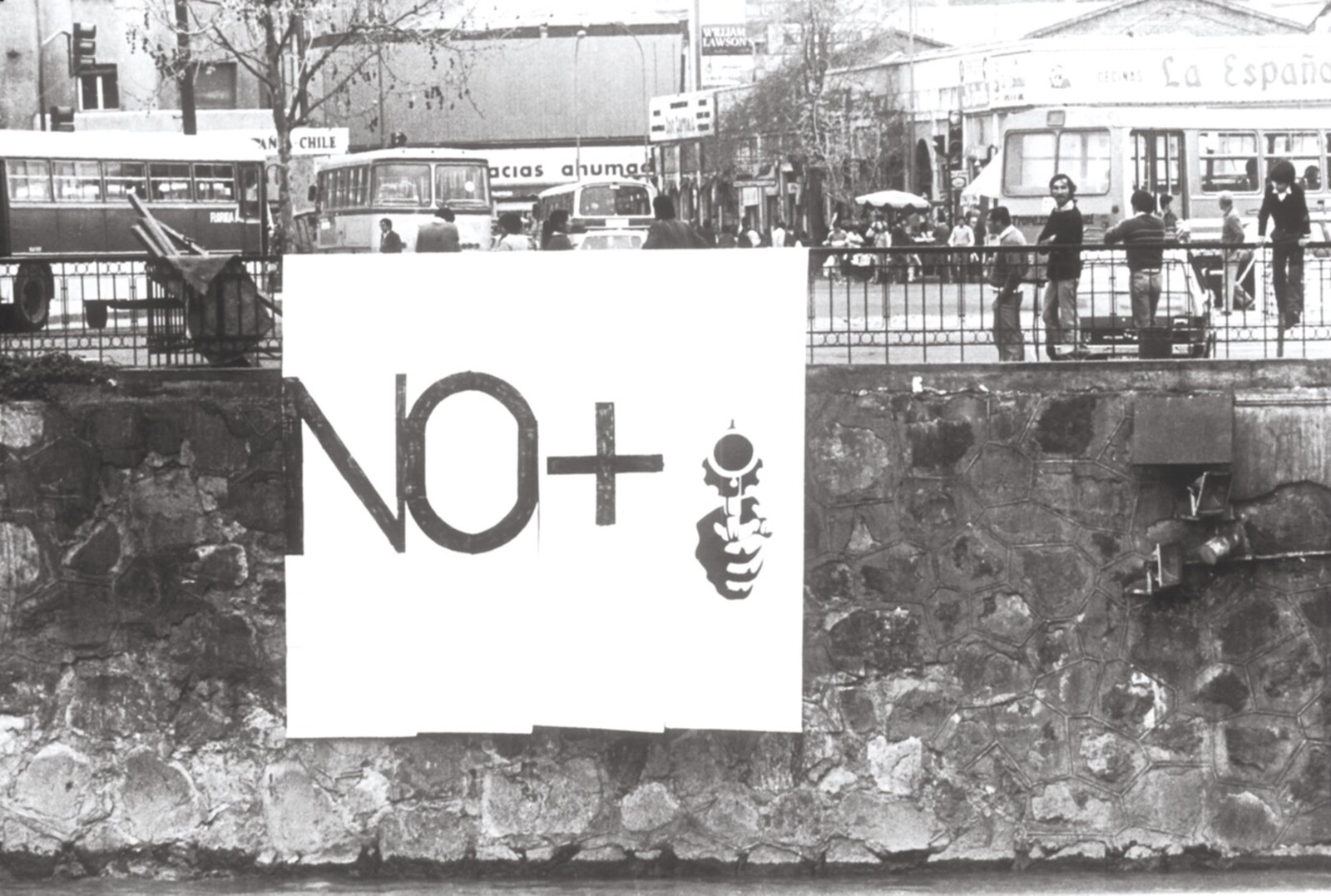

November 5, 2024 – Editorial

Stages

The Editors

Sometimes it is better to let the work speak to the moment. We begin this month with a text reflecting on a recreation of the “meditation room” installed at the UN headquarters by a diplomat later rumored to have been murdered for his commitment to the organization’s ideals. While we must acknowledge that even spaces of spiritual experience are implicated in structures of power, writes Natasha Marie Llorens, this work suggests that “the most violent stages” can nonetheless “be instrumentalized in service to subtle and multivalent forms of resistance.” We can only hope.

It is the nature of art that the work (and its criticism) will always be inflected by those events by which it—and we—are surrounded. That is especially the case when those events are as consuming of our attention as the US election or Israel’s increasingly unconstrained destruction of Gaza. An exhibition of Ariella Aïsha Azoulay’s “Unshowable Photographs” also illustrates how works of art can slip the purposes to which they are put by transforming photographs whose meanings have literally been fixed into drawings that might speak for themselves. That there are no illusions here about the function of images is not a cause for despair so much …

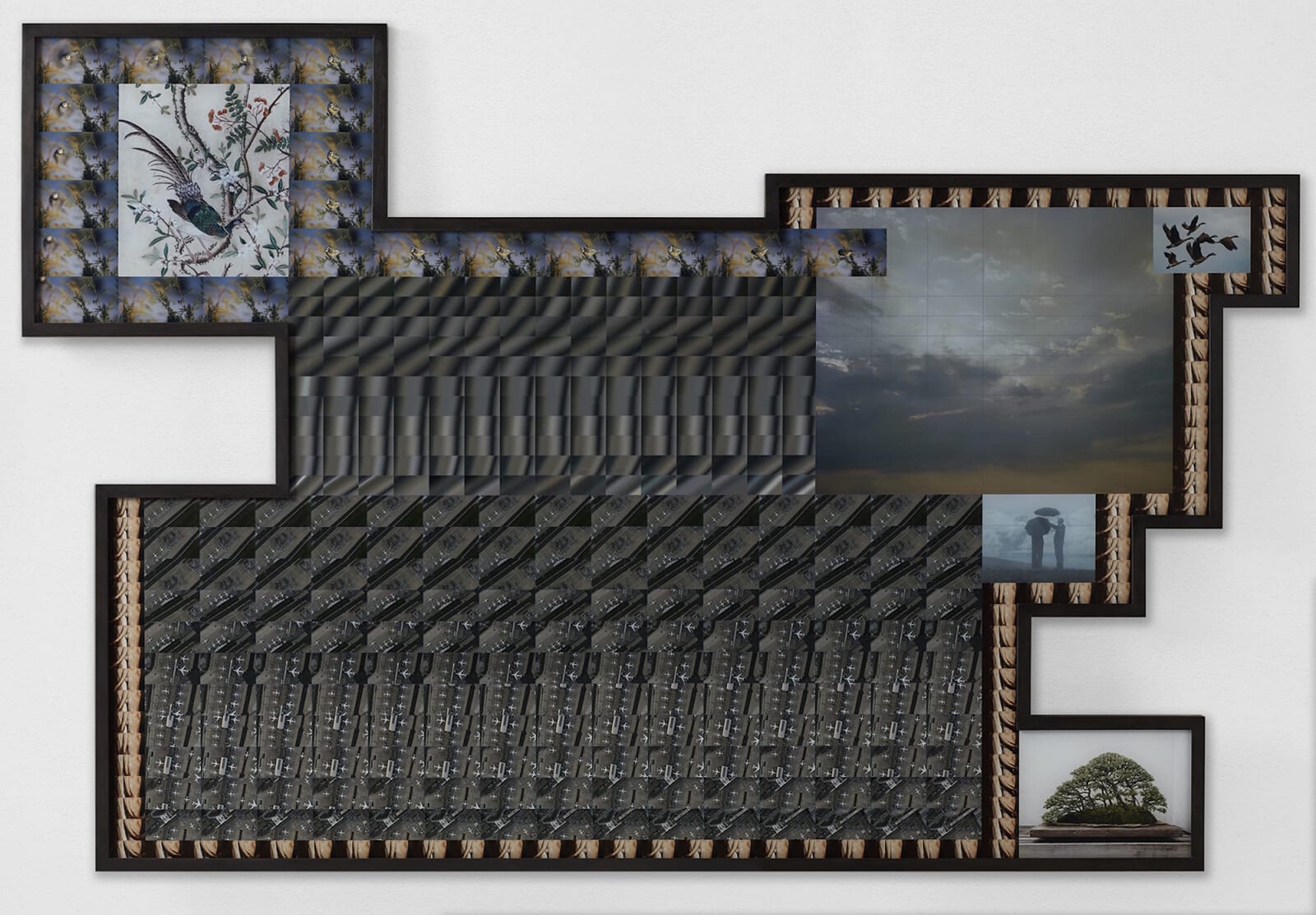

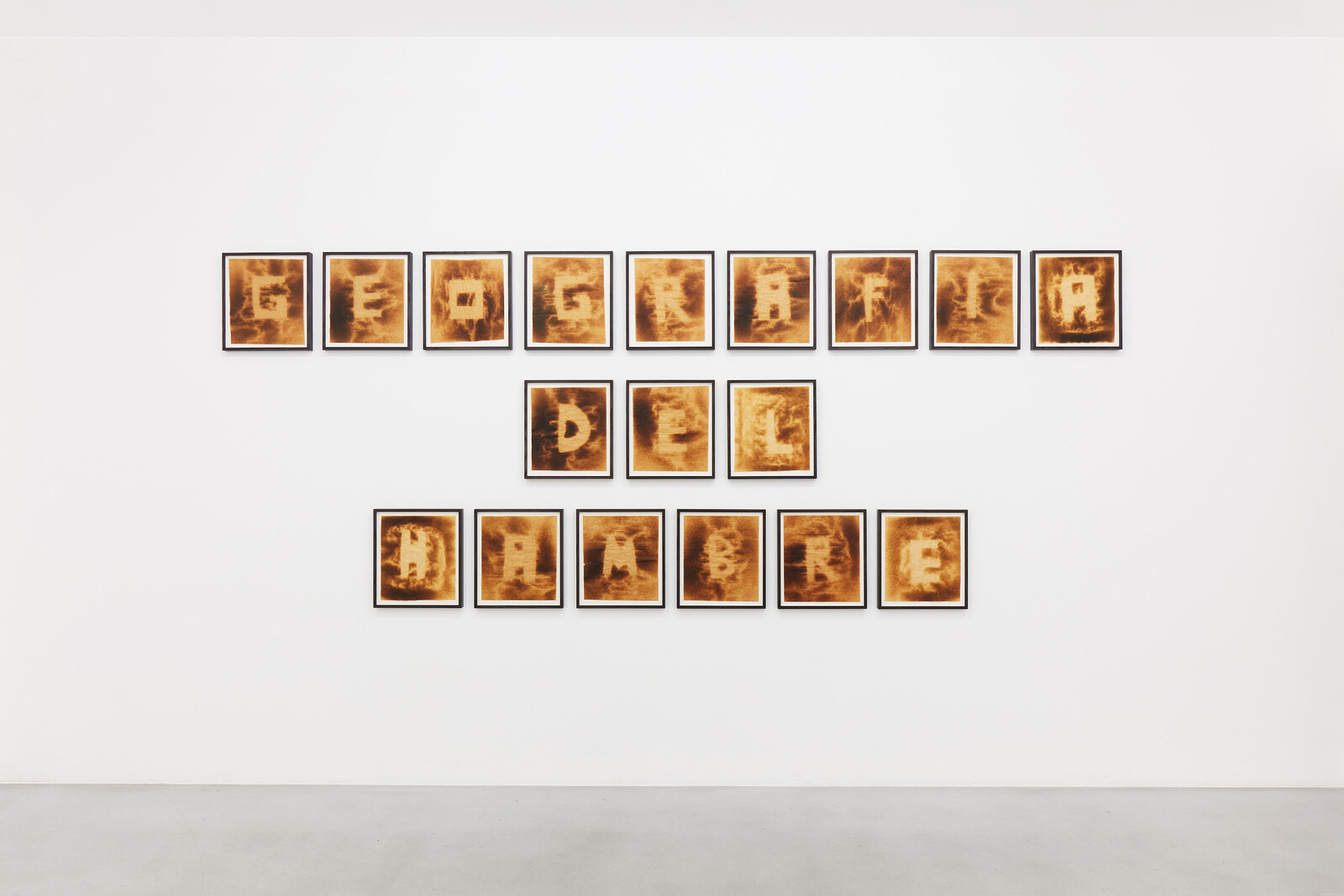

November 4, 2024 – Review

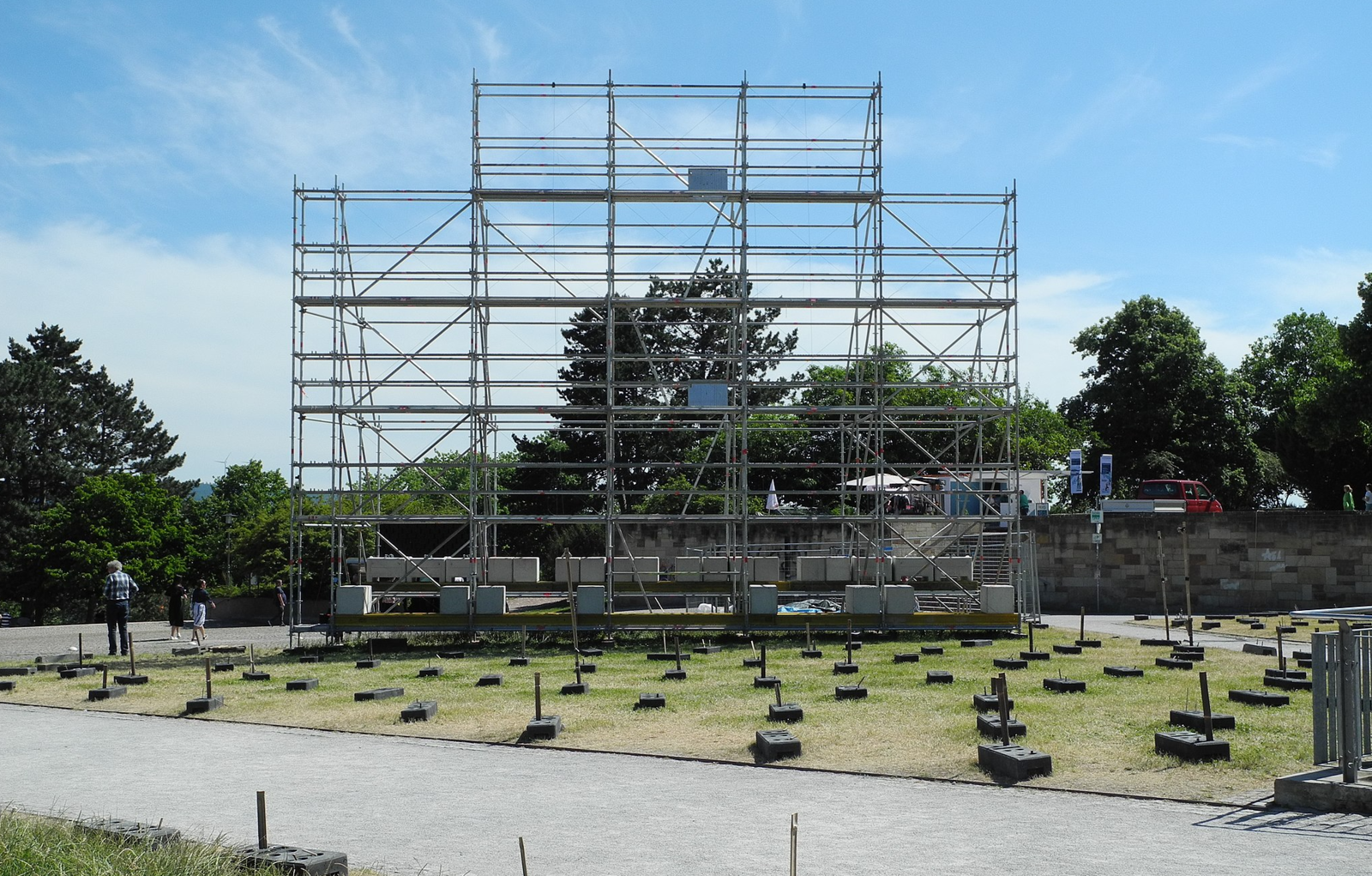

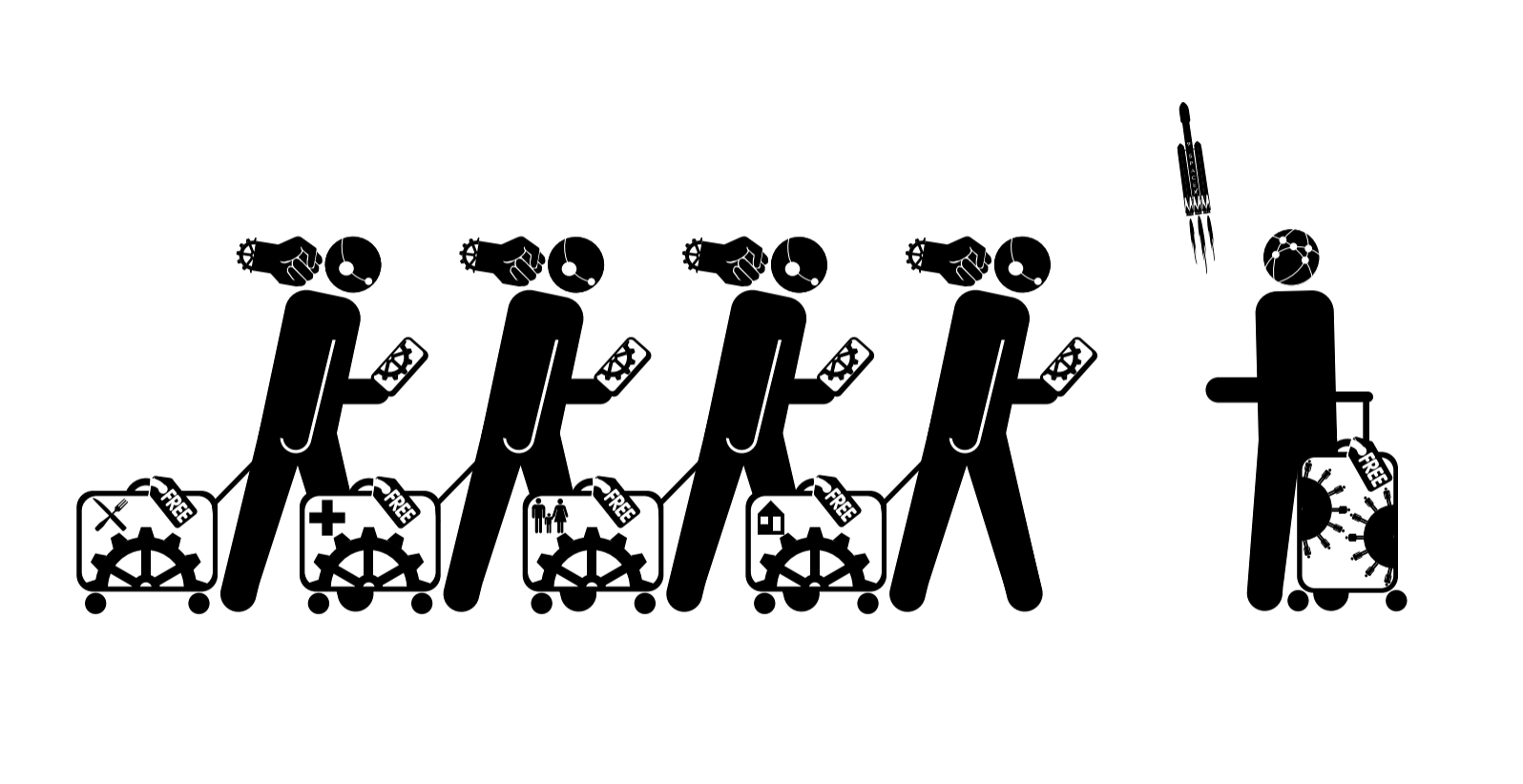

“Made in Germany? Art and Identity in a Global Nation”

Luise Mörke

On the Harvard campus, relics of Germanic high culture are never far away: a bronze replica of a medieval lion sculpture from Lower Saxony graces the courtyard of Adolphus Busch Hall, named for an émigré who made his fortune selling—what else?—beer and diesel engines. A counterpoint to that building’s historicist opulence can be found in the sober Modernism of the Law School’s graduate dorms designed by a team led by Walter Gropius during his tenure at the university. As ciphers for rigor, perfection, and intellectual prowess, mythical versions of Germany are deployed as fodder for the Harvard myth itself.

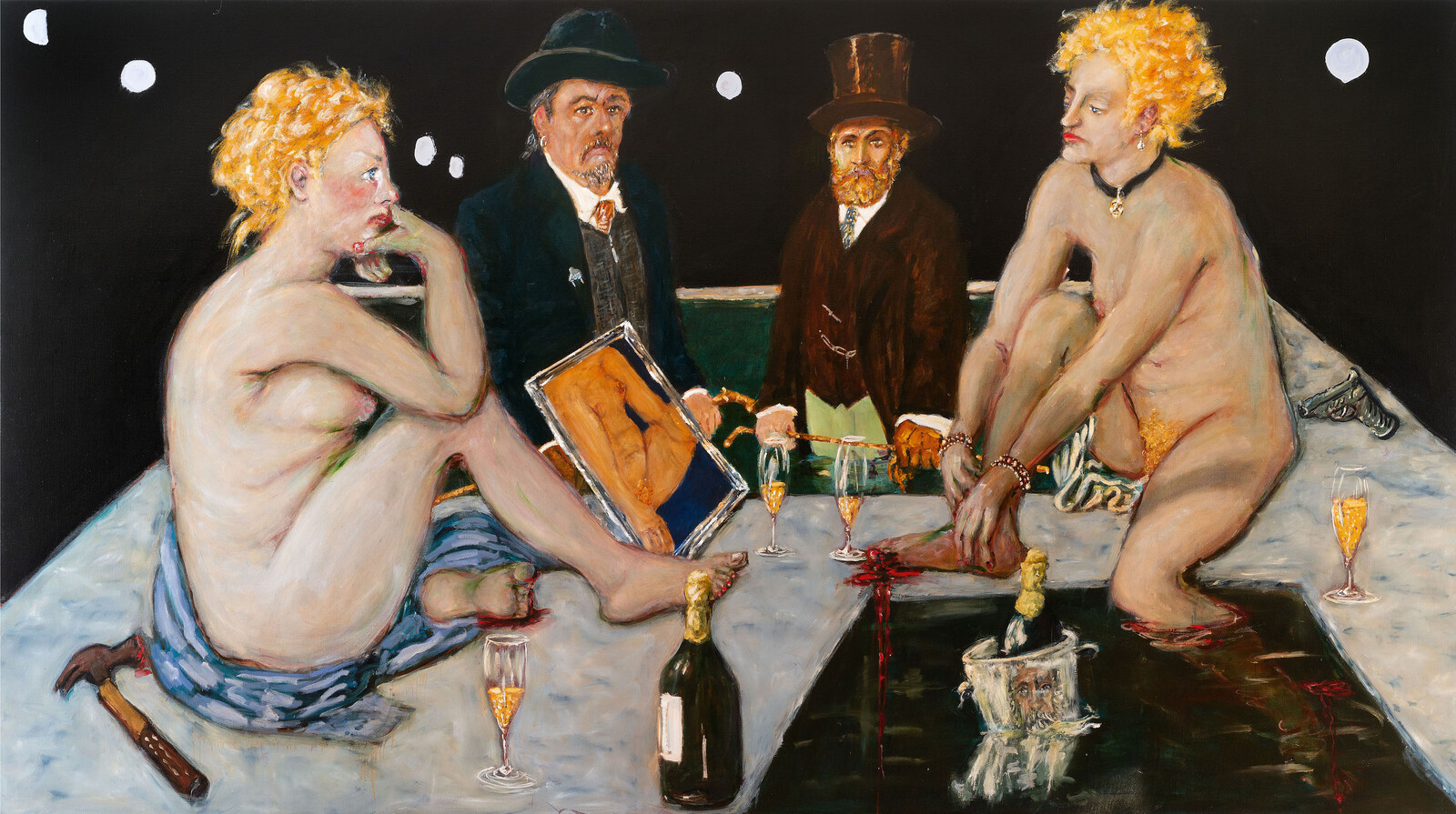

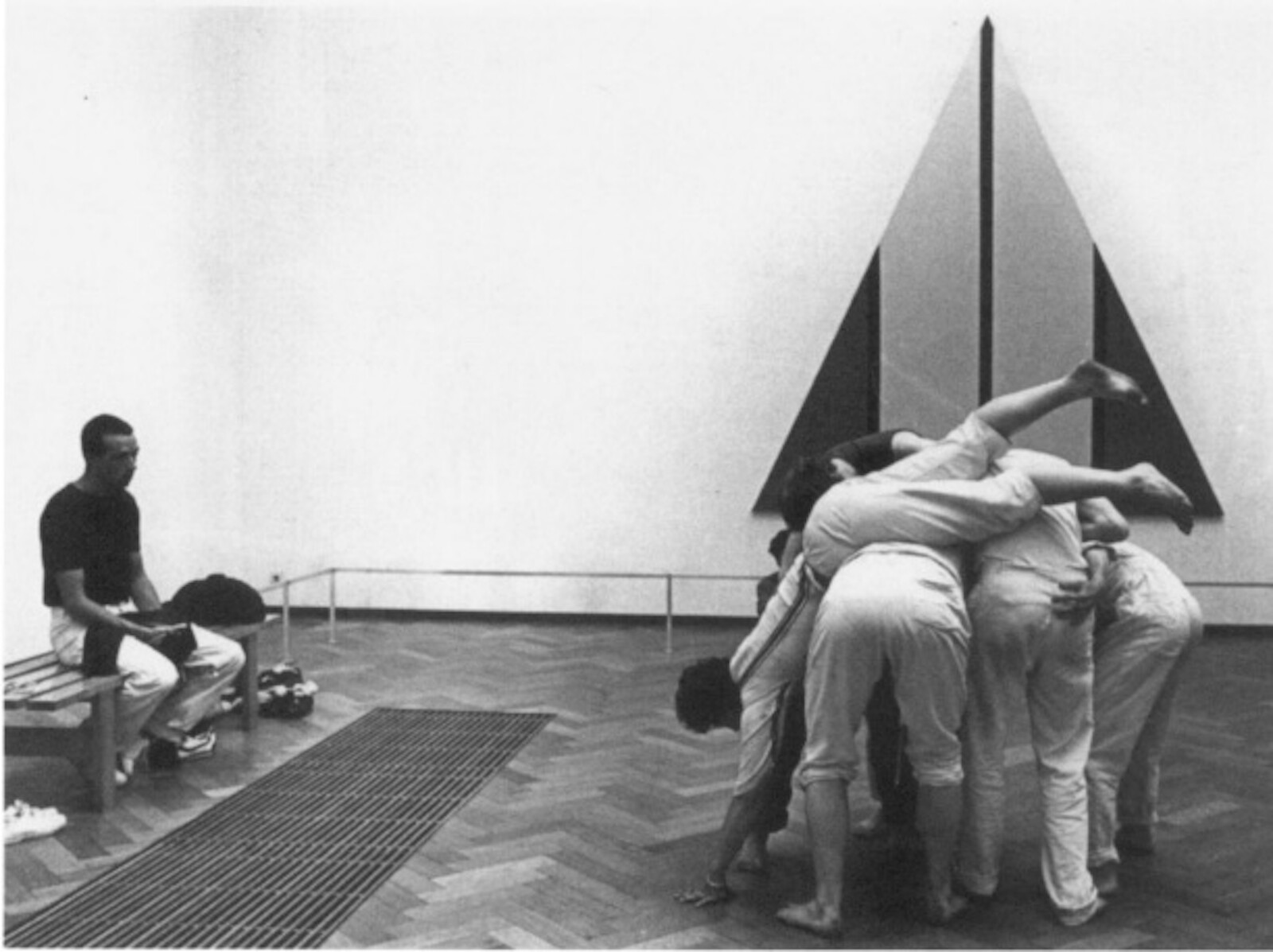

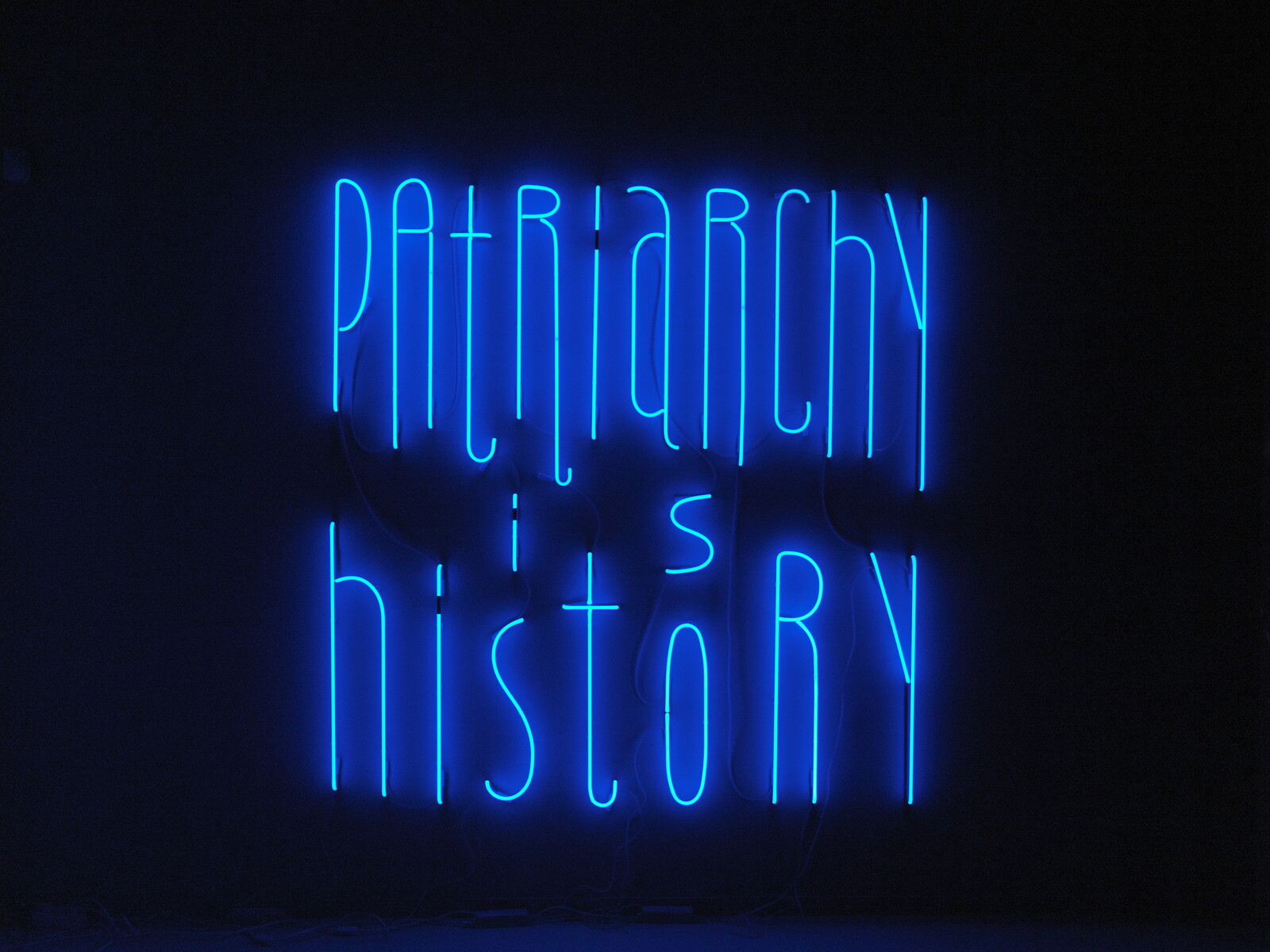

“Made in Germany? Art and Identity in a Global Nation,” at the university’s Busch-Reisinger Museum, adds a further chapter to this transatlantic double vision, focusing on art since 1980 from the GDR and the Federal Republic (FRG). However, national myth-making here gives way to an astute selection of artworks that pry open the cracks in a state that defines belonging foremost through adherence to cultural and linguistic standards, evident in the language and knowledge test that immigrants must pass for naturalization. “Made in Germany?” coaxes out the tense dialectics between a nation’s openness towards outside cultures and economies, and the nationalist …

