Innas Tsuroiya

R.H. Lossin

Ben Eastham

Stephanie Bailey

Michael Kurtz

Critical writing from the expanded field of contemporary art.

Editor-in-chief

Ben Eastham

Editors

Patrick Langley

Francesca Wade

Assistant Editor

Novuyo Moyo

Contact

criticism@e-flux.com

See Credits

Close Credits

Categories

Subjects

Authors

Artists

Venues

Locations

Calendar

Filter

Done

February 19, 2025 – Review

Ahmad Sadali’s “Bound to the Earth, Aspiring to the Sky”

Innas Tsuroiya

Alongside pioneering abstract art in Indonesia, Ahmad Sadali was an influential scholar and religious thinker, a public muralist who strived to ignite the spirit of liberation during the 1945 war, a national representative at UNESCO, an observer at the Bandung Conference of 1955, and an orator at Jummah prayers who gave a celebrated speech at Istiqlal Mosque, Jakarta, in 1975. Yet even before his death in 1987, his legacy—like that of the Bandung School with which he was affiliated—was dogged by controversy over its relationship to western art histories.

“Bound to the Earth, Aspiring to the Sky,” held in a gallery owned by one of his former students, is timed to celebrate the centenary of Sadali’s birth and grouped according to the artist’s formal tendencies—from simple geometries to golden ornaments—instead of a rigid chronology. In the larger of the gallery’s two rooms are forty-five canvases that evidence the artist’s distinctive styles, from the still lifes and Cubist styling of his early career, to later works incorporating Quran verses and the Names of God into calligraphic abstractions. The show draws attention to a controversy begun in 1954, when art critic Trisno Sumardjo argued that a group show of Bandung-trained artists “served …

February 14, 2025 – Feature

Godlike and free?

R.H. Lossin

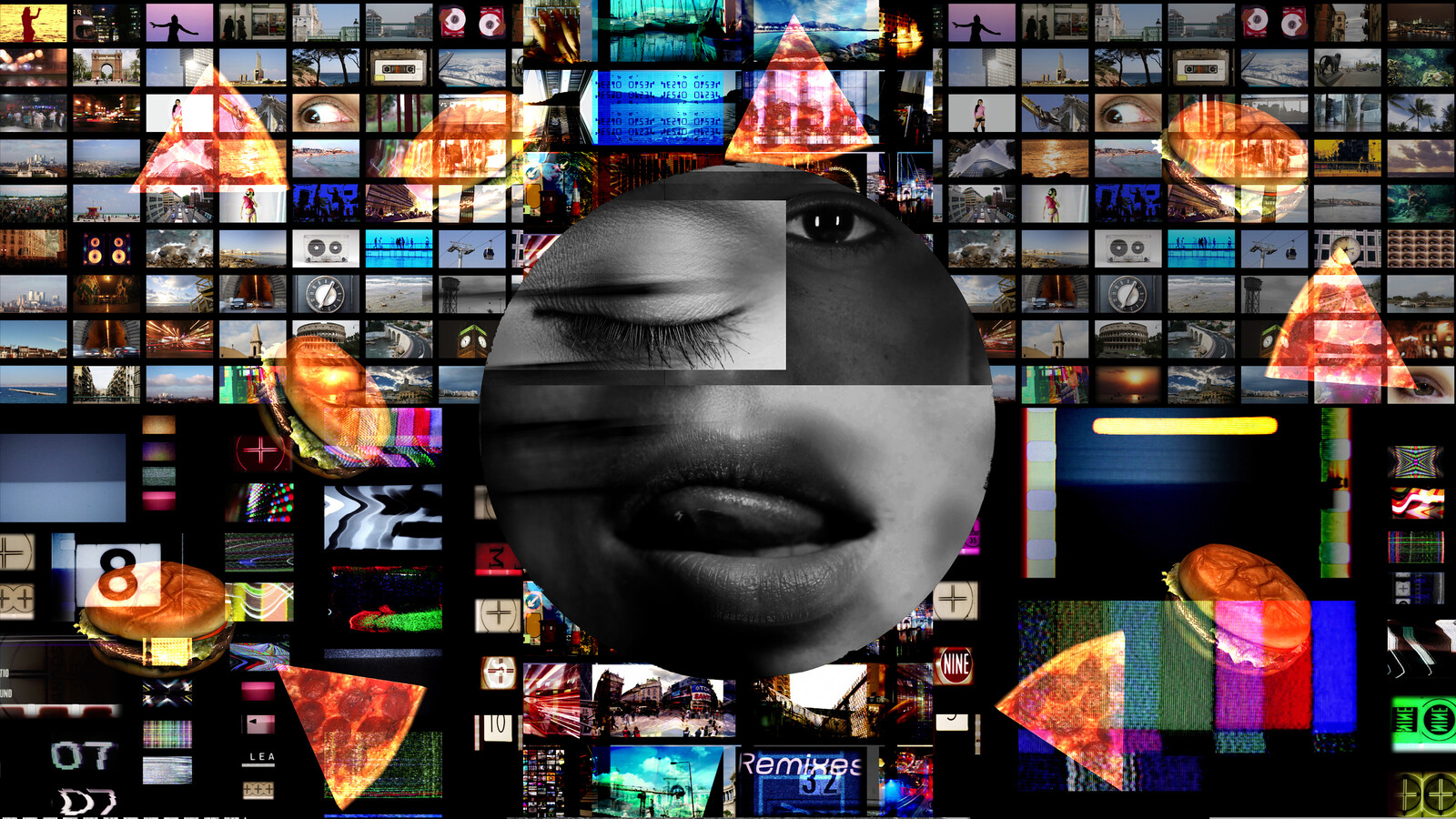

This is the second part of an essay by R.H. Lossin on the relationship between art, artificial intelligence, and emerging forms of hegemony. The first instalment was published on January 17 and can be accessed here.

Rashaad Newsome debuted “social humanoid artificial intelligence” Being at LACMA in 2019. The “robotic griot” (pronouns they/them) initially functioned as a guide to gallery visitors, and was designed “with agency in mind.” This meant that Being, unlike most service employees, wouldn’t respond predictably to user demands, but instead could “go rogue.” Other iterations of Being, trained on different data, have offered culturally sensitive app-based therapy to address experiences of racism, and led decolonial workshops. The major political claim made by Being is that it is an AI trained on a “counterhegemonic” dataset made up of “alternate histories and archives such as abolitionist, queer, and feminist texts” by Paulo Freire, Cornel West, bell hooks, and others. The dataset is organized using “non-Western indexing methods” (although it is unclear exactly what this means in relation to texts written in English and Portuguese).

Being is visually represented in a humanoid animation whose movements were partly derived from “the gestures and movements of vogue practitioners proficient in styles ranging …

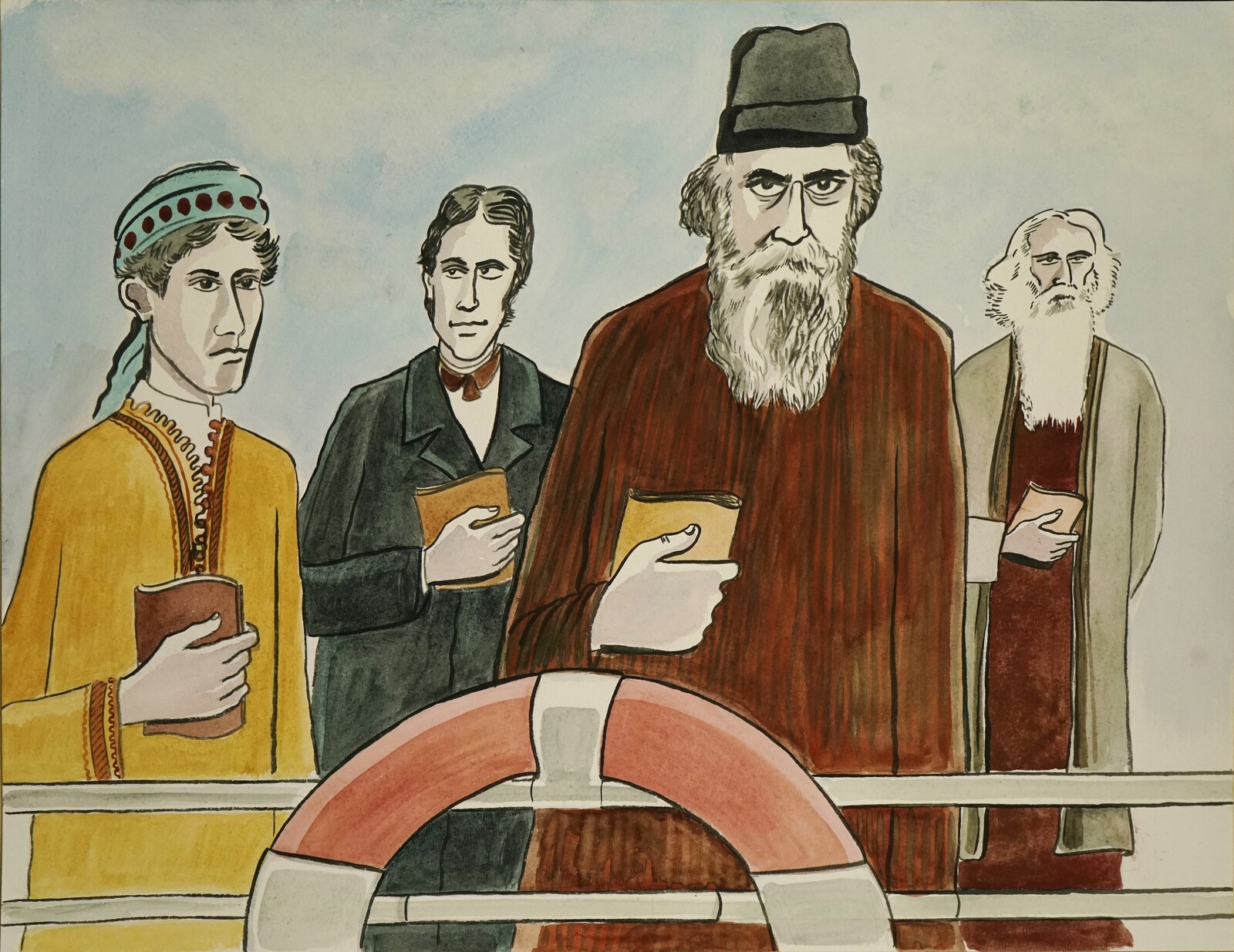

February 13, 2025 – Review

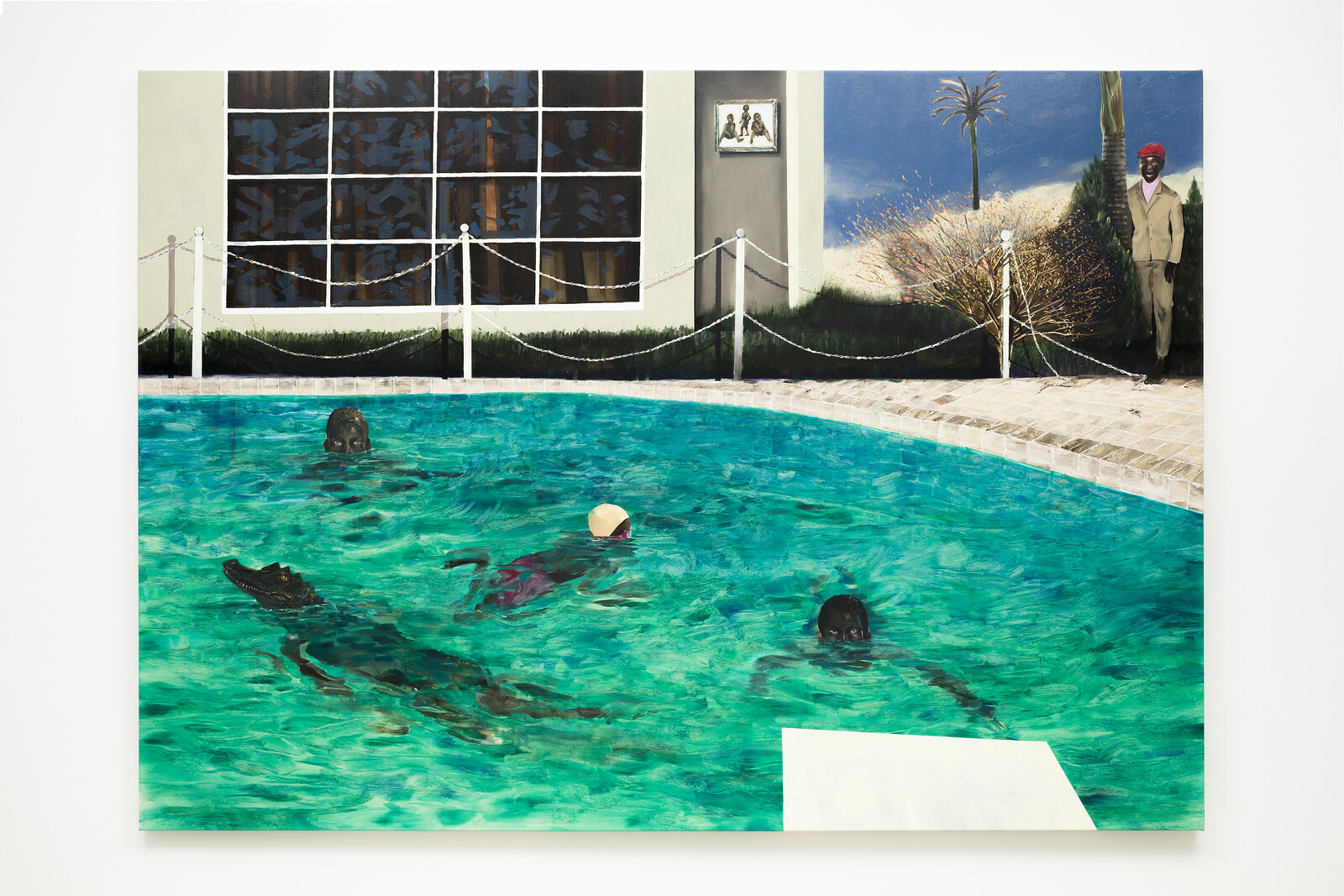

Sharjah Biennial 16, “to carry”

Ben Eastham

Nicholas Thomas has characterized Paul Gauguin’s Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? (1897) as a “success as a painting, but a failure as a work of art.” Which is to say that while it dazzles through its arrangement of color and form, it travesties the Tahitian culture that it purports to depict and offers no meaningful response to the grand questions of its title. The phrase recurred to me throughout this sixteenth edition of the Sharjah Biennial—curated by Natasha Ginwala, Amal Khalaf, Zeynep Öz, Alia Swastika, and Megan Tamati-Quennell—with its emphasis on work that is, by contrast, firmly grounded in its cultural contexts and unambiguous in its ethical commitments. But it is less clear that all of them fulfil the first part of Thomas’s equation, and triumph on their own terms as sculptures, videos, installations, or any of the other aesthetic strategies through which it is possible “to carry”—as the exhibition’s title puts it—ideas, principles, and feelings across the borders separating people, communities, and cultures.

