Aesthetic objects of art and design have unruly lives beyond their official business—they exist in homes, imaginations, shopping malls, state politics, and world histories in ways that are promiscuous and difficult to control. Over the last decade, Lucy McKenzie has depicted this pollination between forms in a captivating practice which unifies troubling, exciting, and mundane associative materials through the smoothing effects of style, most prominently trompe l’oeil painting.

Her exhibition at Galerie Buchholz’s New York space, “No Motive,” opens with Ethnic Composition (Moldova, Russian Ethnographic Museum) (2021), a kind of user guide to thinking through forms as composites of visual influence. Adopting the design of an informational display from the Russian Museum of Ethnography in St Petersburg, the artist painted a map of Moldova, divided into patches of cream, green, blue, and lilac, according to the styles of traditional dress in the country. On an “explainer panel” below, angled towards the viewer, we find, in place of any “key” to the data, six photographic prints: a mannequin in a museum display; a fashion illustration; a Mexican store mannequin dressed as “The Lady of Death”; a 1950s Russian department store mannequin; a young woman visiting a Moscow gallery; and, finally, an example of the promised “traditional dress” from the museum. Together, these coalesce into a miniature treatise on the figure of the mannequin, a subject that McKenzie has examined before with Beca Lipscombe (the two work together under the name Atelier E.B) for their touring show Passerby (2018–20), which showcased different histories of retail display, and offered a history of the mannequin as proxy body entangled simultaneously in aesthetics and capital. There she was, in the window all along.

“No Motive” continues to explore the figure of the mannequin through facture, collating histories into made things rather than arranging them as collected materials. Three polychrome mannequins, installed throughout the exhibition’s middle section, lean against the wall or sit cross-legged, dressed in 1920s couture. Their bodies are mass-produced by a leading mannequin company in its most “fashion-forward” shape, a notionally “progressive” body type which appears less unrealistically elongated than the current western industry standard, and which has more flesh on the arms. In place of their standard-issue heads, McKenzie has given them the sculpted head of Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya, a Soviet partisan who was killed at the age of 18 by German soldiers in 1941, and who is celebrated in a multitude of statues across the former USSR. In some of these official monuments Kosmodemyanskaya wears a plain uniform of a skirt and jacket, while in others she is an eroticized figure, bound with chains wearing torn robes, summoning the violence enacted on her body. When considered alongside the store mannequin, these statues of Kosmodemyanskaya—who has a sturdy face and a defiant expression—present another type of idealized public body, created under alternative political conditions.

At some level, these mannequins propose a body that collapses the aesthetics of socialist and capitalist ideologies onto one corpus. Yet McKenzie’s projects, including this one, are always threaded with suspicion towards such easily formed binaries. Instead we find an interlacing of commercial and state desires, muddled by aesthetic questions of frailty and strength. The delicate dresses that these figures wear, designed by Madeleine Vionnet and handmade by McKenzie during the lockdowns of 2020, introduce more layers of overlapping histories. The cutting patterns for the two Vionnet dresses, provided in the exhibition guide, are revealed to be arrangements of geometric squares that resemble Russian constructivist compositions, while a crepe dress, L’Orage [The Storm] (1922)—made in two different color schemes for the exhibition—is described in the pattern as having a “dull gold Russian braid,” a linguistic reminder of traffic in styles between regions. It remains a real source of delight to me that Vionnet’s profound innovation was to create patterns completely on the bias (hanging fabrics in a diagonal relative to their weave, so that gravity supplies weight and movement to a fabric that would otherwise hang more stiffly). The beauty of the bias, as an equation and concept, comes from its interaction with an element that is already present and freely available—gravity—which is incorporated into the design with a tilt shift. A possible analogy for McKenzie’s practice, in that her projects draw charge from things already there in the background, invisible until they are not.

What happens to these dresses on Kosmodemyanskaya, on this “edgy” body, which has also been painted in various schemes from Greek and Roman history in aubergine, terracotta, and polychrome white, and given eyebrows replaced with heraldic laurel leaves? Whilst Vionnet’s dresses are meant to hang in a way that makes the body more present, McKenzie has tuned up various attributes on the mannequins that are usually designed to recede into the background. These mannequins are not “invisible” white bodies, carrying with them a history of classical marble statues, but by negation they are reminders that every mannequin seen from H&M to Gucci carries specific codes of aesthetics and ideology in their form.