October 30, 2024 – Review

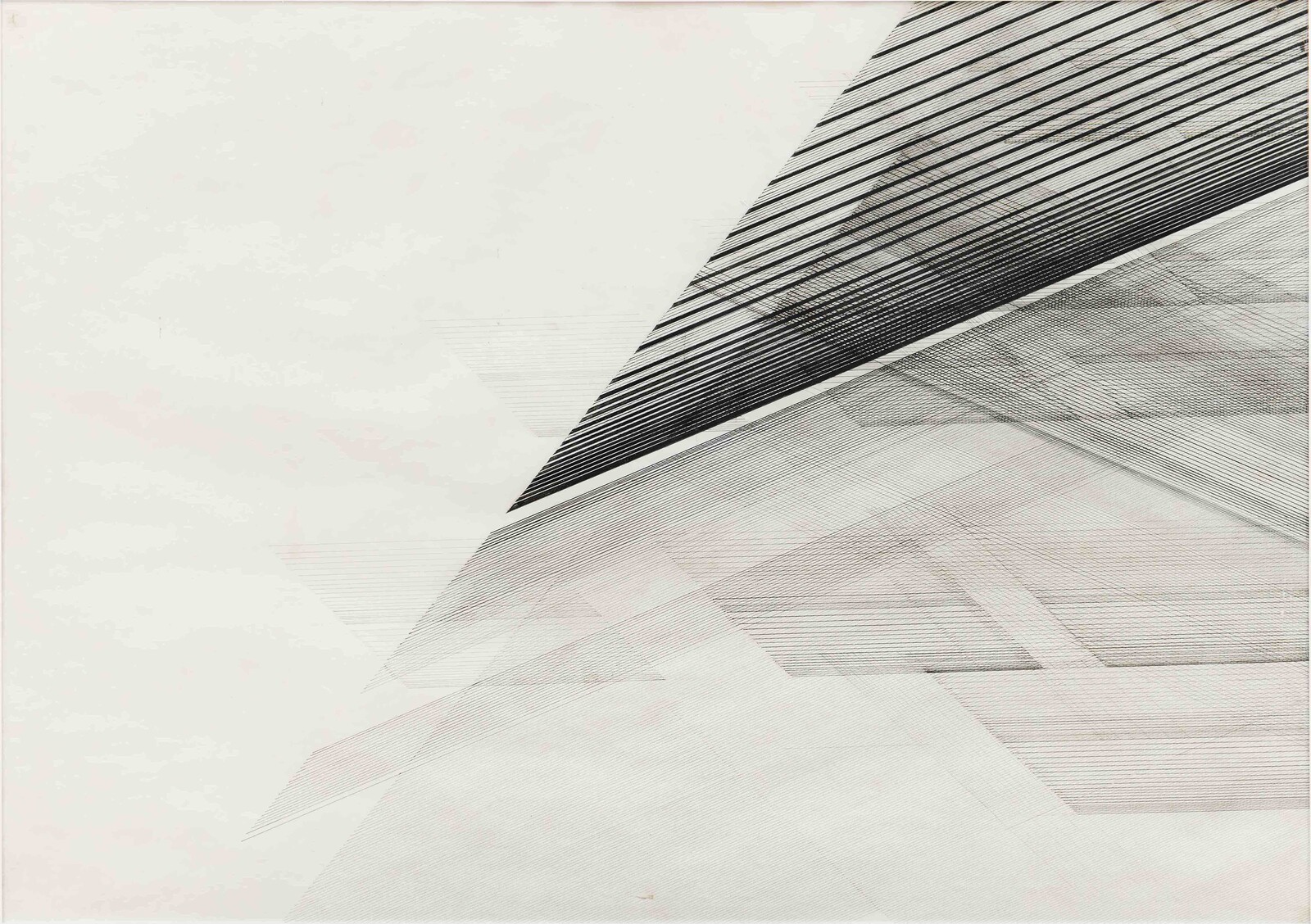

Kim Lim’s “The Space Between. A Retrospective”

Adeline Chia

Kim Lim’s dark wood sculpture Pegasus (1962) is an earthbound, stiff-backed version of the mythical flying horse. Shaped like a totem, it has no discernible head or legs, only a central column to which two slim semi-circular pieces of wood (the “wings”) are hinged. Pegasus, steed of the muses and symbol of the unbridled imagination, is portrayed here with a certain restraint. In fact, the sculpture reminds me of a practitioner of another disciplined art—a straight-backed ballerina moving between first and second positions, arms opening and closing gracefully.

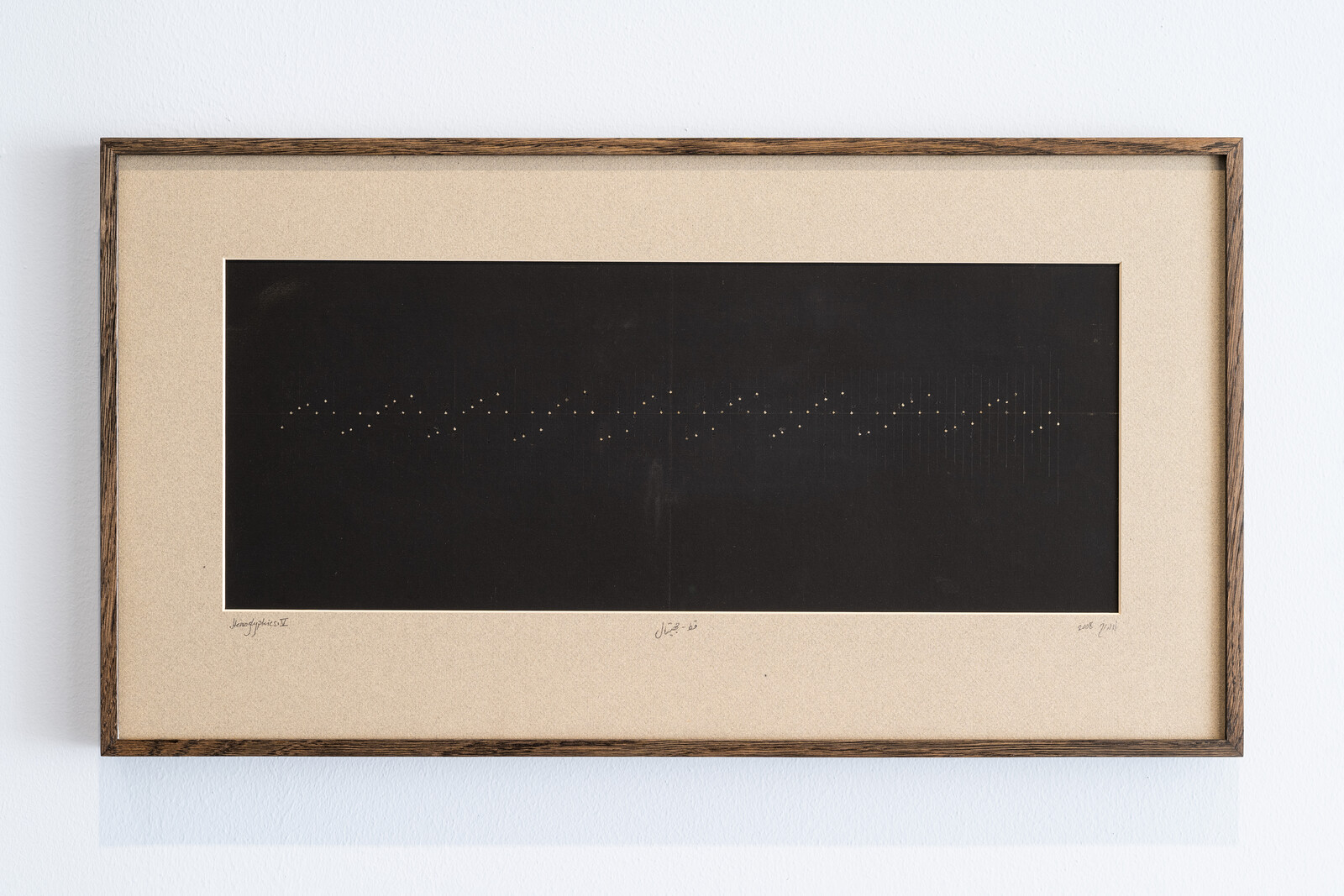

Subtlety and economy define Kim Lim’s practice, which includes abstract wooden and stone-carved sculptures, often inspired by nature, as well as prints that were developed in tandem. Only in the past two decades has Lim received attention in her two home contexts: Singapore, where she was born in 1936, and England, where she attended art school, started a family, and lived until her death from cancer at the age of sixty-one. Major shows at Tate Britain and Hepworth Wakefield have situated her in British postwar art history alongside Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, and Lim’s husband William Turnbull. The Singapore Tyler Print Institute staged a retrospective of her prints in 2018, establishing her …

October 28, 2024 – Review

Diego Marcon’s “La Gola”

Michael Kurtz

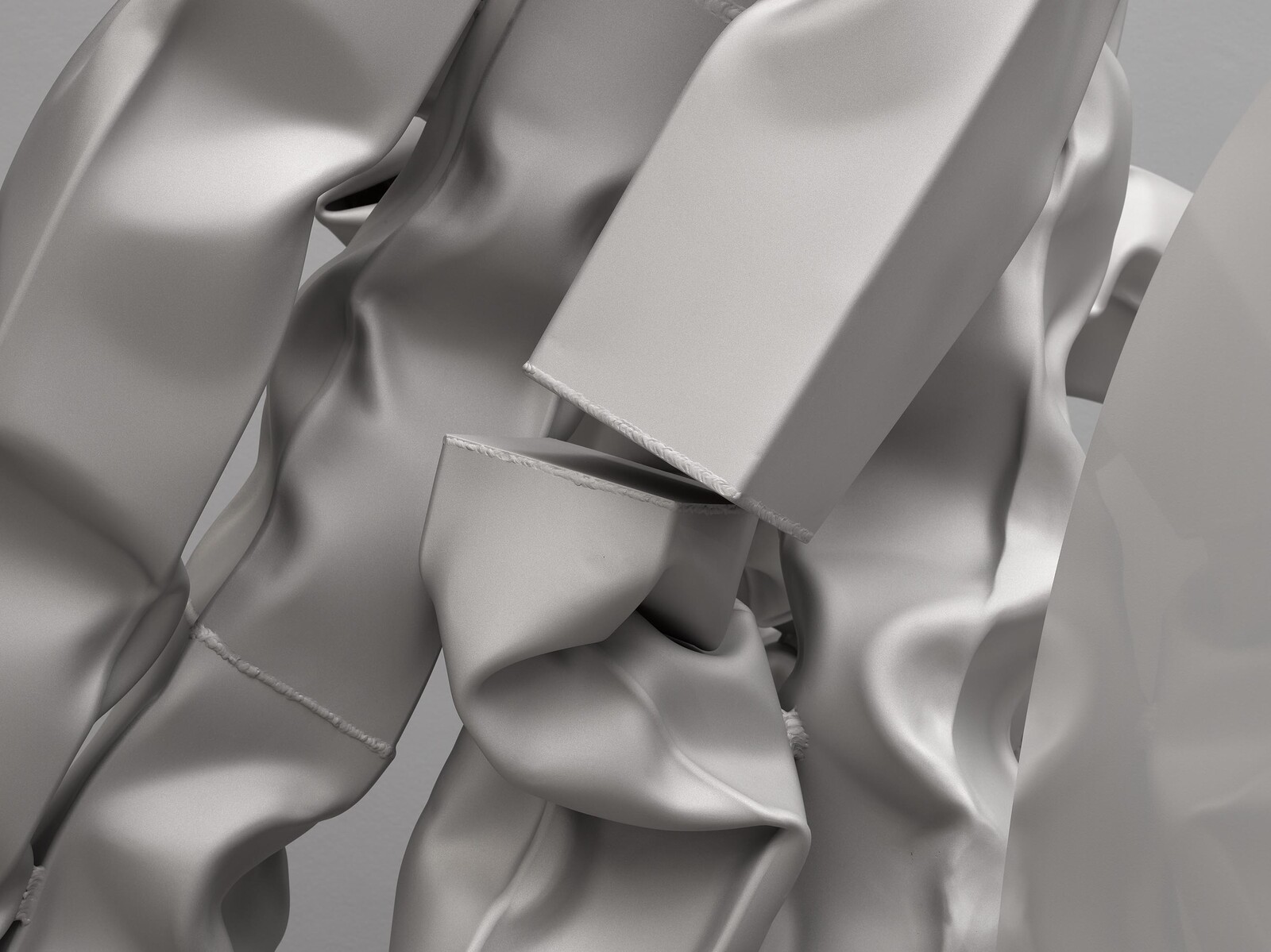

Diego Marcon’s short films pair idiosyncratic approaches to animation with painful and provocative subject matter. In Monelle (2017) sleeping girls are tormented by ghoulish CGI figures amid the darkness of the old Fascist headquarters in Como. In The Parents’ Room (2021), a father, played by an actor wearing an emotionless mask, performs an opera about how he murdered his family. And in Fritz (2024) a computer-animated boy hangs from a noose, half-dead but still yodelling.

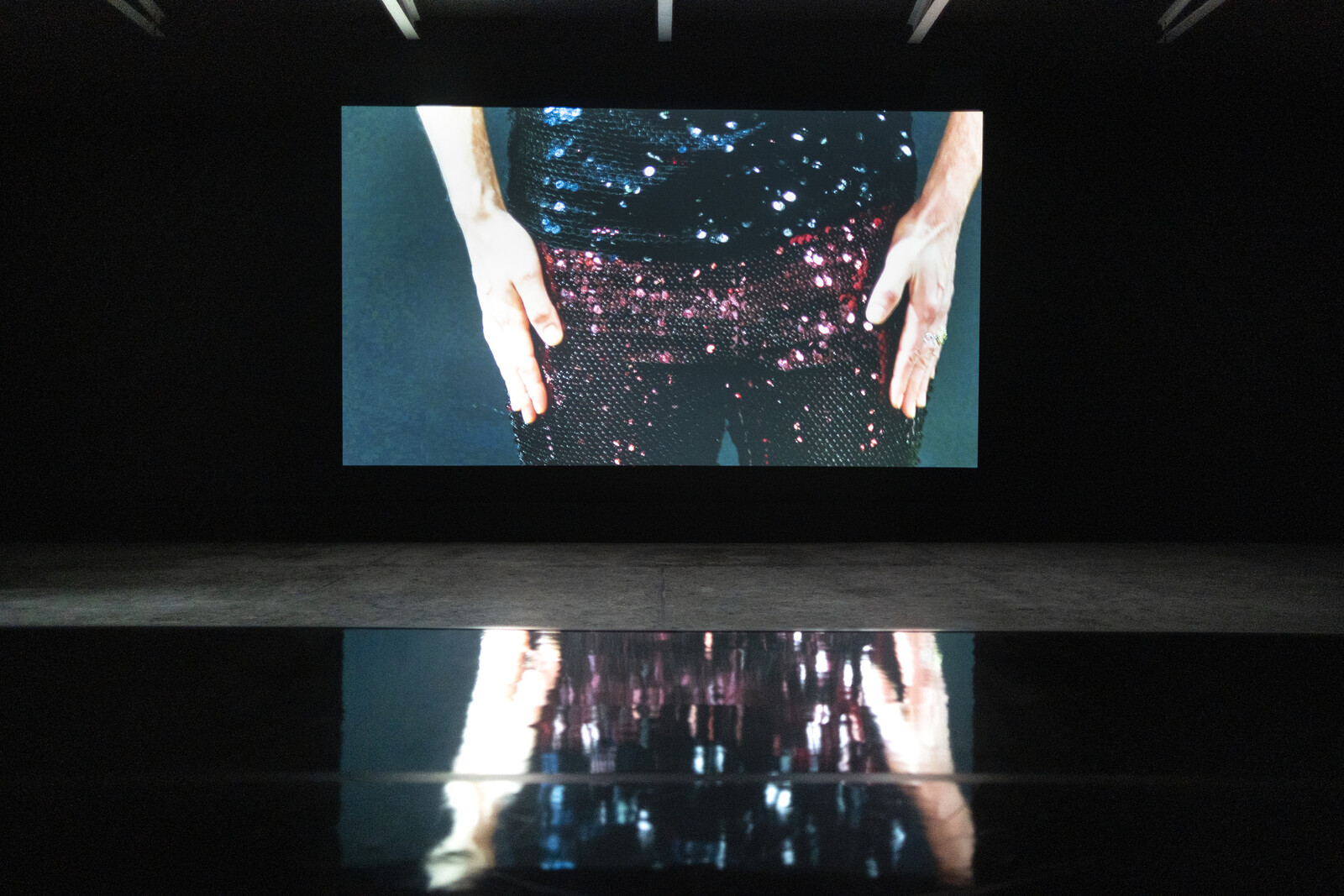

His new film, La Gola (2024), dramatizes an epistolary exchange between Gianni and Rossana, who are represented by hyper-realistic mannequins. The two characters appear in a series of close-ups, every time in a new outfit and location, as their letters are read in a voiceover backed by organ music. Gianni recounts the details of a recent feast, from a medieval soup served in an eggshell to Torta Fedora, a Sicilian cake covered in “mischievous ruffles” of “whipped ricotta,” which he calls “the bakeable Baroque!” Meanwhile, Rossana sends updates on her mother’s declining health, reporting an assortment of gruesome ailments including “flaccid little blisters” that ooze “syrupy fluid” and “diarrhoea accompanied by mucus.”

In this caricature of traditional gender dynamics, he indulges in unchecked consumption while …

October 25, 2024 – Feature

Warsaw Roundup

Ewa Borysiewicz

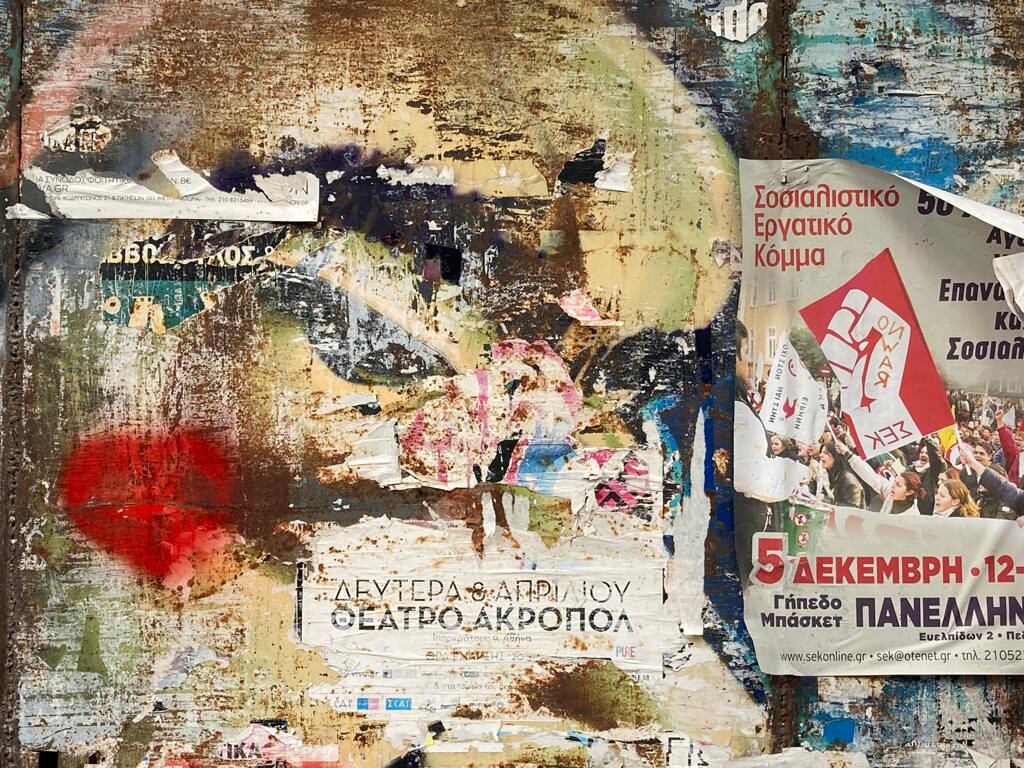

Eight years of government by the right-wing Law and Justice party, which came to an end a year ago, severely damaged Poland’s cultural sector, not least by undermining the credibility of the capital’s art institutions. In these circumstances, the responsibility of safekeeping Warsaw’s reputation as a regional hub for contemporary art fell to its commercial galleries. In spite—or perhaps because of—the political and economic climate, recent years have also seen a growing number of non-commercial and artist-led initiatives in Warsaw, gathered together by the annual FRINGE Warszawa. Coordinated by members of the independent art community, its third edition platformed more than eighty spaces, complementing the more than 100 openings taking place as part of the simultaneous gallery weekend.

In contrast to the gallery weekend, the venues of which are concentrated around the city center, FRINGE sprawled across Warsaw. Visitors were invited to scout the Vistula riverbank for Karolina Majewska’s “Holy Trees” (2021–ongoing), a series of beeswax body parts attached to tree trunks, and venture to the Kowalscy confectionery, where Kacper Tomaszewski and Mateusz Włodarek’s exhibition “Through the Stomach to the Heart” celebrated friendship and sweets. The curators playfully paired the works with offerings from the city’s traditional pastry shop, giving …

October 24, 2024 – Review

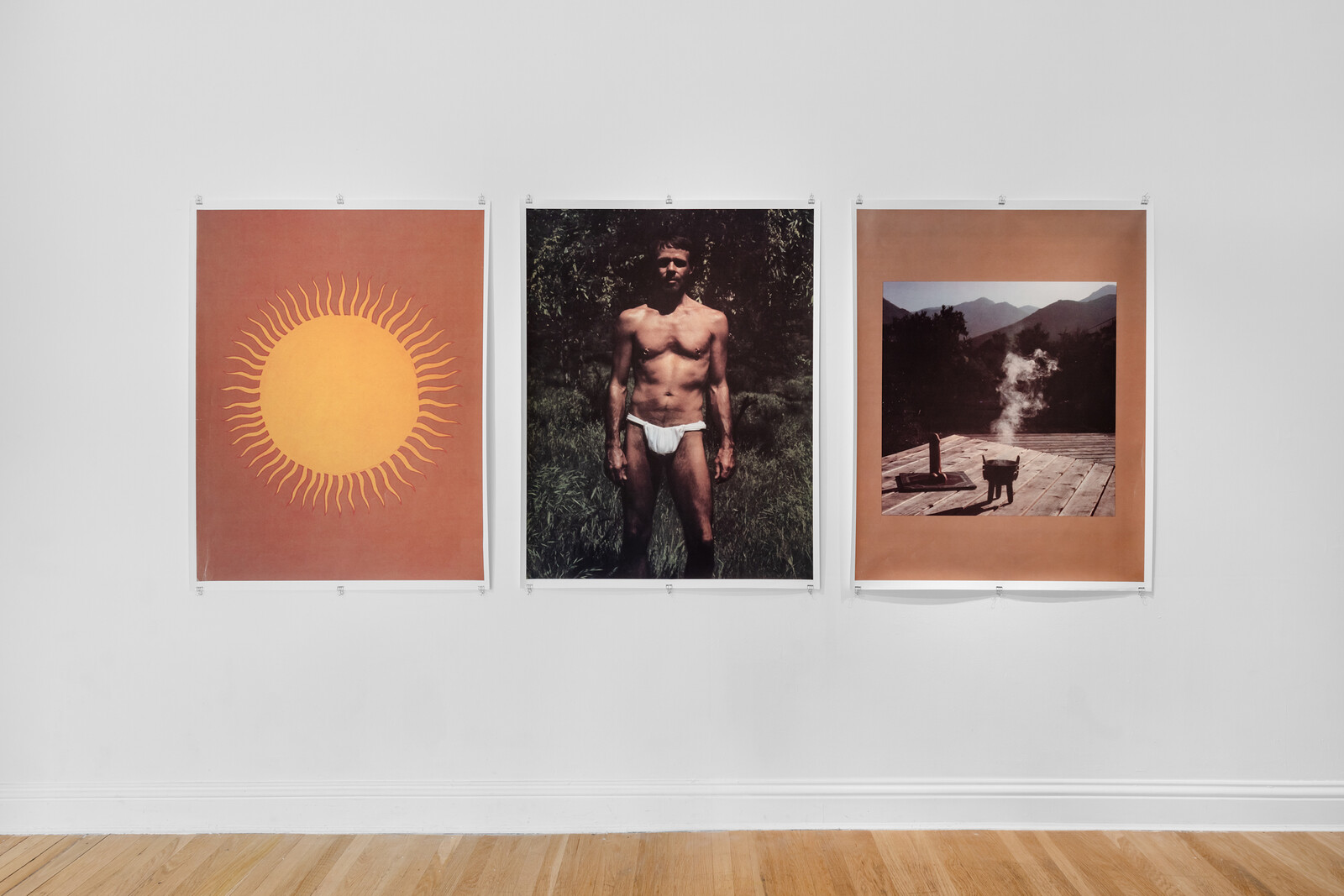

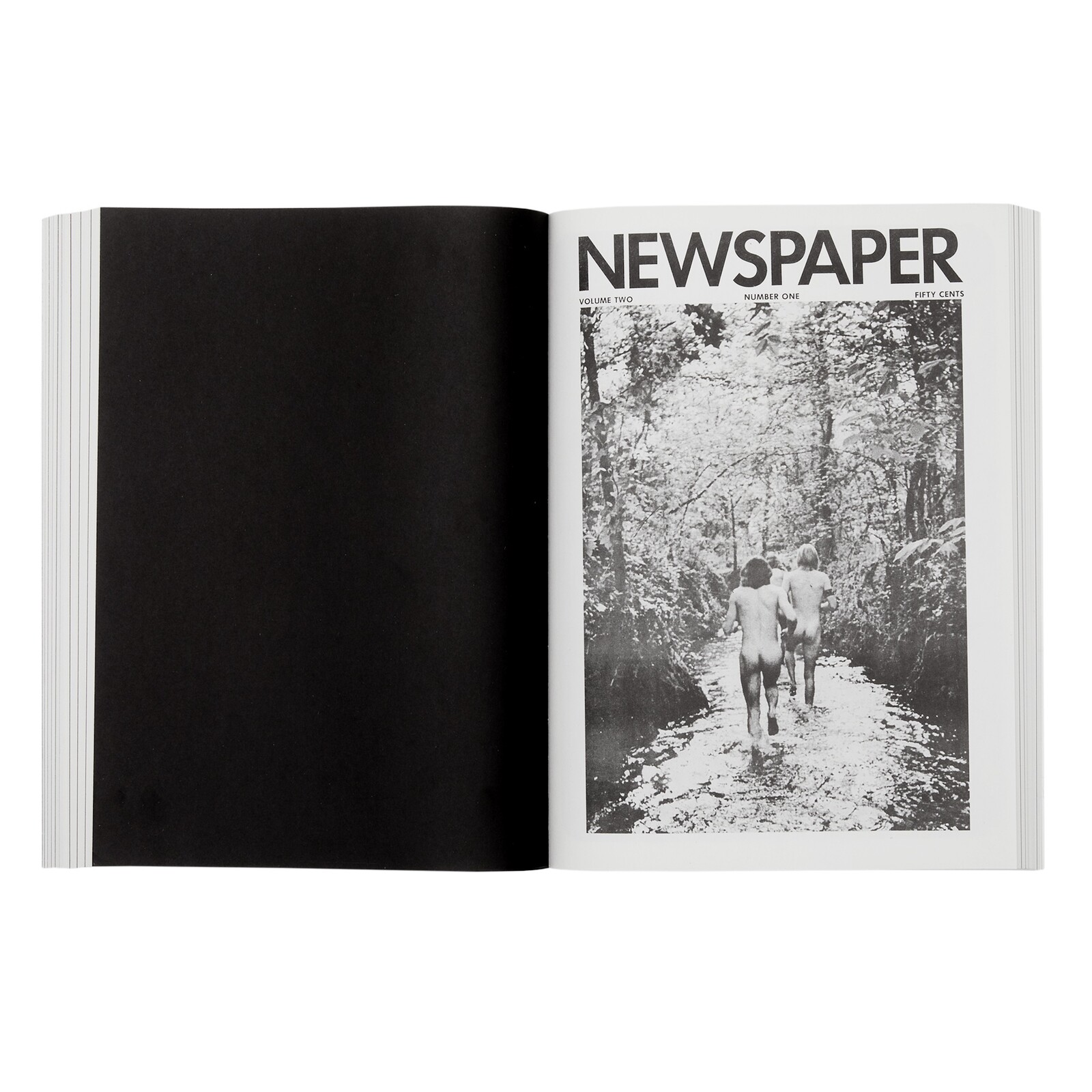

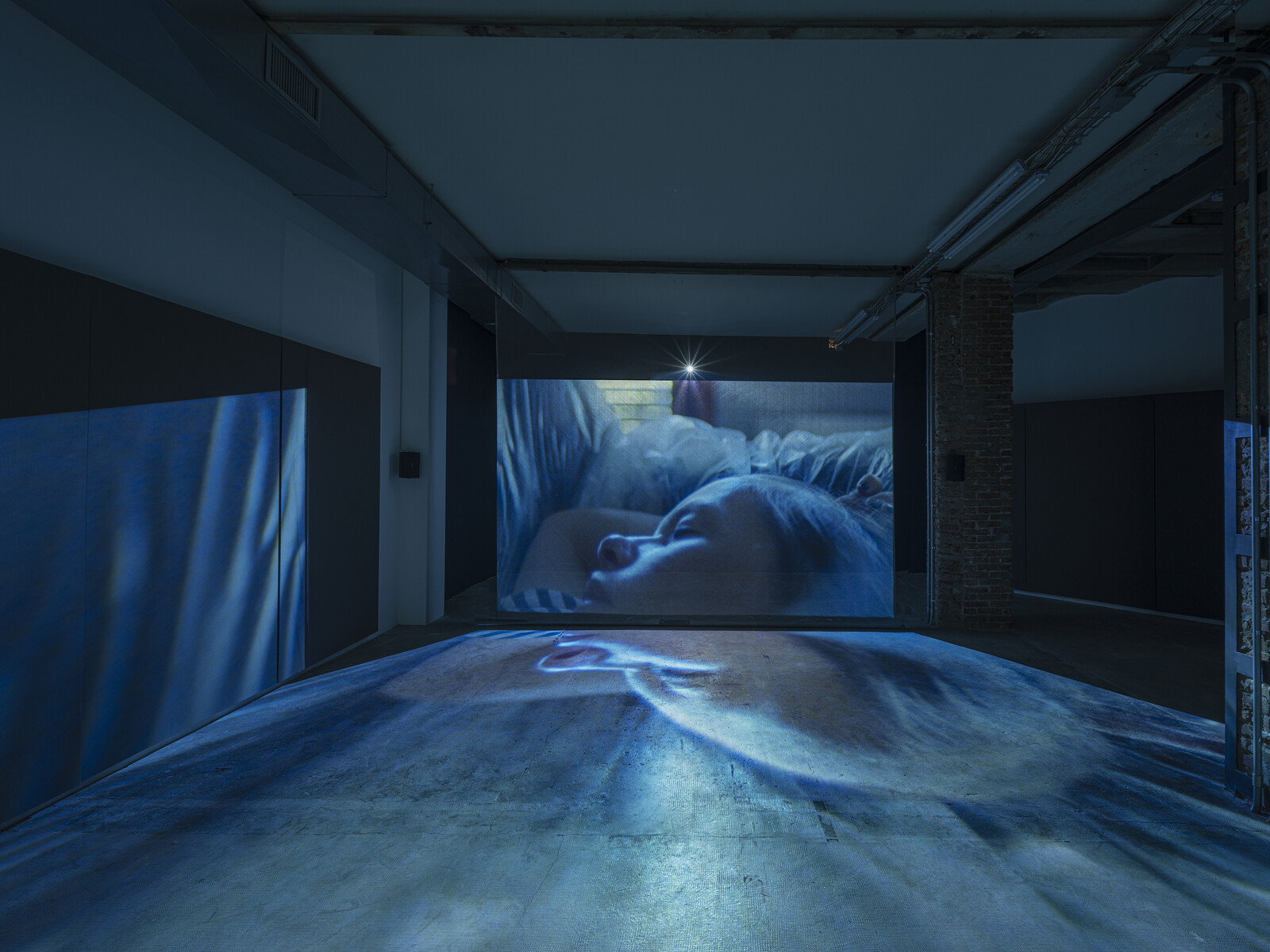

Sam Ashby’s “Sanctuary”

Dylan Huw

Sam Ashby’s film Sanctuary (2024), which forms the centerpiece of this solo exhibition, examines the architectural and psychic remains—and perhaps under-explored potential—of a queer spiritual community founded, in the seventies, by onetime film director Christopher Larkin. When Larkin’s 1974 directorial debut, the gay romantic drama A Very Natural Thing, met a lukewarm critical and audience reception, he reacted in the way gay men throughout history have confronted such disappointments: by packing his bags and fashioning himself a new identity. Larkin lived nomadically for much of the remaining decade, sustained by family money and the liberating atmospheres of Fire Island and San Diego, before re-emerging as the sexual guru Peter Christopher Purusha Androgyne Larkin.