Mangku Muriati’s paintings succeed on both counts. Drawing on the traditions of Balinese puppet theater, the new commissions exhibited on Calligraphy Square, in Sharjah’s reconstructed historic …

February 11, 2025 – Review

“Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet”

Brian Dillon

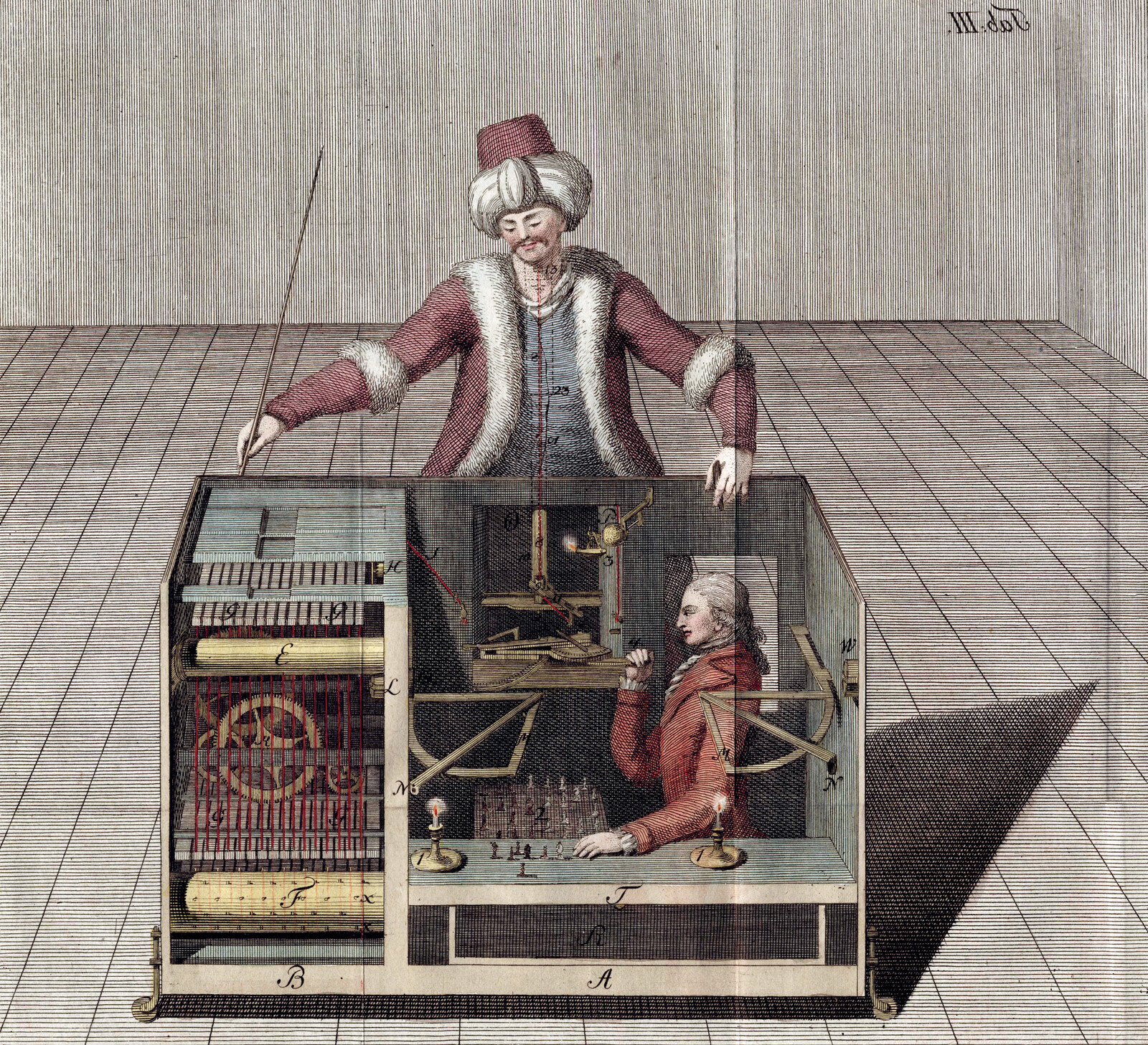

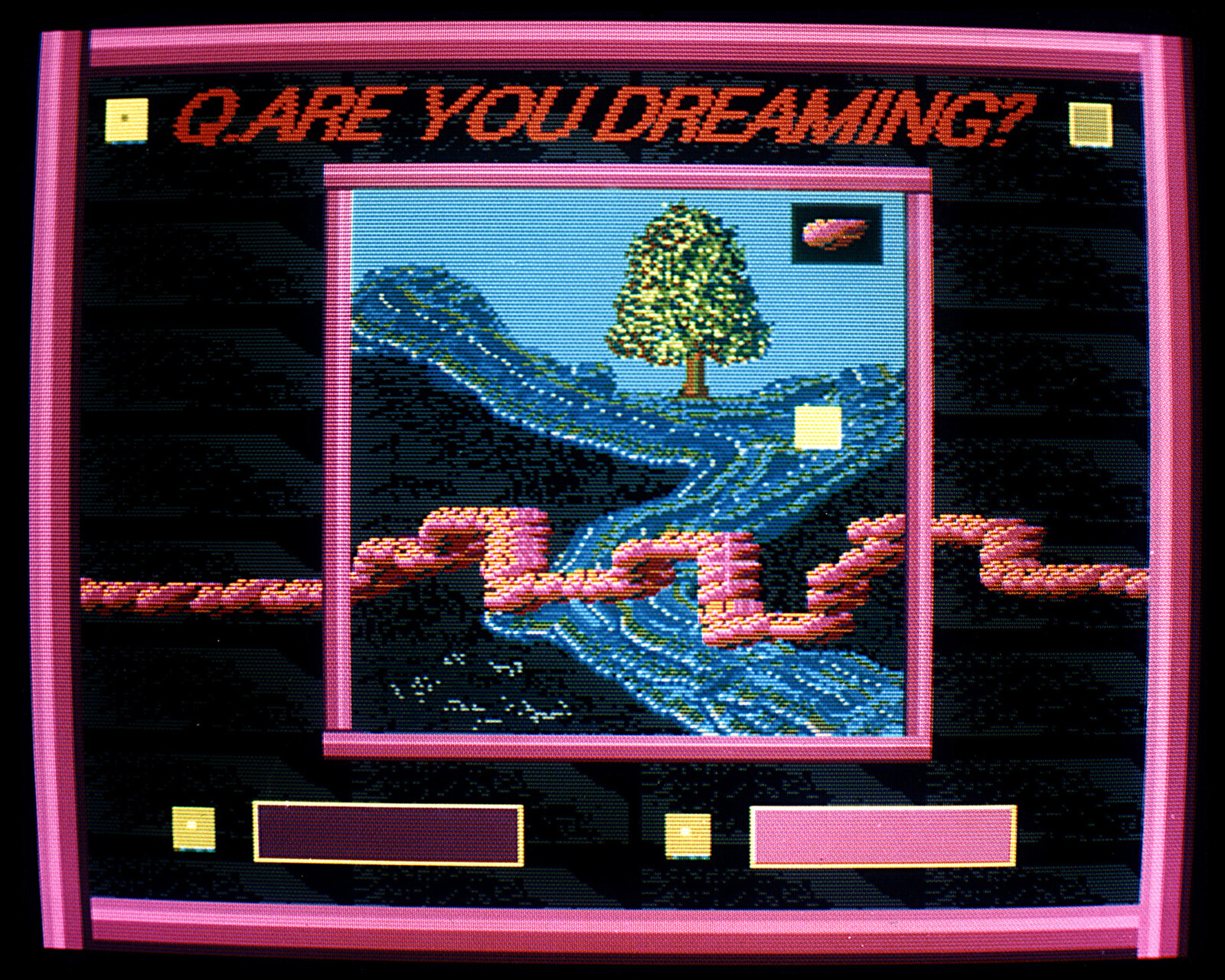

Imagine a historical juncture when machines promised to annex much tedious labor, manual or mental; to gather and strew the vast array of human knowledge at speeds and scale not dreamed of in our present technology; to pilot our imaginations towards new form and content in the arts, even new emotions and sensations. And at the same time threaten to steal our jobs and loot our private lives, tell us lies and fill our world with futuristic kitsch or inhuman austerity. Imagine if certain grim technicians enriched and refashioned themselves as prophets of this transmutation. And so on—the time of course is our own and not. It might be the post-WWII rise of techno-rationalism and information, the thrill of personal computing in the early 1980s, internet boosterism a decade later, the present perplex of competing perspectives on AI. Or the mid-nineteenth century, with its steam trains, telegraphs, and offset printing presses. In a crude history of modernity, the bourgeoisie is always rising, and technology the ambivalent object of faith and foreboding.

In other words, “Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet”—a survey that runs from the 1950s to the early 1990s, and commendably foregrounds artists and movements from Latin …

February 10, 2025 – Review

Climate Propagandas Congregation

Stephanie Bailey

The two-day Climate Propagandas Congregation was marked by urgency. Organized by Basis Voor Actuele Kunst (BAK) and artist Jonas Staal, it was the final event before BAK’s defunding by the Utrecht municipality and Dutch Council for Culture, reflecting a trend of arts institutions buckling under economic and political pressures, all while western governments openly flout international law and climate change wreaks planetary havoc. Welcoming a packed audience, BAK director Maria Hlavajova described her reaction when she learned of the institution’s fate: “The question spinning in my head, ‘How can we be more?,’ filled me with a sense of possibility, against all odds.”

That unshakable hope mirrored the will of artists, activists, cultural workers, theorists, and organizers who gathered in an aqua-carpeted “immersive diorama” to imagine ways of propagating radically egalitarian futures in an increasingly asymmetric present. Designed by Staal to invoke the Neoproterozoic Era’s Ediacaran period, described by geologist Mark McMenamin as a “pre-socialist socialist ecology,” giant painted biota adorned wood-frame podiums and stands around the auditorium, with larger specimens bearing the heads of historical revolutionaries like Ho Chi Minh, Eleanor Marx, and Thomas Sankara, to visualize the deep time of collective struggle.

As noted in Staal’s 2022 video essay …

February 7, 2025 – Review

Augustas Serapinas’s “Pine, Spruce and Aspen”

Michael Kurtz

As much arsonist as archivist, Augustas Serapinas takes an irreverent approach to remnants of the past. In 2012 he transformed student artworks discarded at the Estonian Academy in Tallinn into strange-looking gym equipment. For the inaugural exhibition of his London gallery Emalin in 2016, he repurposed materials left by the locksmith who previously occupied the building to create a functioning sauna. And in 2018 he invited children of workers from a decommissioned nuclear power station in his native Lithuania to create a sculpture using rubble from the Soviet-era site. In each fraught context, he intervenes with light-hearted acts of creative destruction, fostering new forms of sociability and use value rather than worshipping at the altar of cultural heritage.

An ongoing strand of Serapinas’s practice involves acquiring and pulling apart dilapidated log-and-shingle buildings, reconfiguring and sometimes charring the scavenged materials, then presenting them in exhibition spaces. Examples of this architectural vernacular survive from as long ago as the nineteenth century in Lithuania as well as over the border in Poland and Belarus. They are prevalent in and around the Polish city of Białystok and feature throughout his current show, filling the Galeria Arsenał elektrownia with the musky smells of damp wood …

February 6, 2025 – Review

Michael Asher

Travis Diehl

Would you pay to have less property? Patrons of Michael Asher did. In 1979, collectors Elyse and Stanley Grinstein commissioned him to make a work for their Brentwood home, adding to a semiprivate showcase that included arrangements of yellow stripes by Daniel Buren and huge redwood logs by Richard Serra. Asher’s untitled piece stipulated that a section of a wall marking the property line be demolished and rebuilt eleven inches inwards, effectively ceding a notch of yard to their neighbors. The work couldn’t be moved or sold.

Asher, who died in 2012, may seem like one of the drier conceptual artists of his generation. His work was usually temporary and survives largely through documents and writing. His most famous pieces involved removing the front wall of a gallery or rebuilding every temporary wall ever installed in a museum. Yet a current survey at Artists Space, despite comprising mostly ephemera including printed matter, notes, and schematics (such as architectural plans for the Grinstein’s modified wall), captures the humor that made Asher so influential.

The Grinstein work, Asher’s only private commission, typifies the artist’s puckish approach to what came to be known as institutional critique. His site-specific interventions were often something of …

February 5, 2025 – Editorial

News from elsewhere

The Editors

The art historian Thierry de Duve has characterized Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain as a “telegram” sent out in 1917 and only properly received and understood by a later generation, among whom it inspired the artistic revolutions of the 1960s. We might think of it less as an artwork authored “by” Duchamp, de Duve proposes, and more as a communication “from” him to artists of like intelligence and temperament, the majority of whom had yet to be born. It calls to mind those “lost” early radio transmissions that, despite not having been recorded on tape, continue faintly to bounce around the earth’s atmosphere, such that they might still be retrieved—and decoded—by someone with appropriately sensitive antennae tuned to precisely the right frequency.

That works of art are missives to be broadcast into the ether or dropped into the post (without knowing when or by whom they will be read) is an idea that rewards wider application. When the present is so bewildering—has not transpired as the received communications led us to expect—it might be helpful to comb back through the correspondence to see if some crucial message was missed. Maria Dimitrova’s recently published piece on the textile designer Anna Andreeva, for instance, …

February 3, 2025 – Book Review

Kevin Killian’s Selected Amazon Reviews

Ben Eastham

What is “literature,” and how is it distinguished from criticism, gossip, promotional material? Is it contaminated or invigorated by its overlap with these other forms of writing? Might literature be both creative and commercial, and, for that matter, throwaway and timeless, autobiography and fiction, local and universal, critical and compassionate, tongue-in-cheek and life-or-death? Are words on the walls of toilet stalls, on social media, on online marketplaces as worthy of the honorific as the products of the literary publishing industry? This selection of Kevin Killian’s nearly 2,400 product reviews for Amazon does not answer these questions so much as undermine the basic assumption on which they are founded: why are we so eager to ascribe value to writing according to its category, rather than attending to the writing itself?

We learn from an afterword by Dodie Bellamy, to whom Killian was married for over thirty years, that her fellow member of San Francisco’s New Narrative movement started leaving reviews on Amazon in the wake of a heart attack in 2003. A practice intended to ease his way back into writing soon became more than a means to an end, to judge by the frequency of his contributions (sometimes multiple times …

January 30, 2025 – Review

“Collective Threads: Anna Andreeva at the Red Rose Silk Factory”

Maria Dimitrova

Looking at works from an unfamiliar world, we need the world as much as the work to understand what we are seeing. When Aleksandr Deineka’s grand-scale painting Textile Workers (1927) was exhibited in the Royal Academy in London in 2017, a critic described it as futuristic, likening the female factory workers to sci-fi robots. Criticizing the acute anachronism of this interpretation in the preface of her book on Deineka, art historian Christina Kiaer acknowledged the difficulty in reading Soviet paintings today: “To our eyes, unfamiliar with images of labor, these working women are strange harbingers of an unknown future imagined from the outmoded pasts of both Communism and modernist painting.” Placing Deineka’s paintings within their original sociopolitical context, Kiaer’s aim was to restore their legibility beyond the “prevailing visual codes of capitalism” and reveal something often lost on contemporary eyes.

A similar reconstructive logic underpins the first retrospective of Soviet textile artist Anna Andreeva, curated by Kiaer at the Museum of Modern Art-Costakis Collection in Thessaloniki. Lauded in the USSR, including with the prestigious Repin Prize for lifetime achievement in 1972, Andreeva was virtually unknown in the West until in 2018, ten years after her death, the Museum of Modern …

January 29, 2025 – Feature

Condo London 2025

Orit Gat

“I always arrive at something new out of desperation.” This was Anna Zemánková’s description of how she began to make drawings in satin when she ran out of paper. The resulting collages use textile colors, ballpoint pen, and acrylic to create the shapes of flowers and plants. They are tender and surprising, a new and shimmering nature. Zemánková, born in Austria-Hungary in 1908, was self-taught: a dental assistant who began making art after a bout of depression following the death of one of her children. Drawings of flowers might traditionally be defined as “women’s work”; better to say that it was the conditions under which she made art—pressured to take a trade rather than go to art school, raising a family, only making work as a response to personal tragedy—that defined her labor as such.

Eight of Zemánková’s flower pieces, which were also shown at the 2013 and 2024 editions of the Venice Biennale, were brought to London by Sophie Tappeiner as part of Condo, a project in which twenty-two London galleries host twenty-seven peer spaces from around the world. The match-ups vary. The Approach handed their annex space to Vienna’s Tappeiner and their upstairs to Zurich gallery Philipp Zollinger, …

January 24, 2025 – Review

Cihad Caner’s “(Re)membering the riots in Afrikaanderwijk in 1972 or guest, host, ghos-ti”

Musoke Nalwoga

In August 1972, a Turkish landlord evicted a Dutch woman living in the Afrikaanderwijk neighborhood of Rotterdam. This event became the trigger for riots which saw people from all over the country pour into the Afrikaanderwijk to watch as anti-immigration protesters destroyed homes in the majority-immigrant neighborhood. Ten years ago, the Turkish artist Cihad Caner moved to Afrikaanderwijk. Having happened upon the story of this riot, he attempted to reconstruct a collective understanding of its history with his 2023 film (Re)membering the riots in Afrikaanderwijk in 1972 or guest, host, ghos-ti.

