September 7–November 17, 2019

“When I was nine years old, the world was as old as me […] As I turned ten, all of a sudden it aged ten million billion years.”1 The Danish poet Inger Christensen (1935–2009) engaged with time and language as constructs. In her prose poem “Part of the Labyrinth,” she paraphrased Descartes: “I think, and therefore I’m part of the labyrinth.”2 The 10th Gothenburg International Biennial for Contemporary Art (GIBCA), which borrows its title from Christensen’s poem, centers on the inextricable future of history. Programing both for the current and the next edition of the biennial, curator Lisa Rosendahl has initiated a two-year contestation of the 400th anniversary of the city of Gothenburg, the concluding exhibition of which will be held in 2021. Linking demographic segregation with the discrimination of memory, this pair of consecutive, interrelated biennials examines how the city of Gothenburg can be read as an imprint of Sweden’s colonial unconscious.

In 1784, King Louis XVI of France ceded the South Caribbean island Saint Barthélemy to Swedish rule in exchange for a plot of land in Gothenburg’s port, and securing free trade between both countries. With its dissonant array of archival photographs and abstract prints mounted on candy-colored pink and blue wood, Eric Magassa’s outdoor mural Walking With Shadows (2019), installed in the city’s old harbor district, explores how local perspectives can be blind to the global impact of colonialism. In the displays at one of the biennial’s five venues, the Gothenburg Museum of Natural History, the label for a small brittle star reveals, without comment, its origin at Saint Barthélemy. Works by several artists are displayed amid the dense collection of animal bodies encased in wooden structures, which line the venue’s corridors.

“There is no life without a membrane,” states a voice in Hannah Black’s three-screen video installation Beginning, End, None (2017), installed on the museum’s upper floor. Its obscure narration sources the logistics of the livable, from the slave ship to the factory and, finally, living cells. The sentences scroll across the three channels: “It’s the end of the world / There has never been a world / It’s the beginning of the world.”

Christensen’s poem refers to the Italian philosopher, mathematician, and poet Giordano Bruno, who in 1600 was burned at the stake for insisting on a heliocentric model in which the universe was infinite and thus the earth was not the only planet in the cosmos. Before he was executed, Bruno wrote a series of letters in which he exhorted future readers to continue believing in the stars. GIBCA engages with this legacy by attempting to move beyond mechanistic time, and thus beyond the exhibition construct. While Black explores the packaging of life as measurable matter, Liv Bugge’s video The Other Wild (2018) looks to minerals and fossils from the former Geological Museum in Oslo, documenting the geologic and paleontological objects from its collection as they are moved or deaccessioned in preparation for relocation: the piling up of pebbles and sand erases whatever value was once projected upon them when they were extracted from the earth. Around the corner is Annika Eriksson’s slideshow and they were very loved (2017), a selection of analog stills from home videos of pets, in which the domestication of animals functions as a litmus test of human behavior. Beside the carefully shot pictures, the museum’s taxidermied animals attest to an opposite set of relations.