The pursuit of all-consuming spiritual ecstasy by means of fisting, and other anally focused activities, formed the basis of his teachings. These were inflected equally by New Age pop psychology and, more improbably (or not), by his experiences as a young Catholic monk. The prophet set forth his doctrine in his book The Divine Androgyne According to Purusha (1981), a remarkable document of then-nascent fetish culture which documents his quest for “cosmic erotic ecstasy in an Androgyne bodyconscious,” seeking extreme sexual pleasure as a method of obliterating …

October 22, 2024 – Review

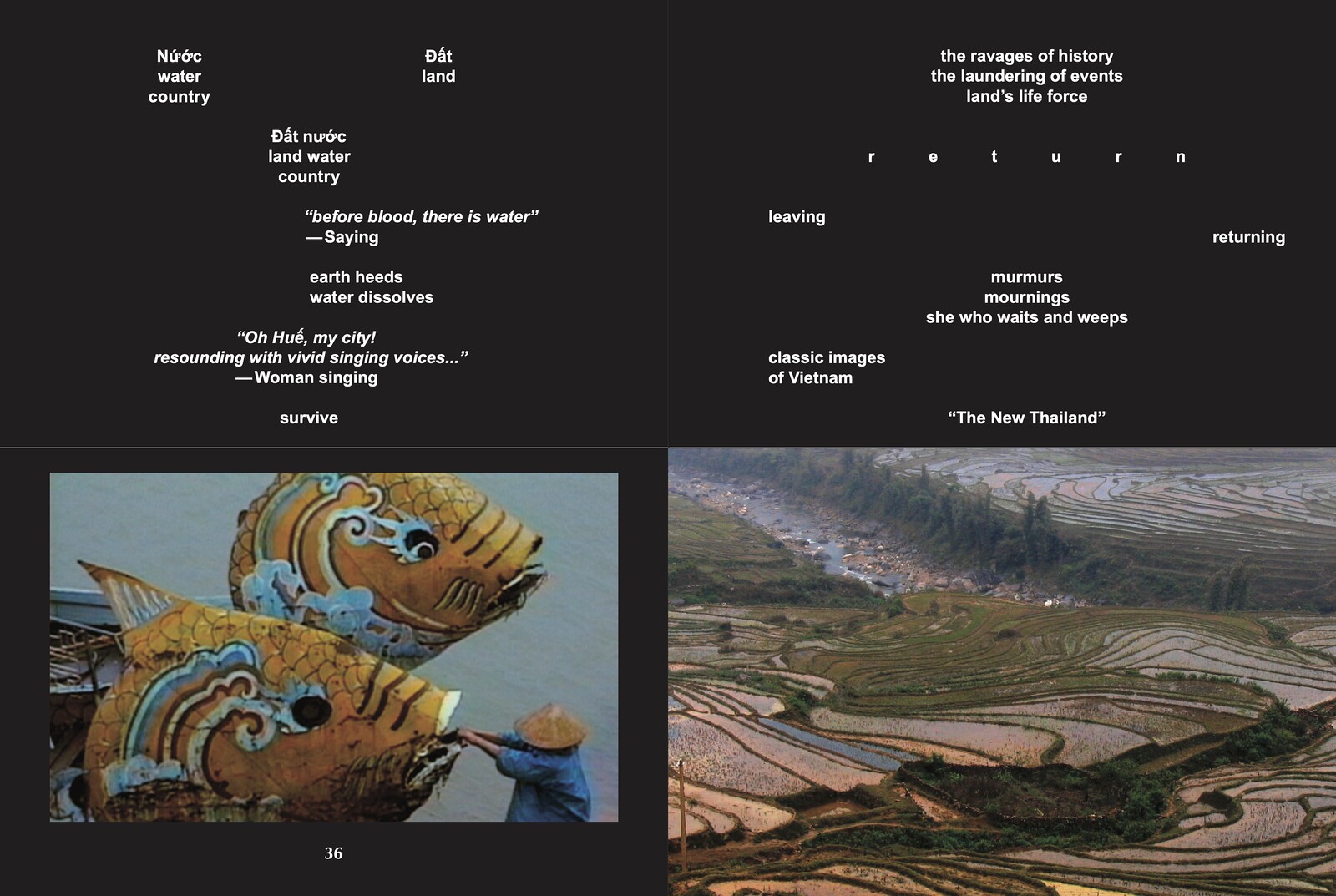

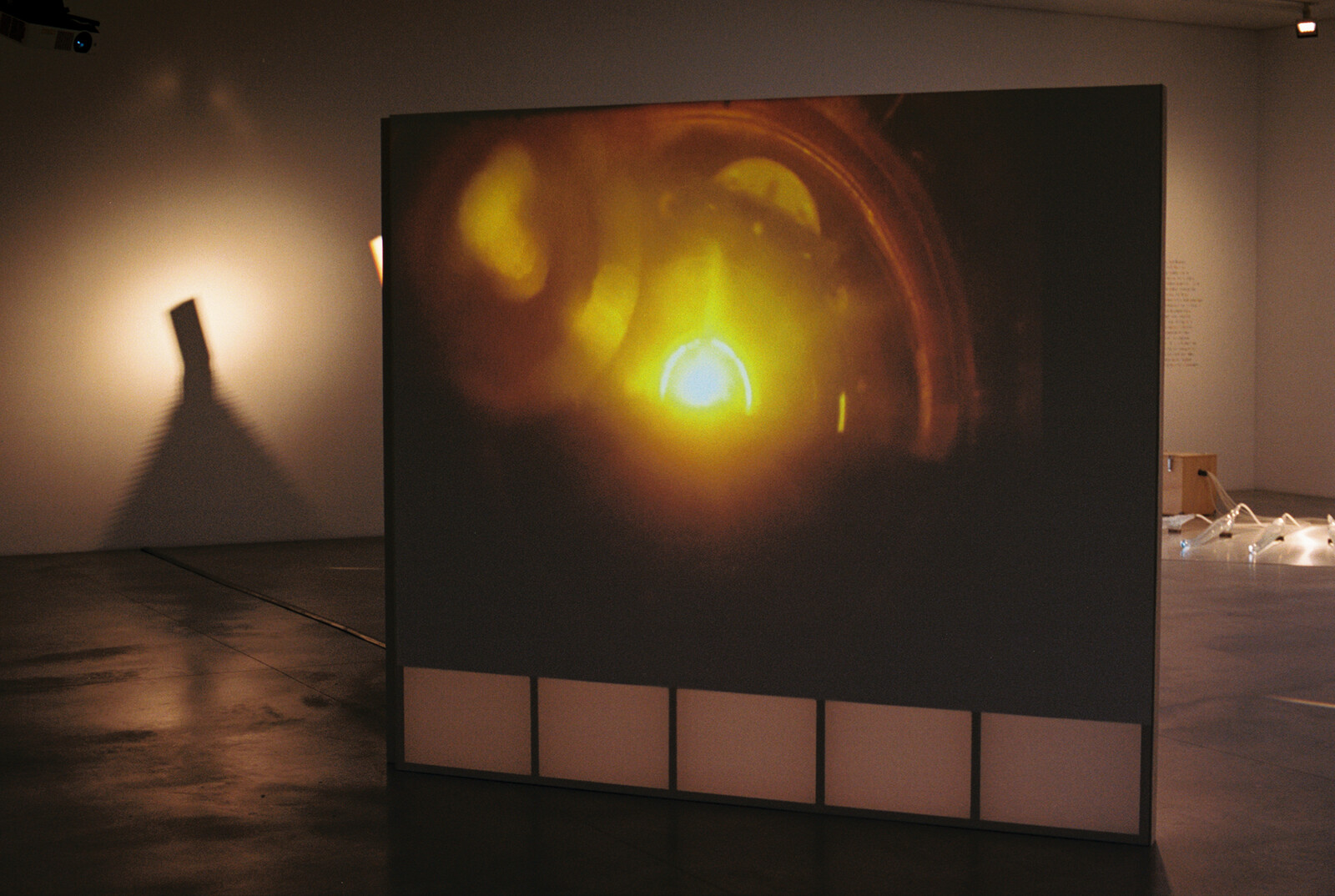

Art Labor’s “Cloud Chamber”

Stephanie Bailey

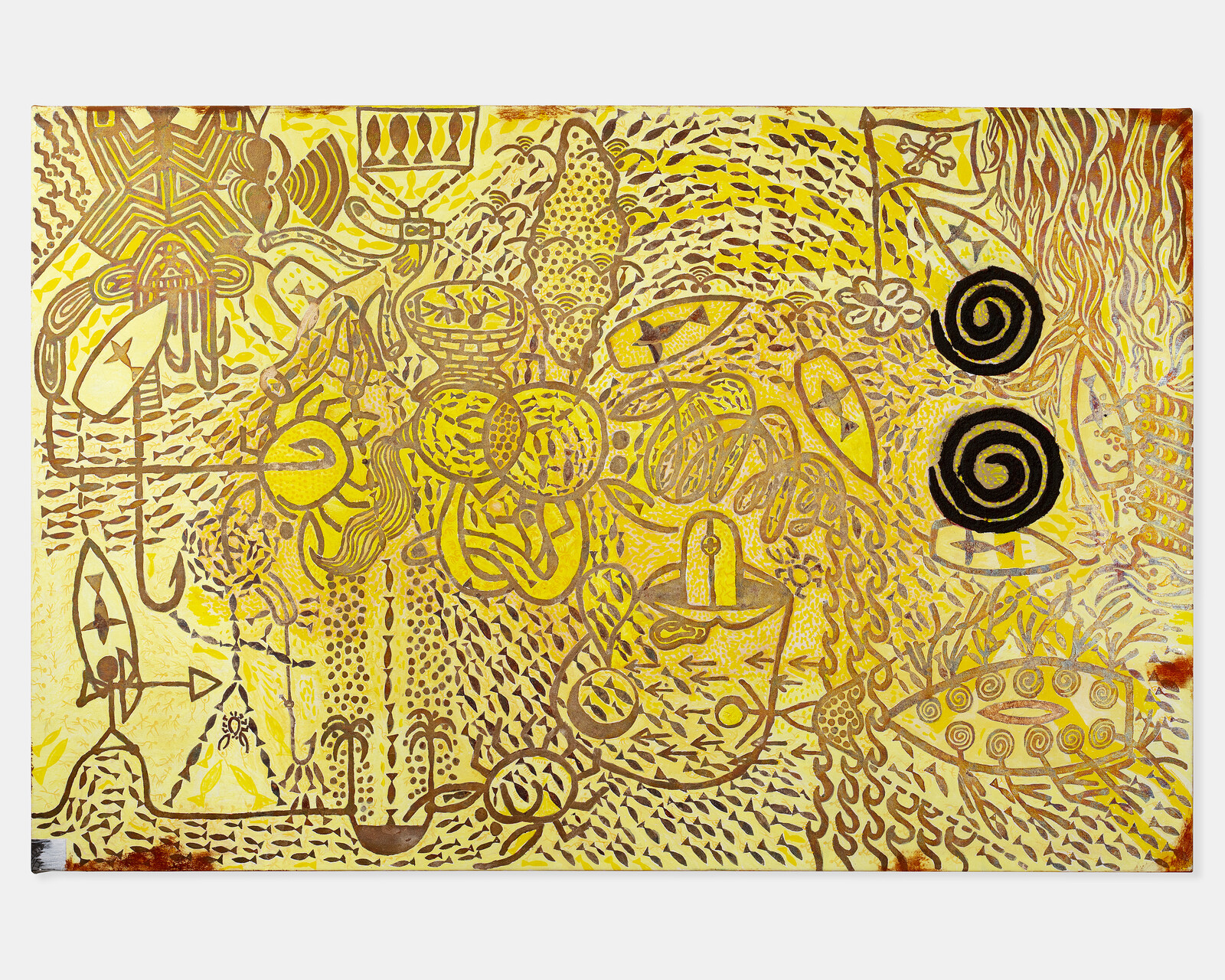

Referring to the cà phê võng providing rest and refreshment to drivers on Vietnam’s provincial highways, this first institutional survey of Art Labor’s activities, curated by Celia Ho, opens with an invitation: to sit (or lie) on a hammock and drink Vietnamese coffee brewed from robusta beans grown in the country’s Central Highlands. The staging of this vernacular rest-stop performs a spatial reconfiguration. No longer are we in Hong Kong, but somewhere in Tây Nguyên, located within the Southeast Asian Massif known as Zomia, its complex textures expressed by a chorus of sculptures, installations, and instruments created by Art Labor—founded in 2012 by artists Thao Nguyen Phan, Truong Cong Tung, and Arlette Quynh-Anh Tran—and collaborators from the Indigenous Jarai community, with whom Art Labor have been working since 2016, alongside invited artists. Among them is musician and artist R Cham Tih, whose standing bamboo instruments in the gallery embody the recuperation of lost Jarai musical traditions through restorative innovation. While K’loong Put (2024) is a traditional xylophone, albeit with additional notes, Klek Klok (2024) is a new design drawing on traditional bamboo gongs used to deter wild birds from the fields.

A dialectics of loss and recovery infuses this exhibition, …

October 18, 2024 – Feature

London Roundup

Chris Fite-Wassilak

A BlackBerry phone in a vitrine plays a short video: a nighttime shot of a building on fire. The scene is familiar to anyone who was in London during the 2011 unrest that grew out of the police shooting of Mark Duggan: the House of Reeves furniture store in flames, caught on both shaky handheld phone and swooping helicopter footage, broadcast and shared over and over. In the next room in Imran Perretta’s “A Riot in Three Acts” at Somerset House is a meager set, as if belonging to an abandoned play, with a few benches plonked amongst pebbles strewn with rubbish, a large backdrop painted with a nondescript shopfront.

This is Reeves Corner in Croydon, where the burnt-out building once stood. A soundtrack of swelling strings fills the room—a quick-paced march, followed in a later section by soaring high notes—and adds narrative tension and the hope of redemption to Perretta’s non-film. Melodrama is part of the point here: while listening, I’m creating a mental film loaded with scenes shaped by that news footage, and bumped up with film conventions. History repeats itself, Perretta’s restaging suggests, first time as tragedy, second time as Hollywood special.

The causes of the 2011 …

October 17, 2024 – Review

Gregg Bordowitz’s “Dort: ein Gefühl”

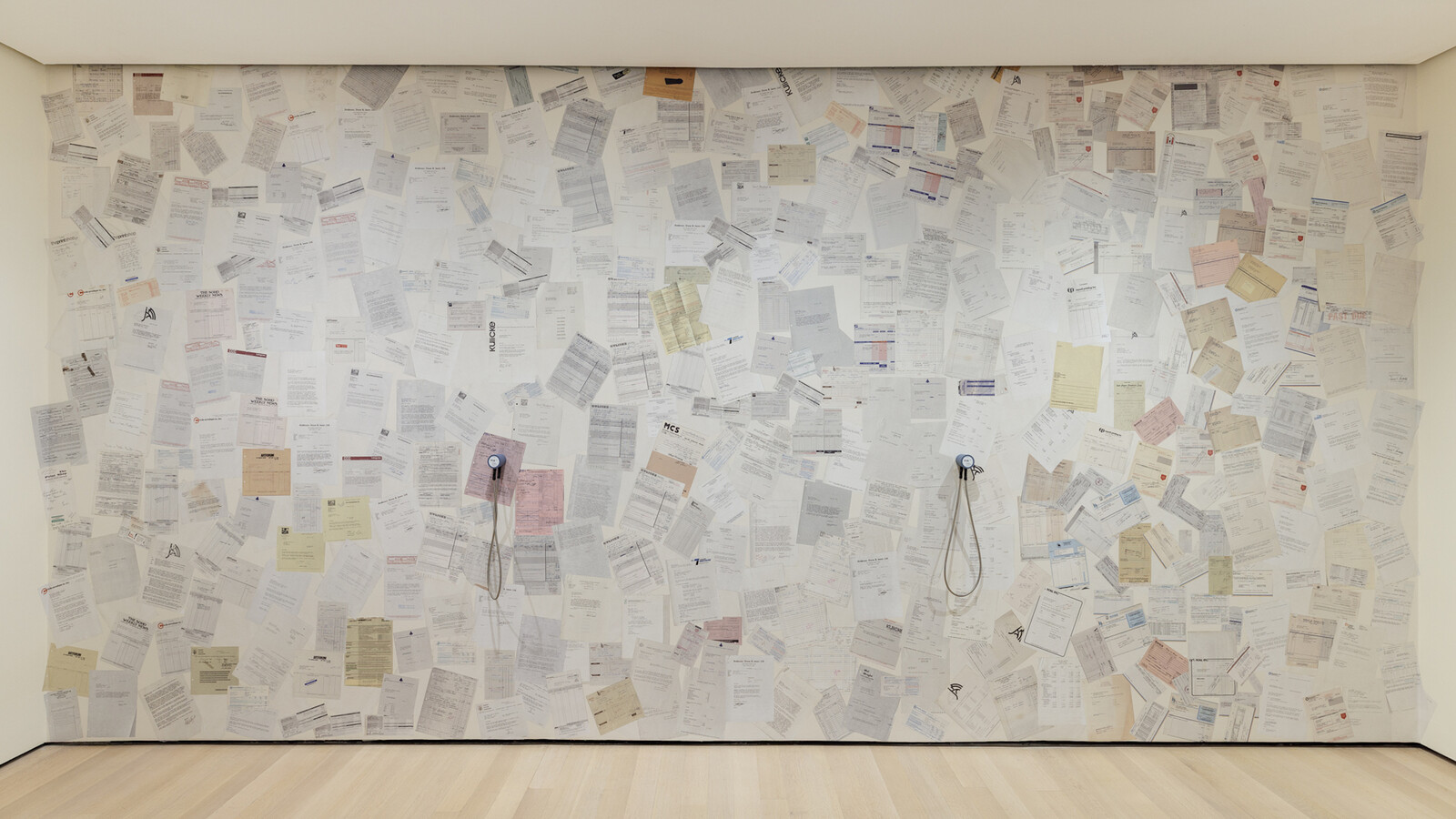

Kirsty Bell

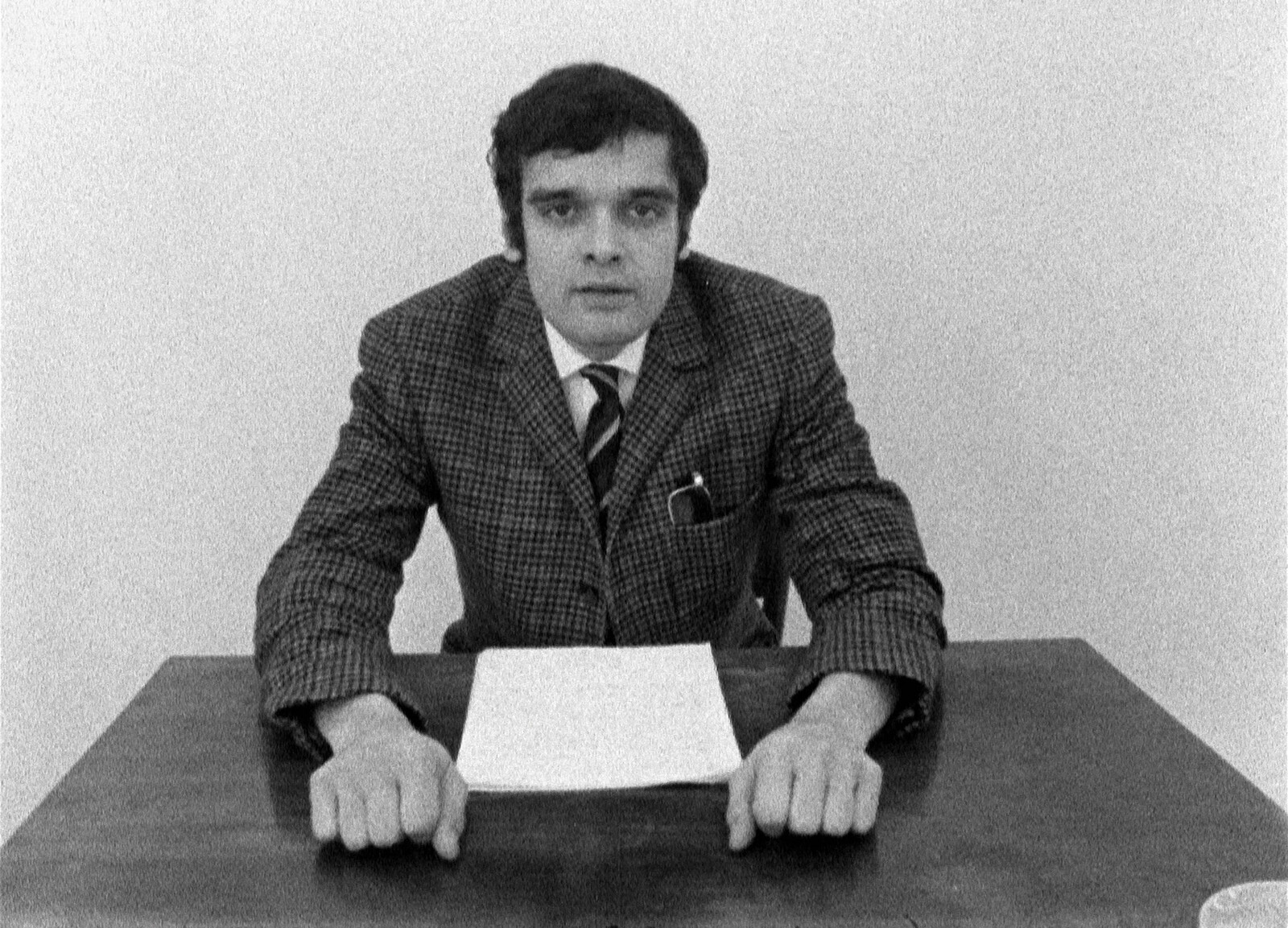

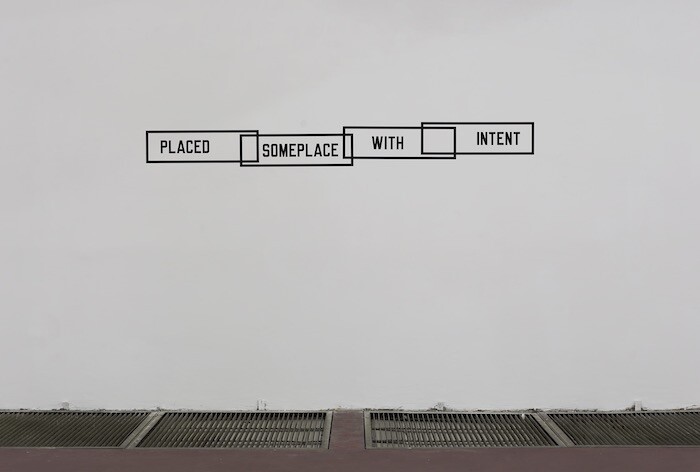

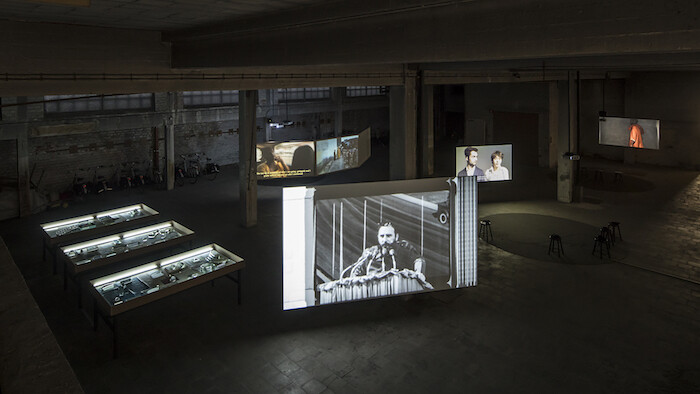

Gregg Bordowitz has been writing, publishing, performing, and teaching consistently and prolifically since the early nineties in New York, making “agitprop” videos as an AIDS activist and member of ACT UP. Though his material output is slim, his wordcount is substantial. Rather than focus on the early activist works for which he is best known, this exhibition concentrates on writing as the core of his artistic practice, but also as a daily habit—“writing as an activity of thought,” as Kunstverein Director Fatima Hellberg puts it—that becomes material testament to his ongoing presence, as a long-time survivor of HIV.

To create an exhibition from this ephemeral practice is audacious, particularly in the Kunstverein’s cavernous former flower market hall, but Hellberg has a track record of conjuring shows from unruly or nebulous bodies of work (David Medalla’s 2021 retrospective, for example, or the large-scale solo exhibition of Georgian artist Tolia Astakhishvili in 2023). In the absence of discrete objects, the exhibition relies on subtle gestures, the first of which is a narrow red line affixed to the wall, three inches from the floor, that follows the entire perimeter of the exhibition space. It establishes intention and constructs a kind of “holding environment,” …

October 15, 2024 – Review

Jenna Bliss’s “Basic Cable”

Chris Murtha

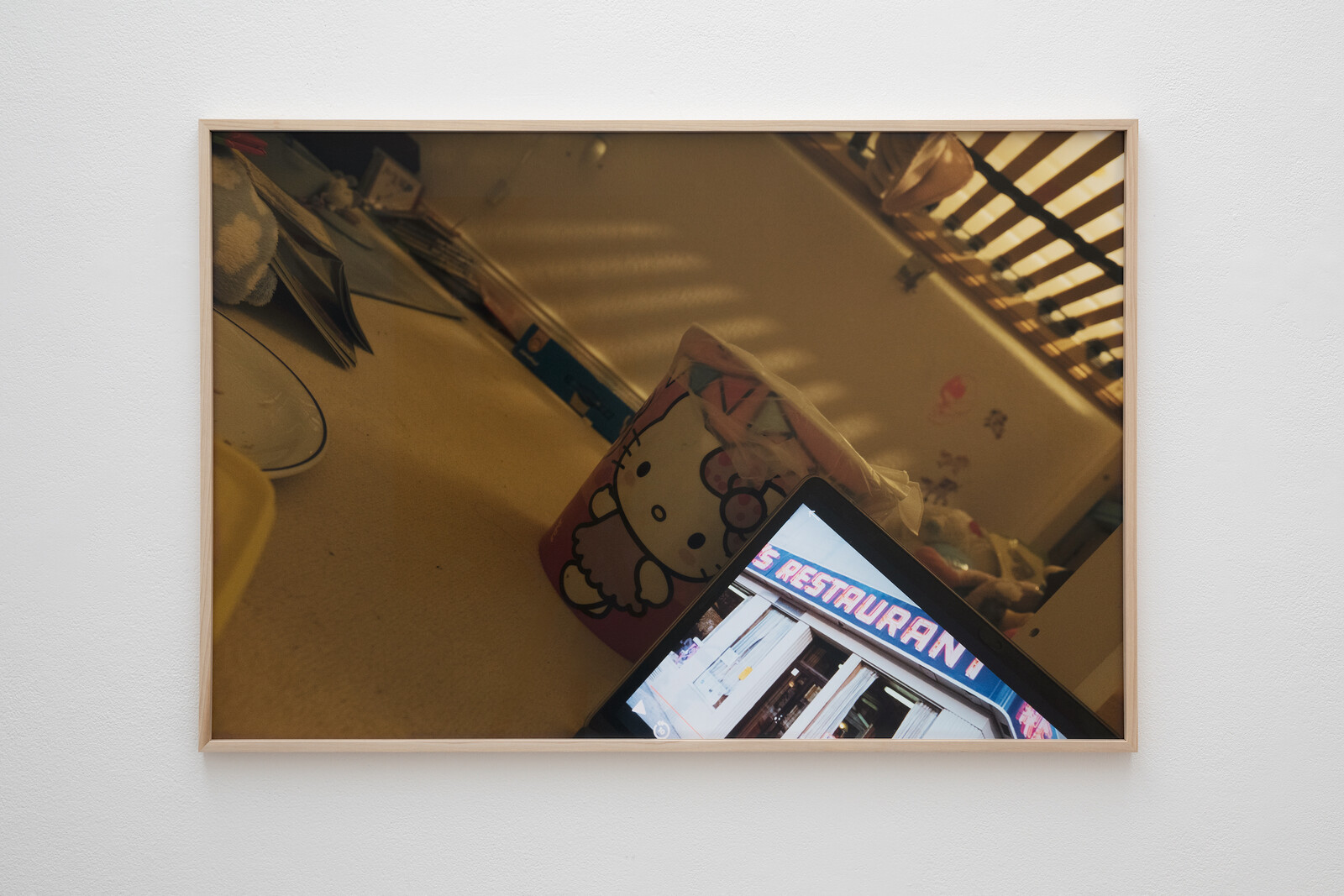

The idea of “Wall Street,” a metonym for global capitalism measured against whatever remains of “Main Street,” has far outgrown its connection to the New York thoroughfare that traces the path of the city’s seventeenth-century border wall. Today, the home of the New York Stock Exchange is heavily secured by bollards, fences, and barricades that regulate and restrict public access. Armed with her camera, native-New Yorker Jenna Bliss roams the narrow canyons of Lower Manhattan. Her unsteady lens lingers on passersby and commercial storefronts; gazes skyward to scale gleaming towers; and hovers, from afar, on the skyline’s iconic, yet ever-morphing silhouette. With the September 11 attacks, the 2008 financial crisis, and the Covid-19 pandemic as inflection points, Bliss blends fact with fiction, past and present, to probe our collective perception of Wall Street as a place and an idea—from the ground up.