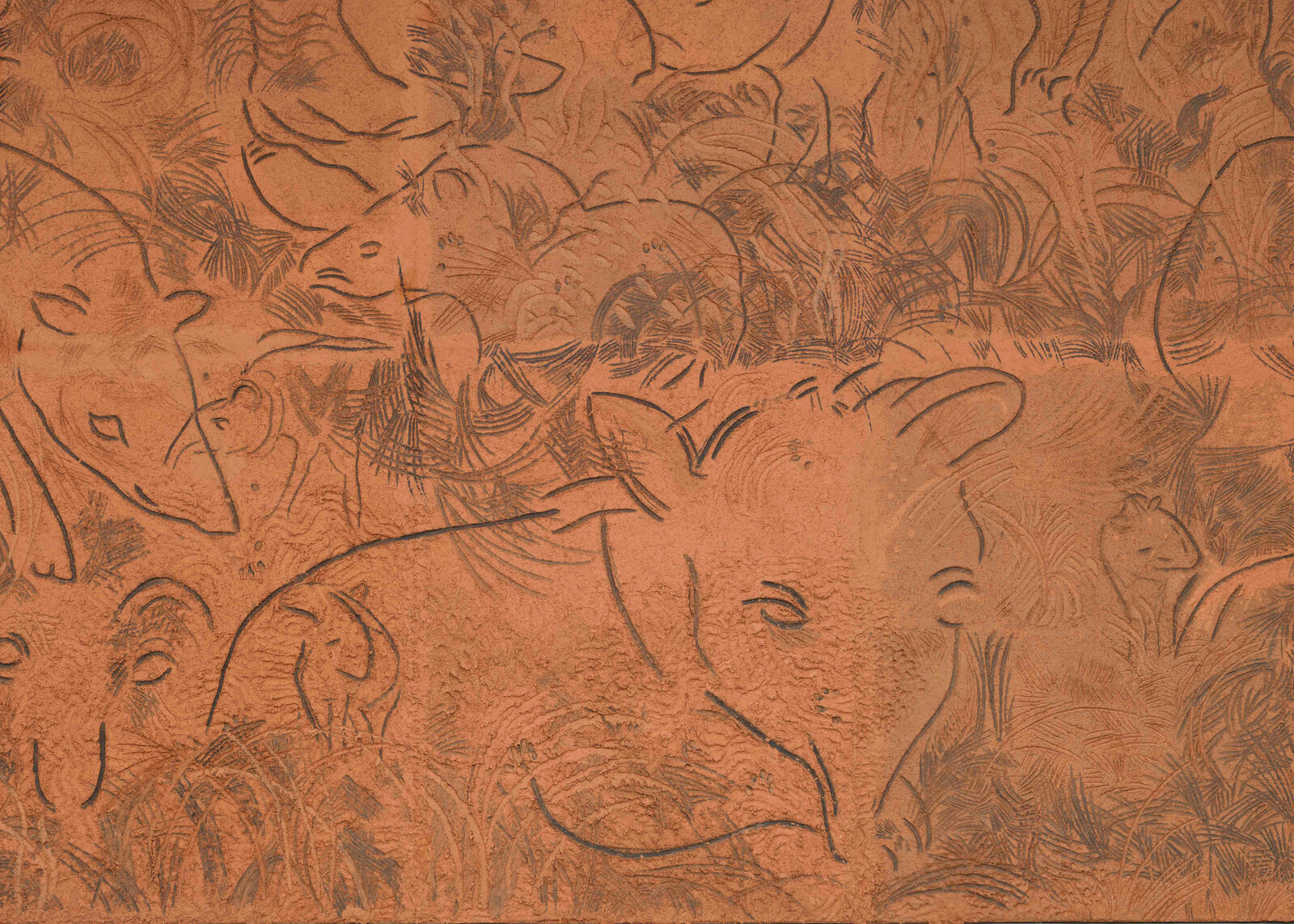

The exhibition is sparse. A white room is scattered with archival images scratched into red MDF plates. Inscribed into some of the plates are scenes showing people rioting on the streets of Afrikaanderwijk; others show the inside of immigrant homes that are visibly looted and in disarray. With this simple gesture, Caner places the Dutch rioters as the outsiders on the streets and the immigrant workers as the insiders in their homes—probing the latter’s status as outsiders in the Dutch collective psyche. The viewer, meanwhile, is made to oscillate between being on the inside and the outside as they navigate the installation.

Caner is an artist of Turkish descent, …

January 23, 2025 – Feature

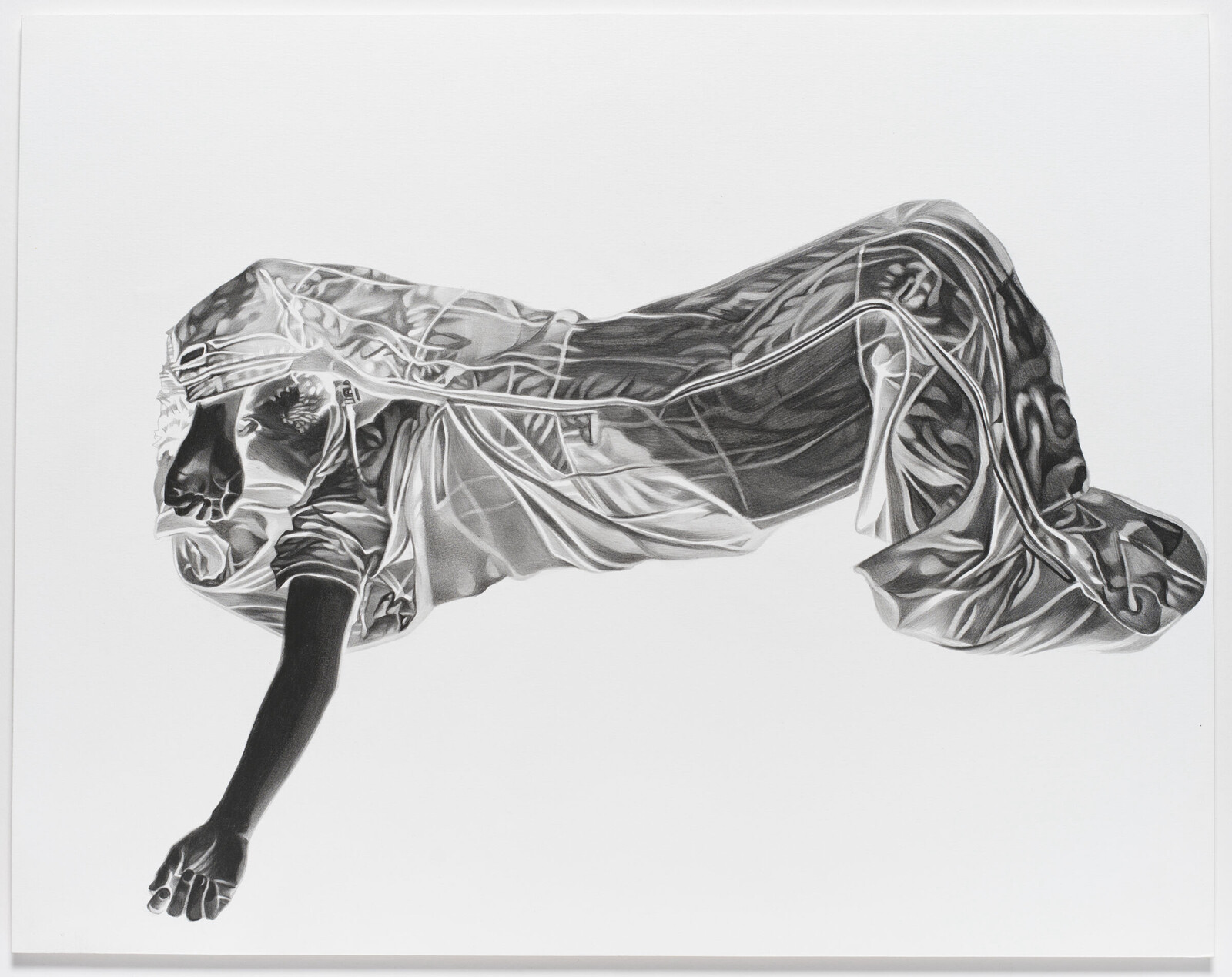

On Nolan Oswald Dennis

Sean O’Toole

Over the past three years, Nolan Oswald Dennis has gained significant international recognition, showcasing their diagrammatic and collaborative practice at two prominent Swiss museums in 2024 alone. The artist’s probative, sometimes opaque work—a mix of drawing, sculpture, film, and installation—also appeared in recent editions of biennales in Dakar, Liverpool, São Paulo, and Shanghai. These career milestones were bookended in late 2024 by an event closer to home: the artist’s first museum solo exhibition in South Africa. Organized by Cape Town’s Zeitz MOCAA, “Understudies” offers a broad overview of Dennis’s multifaceted practice, its speculative methods, iterative processes, rootedness in collaboration, and overall inclination towards “keeping a question open for as long as possible,” as the artist put it to me during a series of online conversations and email exchanges.

Curated by Thato Mogotsi, Dennis’s early-career survey includes small drawings on grid paper, variously sized hard and soft sculptures portraying globes (a recurring motif in their practice), a low-tech receipt printer issuing aphoristic chunks of text by anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko, as well as a drawing installation depicting a celestial body. The selection affirms the importance of models, diagrams, annotations, and simulations as forms for prompting critical thinking. Partly inspired by the …

January 22, 2025 – Review

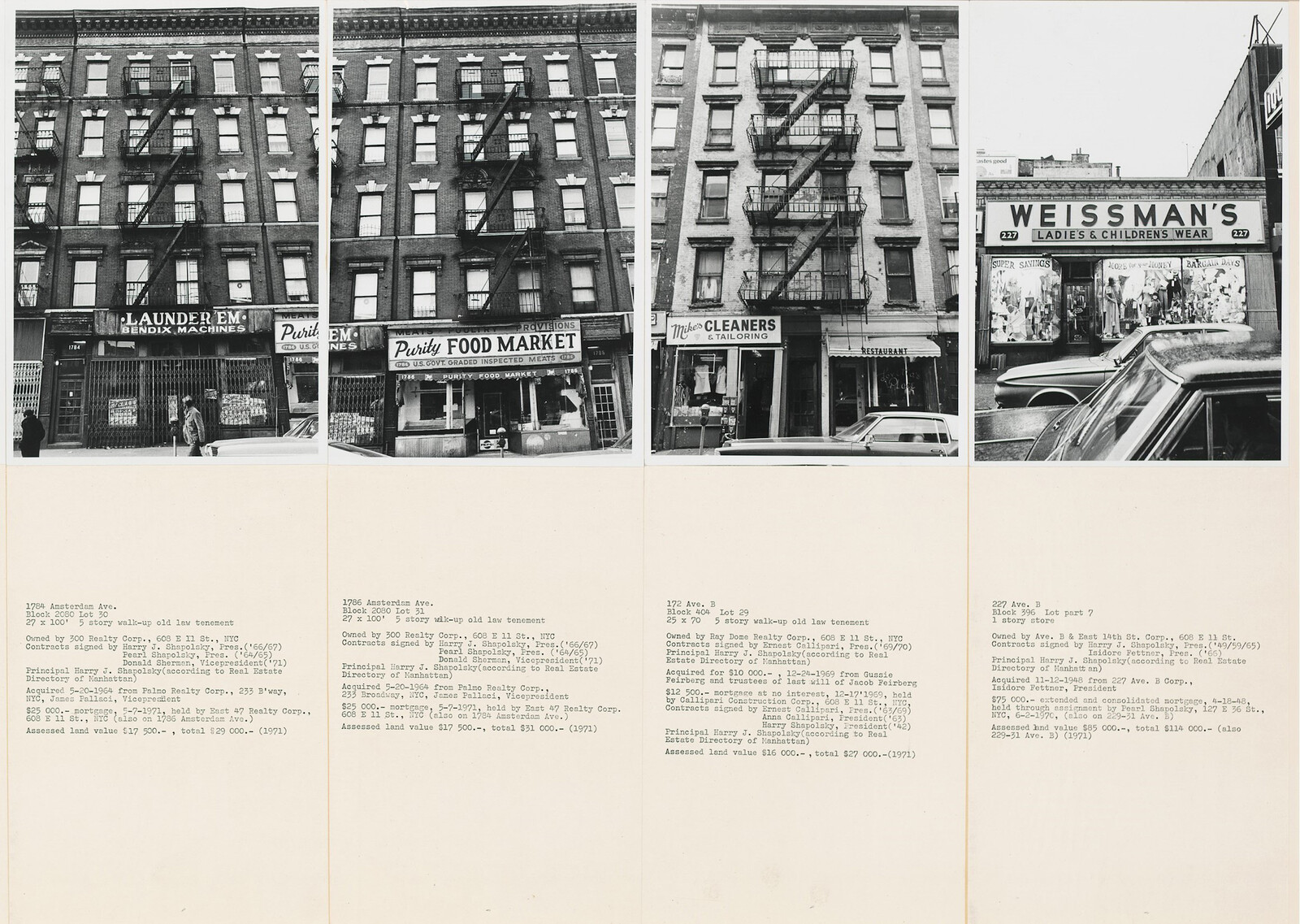

Hans Haacke’s “Retrospective”

Jörg Heiser

If you had never encountered Hans Haacke’s work before, then you might think, upon entering the first room of this exhibition: “Oh nice, look! How pretty and interesting. There are his op art-influenced canvases of the early 1960s, and the physical and organic systems (balloons floating, plants growing) of later in the decade.” In the next space, you might think: “Holy moly! Something must have happened around 1969/70, that guy really had a moment of political awakening—look how fiercely he’s attacking the powerful in the art world.” At which point a Haacke expert might pop up and tell you that of course there is a peculiar, logically imperative connection between those earlier experiments in form, system, and process and the later work that would become the paradigmatic form, system, and process of institutional critique. This expert would have a point. But the desire to always explain that connection as a logically inevitable and linear one is also a bit suspicious and needs to be probed—for which this retrospective (which travels to Belvedere, Vienna) is a welcome occasion.

The above thought experiment would not happen in actuality—before stepping foot in the first room, you have already encountered two later works—and so the …

January 17, 2025 – Feature

Value in, garbage out: on AI art and hegemony

R.H. Lossin

In 2023, Refik Anadol launched the digital artwork collection “Winds of Yawanawa.” In collaboration with the Yawanawa people of Brazil, Anadol collects data from the Brazilian rainforest and combines it with drawings by Yawanawa artists to create 1,000 AI-generated NFTs that can be purchased with Ethereum. This massive undertaking is intended to “protect the Amazonian rainforest” by “preserving and uplifting Indigenous modes and models of environmental protection and sustainability.” Anadol, who’s made a name for himself championing the use of artificial intelligence as a new “pigment,” has largely organized his practice around environmental crusades. In 2024, his AI-generated portrayal of coral reefs Large Nature Model: Coral—a work which, according to an official United Nations press release, “offers an unprecedented glimpse into the vastness and complexity of our oceans”—debuted at the UN as part of a sustainability initiative. In addition to centering the Yawanawa through data collection and transforming coral reefs into two-dimensional, undulating masses of color, Anadol is broadly engaged in using AI to represent our natural environment in a bid to reimagine and save not just coral reefs or tropical rainforests, but “the future.” What is going on?

“Hegemony,” wrote Raymond Williams, “is the continual making and remaking …

January 16, 2025 – Review

“Admired, collected, and put on display”

Kenny Fries

Many museum exhibitions—and re-hangings of permanent collections—have in recent years aimed to address legacies of colonialism, as well as outdated and oppressive gender and sexual “norms.” Sometimes these shows incorporate contemporary art in response to historical work now viewed as pejorative or oppressive. Too often forgotten in these re-visions of art/history is the stereotypically dehumanizing representation of disability and disabled persons. “Admired, collected, and put on display,” in the Baroque treasury of the Dresden Residenzschloss, attempts to rectify this glaring omission by employing the work of contemporary disabled artists to provide critical context to such royal collections, as well as to render more fully the history of disability representation.

