April 21–November 24, 2024

The earliest work in Rossella Biscotti’s first institutional survey predates her training at the Naples Academy of Fine Arts by a decade. In 1991, when she was 12, the Vlora, a hijacked cargo ship carrying some twenty thousand Albanian refugees, unexpectedly docked in the Italian port city of Bari, near where Biscotti grew up. Many of the economic refugees were housed in a disused stadium. Skirmishes with Italian authorities ensued, resulting both in the refugees being repatriated and stricter border policies being implemented. A year later, Biscotti took a black-and-white photograph of the Adriatic Sea from Bari; using pen, she later superimposed onto this photo the outline of a hill, which she labeled “Albania,” also adding a fence, its central feature identified in Italian with the word cancello, or gate.

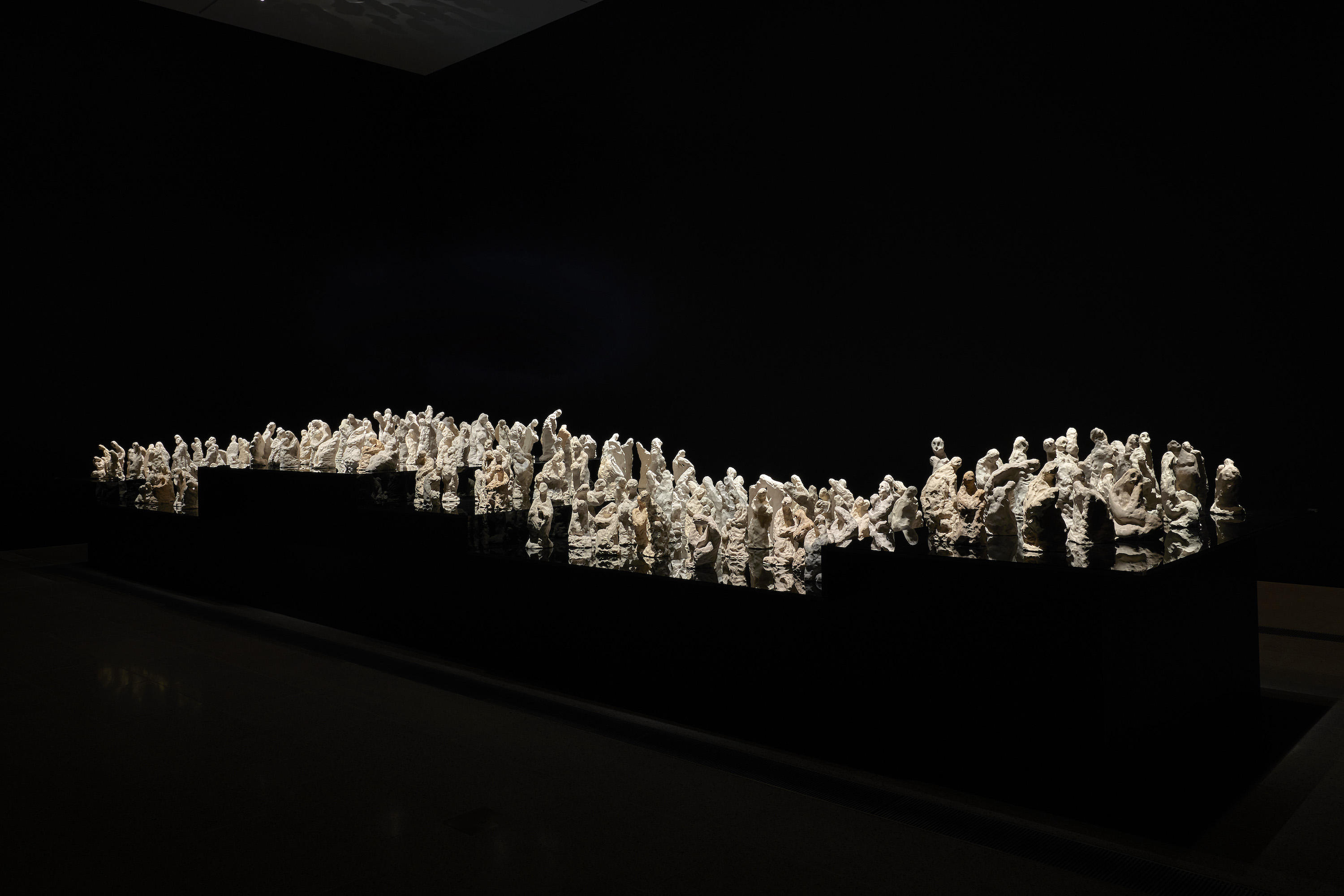

Displayed in the first of six rooms devoted to Biscotti’s thematically fluid and research-intensive work, this untitled photo highlights the importance of the sea in the artist’s work. Far from being a hackneyed subject, the sea emerges—episodically rather than serially—as a space that has enabled Biscotti to develop and refine her central artistic gesture: the recovery and visualization of “untold stories and unrepresented people”.1 Take Clara (2016), a sculptural installation composed of a mound of dried tobacco leaves flanked by three wooden palettes loaded with equal-sized masses of hand-made Dutch bricks, each embossed with the image of a rhino, and accompanied on a nearby wall with a numeric value (“100,000”) in vinyl lettering. Previously shown in Amsterdam and Venice, and here installed at the midpoint of the exhibition, this peculiar assembly materializes elements of a colonial-era seafaring narrative.

In 1740, a Dutch sea captain with the Dutch East India Company (VOC) acquired a domesticated, female Indian rhinoceros, the titular Clara, in Bengal, which he brought back to The Netherlands and profitably toured across Europe for seventeen years. Biscotti’s installation draws on her research in VOC archives, which revealed the use of brick loads to simulate the weight of traded goods for ship transport and tobacco to pacify Clara during her voyage, as well as the royal sum in gold coins offered by King Louis XV for the animal’s purchase; the sea captain refused to sell. The installation is accompanied by one of Pietro Longhi’s many depictions of Clara on display at the Venice Carnival in 1751. Flanked by her keeper, who bears a whip, Longhi’s painting includes a corpulent, wigged dandy with monocle engrossed by the strange mammalian sight from across the sea.