To produce the Super 8 films and photographic lightboxes on view at Amant, Bliss splices and recombines her material so that her subjects are neither fully revealed nor entirely obscured, but rather held in disorienting tension. Conspiracy and Spectacle (both 2021 and under two minutes long) loop continuously on box monitors mounted atop tall pedestals arranged to mimic …

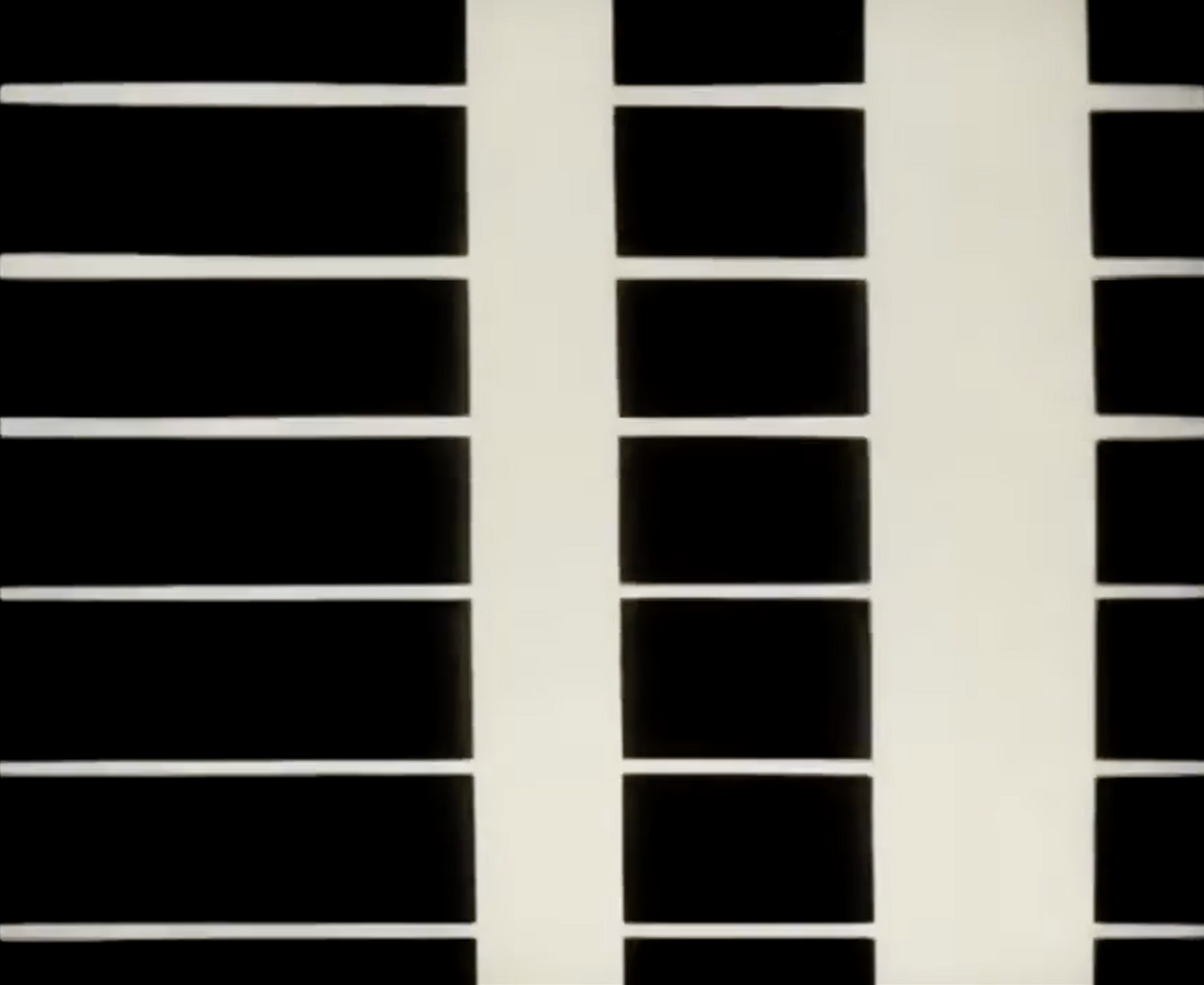

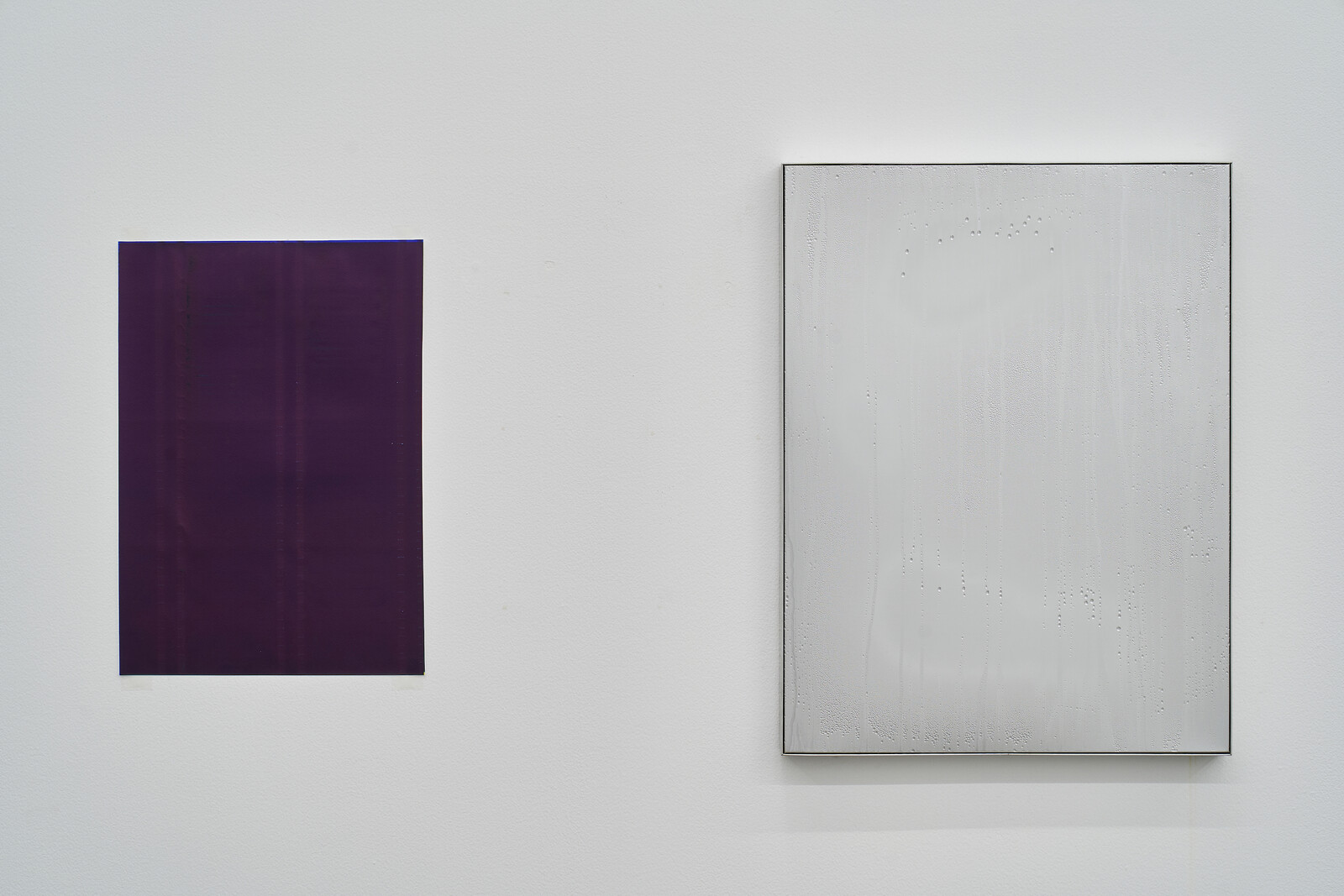

October 11, 2024 – Feature

Jo Baer

Rachael Rakes

Jo Baer nicknamed the five large-scale abstract paintings that compose “The Risen” (1960/61–2019) series her “zombie” works. Despite living in Amsterdam for the past forty years, Baer remains associated with the American minimalist movement, both for her works and for her bold public engagements (and squabbles) with the New York art world’s sculptors, critics, and dealers. Destroyed by the artist in the early 1960s, before which they were documented by Polaroid photographs, the “Risen” paintings were recreated in 2020.

[figure ROSE_JOBAER6]

A few years earlier, the term “zombie formalism” was omnipresent in Western art criticism. A condemnation coined by Walter Robinson, it referred to an abstraction that had come back into favor in casual collusion with the speculative market, and suggested that an aesthetic not formed by new ideas but by a final evacuation of whatever shred of meaning was allowed to live within abstract painting. This notion came and went quickly in the currency of hot takes, but it hints at the changes and some lingering positional uniformity in art criticism in the six decades between Baer’s conception and recreation of these works.

Neither era’s discourses have sufficiently contended with Baer’s minimalist project, which found its stride and distinctive …

October 9, 2024 – Feature

Carrie Rickey’s A Complicated Passion: The Life and Work of Agnès Varda

Brian Dillon

I once met her, if you could call it that, for a few seconds at the Frieze Art Fair; she turned to the person who introduced us and asked: “Is he going to look after me?” She must have meant it ironically, because in 2009, a decade before she died, Agnès Varda was not only busier than ever—after photography and film, she had lately embarked on her “third career” as an installation artist—but honored as a New Wave instigator and a pioneer feminist director. Also, to her delight, more and more beloved as an eccentrically turned-out presence on the film-festival and art-fair circuits: beneath the lifelong bob and variegated dye-job, she might turn up in silk pajamas, purple tracksuit (both by Gucci), or dressed as a potato. Varda’s last years formed a giddy and heartening coda to a life and a body of work that were playful and profound. And an artist who, if Carrie Rickey’s new biography of her is to be trusted, was utterly tireless on every front, artistic or intimate.

Varda was born in Brussels in May 1928—her parents named her Arlette, because she had been conceived in Arles. When the Nazis invaded Belgium in 1940, the …

October 8, 2024 – Review

Gustav Metzger’s “And Then Came the Environment”

Rob Goyanes

Gustav Metzger hated cars. Not only for the pollution and noise, but because of their association with the hermetically sealed “gas vans” that Nazis used as mobile extermination chambers, diverting exhaust fumes into the vehicles’ interiors. Conceived but not realized for the United Nation’s first world conference on the environment in 1972, Metzger’s installation Project Stockholm, June (Phase 1)—finally executed for the Sharjah Biennial in 2007—included 120 cars, parked around a clear rectangular structure, their motors running constantly and filling the space with gas. The resonances with the United Arab Emirates (one of the world’s largest oil economies), and Los Angeles itself, site of this exhibition, are clear.

Metzger died in 2017, at the age of 90. When Hauser & Wirth started representing his estate three years later, it marked the first time that his work had been shown in one of the commercial galleries that he memorably described as “Capitalist institutions. Boxes of deceit.” “And Then Came the Environment” is one of more than seventy exhibitions and events in the Getty’s Southern California–wide PST ART: Art & Science Collide initiative. Featuring works made between 1961 and 2014, the show positions the artist in its press materials as an advocate …

October 4, 2024 – Review

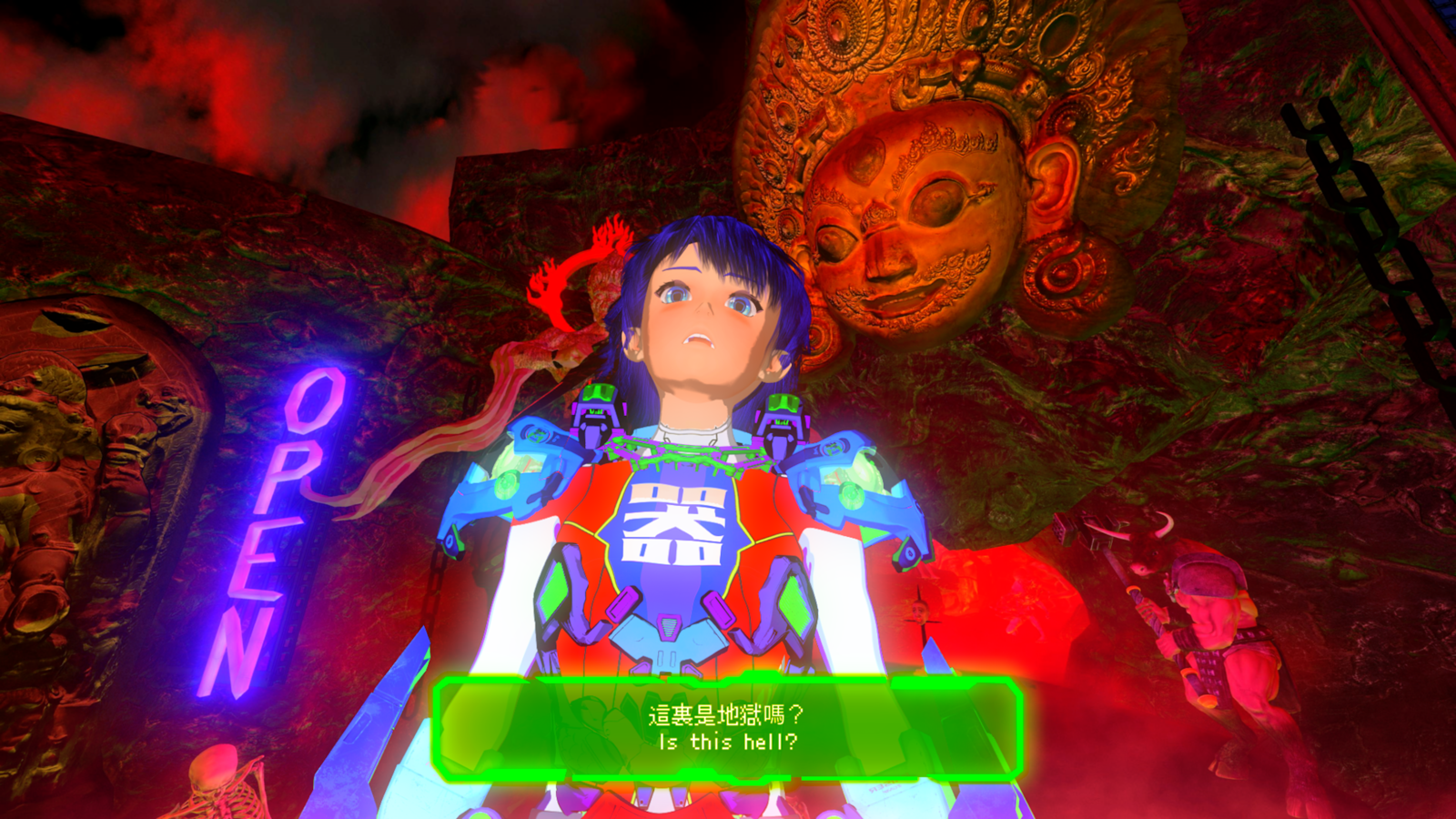

15th Gwangju Biennale, “PANSORI: A Soundscape of the 21st Century”

Ben Eastham

The main exhibition of the 15th Gwangju Biennale is entered via a gloomy “sound tunnel” filled with dissonant noise and leading into a silent room resembling an abandoned office space. The ceiling tiles of Cinthia Marcelle’s installation There Is No More Place in This Place (2019–24) are disarrayed as if by some natural disaster, and the scrambling of the senses effected by these two environments marks a promising start to an exhibition that pledges to “reflect our new spatial conditions and the upheavals of the Anthropocene.”

The central show at Gwangju Biennale Exhibition Hall is spread across five floors that the visitor ascends from ground level. The atmosphere in its lower reaches is apocalyptic, exhausted, and dystopian, an aesthetic of broken wires and fragmentary ruins gathered under a dismal light and typified by an impressive series of monumental sculptures by Peter Buggenhout resembling John Chamberlain’s junked cars. Yet where the American artist conjured both the joy of the open road and the horror of the high-speed crash, Buggenhout’s crumpled architectures set the tone for the opening’s relatively narrow—and notably dour—emotional register.

Their collective title, “The Blind Leading the Blind,” neatly captures the impression that visitors to an exhibition curated by …

October 3, 2024 – Feature

On Gego, Miguel Braceli, and the Reticuláreas

Mónica Amor

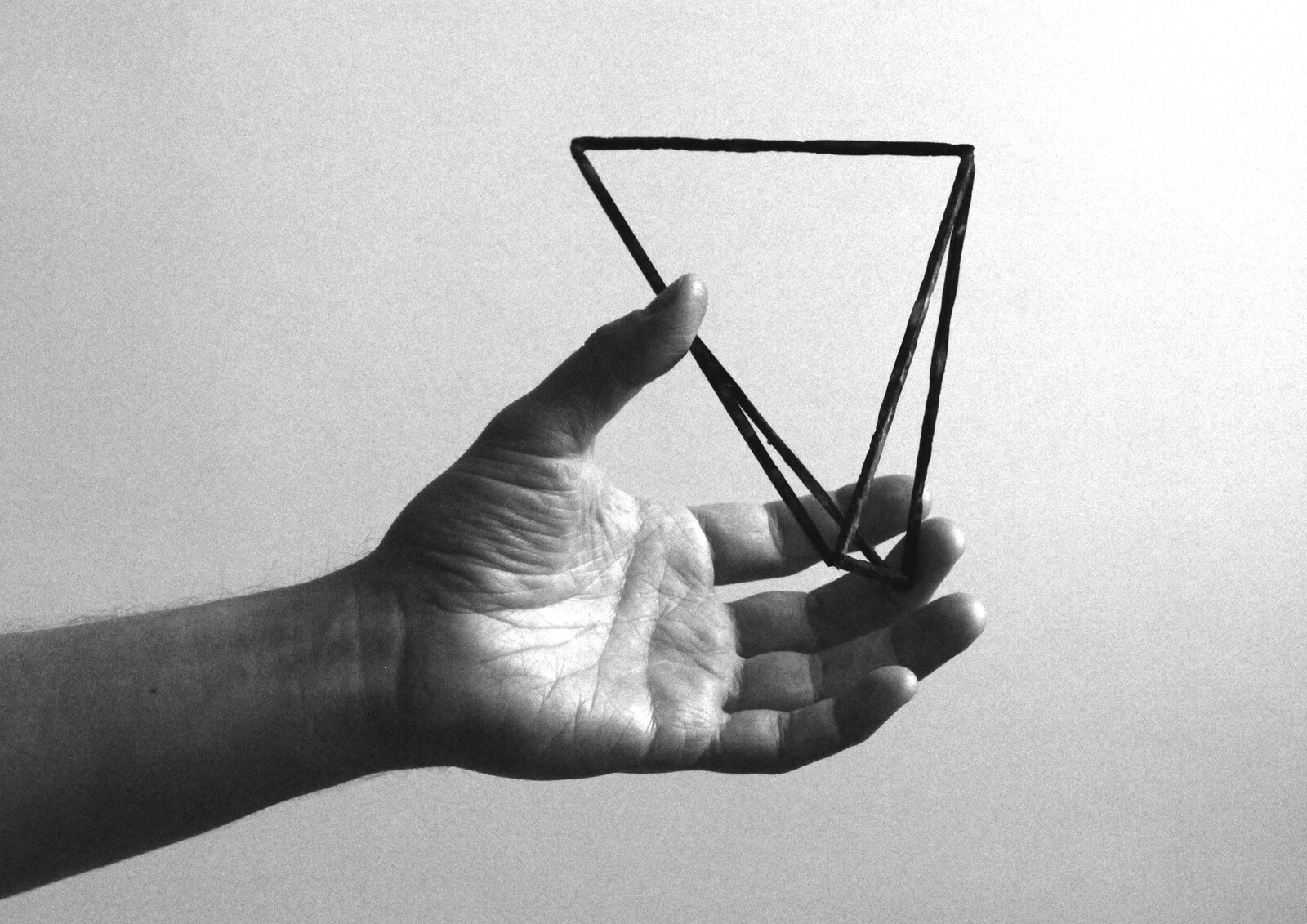

In a fit allegory for a country Luis Pérez-Oramas once defined as a “wasteland republic,” one of Venezuela’s greatest twentieth-century artworks remains out of sight, its status uncertain. Reticulárea—an environment made of metal nets, based on triangular modules, that hang from the ceiling and surround the viewer—was realized by the German-born artist Gego (1912–94), who arrived in Caracas in 1939 with a degree in Architecture and Engineering but no more than a few words of Spanish. First shown at the Museo de Bellas Artes of Caracas in June 1969, it was thereafter remade for several exhibitions until a room was dedicated to it in 1980. Since 2002, it has rarely been available for viewing, a limitation, attributed to conservation issues, which seems to have become permanent around 2009 (exact records are unavailable). In 2017 the work was deinstalled, losing both its form and its place, and rendering its absence total.

Despite this, the work has been germinal to contemporary Venezuelan art: its photographic record securing its reputation as a pioneering aesthetic proposal. The recent flowering of Gego’s international renown as a radical abstractionist who revolutionized postwar sculpture rests on the work’s refusal of volume, mass, monumentality, and its embrace of …

October 1, 2024 – Editorial

Something I was doing

The Editors

In a piece soon to be published by e-flux Criticism, Mónica Amor reflects on Gego’s Reticulárea, an environment constructed out of metal nets that surround viewers and bind them into a network. Commissioned as part of a series exploring the contexts out of which significant works of art emerge, Amor’s essay proposes that Gego’s work expresses a nonhierarchical collective experience, its “decentered logic” a model for the emotional and intellectual infrastructure that constitutes a shared cultural inheritance and which must regularly be refreshed in order to survive.

Amor traces the ways in which a work informed by the artist’s life as an architect and educator in Caracas established a model that has been adapted to the present by the Venezuelan artist Miguel Braceli. By inviting dispersed and often disenfranchised communities into the collective production of his works, he proposes an effective means of protesting—and working against—the fragmentation of Venezuelan society.

Fittingly for this month’s editorial program, which features several pieces on how culture might foster solidarities without becoming exclusionary of others, the relevance of Reticulárea extends far beyond the borders of its homeland and the moment of its first exhibition in 1969. Now removed from view, Gego’s work continues …

September 27, 2024 – Review

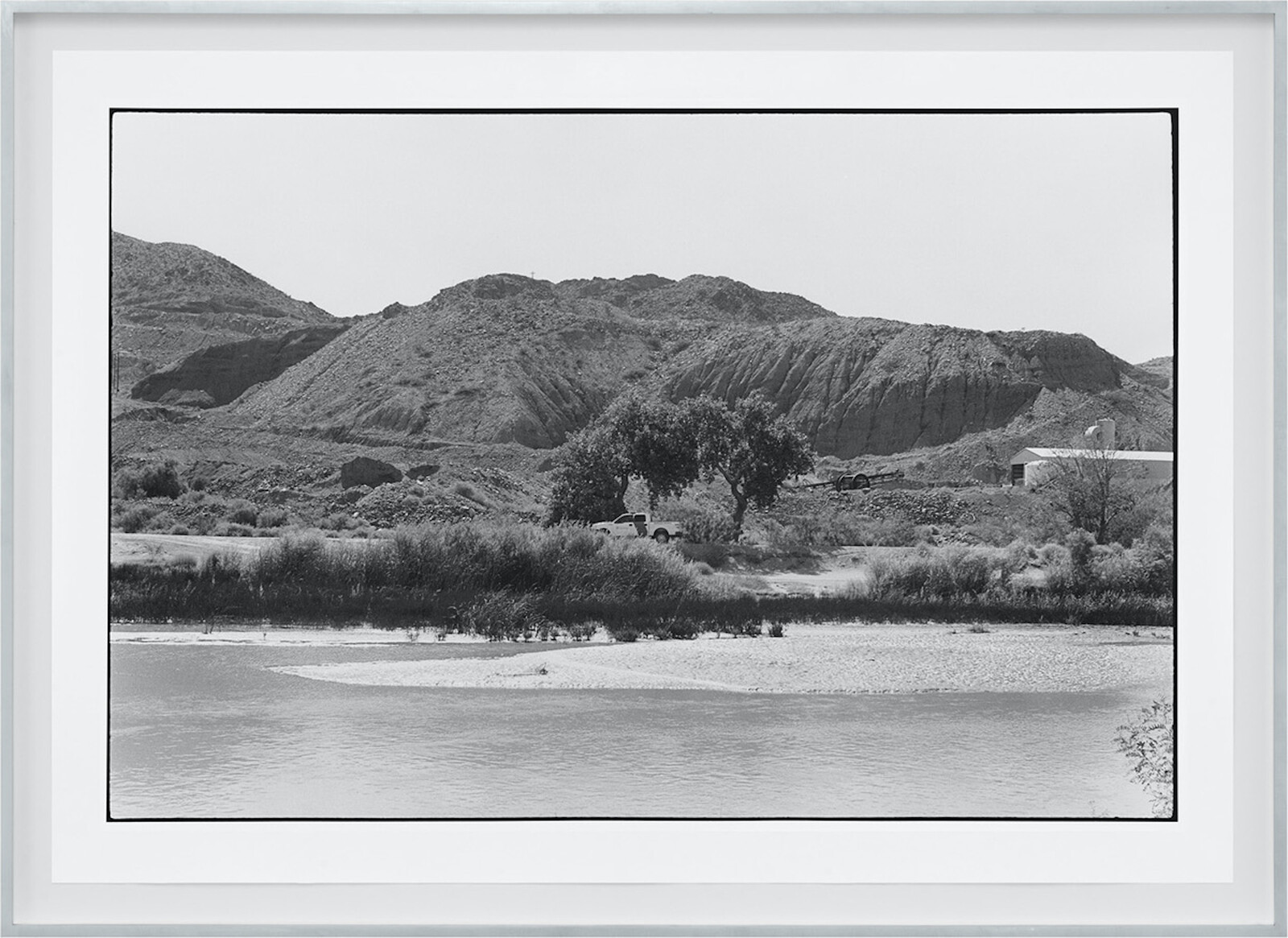

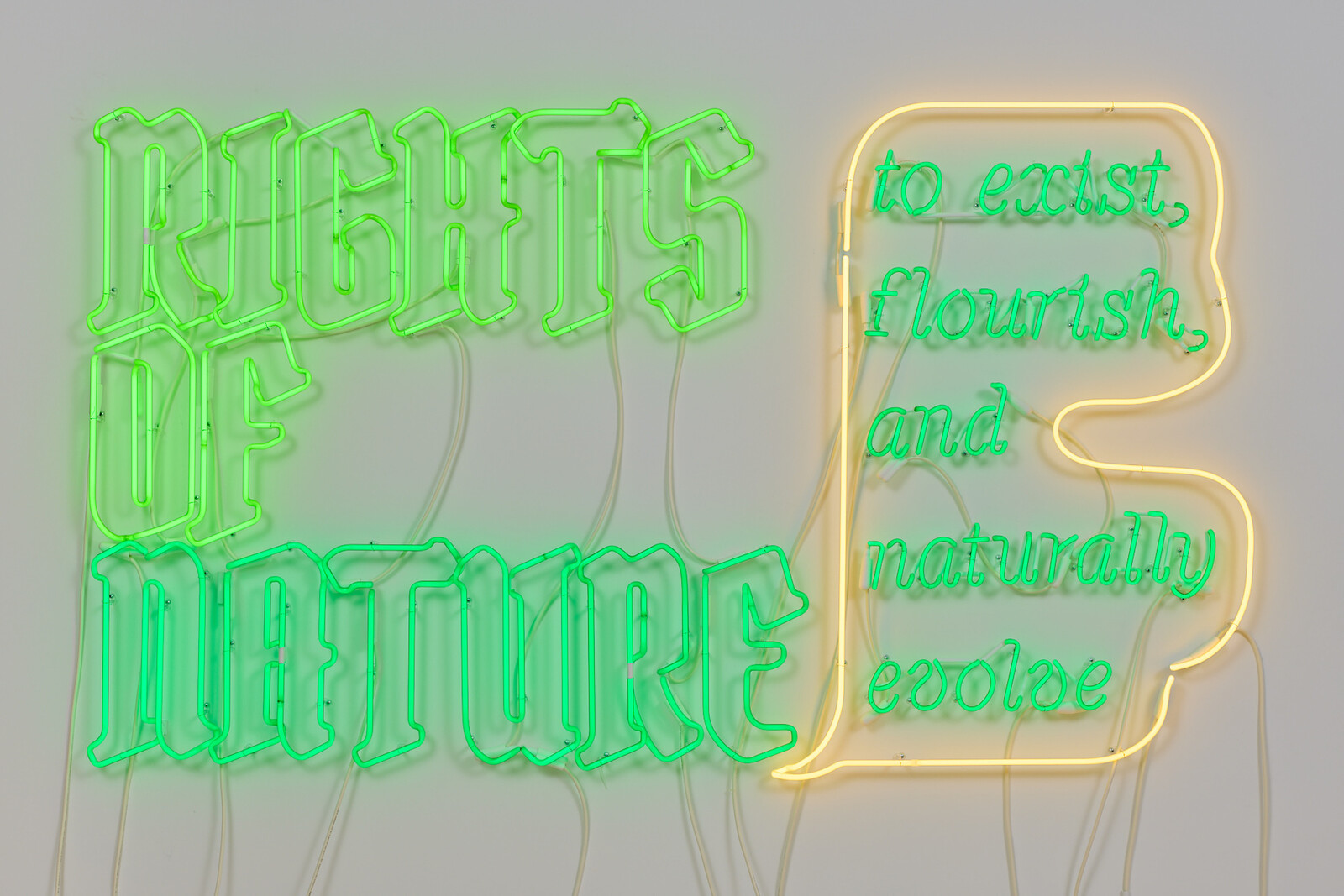

Steirischer Herbst ’24, “Horror Patriae”

Jörg Heiser

A hard rain had been falling the week before the opening of Steirischer Herbst, the annual art festival in the Austrian city of Graz. The river running through the Styrian capital was wild with uprooted trees after floods that, in northern Austria, left five dead. The catastrophe took on greater significance given that it coincided with the run-up to the general election on September 29, the polls for which are led by the far-right populist Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ.) and its brazen climate change denialism. Riffing on the Lord’s Prayer, their billboard address to the electorate—Euer Wille geschehe (Your will be done)—looked less enticing submerged in brown floodwater.