This curatorial goal is crucial yet its enactment is problematic, often re-inscribing this dehumanizing history. Attempts are made to mobilize the contemporary art to demythologize disability, but the historical works and what they promulgate dominate contemporary pieces by Eric Beier Eva Jünger, Steven Solbrig, and Dirk Sorge, which are placed mostly outside the small exhibition room or, in the case of Beier’s work, used more as a structural crutch rather than integrated critique.

Floor guides provide access for visitors who are blind or have low vision. But in the spacious covered …

January 15, 2025 – Review

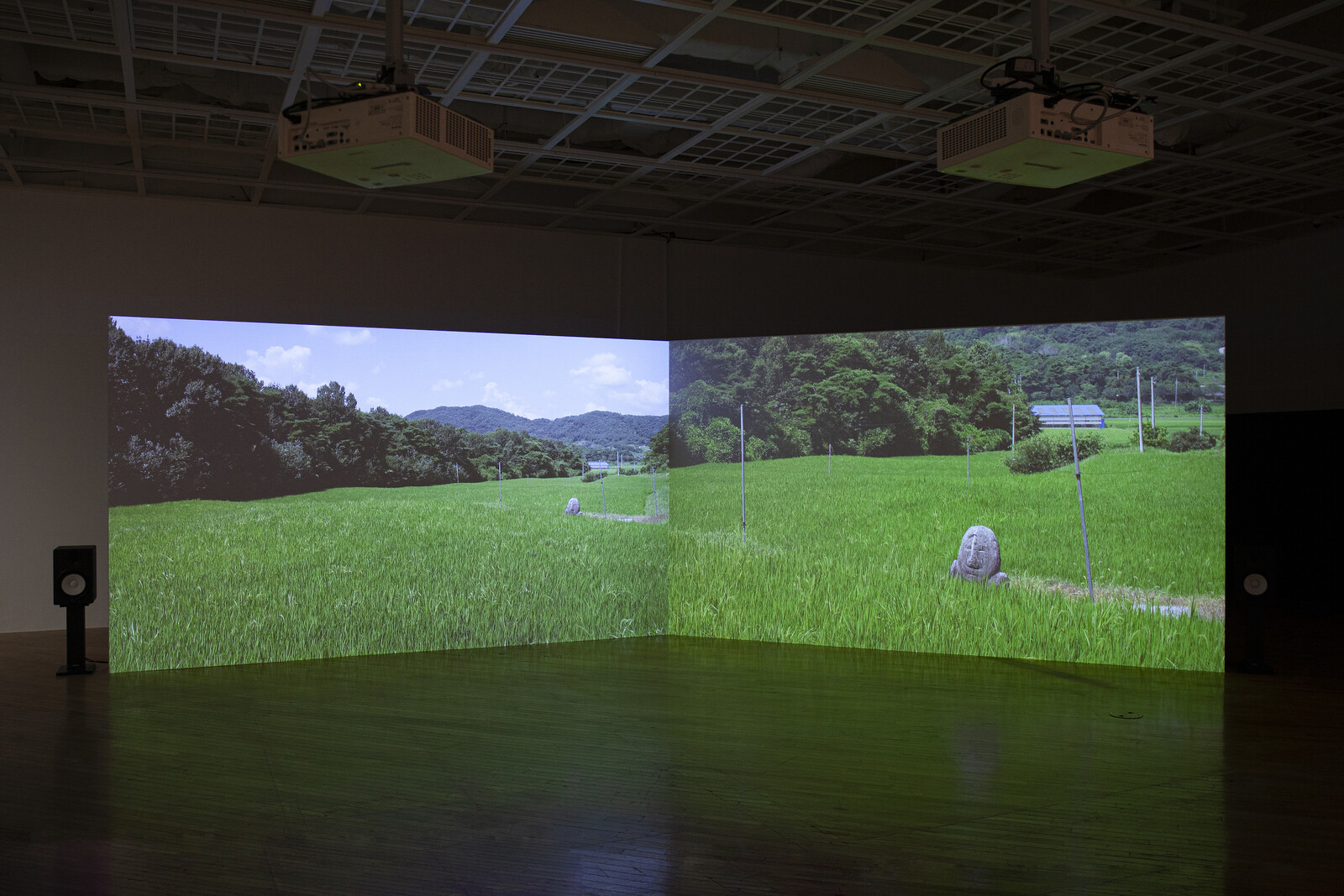

ikkibawiKrrr’s “Rocks Living in Rewind”

Hallie Ayres

Robert Hazen outlined the theory that the mineralogy of planets and moons evolves as a direct result of interactions with life. While only a dozen mineral species are known to have existed when our solar system formed 4.6 billion years ago, today Earth plays host to more than 4,400, an indication that the chemical and biological processes enacted by organisms engender their formation. On a planetary geology scale, then, our interactions with rocks stimulate their development as much as they buttress ours.

This molecular symbiosis threads through the works in ikkibawiKrrr’s solo exhibition at Art Sonje Center. Since 2021, the trio—composed of Cho Jieun, Ko Gyeol, and Kim Jungwon—has explored the interactive and shifting boundaries between humans and the nonhuman natural world. The collective’s name comprises “moss” and “rock” in Korean, plus the onomatopoeic sound “krrr.” While previous bodies of work have centered on seaweed, grass, and moss, “Rocks Living in Rewind” sees the group hewing to that more abrasive component of their appellation, through a sustained focus on the South Korean peninsula’s disregarded stone statues of Maitreya–the bodhisattva believed to embody the future Buddha.

Visitors are greeted by Buddha High Five (all works 2024), a cement hand, larger than …

January 10, 2025 – Review

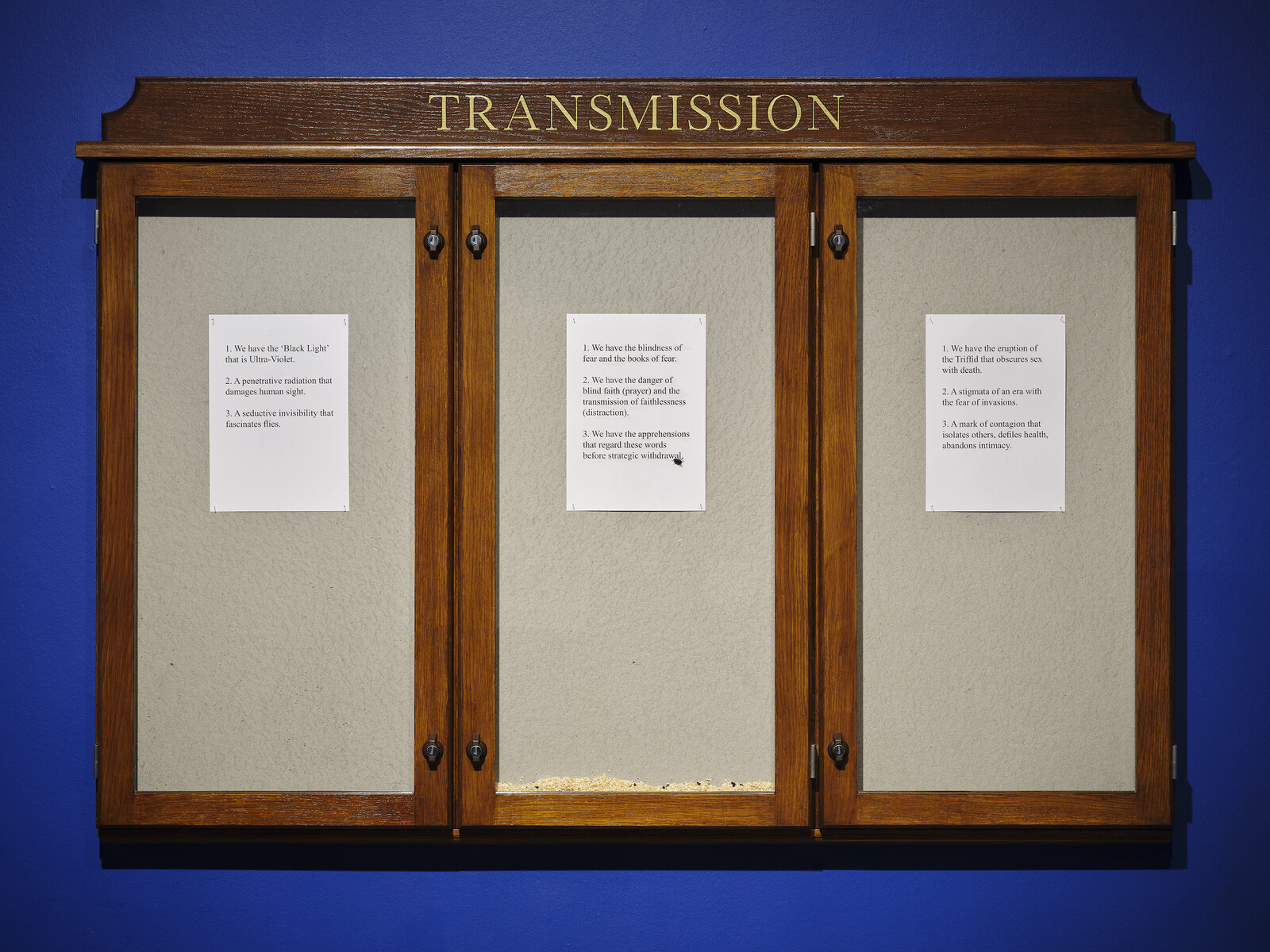

Hamad Butt’s “Apprehensions”

Tom Denman

Hamad Butt’s long overdue first retrospective opens with what might as well be a statement of unfinished business. A noticeboard headered with the word “TRANSMISSION” houses behind its glass doors a colony of live flies; pinned to the board are three sheets of A4 paper printed with tercets canticulating blindness, fear, contagion, and the obscuration of sex with death. Transmission (1990)—a chilling installation revolving a prayer circle of glass books splayed on the floor on parabolic legs, with the pages resembling wings, and the potentially blinding ultraviolet lights acting as spines, or thoraxes—is Butt’s first concrete response to the AIDS crisis, spurred by his own HIV-positive diagnosis in 1987, the same year he enrolled, aged twenty-five, at Goldsmith’s College in London. It was the focus of his degree show in June 1990, a month before the former Goldsmith’s student Damien Hirst exhibited his raucously acclaimed, also fly-infested A Thousand Years (1990). Presumably interpreting Hirst’s piece as plagiarism, Butt revoked the flies from his own installation and the original noticeboard has long been lost. Although the wall text omits this controversy, the curators have honored the artist’s decision by showing the refabricated component separately, presenting the rest of the installation in …

January 9, 2025 – Review

Antonio Obá’s “Rituals of Care”

Kaelen Wilson-Goldie

In September 2019, an eight-year-old girl named Ágatha Vitória Sales Félix was shot and killed by police in Rio de Janeiro as she was riding home in a small public bus with her mother. The officers argued that they had been fired upon first, and moreover, that they were in the midst of a wider war, part of the former Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro’s “30 bullets for every bandit” crackdown on crime, during which nearly a third of all violent deaths in Brazil’s second largest city came at the hands of the state. Witnesses countered that there had been no such shots, and rather, that the officers, unprovoked, had targeted an unarmed motorcyclist, and missed. Ágatha Félix was shot in the back and rushed to a local hospital, where she died. Reportedly, police then raided the hospital to try and retrieve the stray bullet that had killed her, lest it be used as evidence against them, but were unsuccessful. Within days, protests erupted across the favelas of Rio, where Ágatha was born and raised.

That same year, the artist Antonio Obá painted a harrowing group portrait of thirteen small boys crowded together behind a table piled …

January 8, 2025 – Review

“OTR^S MUND^S”

Gaby Cepeda

In 2020, the group exhibition “OTRXS MUNDXS” offered a snapshot of Mexico City’s young artists and collectives. Whereas that first show felt overly ambitious, occupying the whole of Museo Tamayo and adopting a theoretical framework that attempted to define a generation, the latest iteration goes in the opposite direction: abbreviated to a few galleries and the central patio, and lacking any coherent sense of structure. The memorable (and sizable) installations by individual artists that were a feature of the first show are here replaced by a more scattered approach that conceives of the museum as a musical instrument, to the detriment of the art displayed within it.

The exhibition begins in the central patio, where a MIDI-controlled pianola has been programmed to play Conlon Nancarrow’s Study No. 21 (1948–60)—the piece is notorious for its intense speed and posthuman notation—once every hour. On my visit, however, it wasn’t working. Two sculptural speakers nearby played a combination of music, sounds, and noise selected by three radio collectives: Radio Noche, Radio Nopal, and Radio Imaginario. Abraham González Pacheco’s Windborne Message (2024), a series of beige polyethylene curtains hanging at different heights and embroidered with fists, roses, and scribbles, offered a scenography of sorts. …

January 7, 2025 – Editorial

Years that ask and answer

The Editors

Art criticism operates with a time lag. If you accept that art is shaped by the historical contexts in which it is made, then the critic must always be writing after the fact: after all, it takes time for the artist to make the work, it takes time to organize the exhibition, and then it takes time to write the review of that exhibition. Even a work made expressly in response to a specific event might not come to be written about until weeks, months, or years have passed. By which time the world might have moved on, the calamity been forgotten, the government deposed, attitudes shifted.

Yet this might be the great advantage of the form. However frustrating it can be that criticism must trail behind the news, this means that it also resists the violently unstable model of history that a hyper-accelerated and functionally hysterical media cycle propounds. Criticism narrates an encounter with the past (whether near or distant) and with other perspectives. It depends on a belief in continuities and commonalities, which is to say a commitment to the principle that the past carries meaning in the present, and that every other person’s experience of the world …

December 23, 2024 – Review

“The Imaginary Institution of India: Art 1975–1998”

Serubiri Moses

Sheba Chhachhi’s photographs, taken on the frontline of the Indian women’s movement—crisp black-and-white images of working-class women at a demonstration, performing in a play about gender-based violence, and in their own homes—encapsulate this watershed exhibition well. “The Imaginary Institution of India”—which includes over 150 works of painting, sculpture, photography, and other media, sprawling over two floors and thirteen sections—is a show about class and its tensions, playing out violently in the world’s largest democracy. Curator Shanay Jhaveri’s thesis, though, rests on the formal and aesthetic shifts as shaped by the politics of this time period (1975–98). For Jhaveri, developments in landscape painting, for example, illustrate the ways in which class tensions came to a head after the declaration of Emergency in 1975.

Writing in March 1987, artist Anita Dube asked whether the incumbent Indian nationalist and mainstream political discourse could view the lower caste person and petit bourgeois artist as a “species being who creates history.” “A sleepless wind is raising a sleepless song in sleepless heads in sleepless nights,” wrote Dube at the end of her text. Reading it, I paused on every sleepless, and again at sleepless nights. If sleepless nights paint a picture of …

December 19, 2024 – Review

“MuMoToMo”

Adeline Chia

Collectives have played an influential role in the history of Indonesian art, from the 1930s, when the twenty-member PERSAGI, or Persatuan Ahli-Ahli Gambar Indonesia (Union of Indonesian Painters), boldly declared a nationalist, anti-colonial agenda, to the now-famous ruangrupa, whose methods of resource-sharing and knowledge-building have become influential touchstones for a more egalitarian art world.

In contrast to these collectives associated with political and social action, this exhibition features an informal group of four artists from or based in Bali—Edmondo Zanolini, I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih, Dewa Raram and Dewa Putu—whose concerns are profoundly personal and inward-looking. In the 1990s, they formed a commune-like group (some of them lived together) where they made art and formed a space to explore their fantasies, trauma, and subconscious. Although the styles of their output were very different, their works displayed similar motifs and subject matter, which could come from specific visual prompts (like photographs) which they used to stimulate creativity, or a more spontaneous process. The resultant body of work on show here are the strange, fascinating fruits of their collective dreaming.

