Unknown Ideals collects a range of texts written by the artist and educator Zach Blas since 2008: essays, a screenplay, poems, and the hallucinatory monologue of a mannequin getting fucked by a suction gun. These writings, and a selection of installation shots and stills from the exhibited works which prompted them, are interspersed with critical responses by theorists and art historians such as Alexander R. Galloway and Pamela M. Lee, as well as an interview conducted with curator Övül Ö. Durmuşoğlu. The book is far from a collected works: writing is central to Blas’s practice, and he has published a long bibliography of academic writings on film, queer theory, and digital media. Yet beyond being a simple miscellany, it serves as an introduction to the distinctive imaginary world which has animated the artist’s work in film, digital media, installation, and sculpture.

The opening text, “Unknown Ideals,” offers a panorama of that world: California, the site of the contemporary “informatic means of production.” Blas’s California—perhaps like every California—is fantasy. A landscape, retro and futuristic at the same time, of Disneyland, meditation retreats, and Silicon Valley; inhabited by The Doors and Jack Dorsey, but dominated by Ayn Rand, whose 1943 novel The Fountainhead entranced Blas as an “arty queer kid stuck in the American Bible belt.” The text’s obsession with Rand, whose praise of “selfishness, her rejection of altruism, and her emphasis on a capitalist economy with no government interference” couldn’t be further from the political goals Blas expresses elsewhere in the volume, is the confession of an ambivalent desire—which is to say, a real one. It is also “uniform, not unique,” hinting at a wider ambivalence. It isn’t a coincidence that California was one of the origin sites for post-1960s gay liberation. Queer politics has been animated as much by collective struggle as by ideals of individual self-determination that overlap, queasily, with those offered up by Rand.