And so the billboard project by Vienna-based Yoshinori Niwa got off to a perfect start, having appeared two days before the opening in the center of town. As I walked by, I observed a police officer on her walkie-talkie, anxiously awaiting instructions. The nervousness was caused by Niwa’s parody of a FPÖ. election poster, in which an “EPÖ.” party announces Jedem das Unsere (To Each Our Own, playing on the infamous slogan at the entrance to Buchenwald concentration camp) and candidate “Dr. Steinapfel” holds a bratwurst to his ear. The poster …

September 26, 2024 – Review

Survival Kit 15, “Measures”

Xenia Benivolski

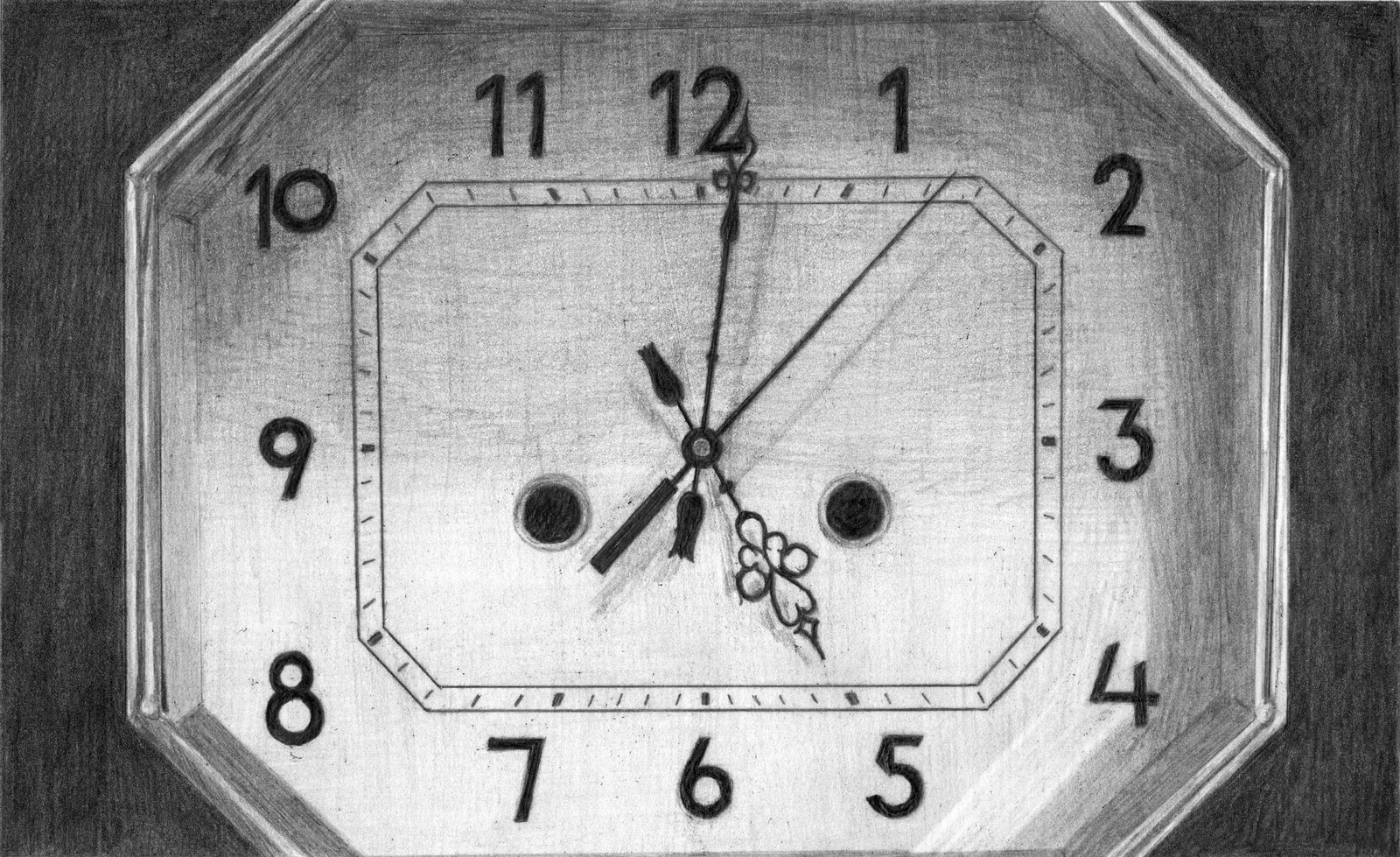

Can belief bring things into being? There’s a theory that the word “Riga” derives from the ancient Livonian word “Ringa,” which implies a closed loop or ring—a shared reference to its circular harbor and the cyclical history that animates it. This explanation has been widely accepted, despite being disproven; it’s an urban myth which has—perhaps due to its lyrical charm—become a kind of truth. Many works in this year’s edition of Survival Kit, curated by Jussi Koitela, playfully straddle the line between fact and fiction, exploring degrees of constructed truths that hold special meaning to the city residents. Based in a former civic legislation building where bureaucrats once made decisions, and in a local hub across the river, the exhibition forms a bridge between Riga’s different hemispheres, timelines, and generations.

Survival Kit is a festival born out of necessity in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crash, when people began leaving Latvia to find work elsewhere, shrinking Riga’s population by about a third. Its mission was to animate the empty spaces left behind by people and industry, preserving local history and potentiality through the creation and layering of new meanings. Not all of them are here to stay. Linda Boļšakova’s installation …

September 25, 2024 – Review

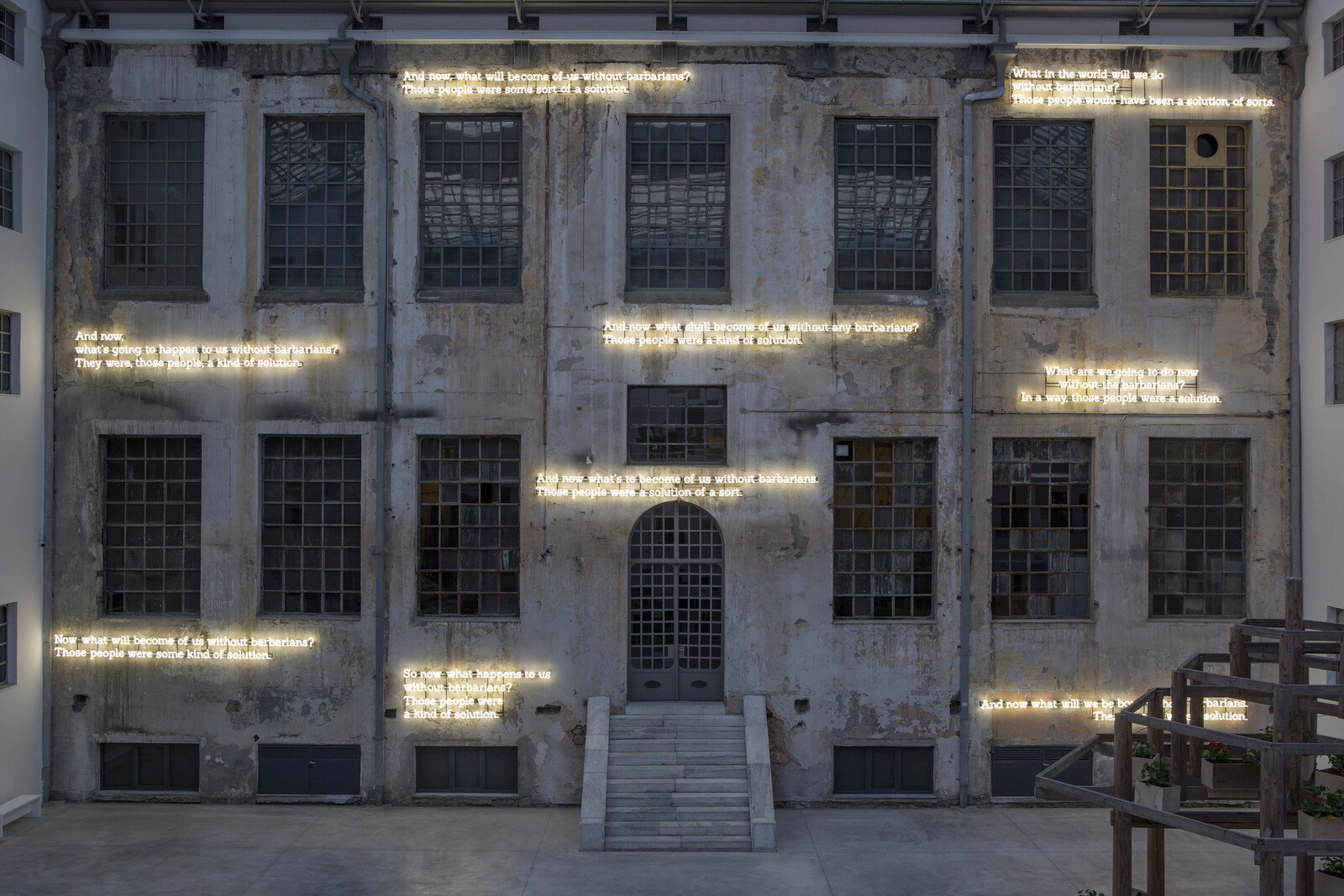

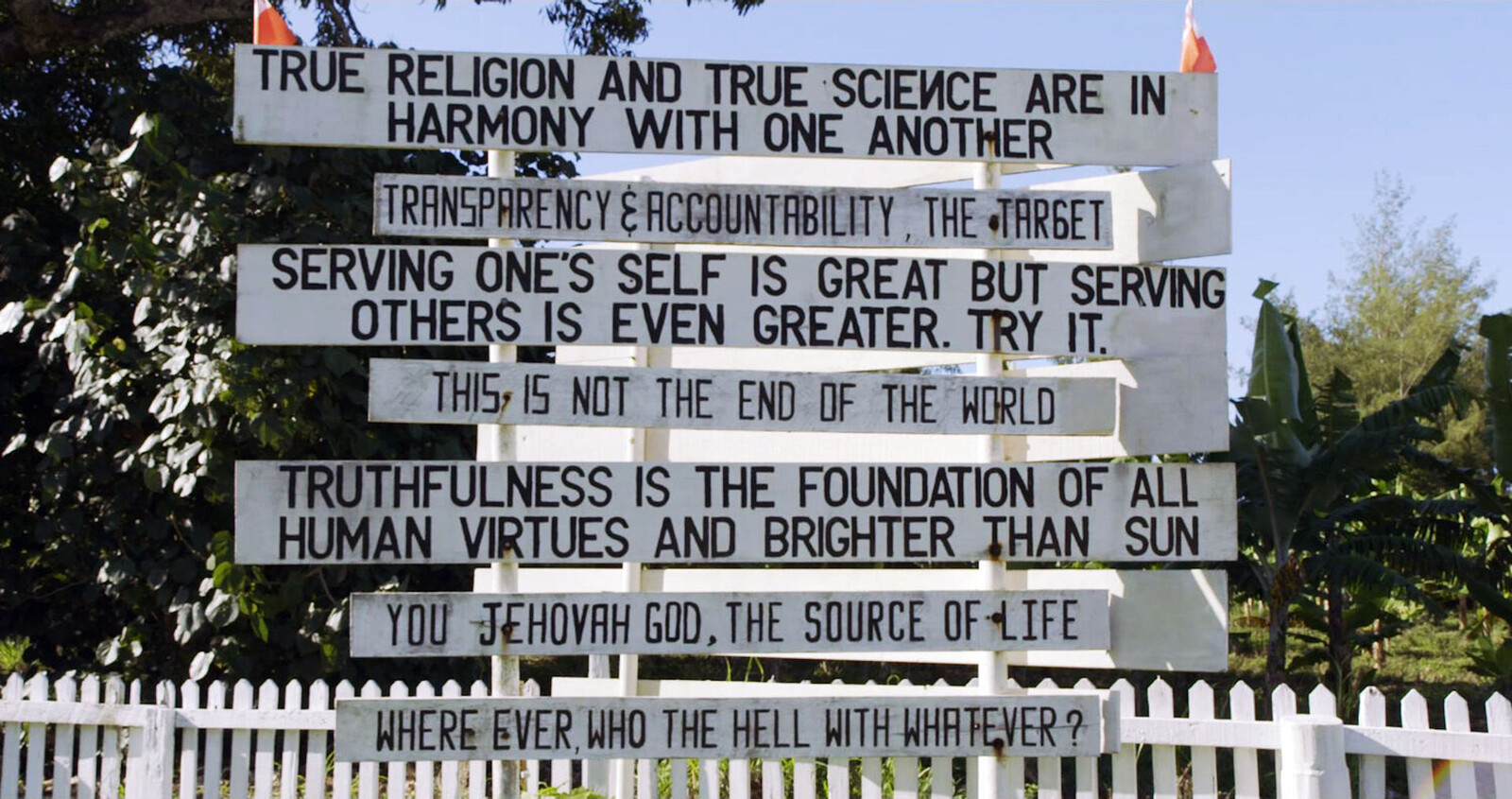

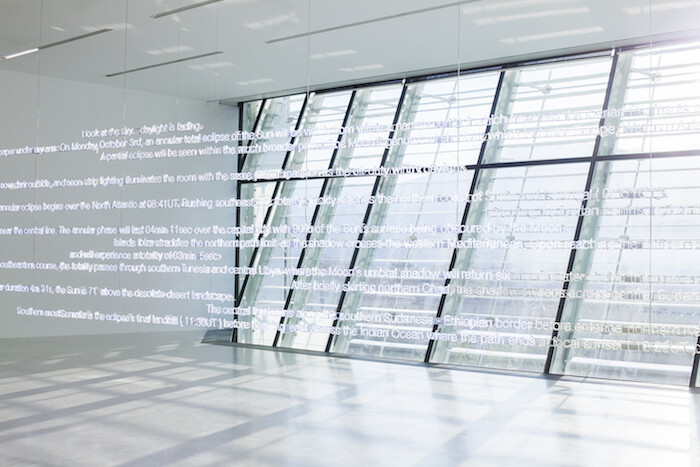

Jenny Holzer’s “WORDS”

R.H. Lossin

Jenny Holzer began making her ongoing series of “Truisms” in 1977. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, truism indicates “a self-evident truth, esp. one of minor importance; a statement so obviously true as not to require or deserve discussion. Also: a proposition that states nothing beyond what is implied in any of its terms.” The word “truism” means more or less the same thing as “platitude” or “cliché”—unremarkable, banal observations—but the fact of its orthography nudges it, just slightly, toward a charged moral terrain of reality and deception.

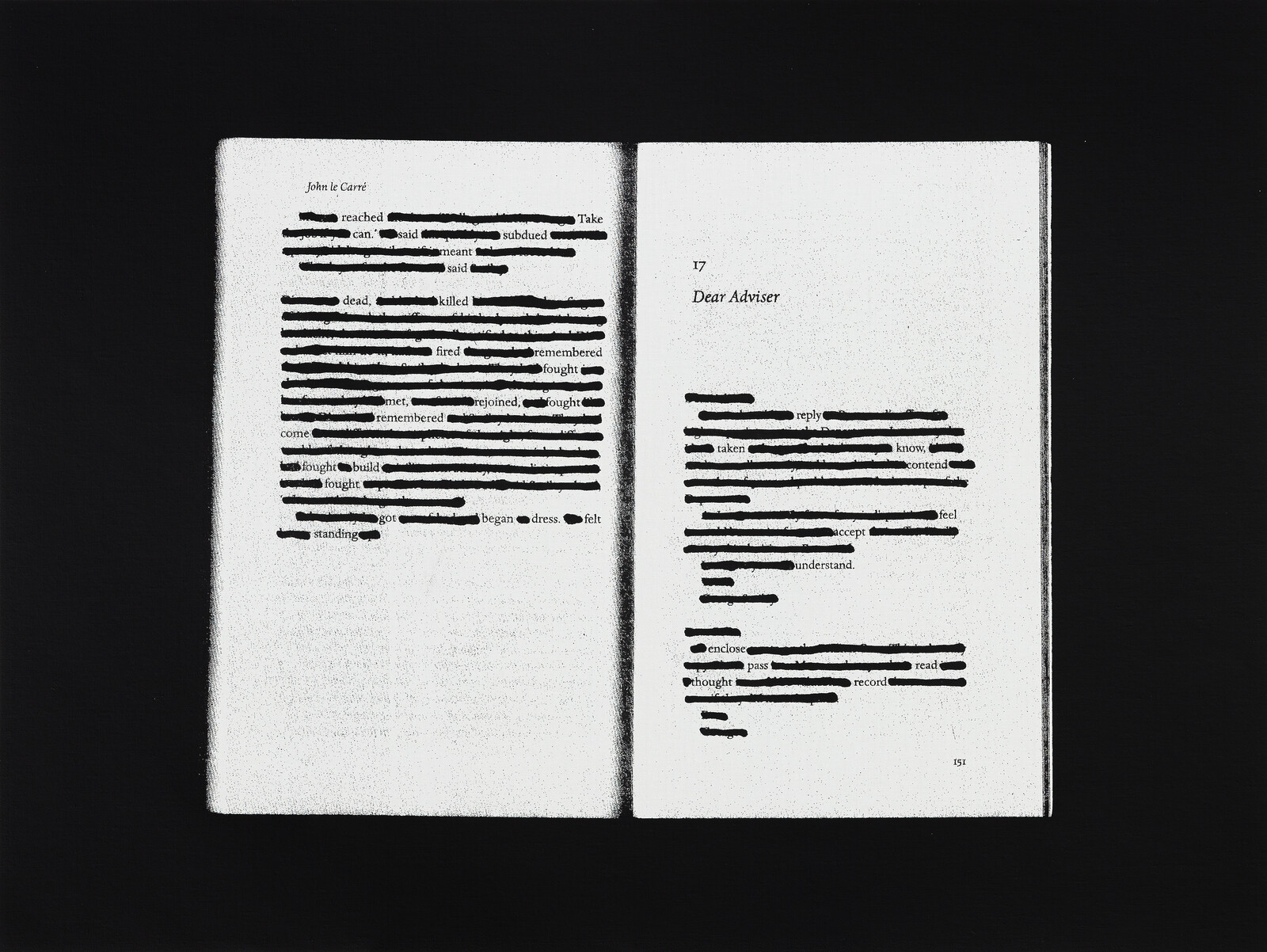

Today the word’s appearance, unlike its synonyms, reminds us how contentious such a notion of obvious and easy truth has become. The same statement is either widely repeated nonsense or unquestionable fact depending on who you ask. This has always been the point of Holzer’s text-based works. “Truism” underscores the tension produced by common sense and capital T truth that animates her scrolling digital billboards, engraved park benches, projections, and painting of redacted documents.

Making strange claims in the form of a brief declarative statement or maxim draws attention to the ways that sense becomes common (or doesn’t) and underscores how difficult, if not impossible, it is to produce …

September 24, 2024 – Review

Busan Biennale 2024, “Seeing in the Dark”

Harry Burke

In his posthumously published book Pirate Enlightenment, or the Real Libertalia (2023), David Graeber traces the impact that stories of Madagascar’s self-governing pirate settlements had upon the invention of Enlightenment reason in the seventeenth century, to make the point that much of what’s thought of as European or “western” thought in fact originates elsewhere. The late anthropologist’s concept of “pirate enlightenment” is a point of departure for “Seeing in the Dark,” on view at four venues in the South Korean port city of Busan.

What does it mean to see in the dark? Our pupils dilate in darkness, letting more light into our eyes. If we still can’t see, we turn to other senses: we listen, we feel. Many works in this biennial explore expanded ideas of visuality, or probe other strategies of multisensory perception. At Busan Museum of Contemporary Art, Sorawit Songsataya’s installation Two Bridges with 7 Notes and 42 Strings (2024) incorporates piles of dried fish and cuttlebone, gathered from Busan’s shorelines and busy markets, to evoke the scents of their granduncle’s fish sauce factory, associating their native Thailand with their family’s diasporic home in Aotearoa. Songsataya has put onyx crystals and dried plants on the sculpture Ranad …

September 20, 2024 – Feature

New York City Roundup

Orit Gat

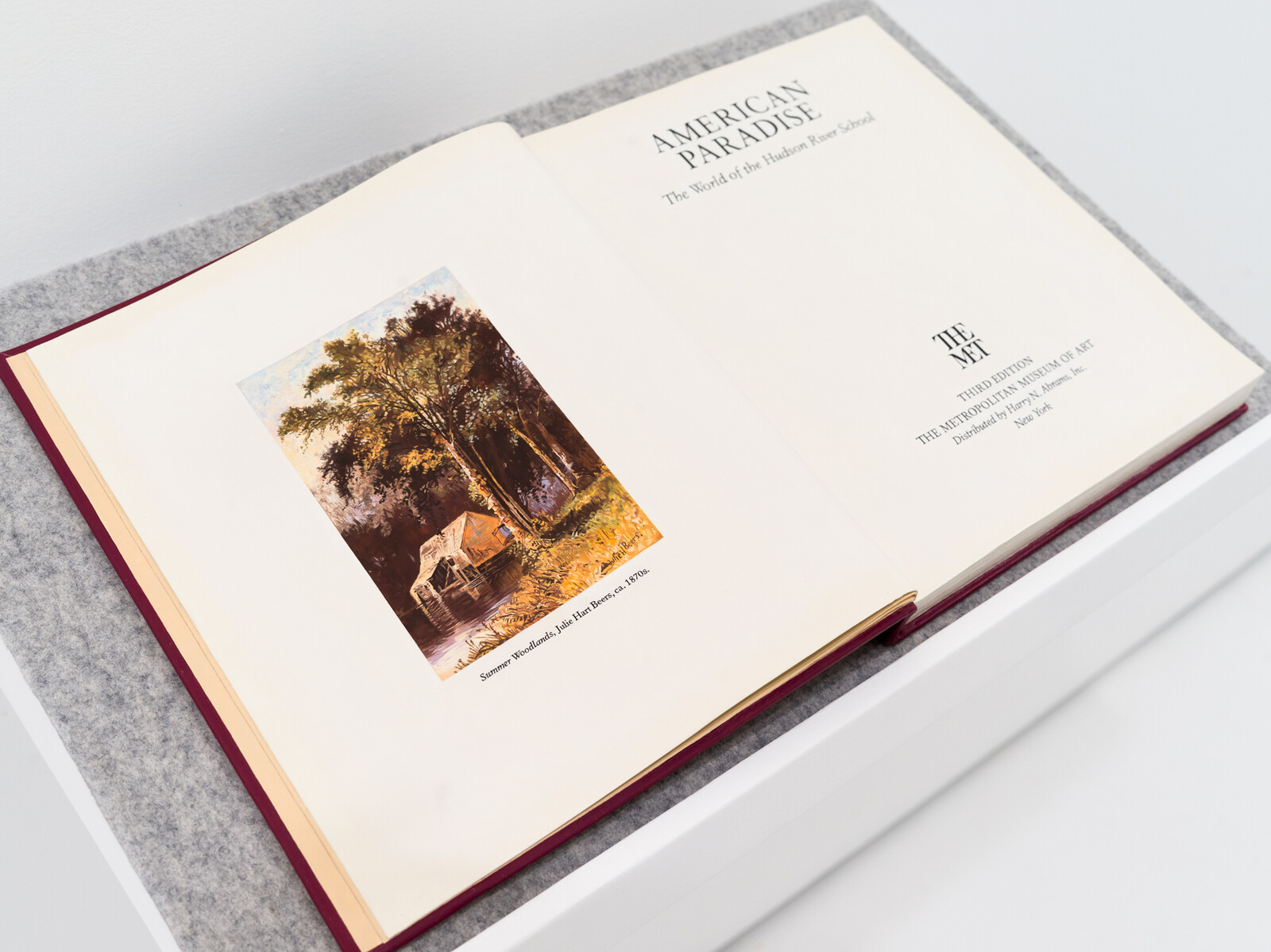

“American Paradise”: Anna Plesset took the title of her show at Jack Barrett Gallery from a 1987 exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art about the nineteenth-century Hudson River School of American landscape painting, which featured twenty-five male artists and not a single woman. Plesset responds by researching the work of women artists of the time, applying an astonishingly skillful trompe l’oeil technique to the task of filling in historical gaps.

Her show opens with a sculpture mimicking the original exhibition’s catalogue, a perfect facsimile in oil on epoxy, aluminum, and steel placed on a plinth. Ostensibly the catalogue’s third edition (only one edition was published), the frontispiece is here replaced with a painting by a woman artist, Julie Hart Beers. In Value Study 2: Niagara Falls / Copied from a picture by Minot / 1818 (2021), Plesset paints an impeccable reproduction of the paper printout of an online image search for Louisa Davis Minot’s painting of the waterfalls, as if adhered to the canvas for reference using blue painter’s tape. The canvas itself shows the sketch and a beginning of a copy of Minot’s original. Plesset’s realism is not a remedy for historical injustice but a conceptual stop-and-start, a …

September 19, 2024 – Review

Manifesta 15

Juan José Santos

The defining model of European architecture in the twentieth century is not Bauhaus, Brutalism, Expressionism, or Functionalism; it is the detention camp. This idea is proposed by Domènec’s installation A Century of European Architecture (2024). Displayed in the old Mataró prison, it shows floor plans of spaces built to imprison people without charge from a World War I-era internment camp in Great Britain to the Moria refugee camp on Lesbos. The installation reflects Manifesta’s broader remit of framing engagements with European history with contemporary art, and helping audiences position themselves in relation to its social and political present. The impact of Domènec’s work is greatly enhanced by the space in which it is shown: Mataró was the first panopticon-style prison in Spain. Unfortunately, not every piece in this biennial is as substantial or shown in contexts as apt or as focused as this.

Manifesta’s fifteenth edition has been divided into three clusters—“Cure and Care,” “Imagining Futures,” and “Balancing Conflicts”—spread across twelve districts in the Barcelona metropolitan area. The narrative thread of the event itself is equally atomized and dispersed. Within the three clusters, viewers encounter works that do not connect with each other—but do, however, with the curatorial approach of …

September 18, 2024 – Review

Whitney Biennial Performance Program

Sanna Almajedi

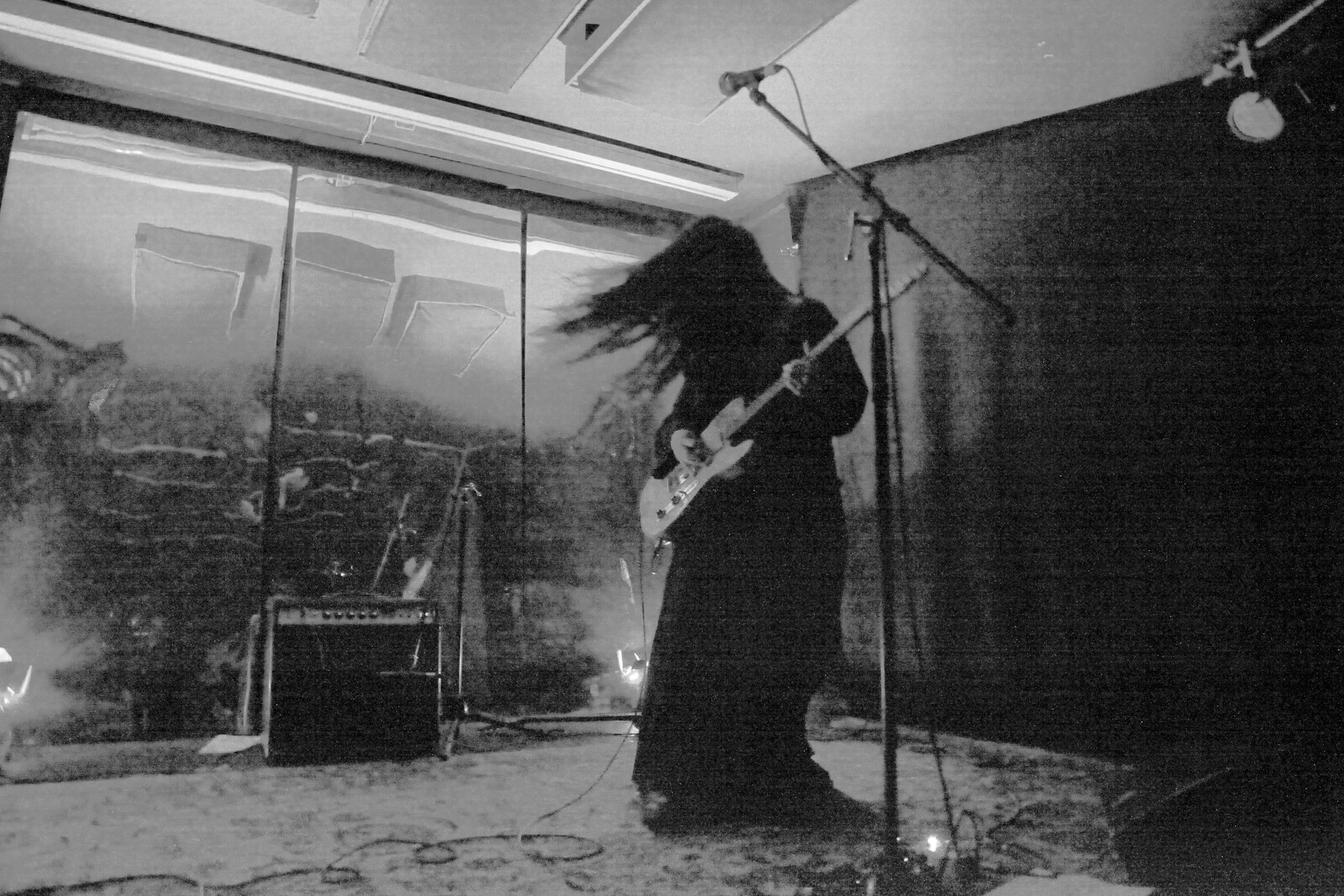

Taja Cheek—currently artistic director at Performance Space New York, and an artist in her own right as L’Rain—has long advocated for the inclusion of sound artists and musicians in the gallery space, as central figures rather than an entertainment vehicle to lure crowds. This year’s Whitney Biennial featured a five-part performance program, curated by Cheek, featuring an array of performances deeply rooted in sound. Artists Debit, Sarah Hennies, Holland Andrews, Alex Tatarsky, and JJJJJerome Ellis presented electronic music, improvised sounds, an experimental music ensemble, and a sonic exploration of language.