“MuMoToMo” is an abbreviation of the artists’ names. The “ringleader”—whose house formed the gathering-place for this group—is Edmondo Zanolini …

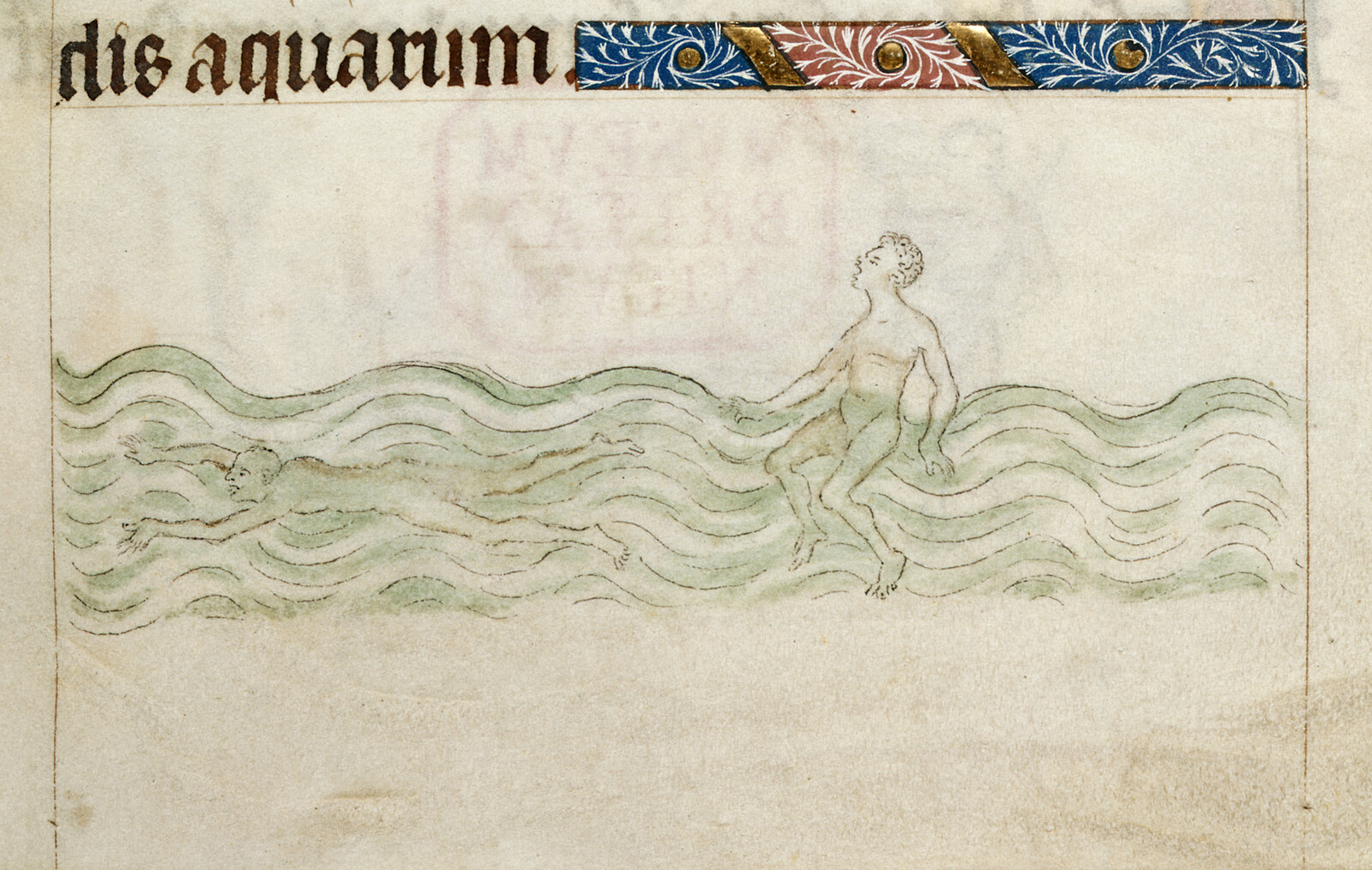

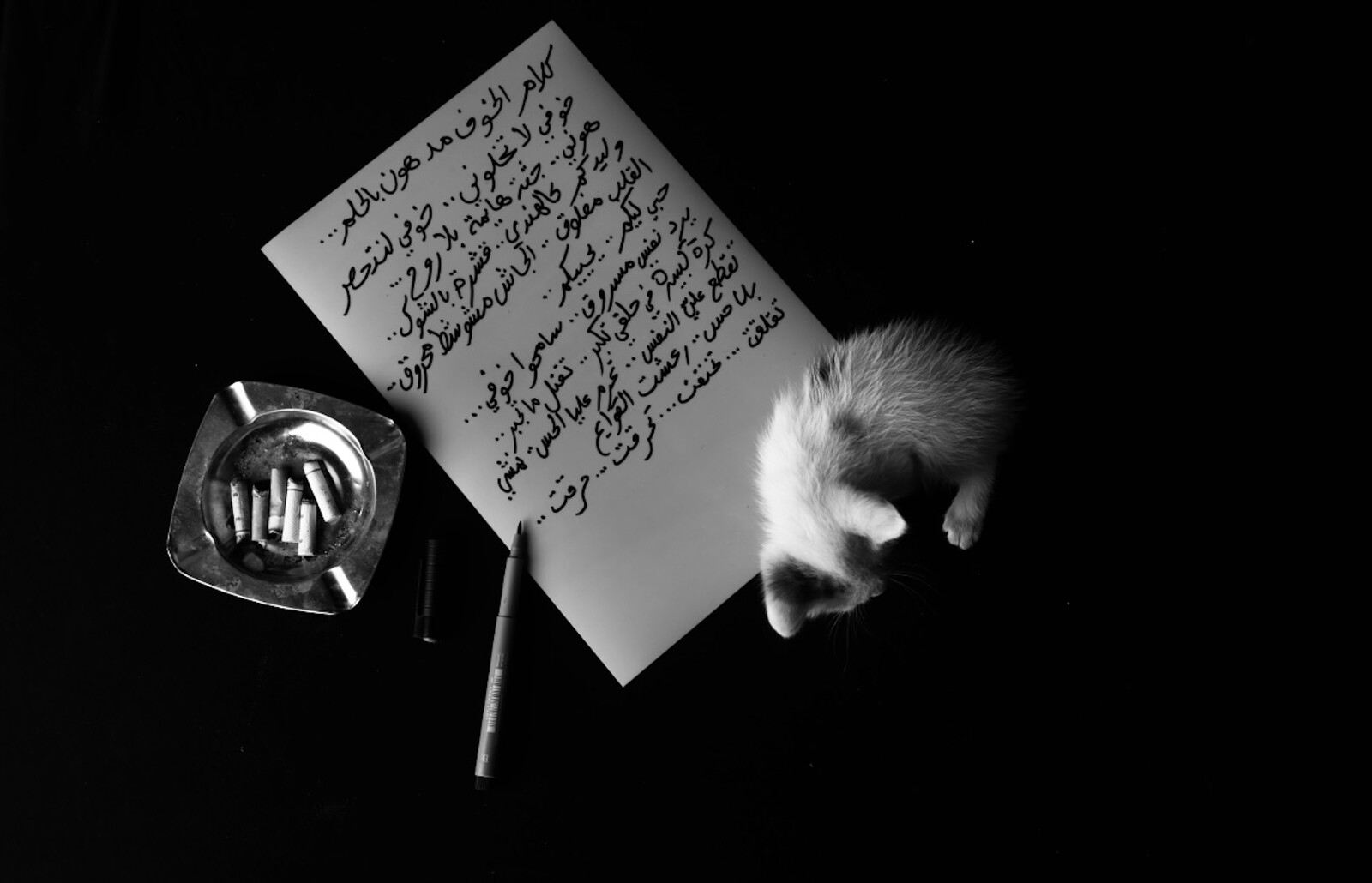

December 17, 2024 – Review

Jaou Tunis 2024

Stephanie Bailey

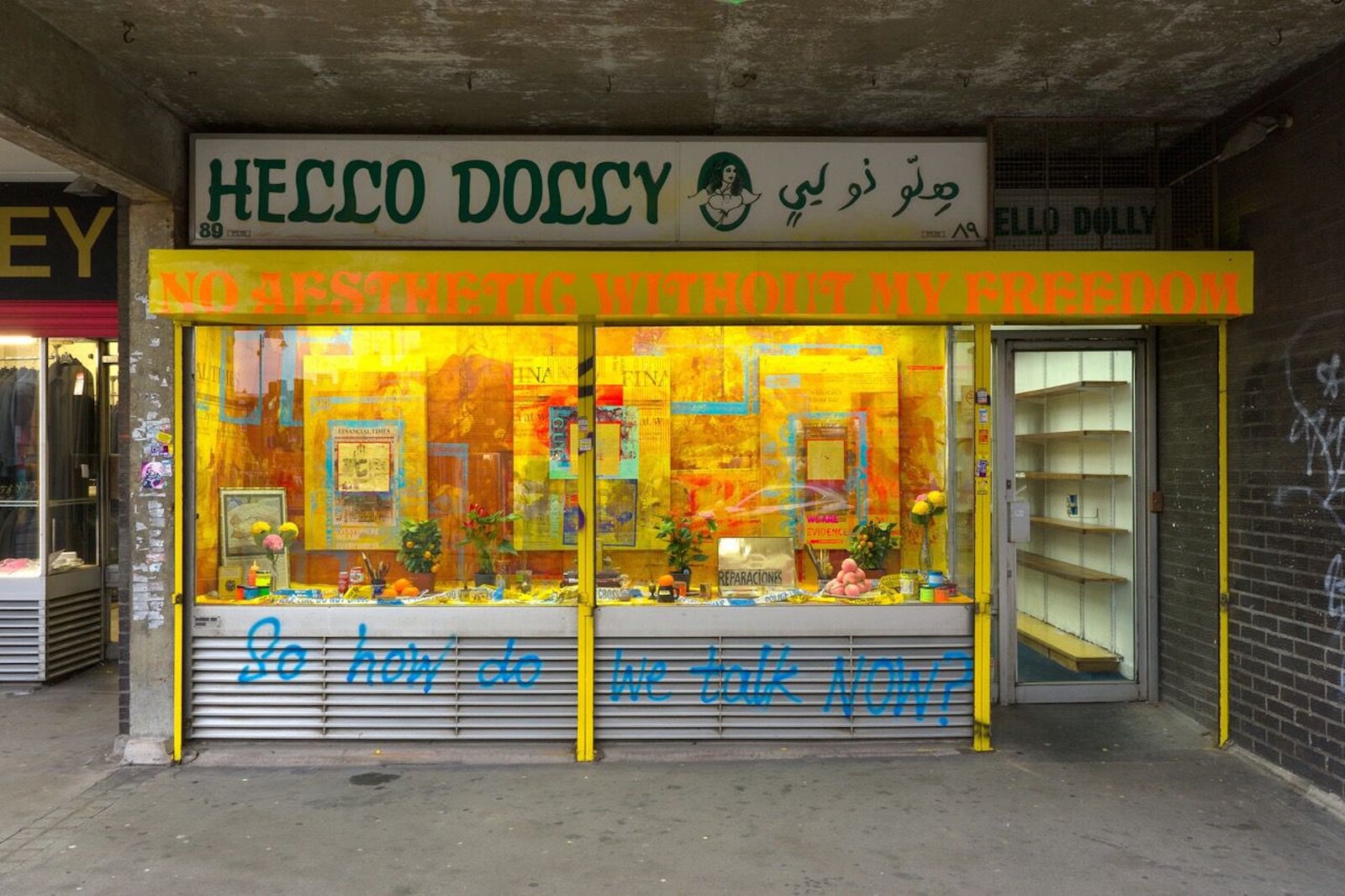

If there was one exhibition that tapped into the Tunisian zeitgeist during Jaou, the contemporary art biennial organized in Tunis by the Kamel Lazaar Foundation, it was “Hopeless.” Curated by Chiraz Mosbah on the grounds of Club Aviron Tunisois, with storehouses for kayaking and rowing perched on the edge of the water, the show references a desire among many young Tunisians to leave the county, given its struggling economy and increasing authoritarianism, and its position as a crucial crossing point for clandestine migrants. Still, works by some forty photography students from sixteen academic institutions in Tunisia, who collaborated on the curatorial design and theme, expressed a commitment to place in their staging across the site’s closed and open spaces.

In one room, Last Words (2024) by Souhir Ben Abdallah consisted of a black-and-white photograph of a letter by a young man describing his fear of being trapped, ostensibly explaining his desire to leave the country, and an audio recording of his words being read aloud. In an adjacent space, where images were viewed using flashlights in the dark, photos by Dhia Guermit were installed amid stored oars, including one showing a trio launching a rowboat into the sea. Nearby, a …

December 16, 2024 – Review

Mohamad Abdouni’s “Soft Skills”

Crystal Bennes

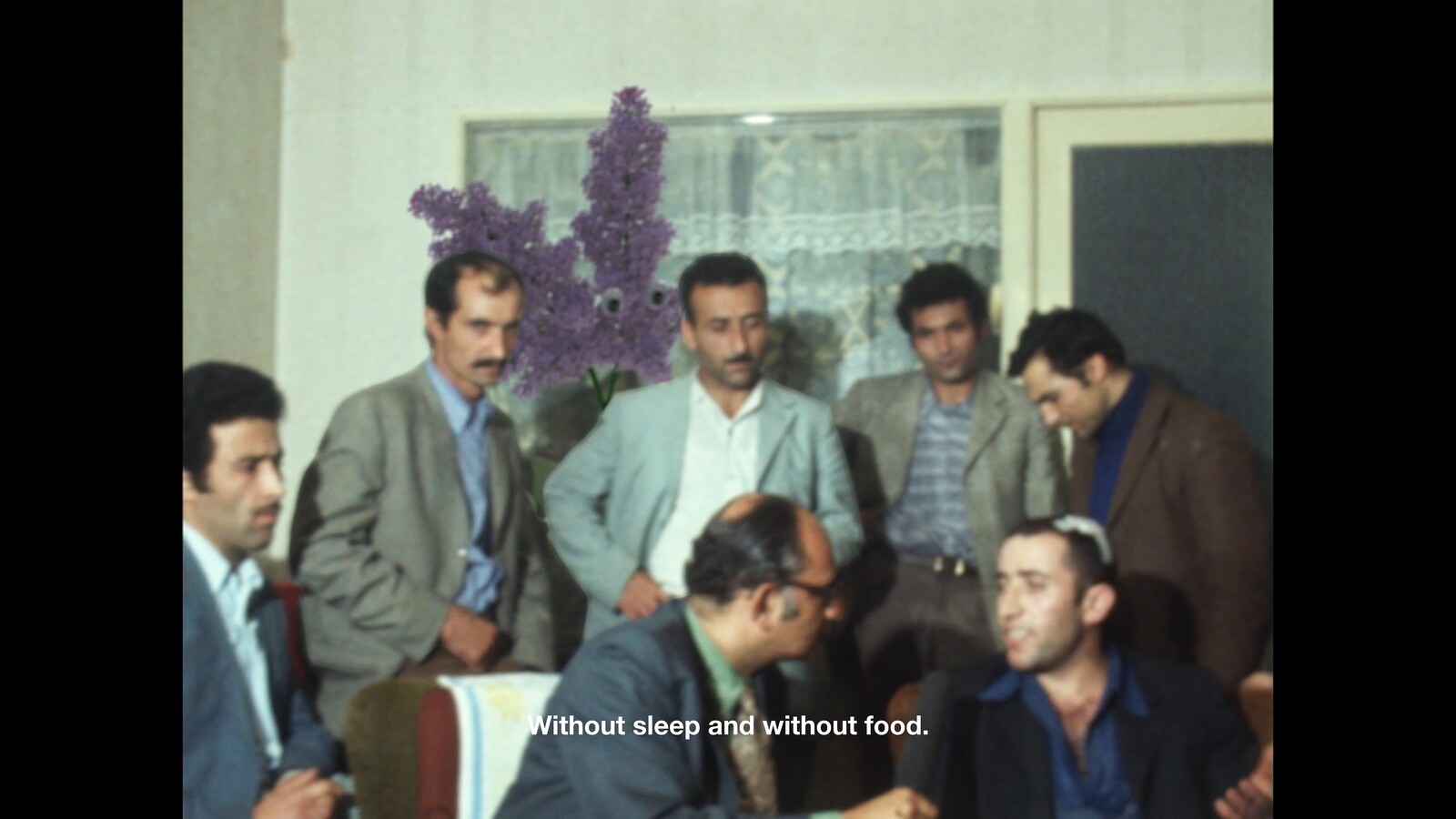

“I’ve always been obsessed with losing my memory because it’s something that runs in my family,” Mohamad Abdouni remarked last year. Long a driving force of his practice, photography has allowed him to excavate, reinvent, and remember queer histories in Arab cultures. Here Abdouni shifts view to his home region of Beqaa, Lebanon. In pulling apart family photo albums, subjecting them to the scrutiny of his loving but unsentimental gaze, the artist returns to his childhood navigations within the complex cultural norms of a heterosexual masculinity and male camaraderie that embody Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s theory of “male homosocial desire” grounded in anti-queerness.