Shown near the exhibition’s acoustic conclusion, The Journey (2021) reprises Biscotti’s early interest in mute seascapes. The work is made up of three black-and-white photographs depicting the Mediterranean Sea. In 2021, a decade after winning the Michelangelo Prize at the 14th International Sculpture Biennale in Carrara, Biscotti dumped her award, a twenty-tonne block of marble, into this sea at an undisclosed location after directing the ship to follow a symbolic route between Italy, Malta, Tunisia, and Libya. The three photos record the water at the moment the marble block was released. On an opposite wall, a hand-drawn formula calculates the speed of the block’s liquid descent. In the final room, the museum’s Attic, Biscotti’s eight-channel sound installation, The Journey (2022–23), sonically relives moments in the block’s journey from terrestrial quarry to watery grave.

The sea is a primordial geographical space, but it is also, as Allan Sekula insisted, “absolutely a space of contemporaneity,” a lived space of transnational trade, military economies, and—as Biscotti recognized as a teen—migratory flows with uncertain outcomes.2 Admittedly, Biscotti’s affinity for the sea as subject, and her flexible attitude to its formal expression in her recuperative practice, was not the first thing I took out when viewing her occasionally recondite exhibition, which curator Marianna Vecellio has thoughtfully and elegantly pieced together from about two-dozen known and previously unseen works.

Notwithstanding a tendency to express her research projects in diverse media, from deadpan photography and cinéma vérité film to performance, Biscotti consistently deploys sculpture. The legacy of minimalism is palpable in her output. Title One: The Tasks of Community, two separate works made in 2011 and 2012 that share the same title, each comprises rectangular lead blocks made from a decommissioned Lithuanian nuclear plant. The two works, which are distinguished by the size of the lead blocks, are displayed Carl Andre-style in distinct floor arrangements. This interest in distillation and elemental forms recurs in Crude Oil (2016), another work comprising three nearly similar parts, here three rusting metal bowls each displaying a black glass made from waste materials at a Murano glass laboratory.

The solidified ooze, which includes bubbles, references oceanic oil spills. It is profitably shown in the same room as Circulations (2024), a new commission informed by Biscotti’s research into the sublimated corporate history of Italian-Argentinian pipe manufacturer Tenaris Dalmine. Typical of Biscotti’s toned-down industrial hues, Circulations features six carbon steel pipes, the largest of which bears marks and incisions quoting ventilation systems in the mud dwelling at At-Turaif in Saudi Arabia, while the remaining five, smaller pipes are bent out of shape like wet spaghetti. The pipes are apt ciphers in an exhibition that loosely connects aspects of Biscotti’s recursive practice, suggesting linkages and nodes across time and material.

Jelena Martinović, “Creating Archives for Untold Stories and Unrepresented People: In Conversation with Rossella Biscotti,” Widewalls (June 17, 2024): https://www.widewalls.ch/magazine/rossella-biscotti-interview.

Jack Tchen, “Interview with Allan Sekula,” International Labor and Working-Class History vol. 66 (October 2004), 155–172.