The program began with Debit, playing music from her album The Long Count (2022), which imagines the music of the Mayan civilization through a theatrical and fantastical three-act performance, using intense drone sounds and samples of precious and eerie wind instrumentation. The stage consisted of a mountain made out of a pile of dirt/wood, spot lights and a curtain that was lifted at the end of the show to unveil the Whitney’s majestic view of the Hudson River, alluding perhaps to a call for the land. Debit used synthesizers which, according to the press release, “have sampled and processed the sounds of Late Postclassic Maya wind instruments. Using tones from …

September 17, 2024 – Feature

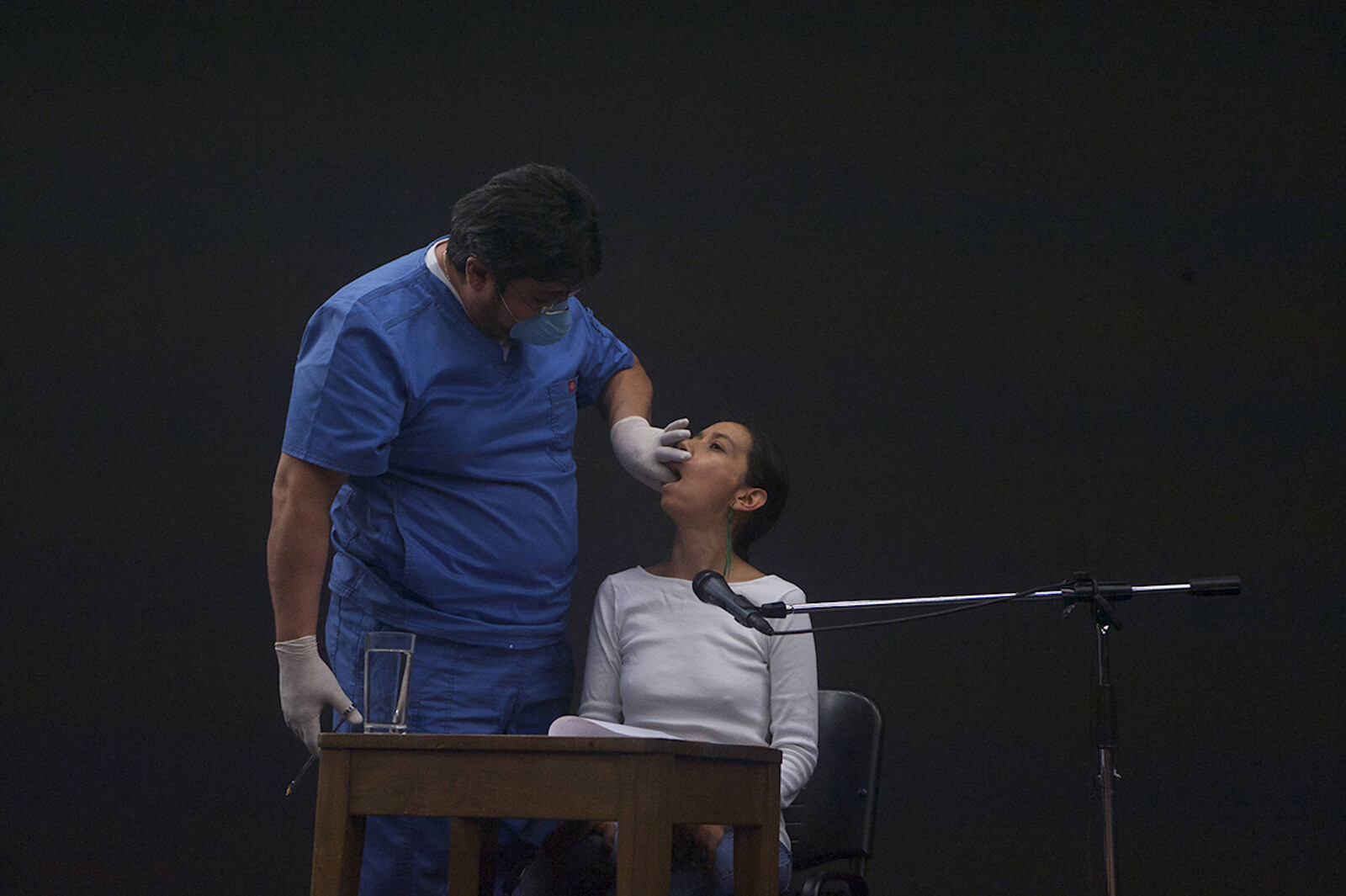

Pallavi Paul

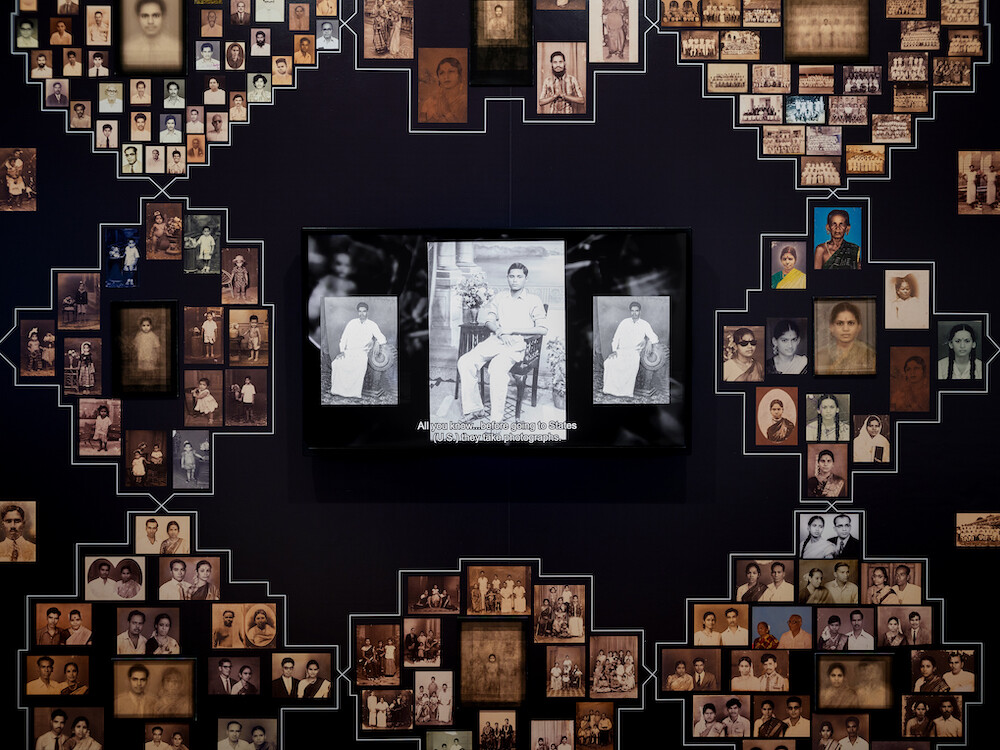

Pramodha Weerasekera

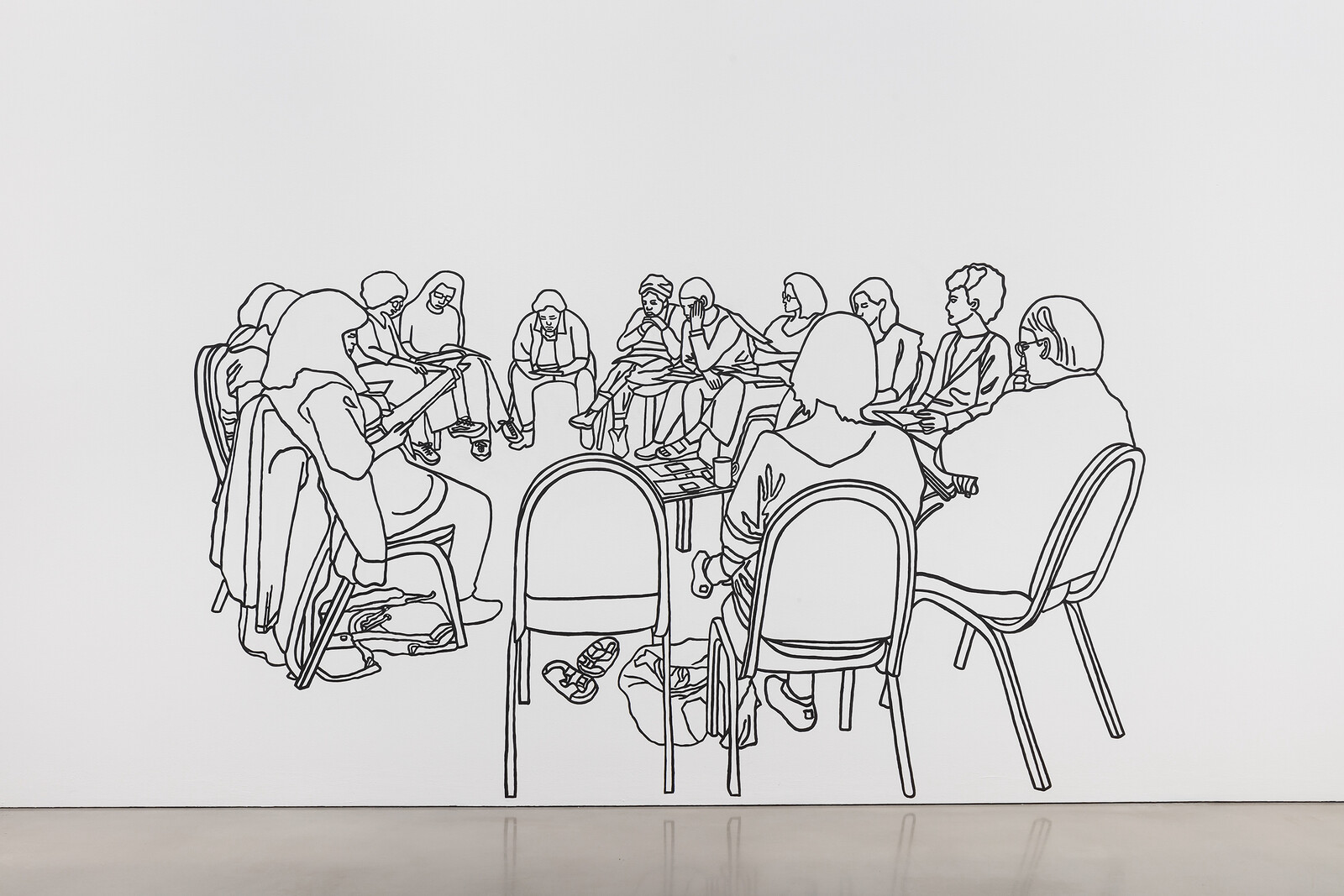

Pallavi Paul pursues a single goal across diverse disciplines: to make visible that which cannot normally be seen. Between 2013 and 2022, her works took inspiration from topics including India’s feminist movements (Long Hair, Short Ideas, 2014), the children abducted to fill arrest quotas for juvenile delinquency in the late 1970s (The Blind Rabbit, 2021), and the 2019 discriminatory citizenship law which precludes the naturalization of Muslims fleeing from Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Bangladesh due to fear of religious persecution in their home countries (in Far Too Close, 2020). Made between Paul’s bases in Delhi and Berlin, these multimedia installations, participatory performances, photographs, texts, and watercolors touch on concepts such as breath, grief, death, secrets, disappearance, reverie, and injustice.

In doing so they call to mind Ann Cvetkovich’s concept of an “unusual archive,” proposed as a solution to the un-representability of trauma and related emotions of love, rage, grief, and shame. Cvetkovich conceives of this archive as ephemeral, consisting of oral and video testimonies, memoirs, letters, journals, and more, just as Paul’s work over the past decade draws on both individual and collective memories. The artist’s choice to record and present people’s daily lives negotiates alternative approaches to documentation, media, and …

September 13, 2024 – Review

“brecht: fragments”

Isobel Harbison

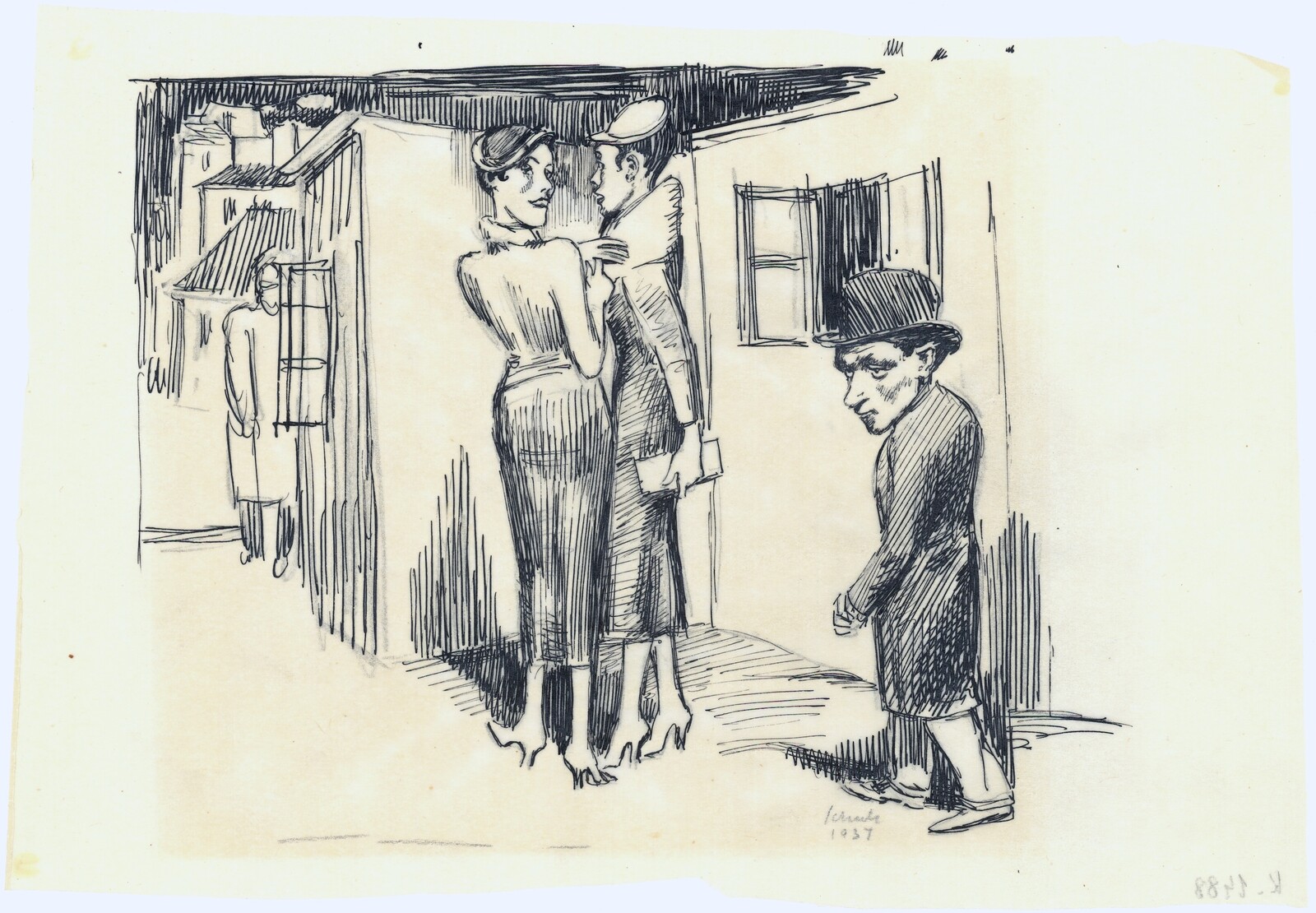

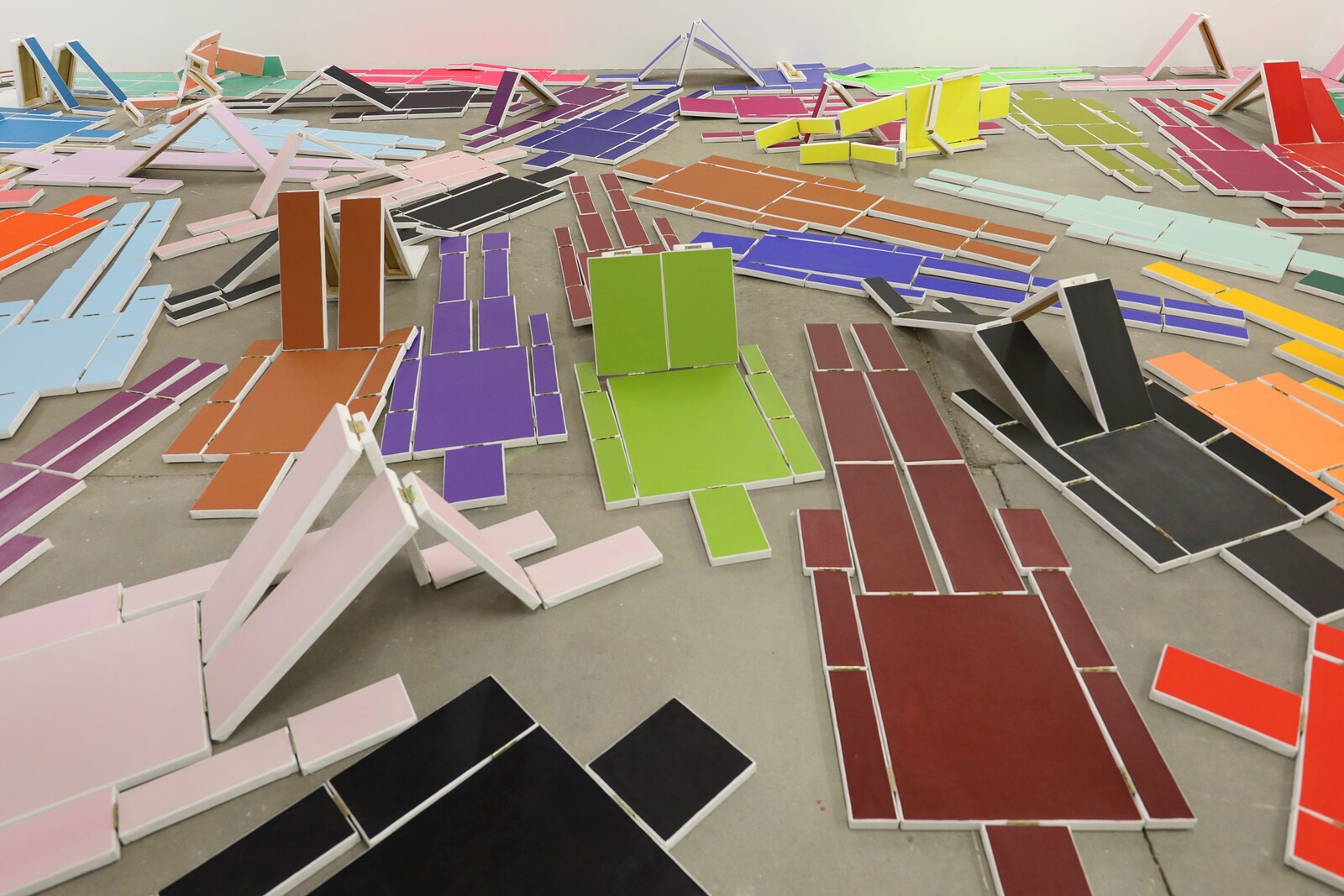

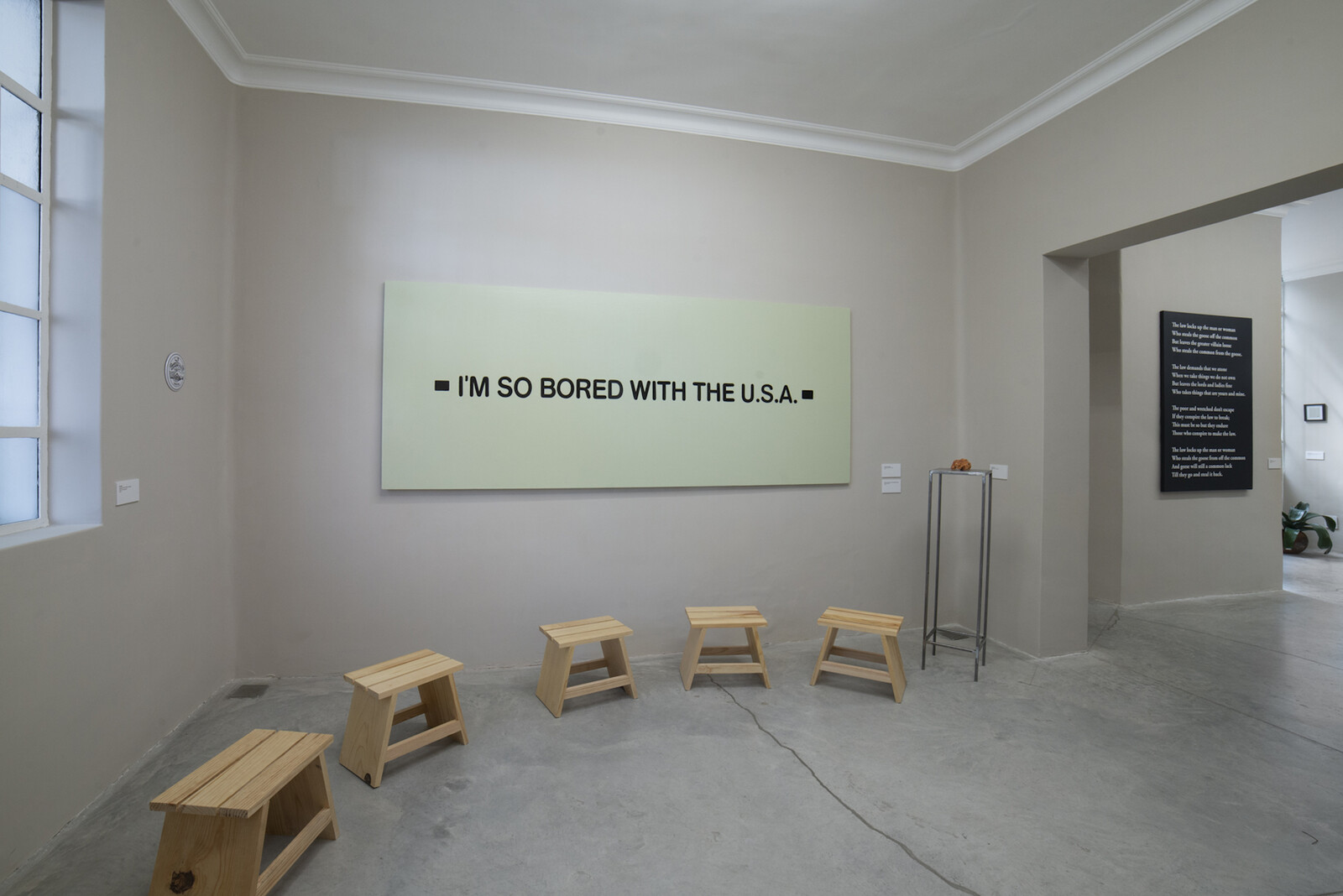

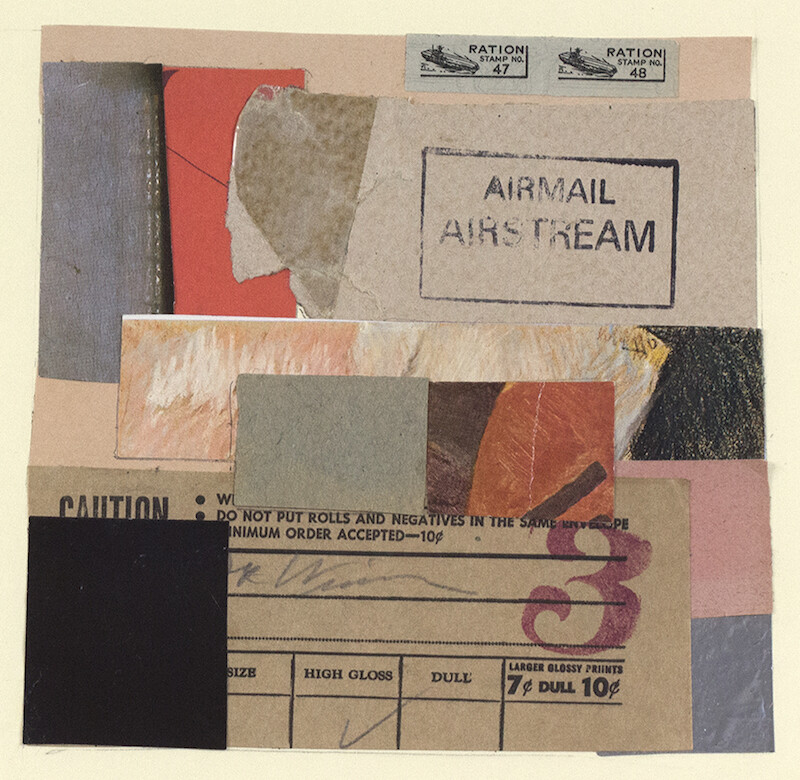

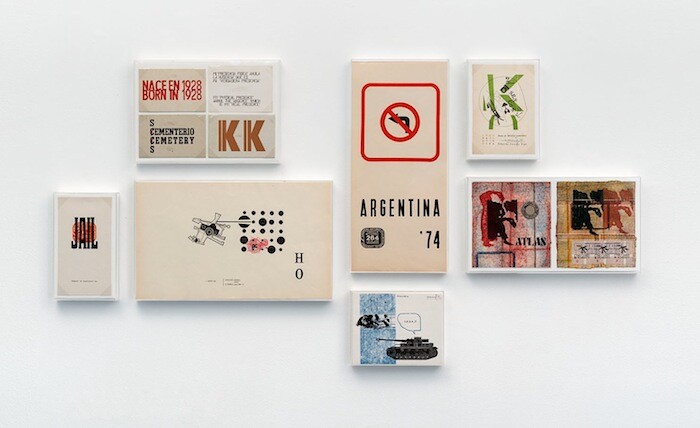

If each generation gets the drug it deserves, it also deals its own communicative form. Ours is the generation of the fragment, the snapshot, the caption, the info-bite: dulled post-digital distortions of the pictorial and literary chop-ups that appeared in the interwar years, via George Grosz, Hannah Hoch, and Walter Benjamin. Bertolt Brecht explored the form in a dramaturgy that poked at a public unresponsive to the rise of totalitarianism. Featuring material that is now a century old, “brecht: fragments” provides a masterclass for understanding how cropped photographs and scraps of text might amount to more than social media gruel and instead, artfully combined, result in riotous dramatic forms, crisp counterpropaganda, and pertinent anti-capitalist critique.

The exhibition is divided into two parts. The first includes a selection of paper elements from the Bertolt Brecht Archive (of its total of 200,000 folios) at the Akademie der Künste, Berlin, displayed in climate-controlled vitrines or copied and pasted across the walls and other props. A set of never-displayed collages (BBA 1198, 1941-47) shows how Brecht clipped original German press photographs and stuck them to paper in pairs and trios to explore images of social formations, urban gatherings, couplings and trysts, and the male …

September 12, 2024 – Review

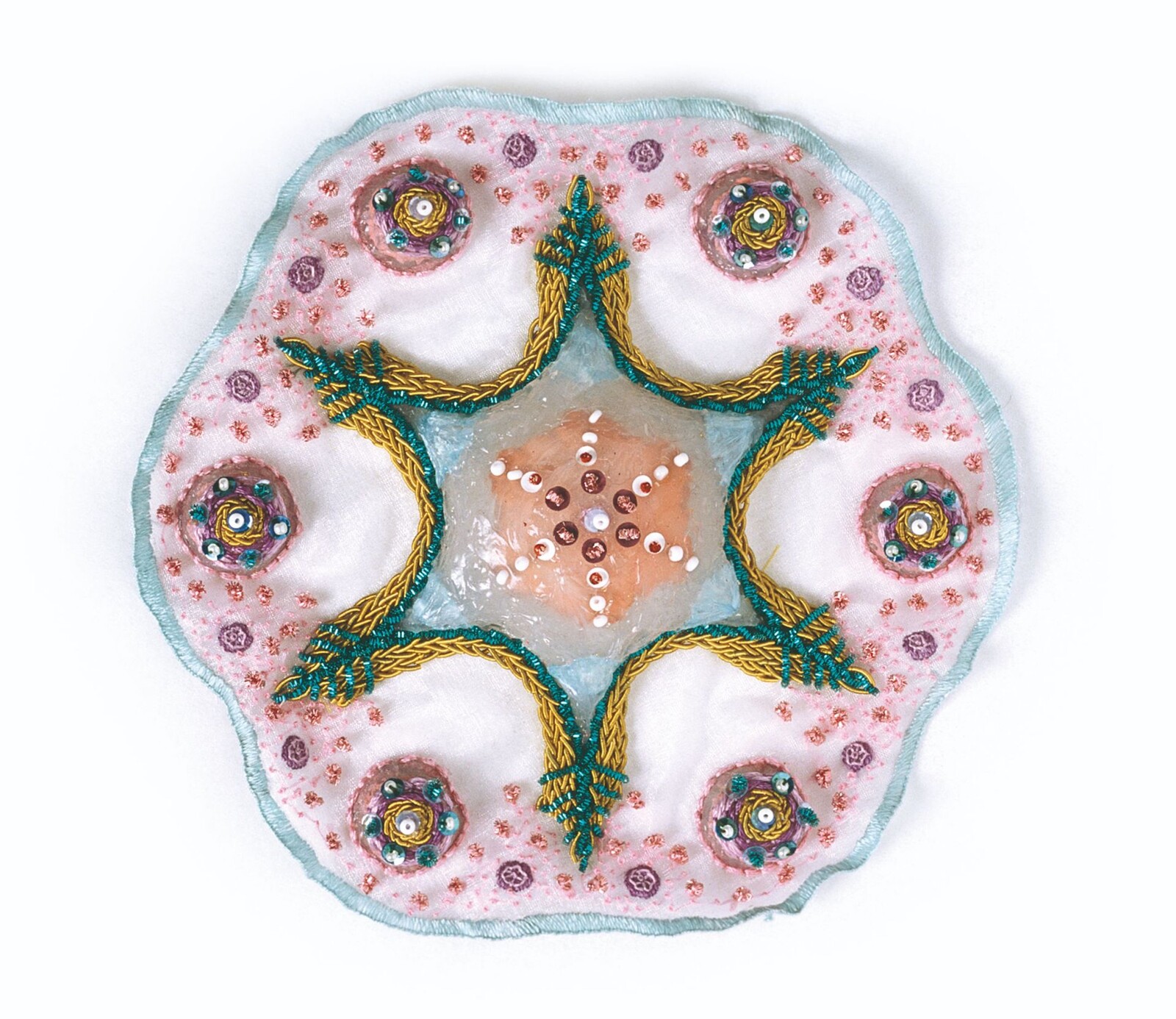

David Medalla’s “In Conversation with the Cosmos”

Debra Lennard

In David Medalla’s kinetic, adventuresome world, the smallest of gestures can have far-reaching effects. So goes the origin story of his well-known work, A Stitch in Time, first initiated in 1968. The artist had arranged to meet two of his former lovers, who were passing through London, at Heathrow airport, where he gifted them each a handkerchief, needle, and thread, to help them alleviate the tedium of transit. Years later, in Schiphol airport, he saw a handsome young backpacker shouldering an unusual-looking object: a hefty roll of patchworked fabric, studded with adornments. At the base of the patchwork, in Medalla’s raconteur telling, was one of the original, gifted handkerchiefs. Off went the backpacker and, with him, the fabric creation. After that, Medalla said, “I started to make different versions of A Stitch in Time in different places.”

A Stitch in Time—a participatory artwork, typically displayed as a long sheet of cotton onto which audiences are invited to sew whatever they choose, using thread provided—is at the Hammer Museum in archival form only: Medalla’s handwritten account of the work’s origin and list of its installations from 1968 onward, together with two small boxes of thread used in previous displays. It’s an …

September 10, 2024 – Review

“Crip Arte Spazio: The Disability Arts Movement in Venice”

Kenny Fries

The past few years have seen more disability-themed art exhibitions staged worldwide. The majority of these exhibitions, most notably “Crip Time” (Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt am Main), included both disabled and non-disabled artists and were curated by non-disabled curators, resulting in a medicalized focus with a lack of historical context. It seems a recent emphasis on exhibits focusing on “the body,” first prompted by an academic interest in transhumanism, and then perhaps primed by Covid-19, have led to a co-opting, of sorts, of disability for disability or disability-adjacent exhibitions.

Now, “Crip Arte Spazio: The Disability Arts Movement in Venice“ changes this trajectory. The exhibit focuses on the UK Disability Arts Movement (DAM)—its history and its contemporary progeny. The exhibit is curated by David Hevey, the CEO of Shape Arts, the UK disability-led arts organization and producer of “DAM in Venice.”

This transformation of perspective is clear even before entering the exhibit. Parked outside—and lifted front first to a forty-five degree angle—is Gold Lamé (2014), sculptor Tony Heaton’s refashioned National Health Service (NHS) Invacar. Heaton, perhaps the best known of the DAM artists, encases in gold what was a blue vehicle given by the state health service to disabled drivers, …

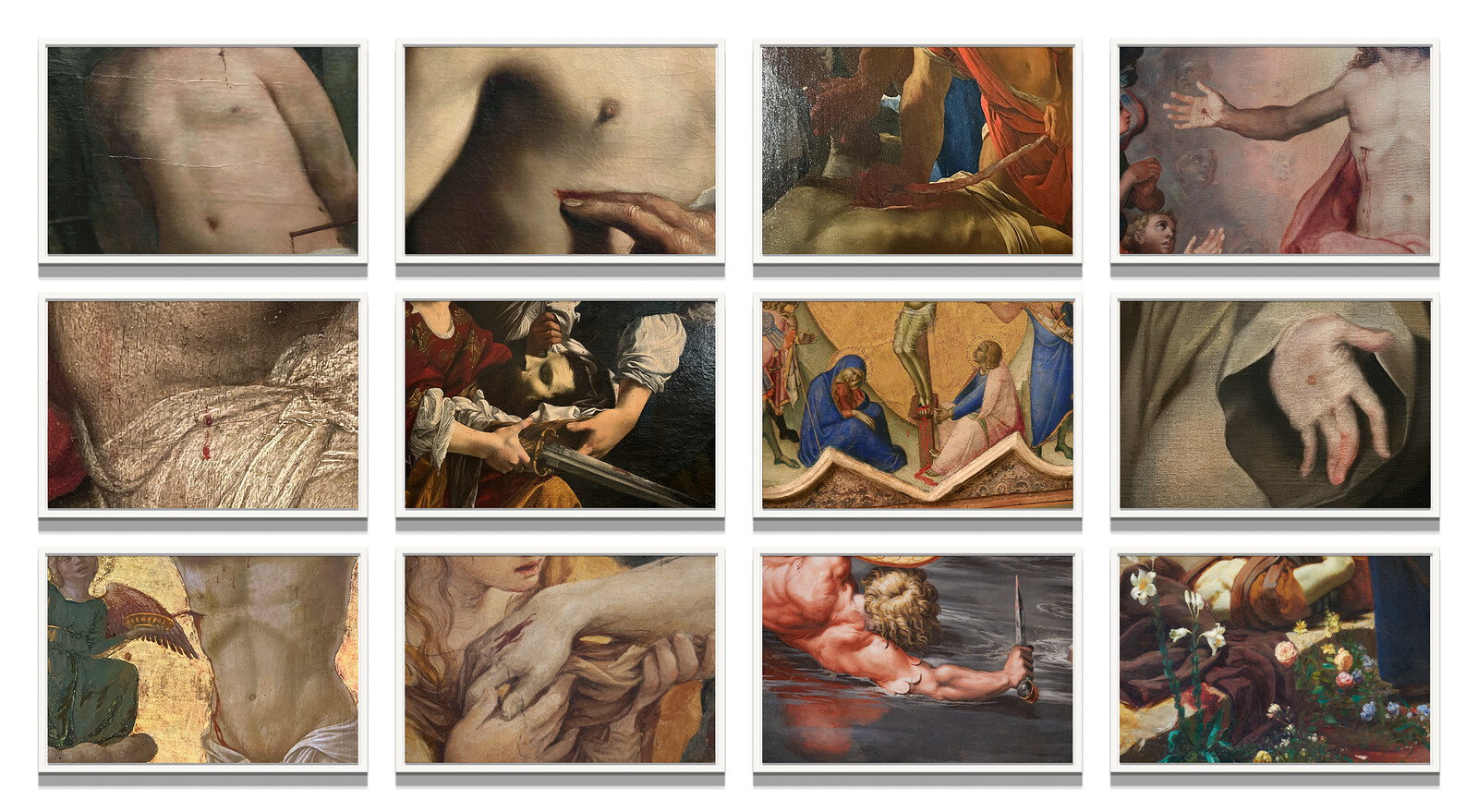

September 6, 2024 – Review

Harun Farocki’s “Inextinguishable Fire”

Leo Goldsmith

Greene Naftali’s new exhibition of works by Harun Farocki derives its title from perhaps the German filmmaker’s most famous work, a gently excoriating and laser-sharp 1969 film about the complicity shared amongst politicians, Dow Chemical executives, and ordinary workers in the production of the chemical weapon napalm. Inextinguishable Fire remains utterly devastating, a frightening but cogent delineation of the phases of dissociation we experience as we gaze at media images of atrocity, and a methodical examination of how the abstraction of labor makes us unconscious of our complicity in the violence of war.