The exhibition’s title refers to other types of skills soldiers might be required to demonstrate outside mastery of arms. In Abdouni’s hands, time-worn family images become soft evidence, pointing to the ways in which a child’s queerness resisted masculine norms and strained interfamilial relationships. A father gazes, disapprovingly perhaps, towards a little boy posing cross-legged in a green plastic chair (How to Properly Sit on a Chair, 1996). “Straighten your screws,” Abdouni was told as a child. Act like a man. Yet, the deliberate selection of images here—mostly of men, mainly Abdouni’s father—disrupt stereotypes of Middle Eastern men …

December 13, 2024 – Review

Francis Alÿs’s “The Gibraltar Projects”

Alan Gilbert

Voters in Western countries have consistently repudiated neoliberalism for more than a decade. They have done so in tandem with a rise in anti-immigration politics: reactionary populism that wants locked gates on national borders and larger regions, such as the Mediterranean and Central America, while simultaneously despising cultural gatekeepers. “The Gibraltar Projects” is a new restaging of material made in 2007 and 2008 devoted to the Strait of Gibraltar, and it is possible to imagine that the decision to exhibit the work in tandem with the recent US presidential election—in which both candidates focused heavily on immigration—might be seen as a form of critical and/or political commentary, depending on how one defines those terms. A globetrotting artist, Francis Alÿs came of age in the 1990s when, in the wake of the Cold War, the high end of the art world aspired to an ethical yet pleasurable cosmopolitanism mirrored by a new movement of people and goods accompanying the rapid spread—and imposition—of free market economics.

Over the decades, Alÿs’s art has increasingly focused on children. And while some of this work is situated in refugee camps and war zones (for Documenta 13 Alÿs repeatedly visited Afghanistan, over four years), one begins …

December 12, 2024 – Review

38th Panorama of Brazilian Art, “Mil graus”

Juan José Santos

The Tupi people roasted their prisoners on a grill called a “moquém” before eating them in anthropophagic rituals. Frederico Filippi’s Moquém - Carnes de caça (2023–24) presents the fragments of two tractors incinerated during a Federal Police raid in Itaituba, Pará, on just such an iron grid. The installation riffs on interrelated struggles—people versus machines and among themselves, and machines against each other—to produce an absurdist allegory on the suicidal nature of certain forms of “progress.” Nearby, Zimar’s jesting zoomorphic masks, Careta de Cazumba (2024), traditionally worn in parades and here made from found materials, such as motorcycle helmets, PVC, rubber, wigs, or animal bones, appear to be mocking Fillipi’s charred materials. Zahỳ Tentehar’s short science-fiction video Máquina Ancestral: Ureipy (2023), on the opposite wall, shows the artist wandering through a ruined factory in the jungle. This triad of works proposes a critical reading of excessive industrial ambition, and of the relationship between ancestral Indigeneous traditions and capitalism. They represent the boiling point of this heated 38th edition of Panorama, the biennial temperature-check of Brazilian contemporary art.

Panorama is inextricably linked to the Museu de Arte Moderna (MAM), and has nurtured the institution’s collection since its inception in 1969. This …

December 10, 2024 – Review

Y. Malik Jalal’s “Break Neck Speeds”

Jenny Wu

Y. Malik Jalal’s steel sculptures serve as picture frames for his found photographs. Newspaper clippings, magazine covers, business cards, and screengrabs from traffic camera footage, once incorporated into the New Haven- and Atlanta-based artist’s somber color palette and subjected to his arrangements and juxtapositions, evoke an aesthetics of abjection, conjuring car accidents from which one cannot, despite one’s better judgment, look away.

In the wall-mounted assemblage WARP NO. 1 (all works 2024), a large print of the dented front bumper of a gray jalopy looms over a much smaller black-and-white photo of a veiled Princess Diana. In light of this juxtaposition, the high-speed collision that fatally injured the English royal in 1997 seems prefigured in her downcast eyes. Both images are set in a flat, steely-gray frame that, like the old car, appears scuffed, dusty, and dilapidated but not quite vintage—decommissioned but unable to rest. In WARP NO. 2, Jalal presents an image of a crash test dummy strapped in the backseat of a car. At the bottom right of the panel, positioned like addenda, are a grimy red lens cloth advertising Harrigan Inc., a Connecticut-based home and auto insurance agency, and a photo of an actor’s face covered in …

December 6, 2024 – Book Review

Iola Lenzi’s Power, Politics and the Street

Max Crosbie-Jones

In December 2013, visitors to the Bangkok iteration of “Concept Context Contestation: art and the collective in Southeast Asia,” a traveling show curated by Iola Lenzi, took pictures against a hand-painted photo studio backdrop inspired by old Saigon, played ping-pong on a circular table, photocopied pages of politically charged Indonesian comics, and wrote down in a notepad what they would do if the handgun-shaped pink rice crackers piled on the gallery floor were real firearms. Coinciding with sit-ins by an anti-government pressure group on the streets outside, the show felt like living proof of the proposition fleshed out in Lenzi’s new book. The “aesthetics of agency” engendered by such works is, she argues, a coded and often covert response to historical contexts and real-world conditions in illiberal locales: a subtle form of empowerment. As a result, the western modes it is tempting to label them with (social sculpture, relational aesthetics, and so on) are a poor fit. “Art of this book,” Lenzi states near its beginning, “has a disrupting effect, priming independent thinking.”

Over the course of seven illustrated chapters, she authoritatively (if somewhat wordily) positions this hallmark within a wider reconnaissance of Southeast Asian contemporary art’s piecemeal evolution between …

December 5, 2024 – Review

Jakarta Biennale 2024, “50 Tahun Jakarta Biennale 1974–2024”

Innas Tsuroiya

Every so often in its fifty-year history, the Jakarta Biennale has catalyzed a shift (the 1974 Indonesian New Art Movement started as a protest against its conservatism) or sparked a nationwide discourse about the state of Indonesian art (as with the experimental mid-nineties iterations). More recently, changes of format and structure—the cancellation of the 2000 edition due to insufficient funds, the 2009 “internationalization” in which other countries were invited to participate, the establishment of the Jakarta Biennale Foundation in 2014, the “pandemic edition” of 2021—have reflected developments in the way that contemporary art is made and understood. This anniversary edition of the Jakarta Biennale is presented as a celebration of its history, but the question remains of what is at stake.

At the main exhibition space in the Taman Ismail Marzuki complex—one of four venues alongside Gudskul, Komunitas Salihara, and Subo—a wall text and timeline is dedicated to the artists and art workers committed to the thankless work of biennial organizing. Yet beyond the attempt to historicize the exhibition and celebrate its continued existence, little information is provided about the curatorial framework of this iteration beyond that it has been organized according to a system resembling the “lumbung” practice of …

December 3, 2024 – Editorial

A foreign country

The Editors

Every generation makes its own world. Most of us prefer our own, having been brought up in it, and must work to understand those that come before and after, much as we have to learn the customs of a foreign country in order to live rewardingly in it. Visiting—or surviving into—another’s time is similarly estranging or enlightening, depending on your willingness to engage with its unfamiliar forms and weird preoccupations.

Criticism dramatizes these intergenerational tensions. Younger writers dismiss the work of older artists as no longer fitting to a changed world; older writers dismiss new movements as shallow in their thinking, misguided in their priorities, or derivative in their strategies. These frictions between generations—like those between cultures—generate the heat and light that animate the history of art. So it has always been, so it will always be.

Such disagreements are not a bad thing; indeed, they might be the purpose of the form. Because criticism depends upon a nuance that is best articulated in practice. The reality in which we live is to some degree—it has become fashionable to point out—constructed. But recognizing that there are different ways of building does not invalidate the principles of architecture. To attempt sincerely …

November 28, 2024 – Review

Nástio Mosquito’s “King of Klowns”

Jörg Heiser

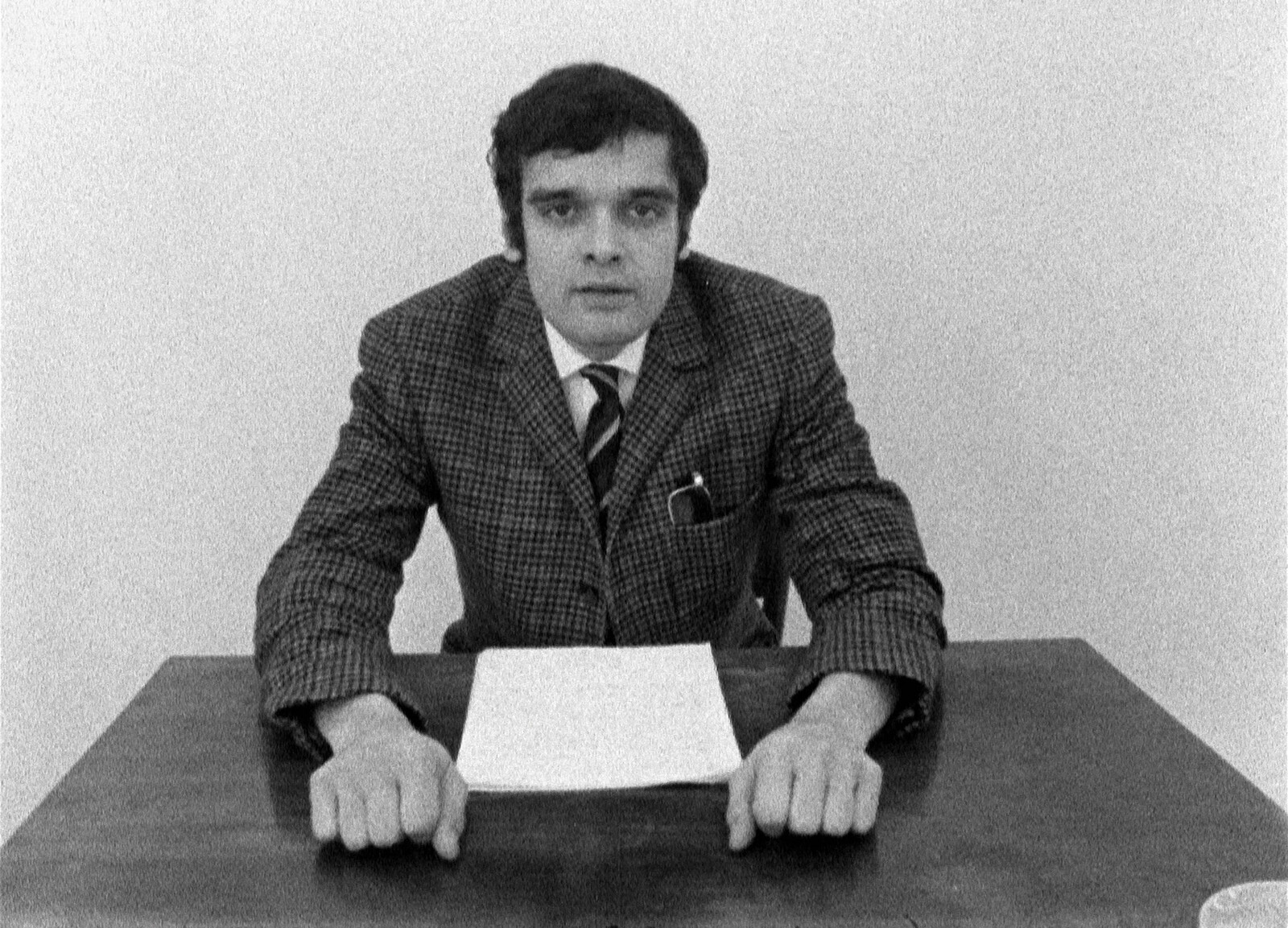

This survey of Nástio Mosquito’s work from the early 2000s to the present begins, before it begins, before it begins. This cascade of overtures starts in the entrance hall of M HKA, which doubles as a reading room. In front of one of the bookshelves, a small cubicle monitor sits on a plinth: it shows Mosquito delivering a speech in the Senaat, one of the two chambers of the Federal Parliament of Belgium.

Partly because he is wearing a dark gray shirt and Malcolm X glasses, but mainly because of his charismatic voice and comportment, Mosquito evokes a long line of great Black orators from Frederick Douglass to James Baldwin, as he switches between booming and almost whispering. It’s as if different registers of speech—the serious and the comical, the authoritative and the offensive—have been chopped up and mixed into a salad of address. He offers casual salutations that range from the N-word to “Ladies and Gentlemen.” After discussing the temptation to cite John F. Kennedy, he does so. Performative self-contradiction is the foundation of his act.

It becomes clear that Mosquito is also tapping into a long line of great Black tricksters, from Anansi to Richard Pryor. His puns …

November 27, 2024 – Feature

On Katya Libkind

Kateryna Iakovlenko

“I would like to talk about my practice from the body of a dirty, envious dog that roars and emits secretions,” wrote the Ukrainian artist Katya Libkind in late 2023. Working in media as varied as set design, installation, and video, Libkind has described her work as “based on proceduralism, radical sincerity, and direct emotional experience.” With a focus on environment, community, and care, she explores ideas of beauty, doubt, and intuition in life and in dreams. In addition to working with atelienormalno, a workshop studio for artists with and without Down’s syndrome, she has taught art in a psychiatric hospital, and all of these experiences play into her multidisciplinary practice. Why did Libkind use the image of a dog when discussing her work?

Images of dogs in desperate straits have served as metaphor for the Ukrainian artistic community—conjuring a sense of confusion and the desire to cling to others to survive. I remember the abandoned street dog in photographs by Kharkiv artist Jury Rupin in the 1970s, personifying the aloofness, indifference, and loneliness of the Ukrainian intelligentsia during Soviet times. Two more recent iconic images: the dog who refused to cower on the ground after hearing explosions in Irpin …

November 26, 2024 – Review

Olivia Erlanger’s “Fan Fiction”

Caroline Elbaor

Four sculptures in the form of ceiling fans hang suspended in an otherwise empty gallery. These works—all dated 2024 and presented against the fluorescent lighting, bright-white walls, and cement flooring of a traditional white cube—are fully enmeshed in the architecture, resulting in an exhibition with all the hallmarks of aesthetic minimalism arranged for the sake of affect. The intended sense is of monotony. This is achieved by the simplistic setup and, more importantly, evokes the mundanity of domesticity that defines much of Erlanger’s practice across plays, films, installations, and sculptures.

Here, each sculpture is partially comprised of various home appliances—shower curtain rods, kitchen utensil holders, lamp cords, and wastepaper bins—that make up the ostensible fans, the blades of which are moulded into the shape of butterfly wings. These appliances reference her most recent short video, Appliance (2024), which debuted earlier this year in the American artist’s first extensive institutional solo exhibition in the US, at Contemporary Arts Museum Houston. It is also screening here, in the gallery’s adjacent viewing room. Consistent with Erlanger’s use of science fiction and horror in earlier works to explore the psychology underpinning the idea of home, she here depicts absurd situations—the arm of a contractor …

November 22, 2024 – Review

Emily Jacir and Michael Rakowitz’s “That thou canst not stir a flower Without troubling of a star”

Cathryn Drake

In the San Paolo quarter of Rome, artists Emily Jacir and Michael Rakowitz staged a “performative” dinner to commemorate the life of Palestinian poet and translator Wael Zuaiter, executed by Mossad agents at his home in the city fifty-two years earlier. Organized by curatorial collective Locales, it was the final event in a public program focusing on the body as an artistic medium for learning and transformation. Nearly one hundred guests gathered at long tables on the terrace of Città dell’Utopia, an international social laboratory dedicated to communitarian activism located in an eighteenth-century farmhouse that was a trattoria and antifascist hub founded by Augusto Volpi in 1907 and later a refuge for resistance fighters during World War II. Now an anachronistic apparition surrounded by apartment blocks, it is still a welcoming, convivial hive.

