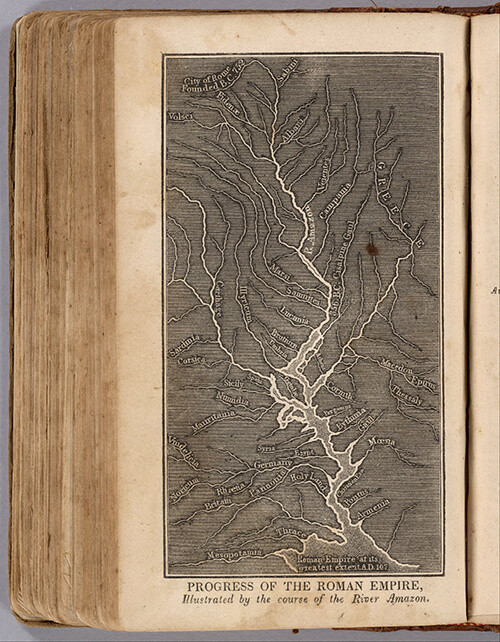

Riddled with countless tributaries, a map of the Amazon River and its drainage basin seemingly presents an image far too complex to be used as the basis of a mnemonic device; however, Emma Hart Willard (1787–1870), a radical American pedagogue and women’s rights advocate, turned explicitly to its topography in order to graph the history of the Roman Empire. Whether or not such didactic approaches assist in retaining cultural memory, Willard’s convoluted representation of a “canonical” history might also belie a subversive want and need to drown out reductive narratives. This year’s Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art—in a vein not dissimilar to this parallel reading of Willard’s work which is featured in “Double Lives,” a kind of exhibition-within-the-exhibition curated by Artistic Team member Natasha Ginwala—ostensibly claims to redress a spate of historical revisionism found in Berlin today; however, it does so in a rather oblique manner.

Aside from the artworks on view, the implications of curator Juan A. Gaitán’s ambitions for the 8th Berlin Biennale can be parsed through his selection of three different exhibition sites: KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Museen Dahlem – Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, and Haus am Waldsee. Key amongst them, however, is the Museen Dahlem, a state museum complex of three different institutions (the Ethnologisches Museum, the Museum für Asiatische Kunst, and the Museum Europäischer Kulturen) in the far west of the city. While issues of cultural appropriation abound within any anthropological collection, a tangential concern can here be found by looking not at that which is on display, but that which is missing.

Although contents of the 8th Berlin Biennale and the permanent collections are more or less segregated in Gaitán’s staging, a visitor still must walk through most of the museum complex. As such, one encounters sets of empty vitrines and displays interspersed amongst the objects on view (some of these absences are merely incidental, others by design). Speculatively speaking, these vanished artifacts could be said to symbolically represent a controversial aspect of the city’s cultural politics, specifically the relocation of the non-European and ethnographic collections to the Humboldt-Forum, a new facility in Berlin’s central Mitte district, which is currently under construction. Likewise, the top-down refusal to develop the Humboldt-Forum into an institution with a more current and self-reflexive program has led to claims that the project embodies a possible whitewashing of the past, and a growing homogenization of the city’s cultural future. When it comes to this year’s Berlin Biennale, these processes seem to be condensed into an obsession with museology to such an extent that the politics of display and site are marshalled here as a kind of cypher.

In a very diagrammatic way, Gaitán’s showcase, which creates literal correspondences between the Biennale’s different exhibition venues, advances this agenda. One work in particular is Judy Radul’s Look. Look Away. Look Back (2014). Housed in KW Institute for Contemporary Art—the institutional home of the Berlin Biennale—the installation relies on several surveillance-like cameras that intercut live video images of viewers peering into display cases at KW with recorded footage from the Ethnologisches Museum in Dahlem. Two hanging monitors at the end of the corridor capture these parallel views, so as to make a library of “gazes” between spaces virtually indistinguishable from another. While it’s hard to discern what purpose these abstracted images—which primarily present cropped design objects—actually serve, its aesthetic obsession with framing dominates any discussion of the above-mentioned politics. On a more conceptual level, softer links are made between KW and Dahlem-as-ethnographic center in Leonor Antunes’s elegant installation a secluded and pleasant land. in this land I wish to dwell (2014), which invokes Kuikuro craft techniques to create trans-historical and transversal links between various means of fabrication and their related traditions. The same is true for Bianca Baldi’s coy Zero Latitude (2014), a video that unpacks a Louis Vuitton “Explorator” trunk, the portable camp-in-a-box first built to the specifications of Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza (1852–1905), the Italio-French colonial explorer after whom Republic of the Congo’s capital city of Brazzaville is named.