Here, however, the specificity of Farocki’s title is, along with its definite article, lost. This lends it a more nebulous quality. Perhaps the “inextinguishable fire” in question refers not to a chemical weapon, the slightest drop of which—the film’s voiceover narration tells us—burns for half an hour at a temperature of 3,000 degrees Celsius. In the context of a show that marks a decade since the filmmaker’s death, the title almost sounds like a tone-deaf tribute to Farocki’s burning legacy. It loses its precision as a catch-all for a group of works that branches two different phases of the filmmaker’s career (the 1960s and the 2000s) and …

September 4, 2024 – Editorial

For context

The Editors

I have spent the past few days conducting studio visits in a city foreign to me. Encountering works of art in the context of their production—and seeing how they are informed by factors ranging from the architecture of the building to the character of the neighborhood—throws them into striking new relief. As does hearing artists talk personally about their practice and the lived experience from which it emerged. Their work is couched in situations that make it more easily legible, even (perhaps especially) if it rebels against the social, historical, or political milieux in which it is made.

The removal of the work from the studio also removes it from the networks of relation that might lend it meaning. Anyone who has witnessed the transformation of an object that has been kicked around a studio for two years into something to be handled with kid gloves when it leaves for the gallery will be sympathetic to the idea that it is precisely this abstraction from contexts that establishes the object as a “work of art,” with all of the implications of value and status connoted by the term. It is by entry into the immaculate space of the white cube, …

August 1, 2024 – Feature

Futuredays

The Editors

Archival documents “are not items of a completed past, but rather active elements of a present,” writes Ariella Azoulay. As e-flux Criticism takes a break from publishing new material in August, the editors have selected a few pieces from our free-to-access archive of more than 1,700 articles that might relate in new and unexpected ways to the moment. Search the archive yourself by clicking here.

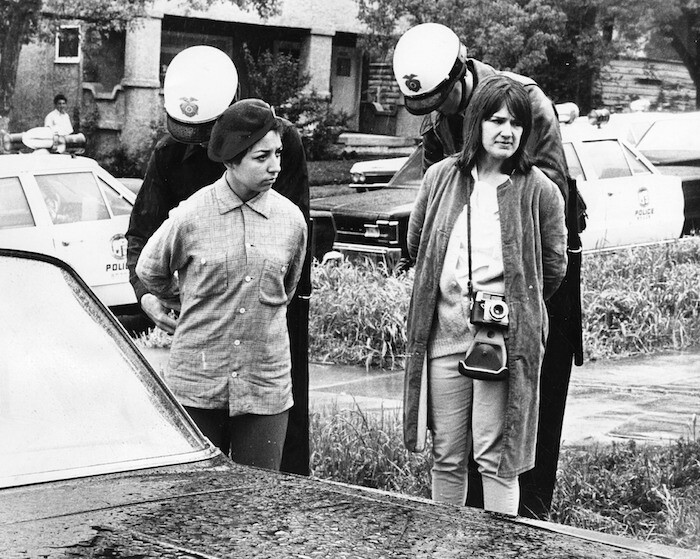

“Defiant Muses: Delphine Seyrig and the Feminist Video Collectives in France in the 1970s and 1980s” by Barbara Casavecchia

Moving behind the camera was for actress and activist Delphine Seyrig “a revelation, an enormous pleasure, an incomparable revenge,” writes Barbara Casavecchia in her review of this 2019 exhibition at the Reina Sofia in Madrid. Showing how feminist collectives in France took inspiration from the revolutionary postcolonial filmmakers of the Global South, the show challenges the model of vanguard art beginning in the west and being adapted elsewhere to local conditions. Here as throughout the history of modern and contemporary art, the opposite is true: the example of the “margins” electrifies a moribund “center.”

LaToya Ruby Frazier: The Last Cruze by R.H. Lossin

LaToya Ruby Frazier’s “The Last Cruze” documented the fate of laborers at a GM …

July 31, 2024 – Feature

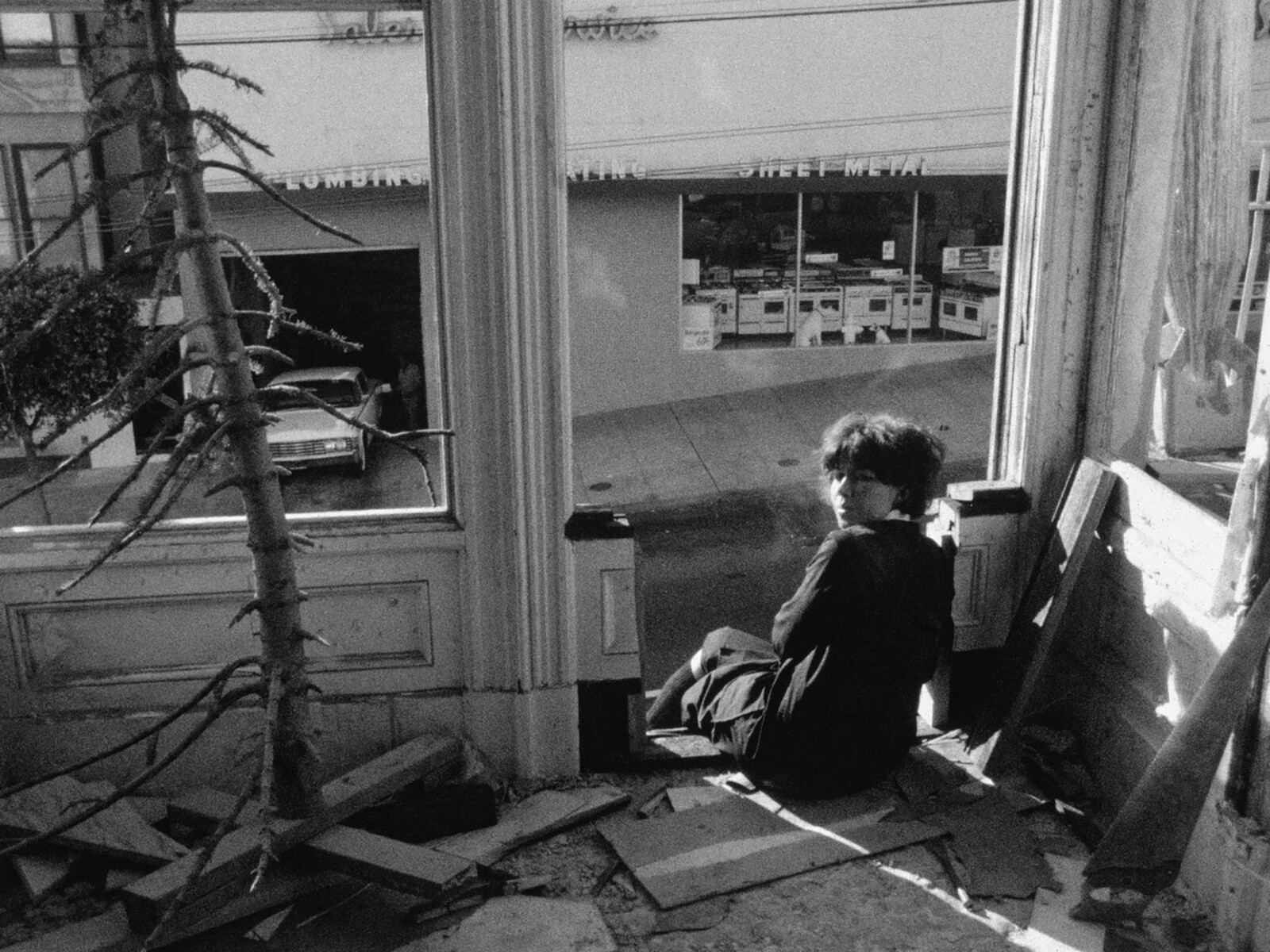

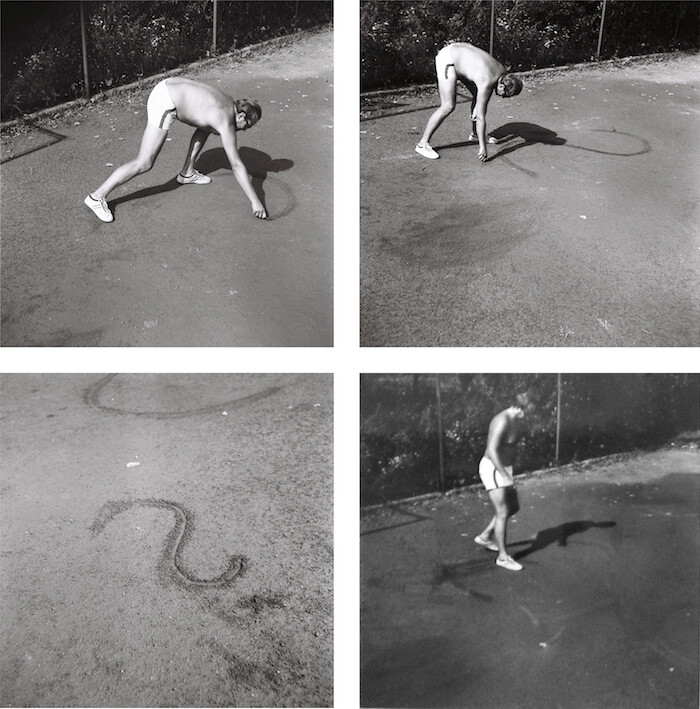

Mo Yi’s Selected Photographs, 1988–2003

Patrick Langley

The photographer Mo Yi describes himself as “a stray dog.” It’s a useful metaphor for understanding both his peripatetic life and his restless approach to street photography. The images collected in his first monograph to appear in English—published to coincide with exhibitions at Beijing’s UCCA and Rencontres d’Arles curated by Holly Roussell, who edits the book and contributes the first of two essays—are the result of his rigorous commitment to chance.

As Christoph Wiesner notes in the second essay, Yi’s photographs of urban life, captured mostly outside and on the move, were inspired in part by Jackson Pollock’s action painting. He took these pictures not just intuitively but almost at random, moving the camera, his body, or both, sometimes mounted on his arm or hung around his neck, and often without looking through the viewfinder first. The mostly black-and-white photographs that result are as blurry, claustrophobic, and raw as you’d expect. They suggest the adrenalized mood of a country disoriented by breakneck change and uneasy about the relationship between the individual and the collective.

The series that opens the book, “1m—The Scenery Behind Me” (1988–89), features a handful of proto-selfies. Yi’s scrunched frown or truncated forehead appears at the bottom …

July 29, 2024 – Review

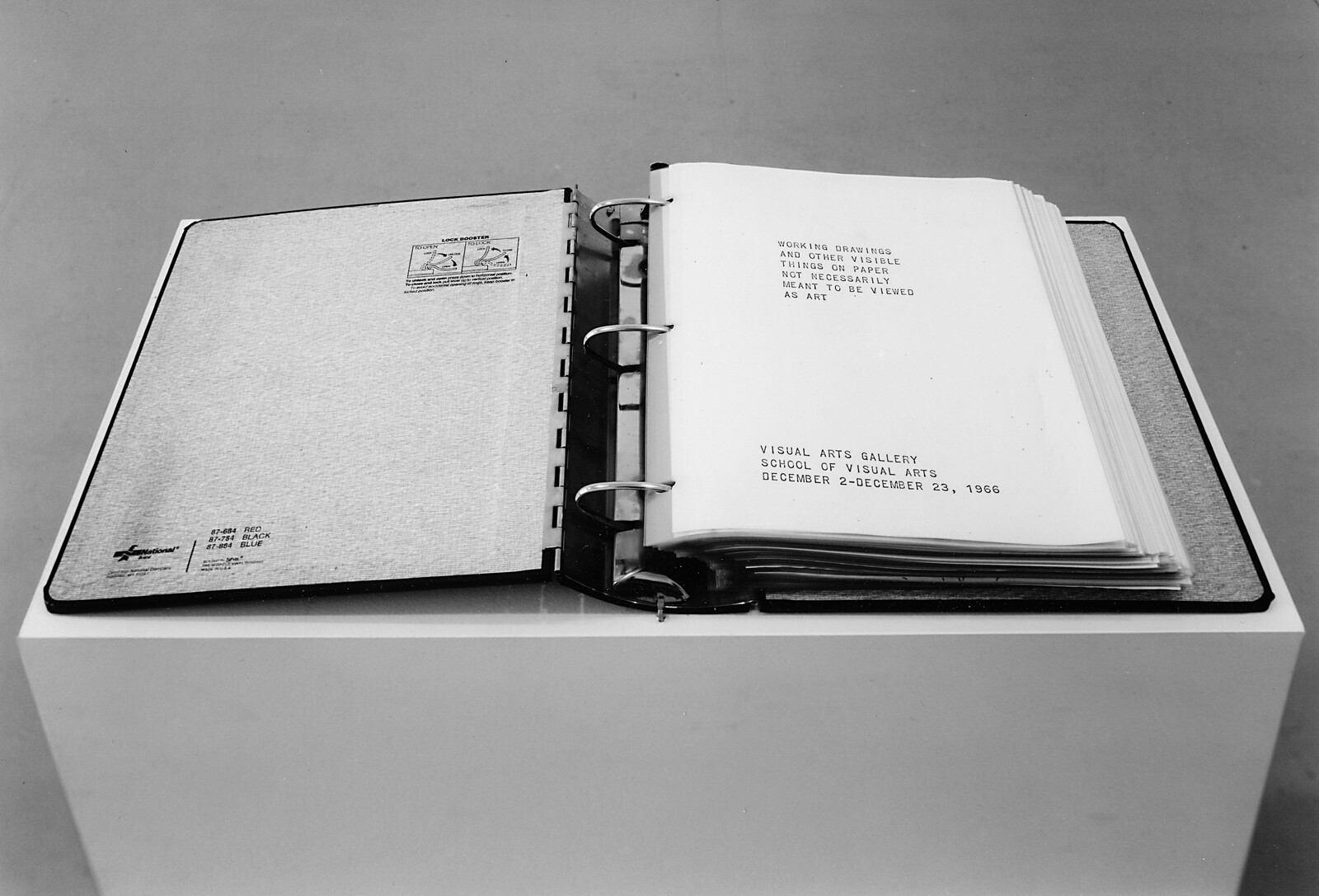

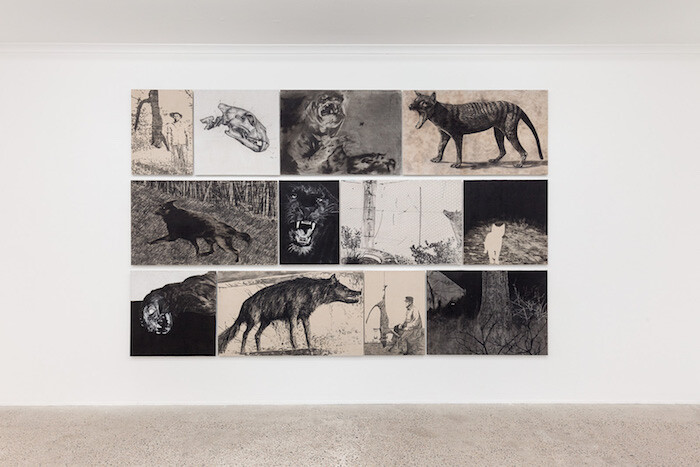

“Multiple Realities: Experimental Art in the Eastern Bloc, 1960s–1980s”

Ksenya Gurshtein

Walking through this exhibition of some 250 works by nearly a hundred artists working in the former Eastern Bloc, I was forced at one point to turn back and re-enter it through the exit so that a mess left by a “service” dog could be cleaned up. Doubling back to go forward was an apt metaphor, I thought, for the frequent adjustments to circumstances that these artists working either unofficially or within the “second public sphere” had to perform throughout the period covered by this major historical overview.

Indeed, one of the biggest accomplishments of a show covering six former countries that constitute nine present-day ones (Poland, Romania, Hungary, the former East Germany, Czechoslovakia, and Yugoslavia) is that it conveys the complex lived reality of artists who, while making work for the same multifaceted reasons as their peers elsewhere in the world, were constrained by various degrees of state hostility during a series of asynchronous national “thaws” and “freezes” imposed by the Soviet “brother.”

The exhibition is noteworthy for how much it tries to accomplish and the possibilities for discovery it offers, with works ranging from heartbreaking to whimsical. Organized into four large sections, it covers the themes of “Public …

July 26, 2024 – Review

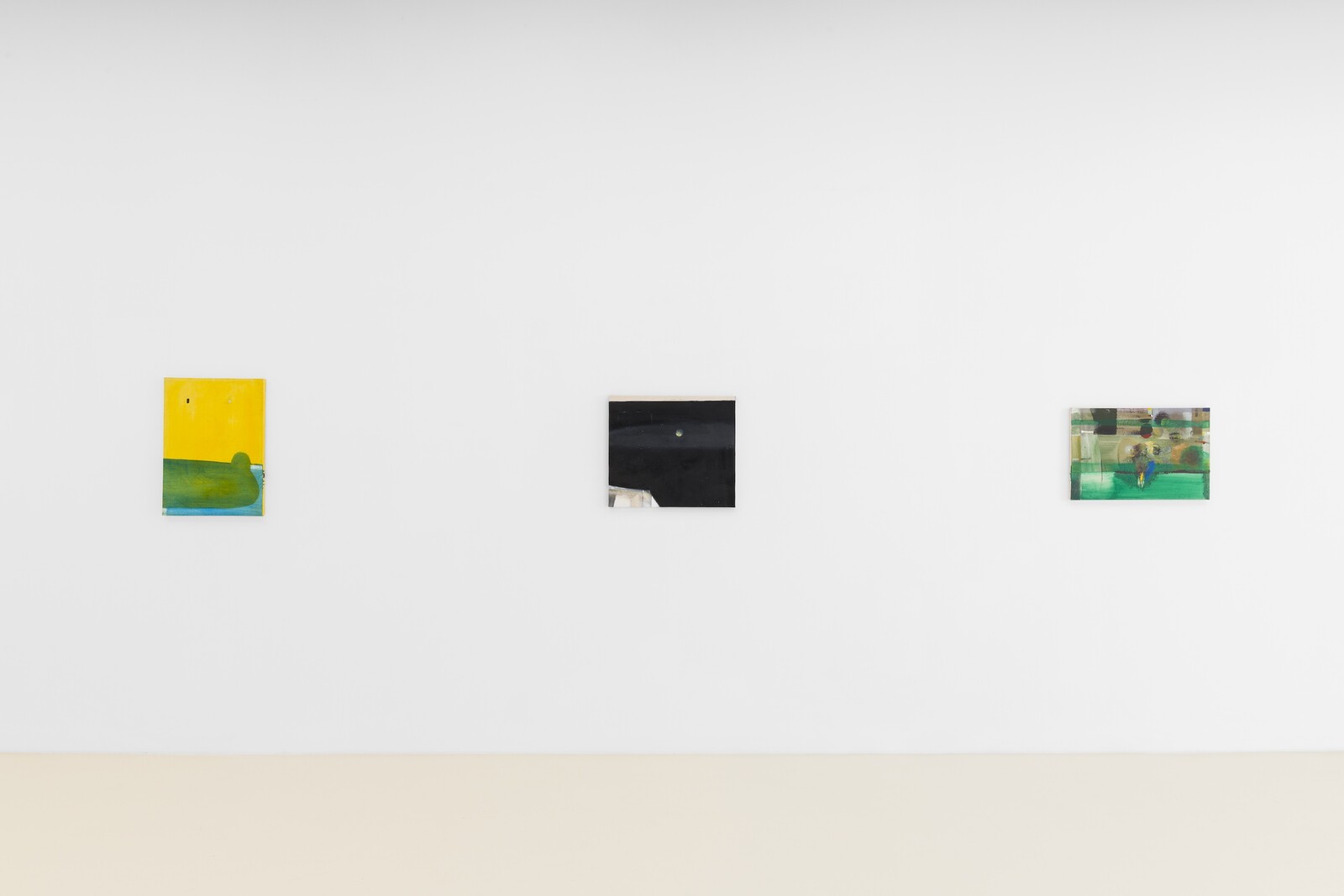

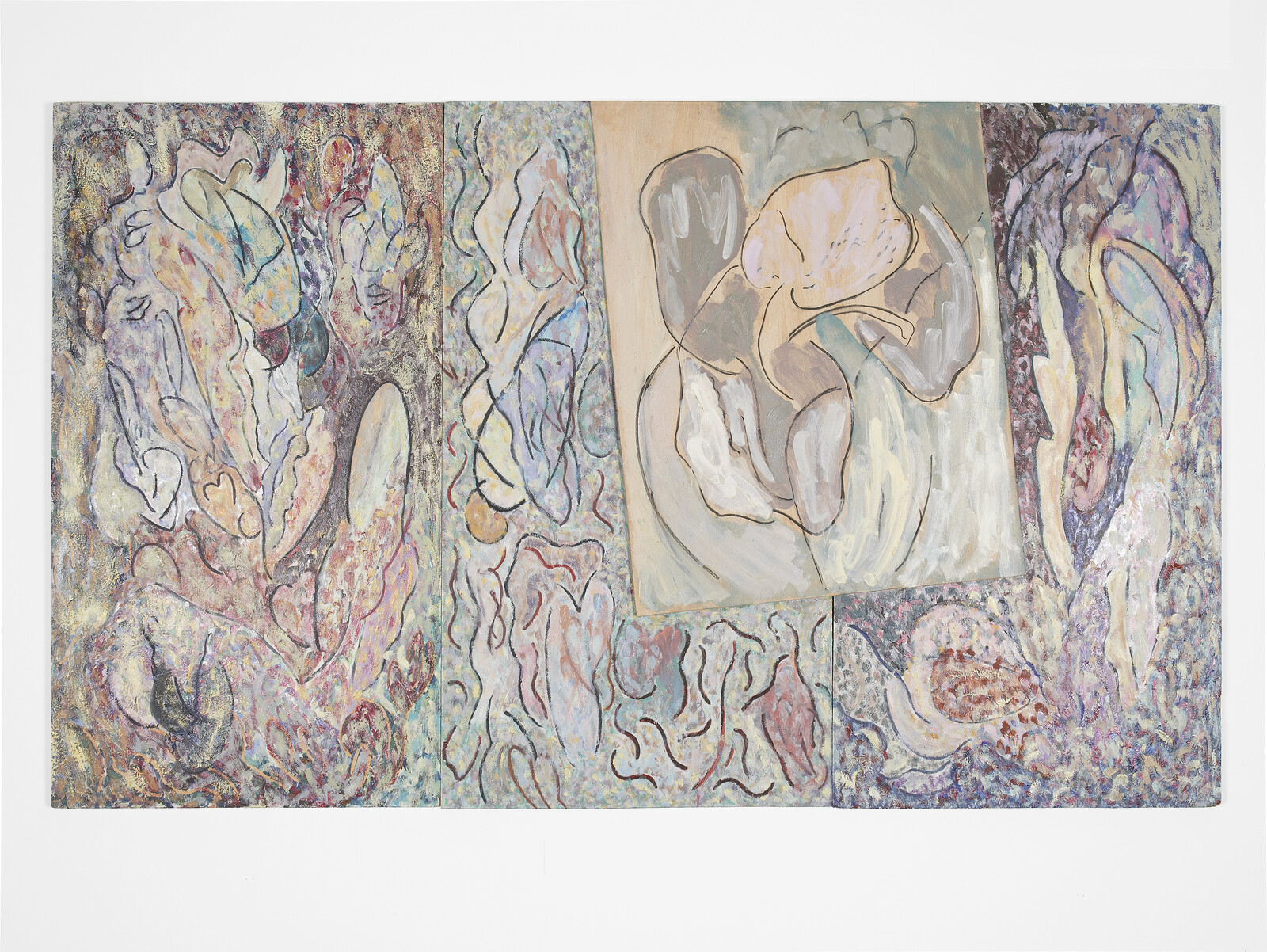

Caragh Thuring

Fanny Singer

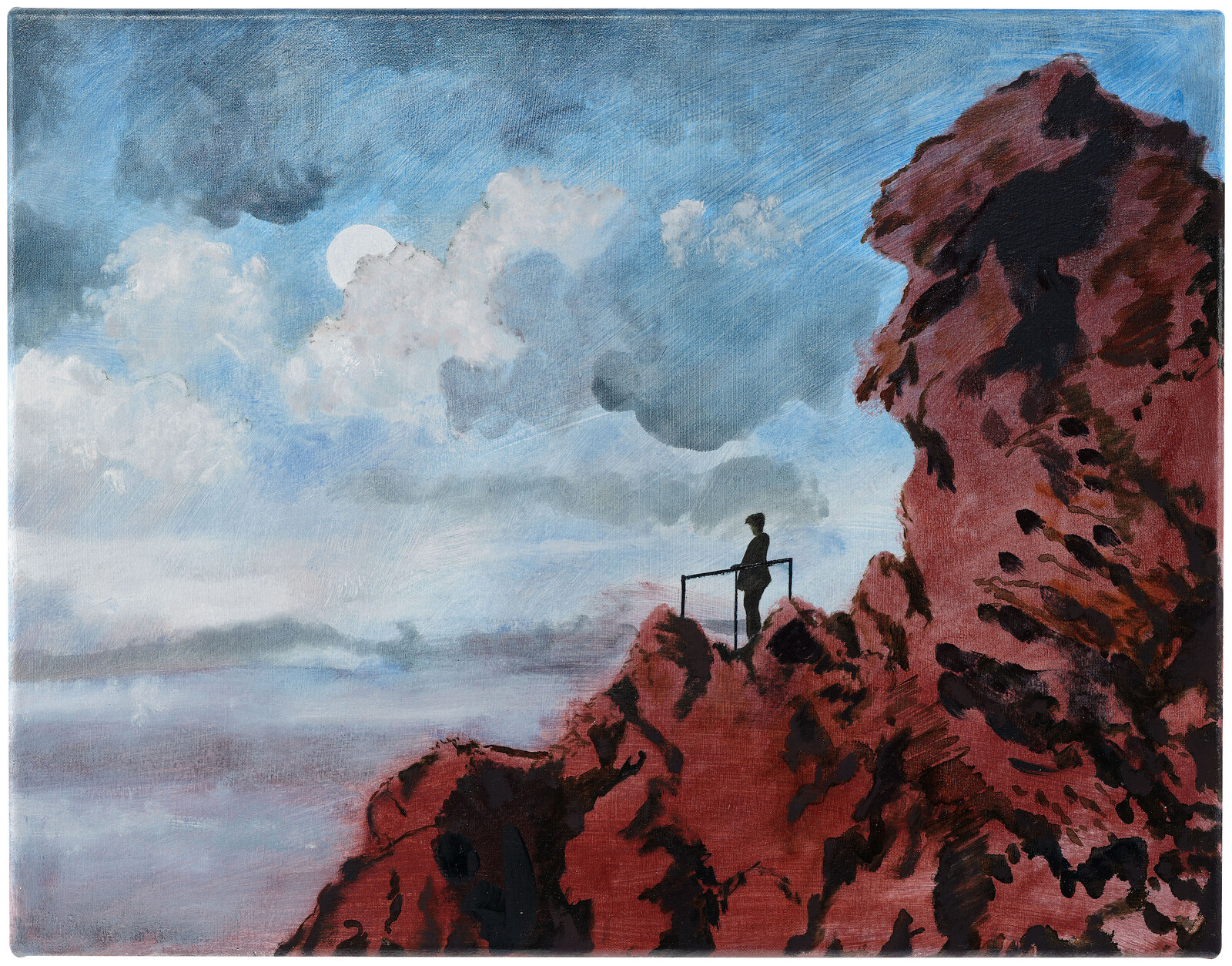

As a kid growing up in Berkeley, I oriented myself by the silhouette of Mount Tamalpais, crisscrossed its slopes on foot in every season, even touched fingers to a rare flocking of snow at its peak. That an artist living 5,500 miles away might pay homage to this local landmark without ever having seen it in person—as the London-based painter Caragh Thuring has done—was a compellingly fantastical proposition.

My mind, of course, went to Etel Adnan, whose vivid, Platonic paintings of the mountain are among her most iconic. From the time the Lebanese-American artist and writer moved to Sausalito in the late 1970s—where it was in plain and constant view—and well after her move to Paris in later years, Adnan painted hundreds of views of Mount Tamalpais, which she described as “the very center of my being.” You cannot look at Thuring’s string of small canvases (smaller than she has worked on for years), and not think of Adnan’s intimate, lapidary portraits of the same landmark.