The poignant title, evoking the far-reaching repercussions of every action, is taken from a poem by Francis Thompson that Zuaiter quoted in an article published in L’Espresso shortly before his assassination. Zuaiter was the first victim of the Israeli operation Wrath of God, ostensibly targeting those held responsible for the massacre carried out by Black September at the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich. In 1980, several Israeli …

November 21, 2024 – Review

Bassem Saad’s “Century Bingo”

Lua Vollaard

This overview of the past five years of Bassem Saad’s “world-historical” practice engages with different forms of mourning the victims of “the American Century.” The term, coined by Henry R. Luce in 1941 and which the Marxist scholar David Harvey has argued “disguised the territoriality of empire in the conceptual fog of a ‘century’,” finds its antidote here: Saad’s latest exhibition is grounded in events, people, and sites, merging documentary history with acid aesthetics and revolutionary zeal.

Commissioned for this exhibition is the film Permanent Trespass, made together with Sanja Grozdanić and staged as a theater performance in a previous iteration. Here, it is installed on a large screen showing a fictional narrative and a small screen intermittently showing archival footage: pop stars from the referenced eras juxtaposed with burning Kuwaiti oil fields. The main film is set in a Belgian art nouveau mansion, its furnishings haphazardly wrapped away for an impending sale. Professional eulogists lead this clearance of colonial-era assets, the dense script delivered deadpan by the artists themselves. They reflect on their job alongside the work of eulogizing—but what they’re eulogizing (the human cost of the American Century?) remains unclear.

In doing so, they face off with institutional …

November 20, 2024 – Review

Glenn Ligon’s “All Over The Place”

Novuyo Moyo

Glenn Ligon’s takeover of the Fitzwilliam Museum is so “all over the place” that I had to come back for a second visit to see things I’d missed the first time around. It is relevant to his nuanced but pervasive intervention that the museum was founded in 1816 when Viscount Richard Fitzwilliam left his collection of art and cultural artifacts to the University of Cambridge with a bequest to construct a museum of art and antiquities. This leaves it with twinned affiliation: both to an esteemed educational institution and to a landowner whose fortune derived in part—as recent research by the museum has unearthed—from his grandfather’s investment in the transatlantic slave trade.

Ligon’s multimedia work often interrogates race, even if it cannot be reduced to that subject, and his subtle interventions into the museum’s collection are consistent with his multilayered practice. On the ground floor, Ligon has selected objects from the museum’s collection of porcelain from Europe and Japan, showing them alongside his take on Korean Moon jars, painted a blackish hue instead of the traditional white. On the floor above, Ligon has rehung flower paintings from the collection of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Dutch still lifes, rearranging them to form …

November 19, 2024 – Review

Tbilisi Architecture Biennial 2024, “Correct Mistakes”

Océane Ragoucy

Barely twenty-four hours after it was declared that Georgia’s parliamentary elections had been won by Georgian Dream—a party founded by a pro-Russian billionaire—the country’s president, Salome Zourabichvili, denounced a “total falsification” of the vote and called on her fellow citizens to protest. It feels apt, therefore, that artistic directors Tinatin Gurgenidze, Otar Nemsadze, and Gigi Shukakidze should have chosen the theme of “Correct Mistakes” for the fourth Tbilisi Architecture Biennial, with its multiple meanings, from useful errors to their possible rectification. This edition focuses on the seizure of natural resources, landscapes exploited for profit, forgotten ecological histories and—more generally, as the biennial’s statement puts it—the “disregard for climate change.” Their radical, resolutely provocative approach points to the urgent role and responsibility of architects, urban actors, and activists in preserving the commons.

The biennial unfolds as a vibrant, multifaceted structure: exhibitions, screenings, workshops, symposia, off-the-beaten-track site visits, and “toxic tours” of polluted and damaged places in different parts of the city. The selected projects thus provide multiple access points to the complex connections between climate, resources, their extraction and appropriation, starting from Georgia but not restricted to it. National borders are never directly invoked. Rather, it is a matter of the …

November 15, 2024 – Review

62nd New York Film Festival, “Currents”

Almudena Escobar López

Days before the New York Film Festival opened, dozens of filmmakers—many from the “Currents” section—published a petition urging the festival to cut ties with Bloomberg Philanthropies due to concerns over its implication “in facilitating settlement infrastructure in the West Bank and denying Palestinians their basic rights.” During the fortnight, anti-war demonstrators interrupted Q&As and screenings, and a parallel Counter Film Festival was organized. How do we approach film-making after a year of live-streamed genocide in Gaza? This question lingered over the “Currents” shorts programs, curated by Aily Nash and Tyler Wilson, which seek to foreground “new and innovative forms and voices.” A select group of films from the programs challenged how images influence our perception of reality, particularly in contexts of violence, prompting critical reflection on our roles as viewers.

Two films in “The Will to Change” program reveal the limits of observation, turning the horror of witnessing war into an act of self-reflection. Black Glass (2024) by Adam Piron conjures the ghosts of the past (and the present) by speaking about the intrinsic relationship between early image-making technologies and the ongoing processes of settler colonialism. Piron examines Eadweard Muybridge’s early photographic work, commissioned by the US Army to capture …

November 14, 2024 – Review

Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst’s “The Call”

George Kafka

Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst have in recent years been better known as spokespeople for the artistic possibilities of AI than as demonstrators of its uses. Numerous media profiles, their Interdependence podcast, and Dryhurst’s busy X account mean it has been easier to learn their opinions on AI than to engage with—and sometimes understand—the various tools, songs, images, and other experiments that the music/artist/research duo have produced.

Herndon and Dryhurst are both eloquent advocates for open-minded but certainly not uncritical engagements with AI for artistic practices and, by extension, its broader sociocultural impacts. They confidently tread the (admittedly very broad) ground between AI doomers, denialists, and Big Tech-boosters, with a particular focus on the ethical use of artists’ work to produce AI models—as seen in projects such as the website Have I been Trained?, which allows artists and photographers to find out if their work has been used to train AI models. And yet, approaching “The Call,” the duo’s first solo exhibition, at London’s Serpentine Gallery, I had little sense of what “art” awaited me and, I must admit, feared diagrams of neural networks were ahead.

Greeting visitors to Serpentine North is The Hearth (all works 2024), a wall-mounted instrument …

November 13, 2024 – Review

Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme’s “Until we became fire and fire us”

Oliver Basciano

The deep boom of a subwoofer meets you on the stairs to the small gallery. Inside, a two-channel video projected across opposite walls shows barren landscapes with figures moving through them, close-ups of plants and foliage, and more besides, the imagery by turns sped up, slowed down, color-adjusted, and layered. One half is framed to the dimensions of the space; the second is projected at an angle, so the pictures invade the ceiling and floor. It is a hypnotic, unnerving assemblage.

On the gallery floor, between the two projections of Until we became fire and fire us (2023–ongoing), stand metal barricades, like sections of a security border, on which printed frames from the film are attached. Above, sheer fabric banners hang, printed from further images culled from the video. To one side, copies of a newspaper—the New York War Crimes, mimicking the design of the New York Times—are piled up on a pair of bricks and available for the visitor to take away. It tells a century-old story of Palestinian struggle and Israeli aggression through a succession of commissioned texts.

The materiality of all this stuff is in stark contrast to the subject of the thirty-two-minute, mixed-media work that lends …

November 11, 2024 – Review

Ariella Aïsha Azoulay”s “Unshowable Photographs”

Jeremy Millar

In 2009, the curator, filmmaker, and writer on visual culture Ariella Aïsha Azoulay visited the archive of the International Committee of the Red Cross (CICR) in Geneva to look at photographs taken in Palestine during the years 1947–50. Azoulay had already worked extensively in the Israeli state archives, creating from these another archive which she called Constituent Violence 1947–1950 (first published in book form in 2009), and hoped that the photographs held by the CICR would be somewhat different from those she had, in her words, “been able to view in Zionist archives.”

These are the years of the establishing of the state of Israel, of course, and of the Nakba, or “catastrophe,” the violent displacement of approximately half the Arab population in Palestine—around 750,000 people. While the CICR had been present “at places in Palestine where massacre, expulsion, and destruction had taken place,” they had relatively few photographs, and most of these were not taken during the Nakba. Indeed, many of them were similar, though not identical, to those seen by Azoulay in Israeli archives—the same people, the same place, the same ongoing event, but just shown from a slightly different angle, a slightly different point of view.

But …

November 8, 2024 – Book Review

Hervé Guibert’s Suzanne and Louise

John Douglas Millar

There is a line of criticism that argues that Karl Marx’s Das Kapital (1867–94) is the great gothic novel of the nineteenth century. It’s a line that runs through an essay by the poet Keston Sutherland that, in a bravura piece of close reading, explores the stakes involved in the translation into English of the German word Gallerte. When Marx writes about “bloße Gallerte unterschiedsloser menschlicher Arbeit,” Sutherland argues, he does not refer only to “congealed quantities of human labor,” as the line is most often rendered in English.

He is in fact referring to a staple of German foods and cosmetics; gallerte, Sutherland explains, “was made from the off-cuts and the discarded bits of animals from early industrial slaughter processes. It was the stuff the bourgeoisie wouldn’t want to eat in its natural form, but which could be boiled down and turned into this great mush and then used in breakfast condiments or cosmetics.”

Marx wants the reader to feel the full brutality of what capitalism does to laboring bodies. He wants to reveal the horror beneath the social codes by which the bourgeois protect themselves from the gory facts of the capitalist mode of production sustaining their existence. …

November 7, 2024 – Review

“Meditation Room: Sacred Spaces Program”

Natasha Marie Llorens

The tiled floor of Konsthall C has seen hard use, both in the twenty years it has functioned as an experimental art space and, before that, as the common laundry room for the rental apartments in this suburb of Stockholm. Time and traffic have eroded the diagonal pattern of beige and dark-gray squares, and now the floor looks clean and utilitarian. This kind of straightforward durability is the appropriately mundane ground for the inaugural exhibition of Mariam Elnozahy’s first program as Konsthall C’s artistic director. Her two-year thematic proposition “Sacred Spaces” is balanced between a positivist understanding of the sacred as someplace metaphysically safe and an idea that the contemporary art institution might offer “a place to discuss religious pluralism.” The intervention arises in a febrile context: a long-running debate in Swedish courts over whether burning the Koran could be seen as a form of political protest; an extreme rise in gang-related gun violence—Sweden is now second only to Albania in Europe—with attendant media coverage often emphasizing immigration and ethnic identity, with overtones of politico-religious affiliation.

It would have been easy to open a program along these thematic lines with something confrontational, but instead Elnozahy reproduced, inside the gallery, the …

November 5, 2024 – Editorial

Stages

The Editors

Sometimes it is better to let the work speak to the moment. We begin this month with a text reflecting on a recreation of the “meditation room” installed at the UN headquarters by a diplomat later rumored to have been murdered for his commitment to the organization’s ideals. While we must acknowledge that even spaces of spiritual experience are implicated in structures of power, writes Natasha Marie Llorens, this work suggests that “the most violent stages” can nonetheless “be instrumentalized in service to subtle and multivalent forms of resistance.” We can only hope.

It is the nature of art that the work (and its criticism) will always be inflected by those events by which it—and we—are surrounded. That is especially the case when those events are as consuming of our attention as the US election or Israel’s increasingly unconstrained destruction of Gaza. An exhibition of Ariella Aïsha Azoulay’s “Unshowable Photographs” also illustrates how works of art can slip the purposes to which they are put by transforming photographs whose meanings have literally been fixed into drawings that might speak for themselves. That there are no illusions here about the function of images is not a cause for despair so much …

November 4, 2024 – Review

“Made in Germany? Art and Identity in a Global Nation”

Luise Mörke

On the Harvard campus, relics of Germanic high culture are never far away: a bronze replica of a medieval lion sculpture from Lower Saxony graces the courtyard of Adolphus Busch Hall, named for an émigré who made his fortune selling—what else?—beer and diesel engines. A counterpoint to that building’s historicist opulence can be found in the sober Modernism of the Law School’s graduate dorms designed by a team led by Walter Gropius during his tenure at the university. As ciphers for rigor, perfection, and intellectual prowess, mythical versions of Germany are deployed as fodder for the Harvard myth itself.

“Made in Germany? Art and Identity in a Global Nation,” at the university’s Busch-Reisinger Museum, adds a further chapter to this transatlantic double vision, focusing on art since 1980 from the GDR and the Federal Republic (FRG). However, national myth-making here gives way to an astute selection of artworks that pry open the cracks in a state that defines belonging foremost through adherence to cultural and linguistic standards, evident in the language and knowledge test that immigrants must pass for naturalization. “Made in Germany?” coaxes out the tense dialectics between a nation’s openness towards outside cultures and economies, and the nationalist …

October 30, 2024 – Review

Kim Lim’s “The Space Between. A Retrospective”

Adeline Chia

Kim Lim’s dark wood sculpture Pegasus (1962) is an earthbound, stiff-backed version of the mythical flying horse. Shaped like a totem, it has no discernible head or legs, only a central column to which two slim semi-circular pieces of wood (the “wings”) are hinged. Pegasus, steed of the muses and symbol of the unbridled imagination, is portrayed here with a certain restraint. In fact, the sculpture reminds me of a practitioner of another disciplined art—a straight-backed ballerina moving between first and second positions, arms opening and closing gracefully.

Subtlety and economy define Kim Lim’s practice, which includes abstract wooden and stone-carved sculptures, often inspired by nature, as well as prints that were developed in tandem. Only in the past two decades has Lim received attention in her two home contexts: Singapore, where she was born in 1936, and England, where she attended art school, started a family, and lived until her death from cancer at the age of sixty-one. Major shows at Tate Britain and Hepworth Wakefield have situated her in British postwar art history alongside Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, and Lim’s husband William Turnbull. The Singapore Tyler Print Institute staged a retrospective of her prints in 2018, establishing her …

October 28, 2024 – Review

Diego Marcon’s “La Gola”

Michael Kurtz

Diego Marcon’s short films pair idiosyncratic approaches to animation with painful and provocative subject matter. In Monelle (2017) sleeping girls are tormented by ghoulish CGI figures amid the darkness of the old Fascist headquarters in Como. In The Parents’ Room (2021), a father, played by an actor wearing an emotionless mask, performs an opera about how he murdered his family. And in Fritz (2024) a computer-animated boy hangs from a noose, half-dead but still yodelling.

His new film, La Gola (2024), dramatizes an epistolary exchange between Gianni and Rossana, who are represented by hyper-realistic mannequins. The two characters appear in a series of close-ups, every time in a new outfit and location, as their letters are read in a voiceover backed by organ music. Gianni recounts the details of a recent feast, from a medieval soup served in an eggshell to Torta Fedora, a Sicilian cake covered in “mischievous ruffles” of “whipped ricotta,” which he calls “the bakeable Baroque!” Meanwhile, Rossana sends updates on her mother’s declining health, reporting an assortment of gruesome ailments including “flaccid little blisters” that ooze “syrupy fluid” and “diarrhoea accompanied by mucus.”

In this caricature of traditional gender dynamics, he indulges in unchecked consumption while …

October 25, 2024 – Feature

Warsaw Roundup

Ewa Borysiewicz

Eight years of government by the right-wing Law and Justice party, which came to an end a year ago, severely damaged Poland’s cultural sector, not least by undermining the credibility of the capital’s art institutions. In these circumstances, the responsibility of safekeeping Warsaw’s reputation as a regional hub for contemporary art fell to its commercial galleries. In spite—or perhaps because of—the political and economic climate, recent years have also seen a growing number of non-commercial and artist-led initiatives in Warsaw, gathered together by the annual FRINGE Warszawa. Coordinated by members of the independent art community, its third edition platformed more than eighty spaces, complementing the more than 100 openings taking place as part of the simultaneous gallery weekend.