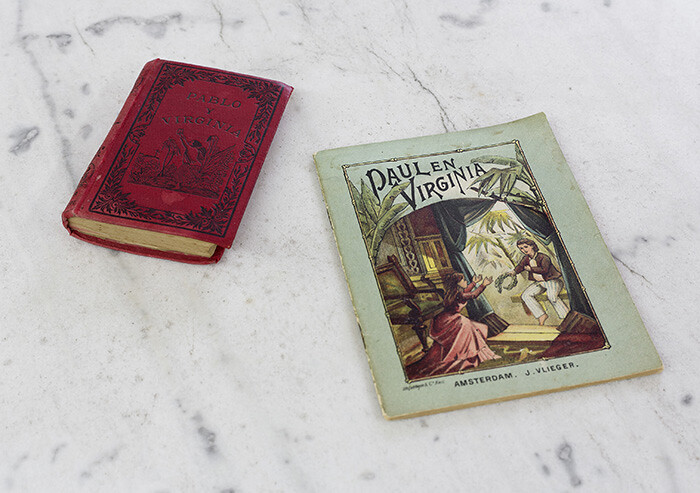

Similar polarizing and networked moves underpin the works at Haus am Waldsee in Zehlendorf. And like Museen Dahlem, Haus am Waldsee also has a particular history that this year’s Berlin Biennale wishes to broach, particularly that this exhibition space—since 1946—is housed within a posh villa and romantic garden built in the 1920s for a wealthy Jewish industrialist who later sold the house under duress as the Nazis came to power. As a kind of counter to the negative revisionism found today in the Humboldt-Forum, the space was initially converted into a gallery that first featured works by Käthe Kollwitz and other so-called “degenerate artists” censored by National Socialism. For the Biennale, Carla Zaccagnini (in collaboration with Theodor Köhler, Ayara Hernández Holz & Felix Marchand) wonderfully adds to the these intertwined histories of idealization and marginalization by presenting Le Quintuor des Negres, encore (2014), a sort of chamber ballet and installation based on Jacques-Henri Bernardin de Saint-Pierre’s 1788 novel Paul et Virginie—which invoked the idea of the noble savage as a way to ridicule the then divided social classes in prerevolutionary France—with a score based on a musical fragment. On the floor above, Matts Leiderstam presents The Connoisseur’s Eye (2014), a group of reproductions of oil paintings that Leiderstam culled from the collection of Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie (among other sources) with the catch that both the name of the artist and the sitter are now lost to history. Here, the intrinsic value of an artwork is itself put to task as the anonymity of both the painter and the subject has consigned the artwork to deep storage.

While the inter-textual dynamics in Dahlem come closest to answering the question of why this exhibition has been launched here and now, much of the artwork shown there seems itself to be decontextualized. For example, issues concerning censorship, colonialism, and corruption under the British Raj—found in the incredible editorial cartoons that the Kolkata-born Gaganendranath Tagore (1867–1938) drew in the early twentieth century to satirize the processes of each of these injustices—are set next to a video installation like Vanishing Point (2013), Jimmy Robert’s mesmerizing critique of hetero-normativity in Brazil; shot originally on Super-8 film, a dancer in drag thrashes against an empty and austere tower by Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer (1907–2012), with the reading of a 1979 protest poem by Ana Cristina César (1952–1983) functioning as a kind of soundtrack to the ensemble.

While intersectional struggle can be flirted with by joining César et al.’s anti-dictatorial words with Tagore’s anti-censorship polemics, the exhibition leaves such specific commentary just outside the frame. However, some social critiques are made more legible in the works themselves, such as in Carolina Caycedo’s YUMA, or the land of friends (2014), an oversized satellite photomural on glass in the Museen Dahlem depicting an aerial view of the environmental devastation wreaked by the current construction of the El Quimbo dam in Columbia, which includes a plaque listing statistics about the dam and its impact on the area. Along these lines, it should be noted that the show is almost devoid of didactic material, even though many works are research-based, and as such, the histories in which the above conflicts were situated lose their complexity. As far as the future of Dahlem goes, it is worth considering that the Biennale populates soon-to-be-evacuated spaces, and thus contends with the impulse to move the collections to a more accessible location. However, such gestures aside, no critical position on the matter is ever directly voiced in the exhibition.

If it can be said that the last Berlin Biennale pushed the art out in favor of some form of advocacy, this exhibition seems to reverse this logic insofar as incredibly powerful, and often highly political work is present here, but it appears to be more about dramaturgy than declarations. Giving this year’s Biennale the benefit of doubt, the works included are exceedingly rich, and to this end, the show has to be commended. However, a little more information, which might have teased out the nuances of these strong works and contexts further, would be the best counter to the potential uniformity of the city’s forthcoming Humboldt-Forum.