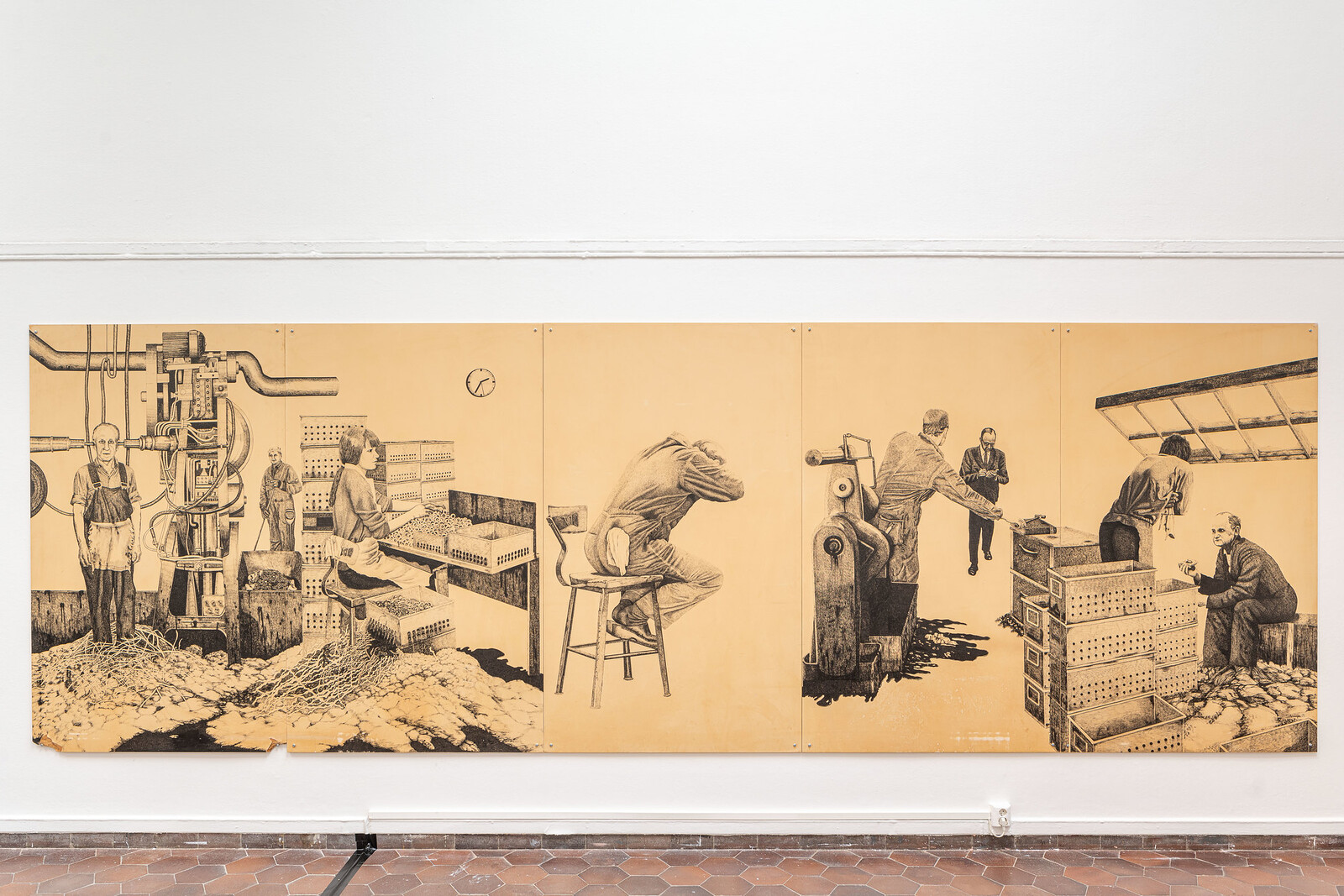

At the Göteborgs Konsthall, multimedia installations and videos negotiate language as surplus and warfare. Henrik Andersson’s photographic montage Ockulärbesiktning [visual introspection] (2017–19) features worn stone carvings from Underslös, north of Gothenburg, which are repeatedly re-interpreted by successive ideologies. Knud Stampe’s large Väggteckning [ink drawing] (1970–71) is similarly worn in appearance. It depicts workers, including the first female ones, in the then-dominant Gothenburg manufacturing company SKF. The drawing has been hanging in the SKF canteen since it was made and has yellowed over decades of exposure to cigarette smoke. Both works include laboring surfaces whose inscriptions—cultural heritage and workers’ rights—are weaponized subjects in contemporary debates.

At Röda Sten Konsthall, Michelle Dizon’s multimedia installation The Archive’s Fold (2018) enacts a paradox: how to look for oneself in an archive. Departing from the US occupation of the Philippines at the end of the nineteenth century and blending archival and family photographs, Dizon expands into the future as she gazes back in history, while questioning the mediation of the present. The collective Black Quantum Futurism invites visitors to do the same in their video meditation on non-linear memory, Time Travel Experiments (2017). At the core of the Konsthall display is Kent Lindfors’s collection of drawings and paintings that memorialize Bruno’s insistence of several worlds Vatten, Rost och Eld (Älven, Skrotmadonnan, Mannen i Båten. Och Giordano Bruno som bränns upp, februari 1600. Campo dei Fiori, Rom) [Water, Rust, and Fire (The River, Scrap Madonna, The Man in the Boat. And Giordano Bruno being Burned Up, February 1600. Campo dei Fiori, Rome)] (2016–19). Displayed in vitrines, Lindfors’s chaotic gestures also depict land and life lost due to fire and industrial extraction. Sprawling handwriting occasionally appears: “Everything is on fire,” reads a fragment, “Our consciousness is on fire.”3

Kajsa Dahlberg’s video interview with Danish dramaturg Ulla Ryum, Unbinding time (2019), could be read as a kind of manual to the biennial. “As a dramatist you aim for something, but when you take aim, what you’re aiming at looks back at you and in doing so, tells the story,” Ryum explains, while underscoring the role of sounding and embodied movement in storytelling. Her words emphasize the central role of bodily imaginaries at this year’s GIBCA, which posits bodies of land, economic bodies, captured and dissolving bodies in conflict throughout history.

Inger Christensen, Del av Labyrinten (Stockholm: Modernista, 2017), 11. Translated by the author.

Ibid, 43.

Translated by the author.

.jpg,1600)