December 9, 2011–February 26, 2012

Commenting on new work by a “great” artist is always difficult. The task is fraught with paradoxes. After all, the moment you’re faced with recent work from an artist who has long ago been elevated to the canon of contemporary art history, what is there left to say? The work is a bit better than before? It’s a bit worse? It’s completely changed but the new stuff is still OK too? In essence, the more provisional, fleeting act of criticism grinds up against the massive gears of institutional validation—all the scholarship, the essays, the catalogues, the market values… the sheer sense of reputation that is at stake. And, of course, great artists nowadays no longer do us the courtesy of dying young, but carry on, being relentlessly great, making new work, for decade after decade after decade. Like Mick Jagger.

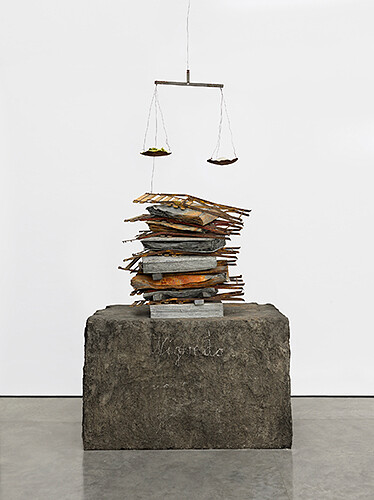

Now, if any artist’s work bears down on you in these terms, it’s that of Anselm Kiefer. Here in the huge, museum-scale galleries of White Cube’s newest branch, Kiefer presents six typically enormous paintings, and a host of sculptures, mostly from the last two years, but with a few dating back to the end of the 1980s. Winding through them is Kiefer’s perennial interest in the esoteric world of alchemy (the show’s title refers to the 1926 alchemical treatise by the obscure individual called Fulcanelli) and the artist’s enduring iconography of history-as-myth and history-as-disaster, wrought from heavy, uncompromising materials that he imbues with sub-Beuysian symbolic weight—lead, steel, wood, oil paint, charcoal, and plaster. Dominating the biggest canvases are depictions of Berlin’s Tempelhof airport, designed by Albert Speer as part of Hitler’s grand vision for the German capital. There are reoccurring motifs: the blackened, bedraggled, upended or fallen sunflower stalks, stripped of their petals and cast in resin, such as those that hang down over the vast, seventeen-meter-long scene of Tempelhof’s interior, Dat rosa mel apibus (The Rose Gives the Bees Honey, 2010–11); books made from lead or steel, splayed open or stacked in piles; effigies of fallen airplanes; blackened angels’ or birds’ wings modeled from twisted metal; measuring scales or scales of justice.

It’s impressive, big, gigantic, and that, if little else, seems to be the guiding principle. Big themes, big ideas, big obscurely literary and philosophical references, a sense of History, big H, political history, that is, as something enormous, catastrophic, and incomprehensible. Europe. Germany. Nazism. The Holocaust. All forged in massive forms and in tenebrous hues, wrought with sweat and sinew, scarred by the tragedy of time….

It is, nevertheless, a little bit…well… ridiculous. Partly because in order to buy into the apparent grandeur of Kiefer’s vision, one needs to acquiesce to these relatively conventional, liberal attitudes regarding the scope of politics and of human history. Kiefer’s shtick invariably plays to a mainstream, liberal notion of the experience of recent history as something terrible, traumatic, and so unknowable that it verges on the sublime, and it is only from that perspective that the solemn, sometimes melancholic, sometimes apocalyptic tone of Kiefer’s work resonates and draws strength. It is only from that perspective that Kiefer’s gesturing towards occultism, pre-modern mystical folklores, and Judeo-Christian motifs of redemption and renewal can make sense—chiming with a contemporary liberal imagination now profoundly disillusioned with the failed promises of modernity and the idea of progress, and more comfortable with cultural affirmations of pathos, fatalism, and catastrophe.

Without the consensus-culture that surrounds Kiefer’s oeuvre, however, these works become diminished; flamboyant concatenations of symbols that gesture towards these ideas as if they were great profundities, rather than the cultural clichés that they really are, and the now-routine working-over of these themes in Kiefer’s work only emphasizes their conventional status. Kiefer has recently stated that “only by going into the past can you go into the future”—but in his repetitive performance of the traumatic-cathartic return of history, he seems eternally stuck in a present from which he can do nothing but look backwards.