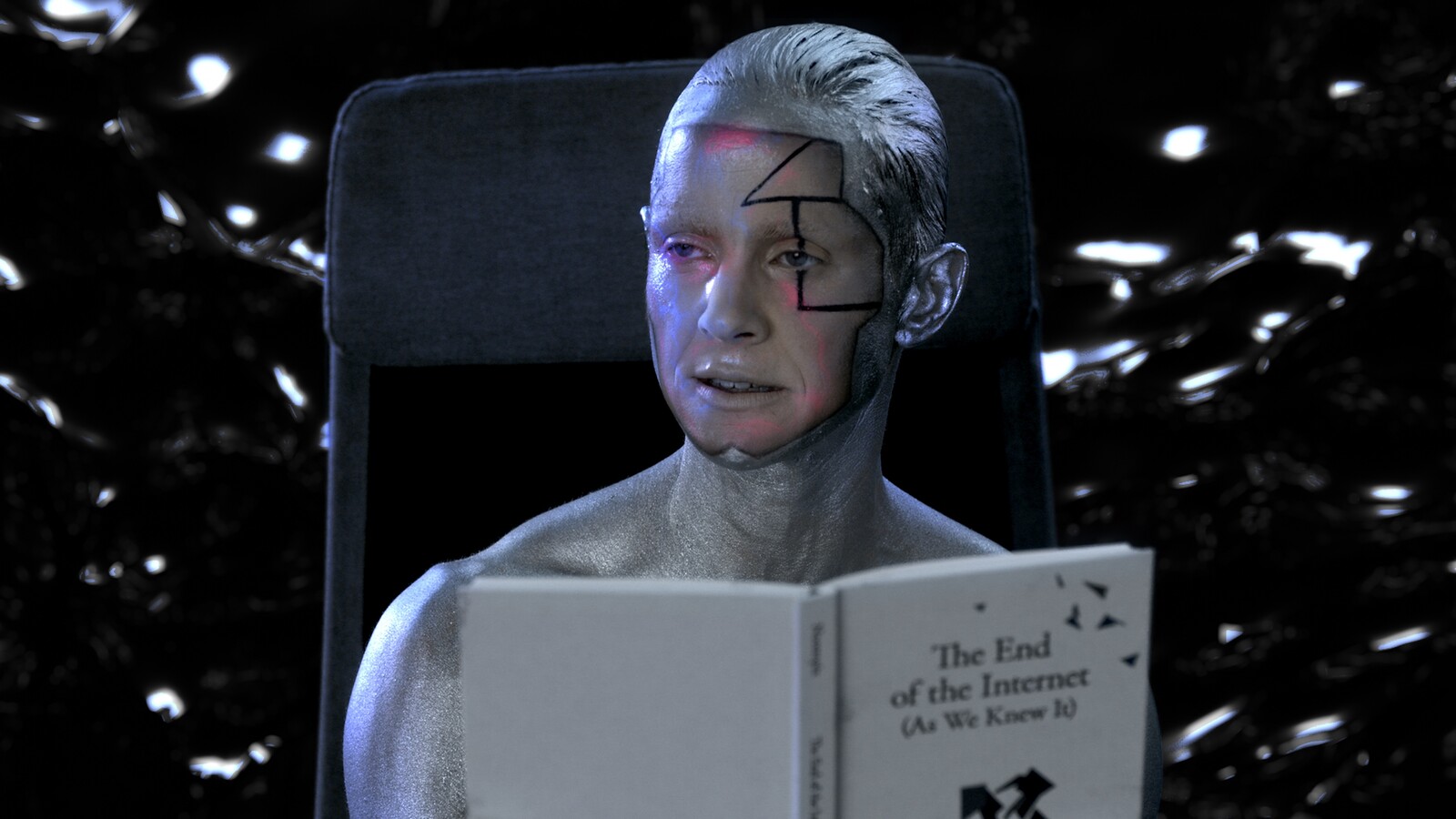

But the Randian ideal which runs throughout many of the texts that follow is that of a future, a telos motivating political struggles, technological change, and desire itself. “Jubilee 2033,” inspired by Derek Jarman’s 1978 Jubilee, presents the screenplay for a film, first shown in 2017, wherein Rand, Alan Greenspan, and his wife, Joan Mitchell, are transported to the future by an artificial intelligence programme called Azuma. In 2033 the internet has collapsed and the earth is toxic, yet still these “California prophets” predict a future where “Enlightenment dreams itself anew in software.” “Elf’s Predictions” also expresses the unstinting ability of the technological capitalism that Rand embodies to envisage a future. In this text, predictions are all an AI bot can offer. “Ask me,” it commands, “what the only path to tomorrow is.” It’s hard not to think of Fredric Jameson’s quip, made ubiquitous by Mark Fisher, that the problem of anti-capitalist politics is “that it is easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism.”1 Capitalism has monopolised the imagination of ends, of telos. If every end is the object of a desire, then our desires become that which needs to be changed by that software, dreaming itself anew.

Not that, as suggested by the travails that unfold in “Generic Mannequin Gets Fucked,” Blas holds any simplistic utopian vision of digital technology, desire, or even queerness as a site of political identification. What unites the work collected here is an insistence that the desires unleased by digital technology—individualistic, narcissistic, and controlling as they may seem—cannot be avoided for any politics today, queer or otherwise. Those visions might be—might have to be—as kitsch as the visions of liberation offered by the prophets of Silicon Valley. “Ego Death Party,” a concluding poem, observes that “Sadness has ravaged the friends of Utopia […] Let me take you to a place / Of higher elevation / the sun in curved green clouds / Cactus, palms, swaying, and intensely boundless jungles of geometry.” But maybe a bit less seriousness about desire is exactly what is needed to unleash a future that will compete with the metaverse. Maybe a bit more naivety is needed to realise Blas’s own dream for the future: “After the internet, there will be dildos.”

Zach Blas’s Unknown Ideals was published by Sternberg Press and the Edith-Russ-Haus for Media Art, Oldenburg in January 2022.

Fredric Jameson, “Future City,” New Left Review 21 (May-June 2003), 76.