In contrast to the gallery weekend, the venues of which are concentrated around the city center, FRINGE sprawled across Warsaw. Visitors were invited to scout the Vistula riverbank for Karolina Majewska’s “Holy Trees” (2021–ongoing), a series of beeswax body parts attached to tree trunks, and venture to the Kowalscy confectionery, where Kacper Tomaszewski and Mateusz Włodarek’s exhibition “Through the Stomach to the Heart” celebrated friendship and sweets. The curators playfully paired the works with offerings from the city’s traditional pastry shop, giving …

October 24, 2024 – Review

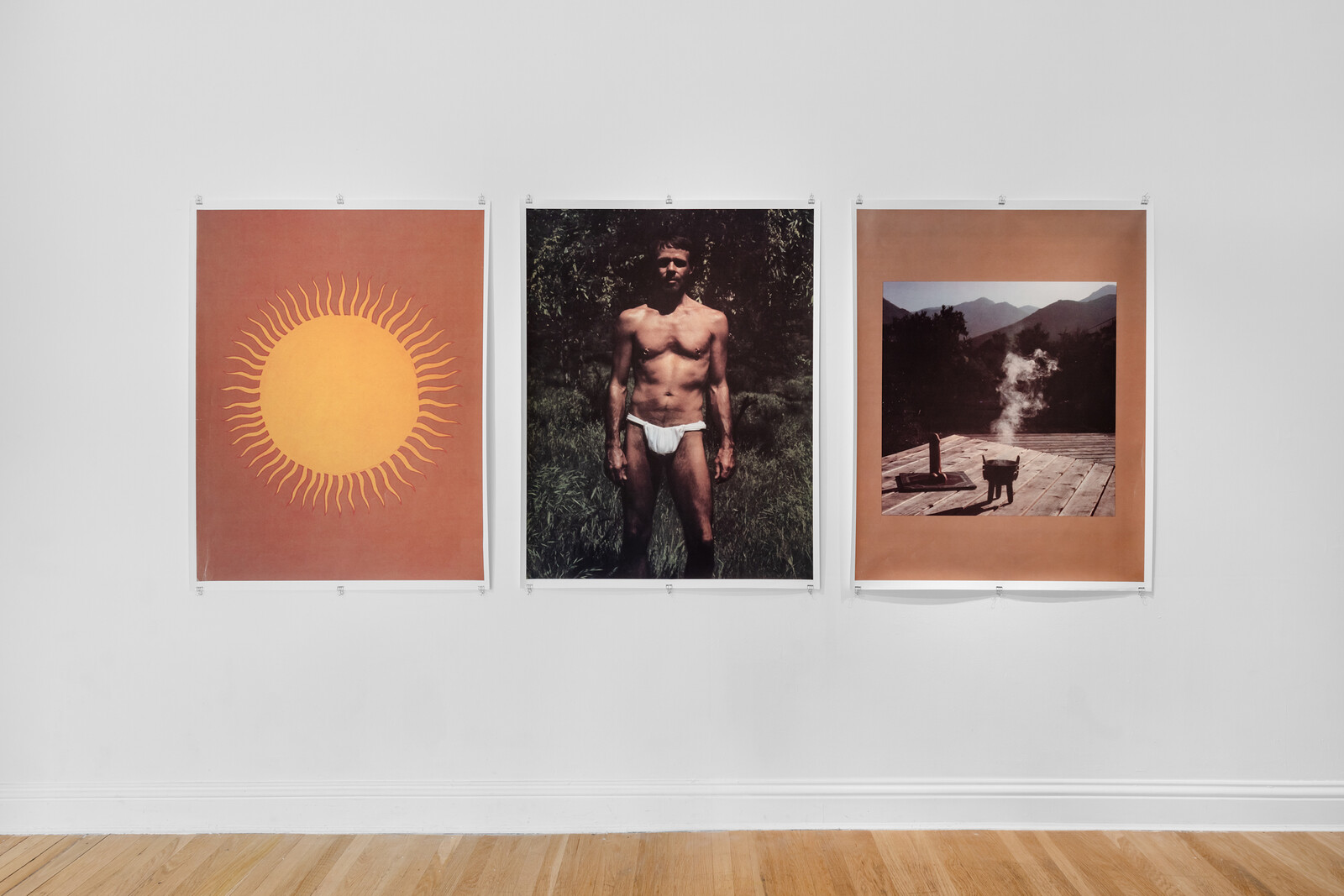

Sam Ashby’s “Sanctuary”

Dylan Huw

Sam Ashby’s film Sanctuary (2024), which forms the centerpiece of this solo exhibition, examines the architectural and psychic remains—and perhaps under-explored potential—of a queer spiritual community founded, in the seventies, by onetime film director Christopher Larkin. When Larkin’s 1974 directorial debut, the gay romantic drama A Very Natural Thing, met a lukewarm critical and audience reception, he reacted in the way gay men throughout history have confronted such disappointments: by packing his bags and fashioning himself a new identity. Larkin lived nomadically for much of the remaining decade, sustained by family money and the liberating atmospheres of Fire Island and San Diego, before re-emerging as the sexual guru Peter Christopher Purusha Androgyne Larkin.

The pursuit of all-consuming spiritual ecstasy by means of fisting, and other anally focused activities, formed the basis of his teachings. These were inflected equally by New Age pop psychology and, more improbably (or not), by his experiences as a young Catholic monk. The prophet set forth his doctrine in his book The Divine Androgyne According to Purusha (1981), a remarkable document of then-nascent fetish culture which documents his quest for “cosmic erotic ecstasy in an Androgyne bodyconscious,” seeking extreme sexual pleasure as a method of obliterating …

October 22, 2024 – Review

Art Labor’s “Cloud Chamber”

Stephanie Bailey

Referring to the cà phê võng providing rest and refreshment to drivers on Vietnam’s provincial highways, this first institutional survey of Art Labor’s activities, curated by Celia Ho, opens with an invitation: to sit (or lie) on a hammock and drink Vietnamese coffee brewed from robusta beans grown in the country’s Central Highlands. The staging of this vernacular rest-stop performs a spatial reconfiguration. No longer are we in Hong Kong, but somewhere in Tây Nguyên, located within the Southeast Asian Massif known as Zomia, its complex textures expressed by a chorus of sculptures, installations, and instruments created by Art Labor—founded in 2012 by artists Thao Nguyen Phan, Truong Cong Tung, and Arlette Quynh-Anh Tran—and collaborators from the Indigenous Jarai community, with whom Art Labor have been working since 2016, alongside invited artists. Among them is musician and artist R Cham Tih, whose standing bamboo instruments in the gallery embody the recuperation of lost Jarai musical traditions through restorative innovation. While K’loong Put (2024) is a traditional xylophone, albeit with additional notes, Klek Klok (2024) is a new design drawing on traditional bamboo gongs used to deter wild birds from the fields.

A dialectics of loss and recovery infuses this exhibition, …

October 18, 2024 – Feature

London Roundup

Chris Fite-Wassilak

A BlackBerry phone in a vitrine plays a short video: a nighttime shot of a building on fire. The scene is familiar to anyone who was in London during the 2011 unrest that grew out of the police shooting of Mark Duggan: the House of Reeves furniture store in flames, caught on both shaky handheld phone and swooping helicopter footage, broadcast and shared over and over. In the next room in Imran Perretta’s “A Riot in Three Acts” at Somerset House is a meager set, as if belonging to an abandoned play, with a few benches plonked amongst pebbles strewn with rubbish, a large backdrop painted with a nondescript shopfront.

This is Reeves Corner in Croydon, where the burnt-out building once stood. A soundtrack of swelling strings fills the room—a quick-paced march, followed in a later section by soaring high notes—and adds narrative tension and the hope of redemption to Perretta’s non-film. Melodrama is part of the point here: while listening, I’m creating a mental film loaded with scenes shaped by that news footage, and bumped up with film conventions. History repeats itself, Perretta’s restaging suggests, first time as tragedy, second time as Hollywood special.

The causes of the 2011 …

October 17, 2024 – Review

Gregg Bordowitz’s “Dort: ein Gefühl”

Kirsty Bell

Gregg Bordowitz has been writing, publishing, performing, and teaching consistently and prolifically since the early nineties in New York, making “agitprop” videos as an AIDS activist and member of ACT UP. Though his material output is slim, his wordcount is substantial. Rather than focus on the early activist works for which he is best known, this exhibition concentrates on writing as the core of his artistic practice, but also as a daily habit—“writing as an activity of thought,” as Kunstverein Director Fatima Hellberg puts it—that becomes material testament to his ongoing presence, as a long-time survivor of HIV.

To create an exhibition from this ephemeral practice is audacious, particularly in the Kunstverein’s cavernous former flower market hall, but Hellberg has a track record of conjuring shows from unruly or nebulous bodies of work (David Medalla’s 2021 retrospective, for example, or the large-scale solo exhibition of Georgian artist Tolia Astakhishvili in 2023). In the absence of discrete objects, the exhibition relies on subtle gestures, the first of which is a narrow red line affixed to the wall, three inches from the floor, that follows the entire perimeter of the exhibition space. It establishes intention and constructs a kind of “holding environment,” …

October 15, 2024 – Review

Jenna Bliss’s “Basic Cable”

Chris Murtha

The idea of “Wall Street,” a metonym for global capitalism measured against whatever remains of “Main Street,” has far outgrown its connection to the New York thoroughfare that traces the path of the city’s seventeenth-century border wall. Today, the home of the New York Stock Exchange is heavily secured by bollards, fences, and barricades that regulate and restrict public access. Armed with her camera, native-New Yorker Jenna Bliss roams the narrow canyons of Lower Manhattan. Her unsteady lens lingers on passersby and commercial storefronts; gazes skyward to scale gleaming towers; and hovers, from afar, on the skyline’s iconic, yet ever-morphing silhouette. With the September 11 attacks, the 2008 financial crisis, and the Covid-19 pandemic as inflection points, Bliss blends fact with fiction, past and present, to probe our collective perception of Wall Street as a place and an idea—from the ground up.

To produce the Super 8 films and photographic lightboxes on view at Amant, Bliss splices and recombines her material so that her subjects are neither fully revealed nor entirely obscured, but rather held in disorienting tension. Conspiracy and Spectacle (both 2021 and under two minutes long) loop continuously on box monitors mounted atop tall pedestals arranged to mimic …

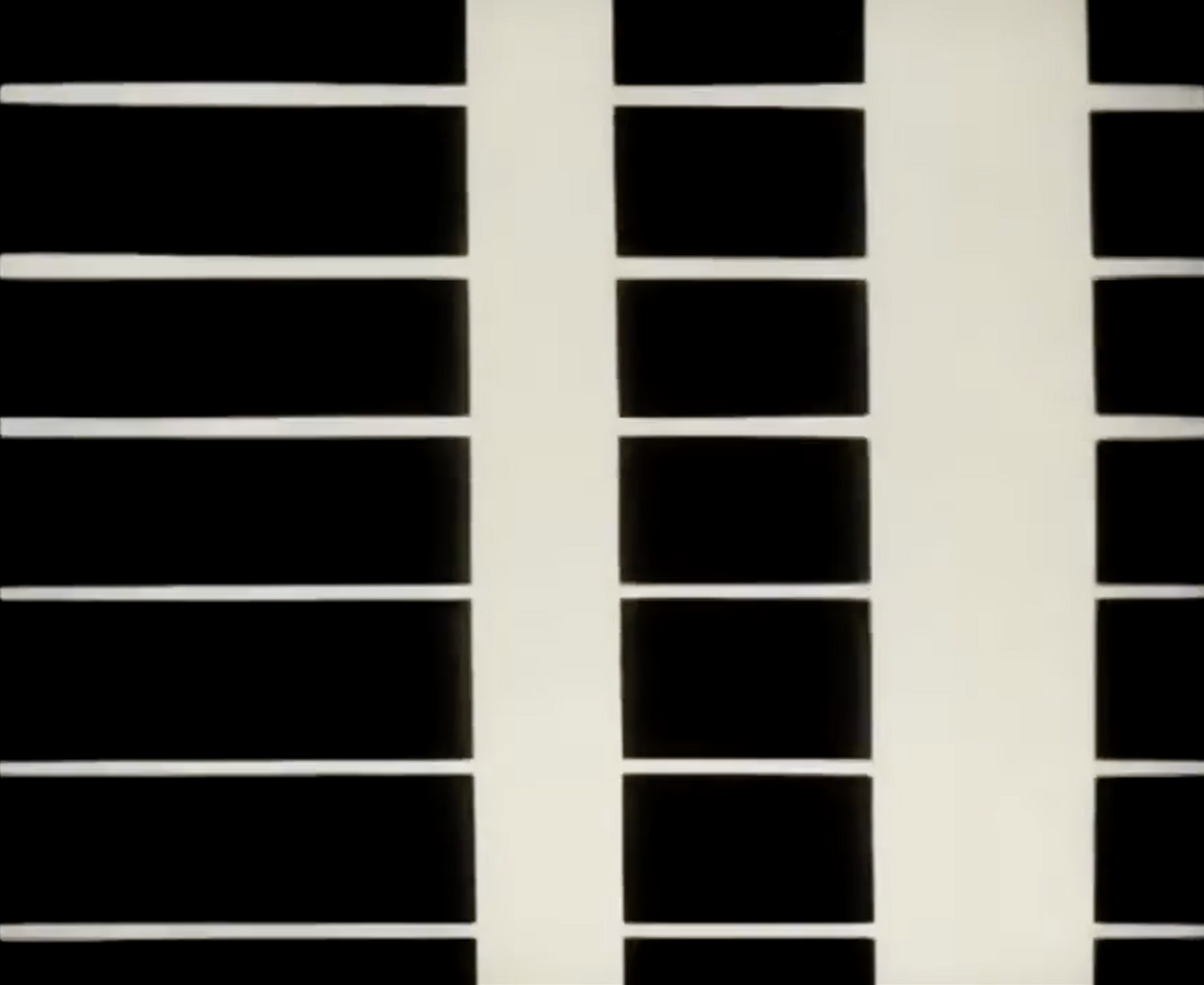

October 11, 2024 – Feature

Jo Baer

Rachael Rakes

Jo Baer nicknamed the five large-scale abstract paintings that compose “The Risen” (1960/61–2019) series her “zombie” works. Despite living in Amsterdam for the past forty years, Baer remains associated with the American minimalist movement, both for her works and for her bold public engagements (and squabbles) with the New York art world’s sculptors, critics, and dealers. Destroyed by the artist in the early 1960s, before which they were documented by Polaroid photographs, the “Risen” paintings were recreated in 2020.

[figure ROSE_JOBAER6]

A few years earlier, the term “zombie formalism” was omnipresent in Western art criticism. A condemnation coined by Walter Robinson, it referred to an abstraction that had come back into favor in casual collusion with the speculative market, and suggested that an aesthetic not formed by new ideas but by a final evacuation of whatever shred of meaning was allowed to live within abstract painting. This notion came and went quickly in the currency of hot takes, but it hints at the changes and some lingering positional uniformity in art criticism in the six decades between Baer’s conception and recreation of these works.

Neither era’s discourses have sufficiently contended with Baer’s minimalist project, which found its stride and distinctive …

October 9, 2024 – Book Review

Carrie Rickey’s A Complicated Passion: The Life and Work of Agnès Varda

Brian Dillon

I once met her, if you could call it that, for a few seconds at the Frieze Art Fair; she turned to the person who introduced us and asked: “Is he going to look after me?” She must have meant it ironically, because in 2009, a decade before she died, Agnès Varda was not only busier than ever—after photography and film, she had lately embarked on her “third career” as an installation artist—but honored as a New Wave instigator and a pioneer feminist director. Also, to her delight, more and more beloved as an eccentrically turned-out presence on the film-festival and art-fair circuits: beneath the lifelong bob and variegated dye-job, she might turn up in silk pajamas, purple tracksuit (both by Gucci), or dressed as a potato. Varda’s last years formed a giddy and heartening coda to a life and a body of work that were playful and profound. And an artist who, if Carrie Rickey’s new biography of her is to be trusted, was utterly tireless on every front, artistic or intimate.

Varda was born in Brussels in May 1928—her parents named her Arlette, because she had been conceived in Arles. When the Nazis invaded Belgium in 1940, the …

October 8, 2024 – Review

Gustav Metzger’s “And Then Came the Environment”

Rob Goyanes

Gustav Metzger hated cars. Not only for the pollution and noise, but because of their association with the hermetically sealed “gas vans” that Nazis used as mobile extermination chambers, diverting exhaust fumes into the vehicles’ interiors. Conceived but not realized for the United Nation’s first world conference on the environment in 1972, Metzger’s installation Project Stockholm, June (Phase 1)—finally executed for the Sharjah Biennial in 2007—included 120 cars, parked around a clear rectangular structure, their motors running constantly and filling the space with gas. The resonances with the United Arab Emirates (one of the world’s largest oil economies), and Los Angeles itself, site of this exhibition, are clear.