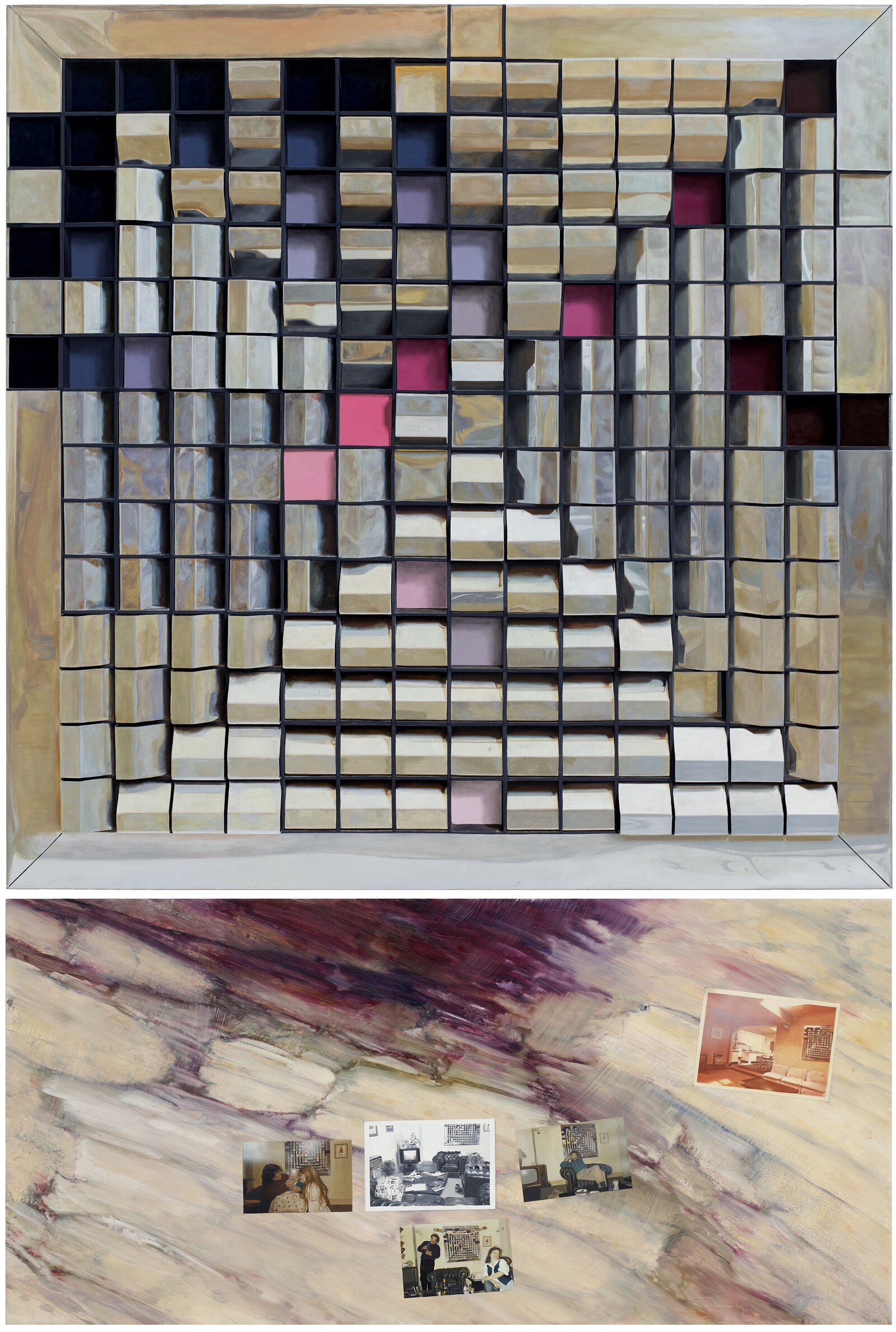

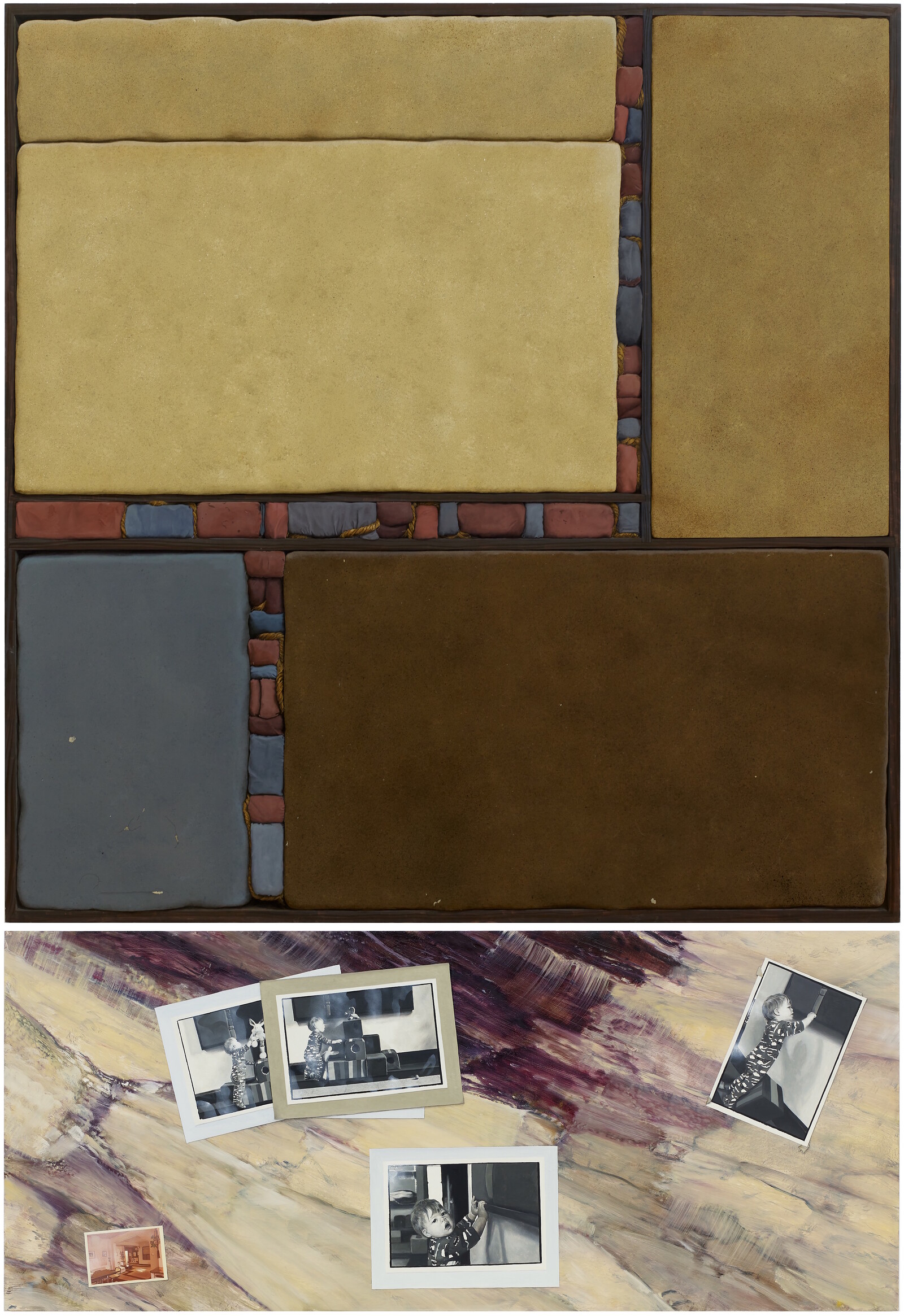

In three subsequent works, McKenzie reintroduces the form from Ethnic Composition to create three “explanatory” painting panels depicting a more personal background presence: three works of art that were displayed in the house where she grew up. These large, very sculptural pieces were by students from Glasgow School of Art, where McKenzie’s father taught art history from the 1970s to 2010, and each is almost muscular in its physicality: a wooden construction stuffed with rolled canvases, a grid of contorted metal squares, and an edifice of colorful sculpted elements. In the place of angled “explanatory information,” on the panels below McKenzie has painted family snapshots in which the works appear in the background, strung with Christmas cards, or being grasped by a toddler learning to walk. These scenes show us artworks in the wild, in rooms that do not have a coherent aesthetic, but which set the art among living bodies. It’s almost akin to seeing artworks be worn like garments, but we infer that these presences communicated something about artistic value to the young McKenzie.