Yet Thuring swiftly and assertively makes the subject her own. The painting opening the exhibition, Given Enough Goading (all works 2024), transforms Mount Tamalpais into one of the artist’s recurring subjects: a volcano, replete …

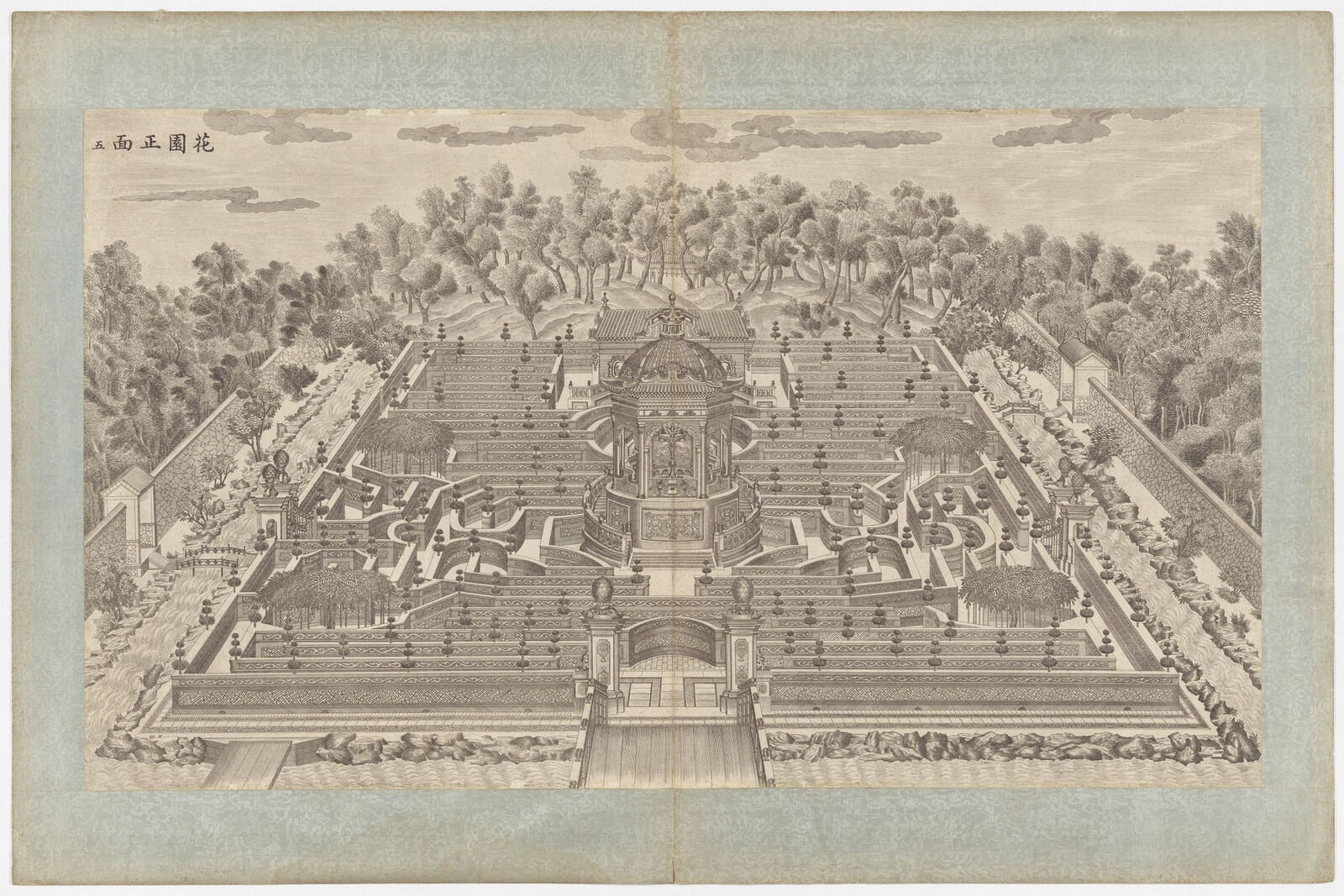

July 25, 2024 – Review

Truong Cong Tung’s “The Disoriented Garden… A Breath of Dream”

Max Crosbie-Jones

Across the highlands of Vietnam, gourds have stored water, made music, and inspired legends for centuries. In his travelling solo show, Truong Cong Tung finds yet another use for these sinuous plants. The state of absence… Voice from outside (2020–ongoing) is an installation of soil boxes upon which dried, lacquered gourds of miscellaneous shapes and sizes appear to pump liquid through tangles of clear PVC piping. The illusion created by these crudely networked calabashes, a few of which overflow with seeds, burbling fluid or slowly expanding plumes of iridescent foam, is of a brittle, delicately balanced biosphere or microcosmos. Listening to its clicks and murmurs, I sense it’s one that is operational yet tilting towards decline: the larger of Jim Thompson Art Center’s two galleries also houses a video-projection screen wreathed with foraged detritus (twigs, a satellite dish, lengths of gauzy fabric, curtains of threaded wood beads, et cetera). Meanwhile, a dusky ochre glow and strong shadows evoke a state of autumnal decay.

Born in 1986, Tung majored in lacquer painting at Ho Chi Minh Fine Arts University but has since turned his attention to multidisciplinary work—sculptures and videos predominantly—centered on the morphing ecology, beliefs, and mythology of the Central …

July 24, 2024 – Review

Jonas Mekas’s “Requiem”

Lukas Brasiskis

Flowers were important to Jonas Mekas throughout his life and work, serving as a recurrent visual and thematic motif. Starting from the early 1950s, after his arrival in New York, the great avant-garde filmmaker would record his daily life, later revisiting and editing it into cohesive yet nonlinear stories. Among the best-known of these films is Lost, Lost, Lost (1976), which contains a memorable scene in which the artist, referring to himself as a “monk of the order of cinema,” captures close-ups of a grassy field in the early dawn. This almost ritualistic act illustrates perfectly how Mekas connected to nature through the medium of film.

Not only did he credit his early mentor, Marie Menken, with teaching him how to film these delicate subjects (Menken’s 1957 Glimpse of the Garden uses rapid edits to capture their ephemeral beauty), but they are frequently referenced in his poetry: “Flowers die / and return to the earth, / with the same scent / touching faces,” he wrote in 1966. Given his lifelong fascination with the natural world, it seems appropriate that his final film Requiem (2019)— made when he was ninety-six, now installed in this deconsecrated seventeenth-century church—should be an observation and …

July 19, 2024 – Feature

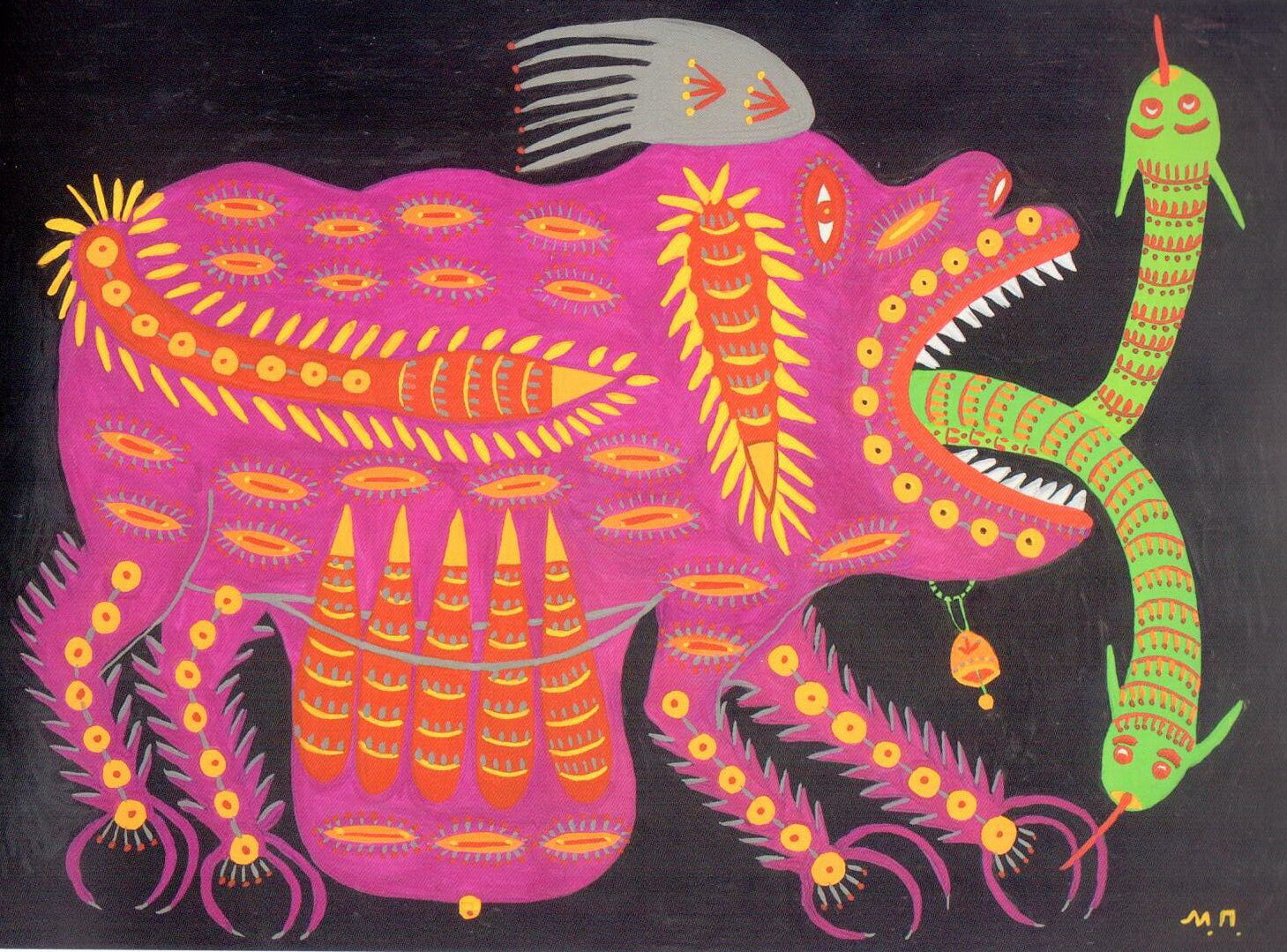

60th Venice Biennale, Central Asian Pavilions

Nikolay Smirnov

Between 2005 and 2013, the Central Asian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale presented work from the region. For the past two editions, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan have exhibited independently, which raises the question of what they hope to achieve. The Uzbekistan Pavilion is run by the state-funded Art and Culture Development Foundation, which is closely connected to President Shavkat Mirziyoyev through his daughter and official advisor Saida, who is known as the country’s image-maker. It has significant resources to “integrate the art of Uzbekistan into the global art and cultural space,” including by staging spectacular installations in a spacious pavilion at the heart of the Arsenale.

Compared to these soft power aspirations, the Kazakhstan Pavilion is a private initiative, if also closely linked to family networks, in this case between curator and artist. For the 2024 edition of the Biennale, Astana gallerist Danagul Tolepbay wanted to exhibit the works of her father, Yerbolat Tolepbay, one of the most famous “official” artists of his generation, in a parallel program. Being receptive to the idea, representatives of the Biennale communicated to her that no official submission for the national pavilion had yet been made. So she sought and received approval and some support …

July 18, 2024 – Review

Chantal Akerman’s “Travelling”

Max Levin

Chantal Akerman once told an interviewer that each of her films needs hallways, doors, and rooms. “Those doors and hallways help me frame things, and they also help me work with time.” Akerman’s first major retrospective in her native Brussels showcases the breadth of her time-based achievements across an art-deco labyrinth one could spend days within. The exhibition opens with digital restorations of four 8mm films submitted with Akerman’s 1967 application to art school. Projected alongside each other asynchronously, the silent snapshots drift between frenetic observation and acted scenes with Akerman’s mother and friends. These are the earliest examples of Akerman’s radical filmmaking that she would go on to call “documentary bordering on fiction.” A cinema of ethically crossing thresholds.

“Travelling” puns with the French travelling, or tracking shot. Akerman’s camera often moved right-to-left, working against the Hollywood standard of narrative progression and challenging preconceptions of what constitutes an advance. People are in transit in Akerman’s films, and the camera moves with them. Subjects exit train stations, check into hotels, ride the subway, and queue for buses. Les Rendez-vous D’Anna (1978), Akerman’s first film with major distribution, is almost entirely composed from travel passages. Not screened in …

July 18, 2024 – Review

Nina Sanadze

Lauren O’Neill-Butler

How should a monument be? Who deserves one? And who decides? One response pertinent to Nina Sanadze’s engrossing survey exhibition in her homebase of Melbourne occurred in January 2024, on the eve of Australia Day. Activists there removed a sculpture of Captain Cook and left behind the spray-painted words “The colony will fall” on the plinth. When authorities announced that the statue would be reinstated, the sense was of history reasserting itself. Sanadze’s show, which features installations and sculptures that repurpose fragments of historic statues, explores the way monuments—from sculptures to photographs—shore up particular versions of history, apparently doomed to reoccur.

Sanadze was born in Georgia’s capital, Tbilisi, in 1976, surrounded by large-scale public sculptures of Lenin. As a child she lived next door to the prominent Soviet sculptor Valentin Topuridze (1907–80) and remembers the enormous hands and head of Lenin scattered around his garden. “We kids would climb them,” she has said, adding, “all these figures would be overgrown with grapes, and it was really beautiful, that ruined aesthetic that’s sort of classical art, but not in its perfect museum form.” Many of Topuridze’s public monuments were destroyed after Georgia gained its independence from the Soviet Union in April …

July 11, 2024 – Review

Wu Tsang and Moved by the Motion’s Carmen

John Douglas Millar

Discussing her mode of collaboration, Wu Tsang has remarked that “I always feel the collaboration mandate is: if you’re going to do this, you have to fuck it up. You can’t do it respectfully, you have to almost disrespect it. You have to take it, change it, transform it, make it yours. Do to it what it does to you.” Strange then that Tsang and her collaborative band Moved by the Motion’s version of—intervention into, exploration through—Georges Bizet’s 1875 opera Carmen at the Royal Theatre Carré is so respectful at every level; benign, in fact, to the point of offensive.

There are two narrative lines: Bizet’s operatic rendering of the tragic story of the passionate Roma cigarette factory worker Carmen murdered by a former lover, the soldier Don José, after leaving him for a toreador is the first. The second follows a single-minded forensic archaeologist, played by Perle Palombe, in her attempt to have a Spanish Civil War grave opened. In this grave is said to be the body of the Red Paloma, a flamenco singer forced to perform in front of Franco before being executed. The archaeologist’s attempts are thwarted by a senior figure in the institution where she …

July 10, 2024 – Review

Gabriel Chaile’s “Los jóvenes olvidaron sus canciones o Tierra de Fuego”

Filipa Ramos

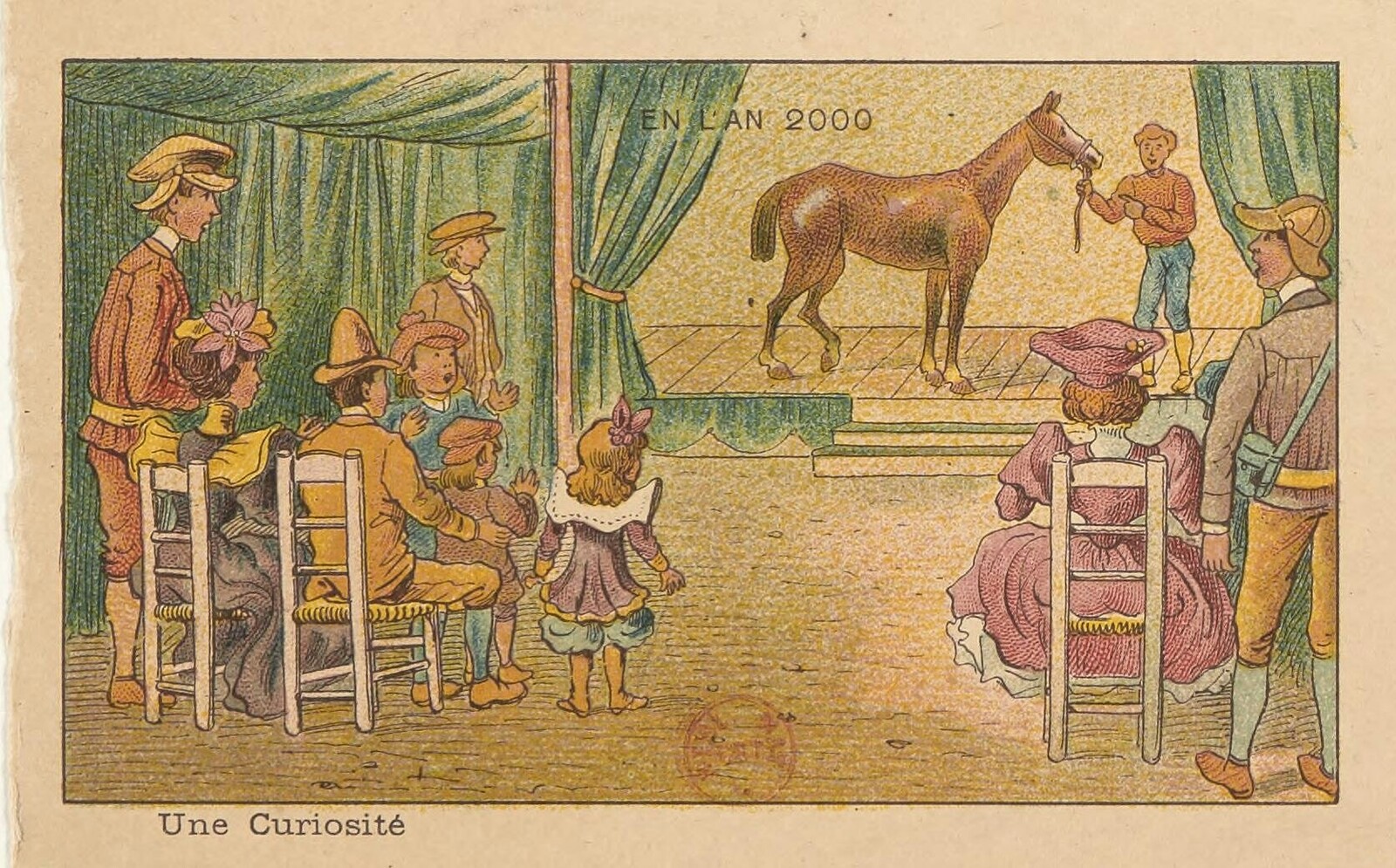

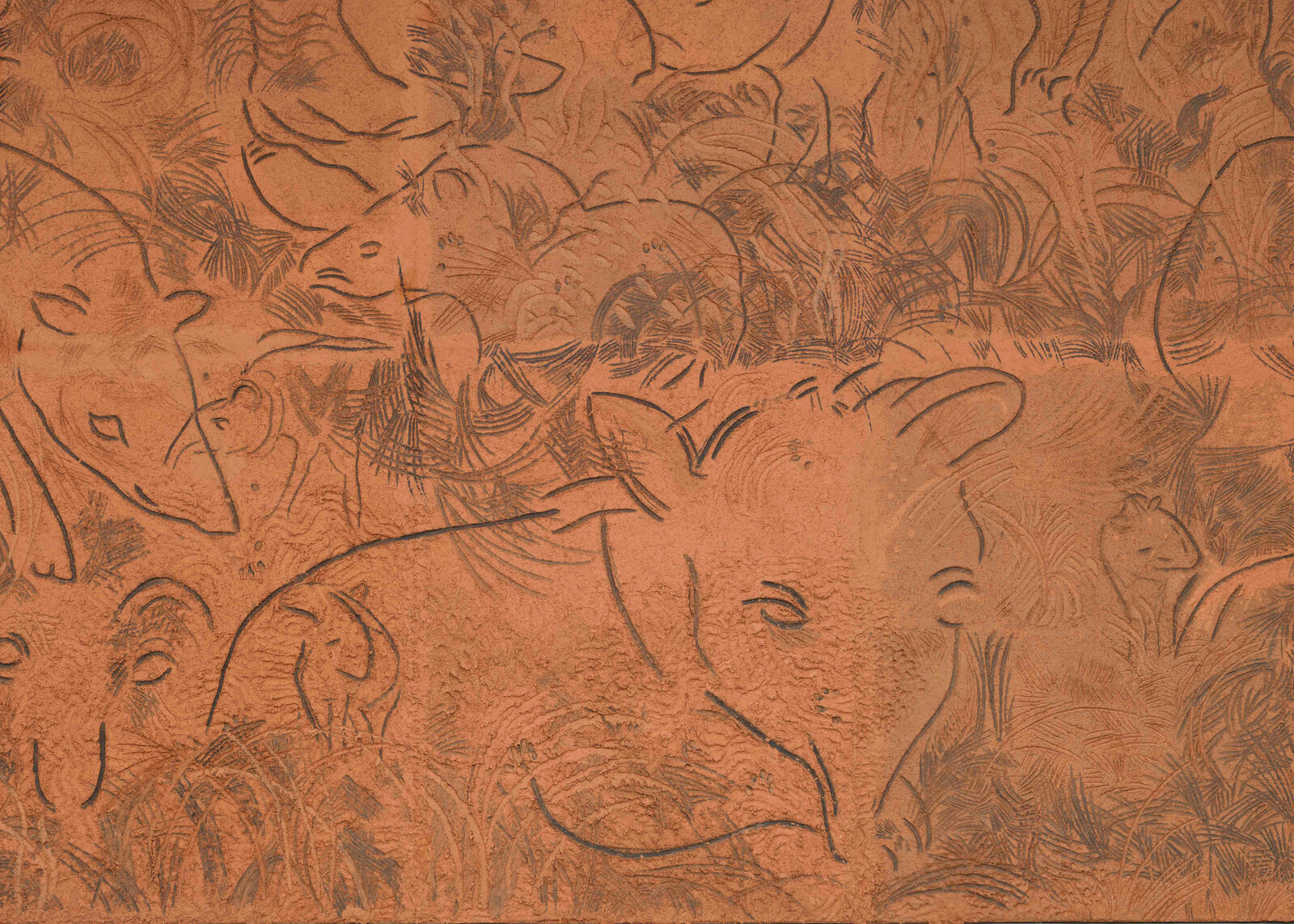

Humans became human by representing themselves and others. By painting images on cave walls of animals that mimicked those they chased, early humans produced the imaginaries and traditions that define us as a species. With their drawings, they invented past and future and connected memory to desire, remembrance to anticipation, trauma to anxiety. The images on those walls might be still, but the stories they told were in motion, animated by the light cast by flickering fires. As such, it could be said that the history of cinema predates written history. Cinema emerged from the animals whose images, engraved in their own blood and hair, expressed motion through time and space, and moved their audiences.

This awareness of the archaic nature of cinema, and its relationship to nature, is at the base of Gabriel Chaile’s memorable installation Selva Tucumana [Tucumán Jungle] (2024), which signals an important change in his artistic vocabulary away from the large-scale adobe figures for which he is best known. Born in San Miguel de Tucumán in 1985, the Lisbon-based artist has often sought inspiration in land and kin. His characteristic anthropomorphic sculptures—whose aesthetics echo the precolonial creations of his birthplace—are both private and public. Connected to …

July 8, 2024 – Review

Rossella Biscotti’s “Title One, I dreamt, Clara and other stories”

Sean O’Toole

The earliest work in Rossella Biscotti’s first institutional survey predates her training at the Naples Academy of Fine Arts by a decade. In 1991, when she was 12, the Vlora, a hijacked cargo ship carrying some twenty thousand Albanian refugees, unexpectedly docked in the Italian port city of Bari, near where Biscotti grew up. Many of the economic refugees were housed in a disused stadium. Skirmishes with Italian authorities ensued, resulting both in the refugees being repatriated and stricter border policies being implemented. A year later, Biscotti took a black-and-white photograph of the Adriatic Sea from Bari; using pen, she later superimposed onto this photo the outline of a hill, which she labeled “Albania,” also adding a fence, its central feature identified in Italian with the word cancello, or gate.

Displayed in the first of six rooms devoted to Biscotti’s thematically fluid and research-intensive work, this untitled photo highlights the importance of the sea in the artist’s work. Far from being a hackneyed subject, the sea emerges—episodically rather than serially—as a space that has enabled Biscotti to develop and refine her central artistic gesture: the recovery and visualization of “untold stories and unrepresented people”. Take Clara (2016), a sculptural installation …

July 4, 2024 – Review

Biennale Gherdëina 9, “The Parliament of Marmots”

Novuyo Moyo

The ninth Biennale Gherdëina takes its title from a Ladin myth that is, in part, a cautionary tale. It narrates the series of tragedies that follows when the Fanes—the indigenous people of the Dolomites—betray a pact with their animal allies, the marmots. The Kingdom of Fanes—a national epic that roams across Mediterranean, North Africa, and the Middle East—informs an exhibition that dwells on themes of interspecies relations, communal identity, and collaboration. As a place where people, cultures, and languages meet (German, Italian, and to a lesser extent, Ladin—the language of the Fanes—are used interchangeably), the Dolomite mountains on the border of Italy and Austria provide the ideal backdrop for these reflections.

In the darkened theater of Cësa di Ladins Museum, a bird’s song plays over speakers. Starting off with sweet melodious notes, Ruth Beraha’s Il cielo è deI violenti (The sky belongs to the violent, 2024) soon multiplies and swells, converging in discordant screeches that remind us that nature can be comforting and accommodating but also menacing and overwhelming—like the marmot, a cute-looking ground squirrel which has, reasonably, been described as “vicious.” The song loops back to the beginning, maintaining the tension between calm and panic. Beraha picks up the …

July 3, 2024 – Editorial

Obstructions

The Editors

Once a week I stand in front of a work of art in order to write about it. This exercise, designed to keep my eye in, has certain constraints. The text must be written in the presence of the work, in a single sitting, and without recourse to external resources. Not the least consequence of this workout has been the revelation of my own ignorance when denied access to online dictionaries (what is it called again when you scratch marks into oil paint?). But the most relevant here is how difficult it is for any visitor to spend a long time looking at things in exhibition spaces: I am endlessly being told by invigilators to keep moving, to get up from the floor, to stop obstructing the flow.

Last week, for instance, I visited another of those group shows dedicated to queering an abstract noun. The final room contained a standing speaker playing spoken word and music, an incense burner, and a dozen books of theory arranged as if to be read. The intention, it seemed, was to create an environment for self-education and reflection, and so I took a seat on the ledge running around the room’s perimeter. …

July 1, 2024 – Review

Rahima Gambo’s “Alternative Central Area Locations”

Michael Kurtz

When the Nigerian government confirmed its plan to construct a new capital in the seventies, it was intended to be a glorious symbol of a prosperous independent nation. Situated in the middle of the country, Abuja would unify the federation’s distinct ethnic groups, redistribute its growing population, and give concrete form to its booming oil revenue. But, mired by decades of political maneuvering and mismanagement, the city instead became a notorious example of the government’s neglect of its people in favor of ruling elites and foreign partners. The contract for the masterplan was won by a consortium of American firms and Japanese architect Kenzō Tange was hired to design the Central Business District. Over 800 villages were dispossessed of their ancestral lands to make way for the city, where insufficient housing stock later forced many into slums on the outskirts. The new capital had been dreamed up in corporate boardrooms around the world. In Rahima Gambo’s exhibition at Gasworks, a site-specific installation informed by archival research on Abuja’s development, it is as if things in one such boardroom have gone awry.

Two projectors play helicopter footage of Abuja, after its inauguration in 1991 but seemingly still under construction, on opposite …

June 28, 2024 – Review

Glasgow International

Daisy Hildyard

At the end of the first day of Glasgow International I sat on a straw bale at Tramway to watch Delaine Le Bas dancing on a white boxing ring that had been surfaced with eggshells. The performance, and the maximal neon and sequin installation of inked and embroidered sheets and bottled urine that environed it, made an emphatic point about life as a traveller now: “WE’RE NOT WALKING ON EGGSHELLS ANY MORE,” Le Bas shouted.

I was thinking about the hens. I wondered how long it had taken them to lay so many, many eggs, and whether each shell was from a different chicken, or some of them contributed multiple eggs as a durational project. Were the eggs free-range, or repurposed byproducts of the omelette industry? Around me the performers stamped and shouted; the audience watched, whispered, and sipped white wine. Meanwhile, elsewhere, the hens were roosting, having contributed time and body so that we could do… this.

I’m not taking any moral high ground here (I eat eggs for breakfast) but the warm, feathery, apparently collateral bodies intruded on my experience of the performance and I was unable to watch it on its own terms. I suspect this is …

June 26, 2024 – Review

Miranda July’s “New Society”

Wendy Vogel

“Do you love me, even though I’m sometimes irritating and a little bit selfish?” Miranda July asks in the brief audio recording The Crowd (2004). I wasn’t sure. I had spent nearly three hours in July’s solo exhibition at Fondazione Prada’s Osservatorio—the first major retrospective of her performance and visual art—and I was getting tired. Her voice echoed off the walls of the bathroom where the piece had been installed.

“That’s a good thing, because I love you too. I’m just not very good at it! But I’m trying to change,” she responds. A recorded audience cheers. “This song is for you and it’s a love song,” July concludes, her voice fading to the sounds of a band tuning up. As I washed and dried my hands, I warmed back up at the cheerful resolution. As though anticipating my grumpiness, the artist had assured me of her affection.

The Crowd is a succinct example of July’s signature performance move: vulnerability, bordering on neurosis, giving way to sentimental declarations that secure her power. She has a gift for connecting with an audience, cutting through the noise of a large group to create intimacy with individuals. Organized by Mia Locks, “New Society” …

June 24, 2024 – Review

Jordan Strafer’s “DECADENCE”

Stephanie Bailey

“The Kennedys. Palm Beach. A charge of rape. It all made for a real-life soap opera in May 1991 that resulted in an arrest, a trial, and non-stop cable TV coverage.” So reads a recent Miami Herald summary of William Kennedy Smith’s trial, when John F. Kennedy’s nephew was acquitted of raping a twenty-nine-year-old woman. New York-based artist Jordan Strafer fictionalizes that case in “DECADENCE,” an exhibition at the Renaissance Society showing two films back-to-back on a large standing screen, starting with LOOPHOLE (2023). Clocking in at twenty-four minutes (the standard runtime of a TV episode), and filmed in the style of a 1980s soap crossed with a true crime reconstruction, LOOPHOLE draws on sociolinguist Gregory Matoesian’s observations on the “matrix of language, law, and society” that he saw mobilized in Smith’s court proceedings “to create and recreate cultural hegemony”—which Matoesian found to be inextricable with patriarchy. Echoing Matoesian’s findings, Strafer zooms in on what Matoesian described as the poetic, aesthetic, and “persuasive rhythms of trial talk” designed to “organize and intensify the inconsistencies in the victim’s account and shape them into a cumulative web of reasonable doubt.”

LOOPHOLE plays with that doubt by embellishing proceedings with a Lynchian surreality …

June 21, 2024 – Feature

Zürich Art Weekend

Orit Gat

Heidi Bucher’s Skin Room (Rick’s Nursery, Lindgut Winterthur) (1987) is a mold made from latex and fish glue of a friend of the artist’s childhood room. On view at the Migros Museum as part of a collection show titled “Material Manipulations,” this “skin” hangs by clear strings from the ceiling: yellowish, haunting, still recognizably domestic. Next to Bucher’s sculpture, in Martín Soto Climént’s The Swan Swoons in the Still of the Swirl (Stills 1,2,3,4,5,6) (2010), metal Venetian blinds hang, spread like handheld fans, from ceiling to floor. These elegant sculptures, like Bucher’s work, figure the home as physical artifice, bricks and mortar, more material construction than abstract idea.

The effect is alienating and evocative at once, and the fragility of these homes suggests the impossibility of conceiving of the home as simple refuge. A second show at the Migros, Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape’s “(ka) pheko ye – the dream to come,” subverts this construction of home by bringing to the museum the very real conditions of Bopape’s native South Africa through clay display structures that echo the front yards in which people congregate, work, and socialize. Bopape makes a place for dreaming and “collective healing” through both objects—like the projector …

June 18, 2024 – Review

Tolia Astakhishvili’s “between father and mother”

Chris Murtha

Built from conventional architectural materials including drywall and cement, and later stained with coffee, dirt, and pigment to mimic the wear and tear of time, Tolia Astakhishvili’s installations hover between construction and destruction. SculptureCenter’s brick and cast-iron building, initially designed for repairing trolleys and later used to manufacture derricks, hoists, and cranes, proves a fitting host for the Georgian artist’s first exhibition in the United States. Having previously explored the mutability of domestic spaces, and how they accumulate the marks and alterations of their inhabitants, Astakhishvili here contends with a formerly industrial site, while still remaining focused on what spaces tell us about humans come and gone.

As she did with two recent exhibitions in Germany, Astakhishvili incorporates collaborative projects and works by peers into her installation—an extension of, rather than challenge to, authorship. A microcosm of the exhibiting institution, her fabricated environments become fleeting hosts for her own and others’ artworks. The first sculpture visitors encounter is Astakhishvili’s The endless House (all works 2024 unless otherwise stated), a freestanding cement and particleboard wall modeled on those found in the building’s basement. The structure’s narrow cavities harbor a sculpture and photograph by Katinka Bock and reverberate with the sound of …

June 17, 2024 – Review

“Patterns of (In)Security II”

Nina Chkareuli-Mdivani

Taking its name from Michel Houellebecq’s 2005 novel The Possibility of an Island, this artist-run space in Berlin’s Mitte neighborhood hosts the second iteration of a dual exhibition that hints at the possibility of establishing a space of refuge between divergent positions. Extending a collaboration that began in Tbilisi last year, Sabine Hornig and Tamuna Chabashvili seek to establish some common ground between idealism and pragmatism, collective and individual, order and freedom.