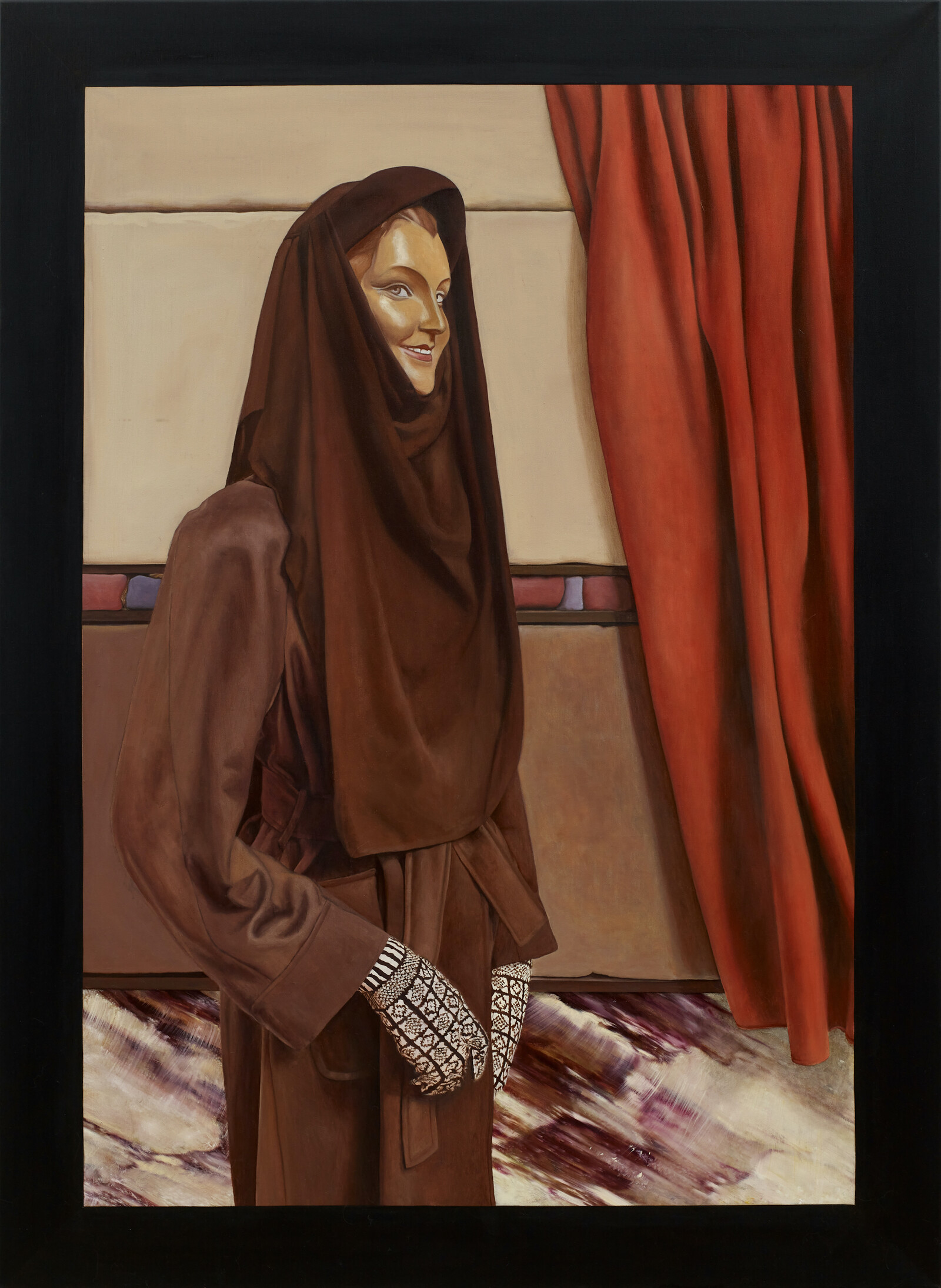

When the exhibition’s various reference points are synthesized in three paintings in the exhibition’s final room, Unfinished Mannequin Portrait I, II and III (all 2021), it is with some unease, as though the trick of creating that coherent aesthetic ideology has been revealed. These “paintings of portraits of mannequins” feature painted-on frames, and the artworks from McKenzie’s family home as backdrops. They are extravagantly beautiful in that chilly, highly finished way that McKenzie’s trompe l’oeil paintings so often are, but these mannequins, which have a wooden 1950s look to them, are uncanny and maniacal. One is pictured smiling and shyly putting a hand to her face, wearing the Vionnet L’Orage dress, but I notice a chip in her painted hand and hear the sawing laugh of a doll. McKenzie’s work has pulled a number of threads which finally cinch like curtains: everything appears stagey, corrupt. Elegance, but make it horror.