In 2023, Refik Anadol launched the digital artwork collection “Winds of Yawanawa.” In collaboration with the Yawanawa people of Brazil, Anadol collects data from the Brazilian rainforest and combines it with drawings by Yawanawa artists to create 1,000 AI-generated NFTs that can be purchased with Ethereum. This massive undertaking is intended to “protect the Amazonian rainforest” by “preserving and uplifting Indigenous modes and models of environmental protection and sustainability.”1 Anadol, who’s made a name for himself championing the use of artificial intelligence as a new “pigment,” has largely organized his practice around environmental crusades. In 2024, his AI-generated portrayal of coral reefs Large Nature Model: Coral—a work which, according to an official United Nations press release, “offers an unprecedented glimpse into the vastness and complexity of our oceans”—debuted at the UN as part of a sustainability initiative. In addition to centering the Yawanawa through data collection and transforming coral reefs into two-dimensional, undulating masses of color, Anadol is broadly engaged in using AI to represent our natural environment in a bid to reimagine and save not just coral reefs or tropical rainforests, but “the future.” What is going on?

“Hegemony,” wrote Raymond Williams, “is the continual making and remaking of an effective dominant culture.”2 The concept of hegemony was used by Williams as a way to rescue culture from a reductive and one-way formulation of base and superstructure, where the base—Fordist manufacturing for example—is the cause of the superstructure or all things “merely cultural.” Rather, hegemony places literature, paintings, films, dance, television, music, and so on at the center of how a dominant culture rules or how a ruling class dominates. This is not to assert that art is propaganda for capitalism (although sometimes it is). Nor is it to revert to theories of “art for art’s sake” and the normative metaphysics of liberal cultural criticism (Art’s social value is its independence from politics. What about “beauty”? etc.). According to Williams’s theory of hegemony, art is one way of enlisting our desire in the "making and remaking" our own domination. But desire is unstable and, as an important part of maintaining a dominant culture, art is also, potentially, a means of its unmaking.

Hegemony, it should be noted, is not non-violent. It is always backed up by force, but it allows power to maintain itself without constant recourse to the police or justice system. Within the boundaries of an imperial power at least, hegemony allows ruling classes to govern with the enthusiastic consent and participation of subjects who assume that, for all of its problems, this social order is worth preserving in some form. Hegemony is most effective when it is experienced as sentiment (this movie is “fun to watch,” that immersive experience is “cool”) and understood as common sense (technology is not the problem, it is just used badly by capitalists).

View of Refik Anadol's Large Nature Model: Coral at the United Nations Headquarters, New York, September 21, 2024. © UN Photo. Photo by Loey Felipe.

Since at least the nineteenth century, art has been one of the primary ways a secular culture has translated economic and political domination into pleasure and demonstrated the superiority of capitalist economies. It is one of the ever-evolving ways that we are enlisted in the reproduction of a society that many of us recognize as terrible. It is why we hesitate to actually “shut it down” as the popular protest chant goes. The list of atrocities is long, but for many of us, the list of small pleasures is longer.

Writing about the realist novel, Franco Moretti argued that “it is not enough that the social order is ‘legal’; it must also appear symbolically legitimate … It is also necessary that … as a convinced citizen, one perceives the social norms as one’s own.”3 The cultural field of the twenty-first century is vast and chaotic, but the formalized, institutionally legitimated visual objects produced using AI are not a bad candidate for the representative cultural form of recent decades. In the nineteenth century, the realist novels of men like Honoré de Balzac, Emile Zola, or Theodore Dreiser helped industrial capitalism appear as a cohesive social reality—the normal state against which threats and disruptions were to be measured—rather than the ongoing, often incoherent violence of enclosure, exploitation, and incarceration that it was. Through descriptions of recognizable material circumstances and claims of objectivity and scientific accuracy, these novels aestheticized social life, and the result was a functioning whole within which lives were lived, uninterrupted, if imperfectly, from beginning to end; where moral agents made conscious decisions and were the victims of unjust but always legible social forces or political intrigue. Importantly, the pleasure of reading these novels was a pleasure in consuming everyday life, “real” life. Eventually, the pleasure of recognizing reality in this representative economy of language and narrative structure becomes a habit of measuring reality against it.

It is not a coincidence that MoMA installed Anadol’s Unsupervised (2022) in the lobby at a moment when the economic and political operations of Silicon Valley were becoming increasingly central to the organization of our personal, economic, and social existence. Not least because it is obvious to so many that the politics of Elon Musk and Peter Thiel are anathema to the wellbeing of the population at large. It has been clear for some time that the dominant culture of liberalism or neoliberalism is no longer effective. A new order is in the process of making itself, and we are learning to enjoy and understand it through chimerical images, colorful, immersive art installations, and free copy-editing software. Meanwhile, very real actors are shoring up very real power to enclose and extract vast amounts of information and mineral resources and order social and economic life in the interests of twenty-first-century robber barons.

Kate Crawford (@katecrawford) X post, September 20, 2019, https://x.com/katecrawford/status/1175128978274816000?s=46.

Like the realist novel, the artwork produced with technologies that fall under the umbrella of machine learning varies in scope, quality, popularity, political investment, and content more broadly. While many major museums seem set on acquiring crowd-pleasing, generative artwork barely distinguishable from non-intelligent computer animations of decades past, not everyone in this field uses unconscionable amounts of electricity to produce vapid seascapes set to smooth jazz. Trevor Paglen and researcher Kate Crawford have used these technologies against themselves to explain “the racist, misogynistic, cruel, and simply absurd categorizations embedded within ImageNet,” one of the most widely used training sets for machine learning.4 ImageNet Roulette (2019) reveals the regressive taxonomy being reproduced by this allegedly advanced technology by inviting people to upload selfies and see what category of person they are according to an AI trained on this data. Due to this publicity, ImageNet’s person dataset is no longer available, although, as they point out in “Excavating AI” this does not mean it is not in use. The content of the dataset might be missing, but its logic has already been reproduced uncountable times.

Another collaborative approach to AI is musician-artists Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst’s technically virtuosic and sometimes esoteric experiments exploring the capacity of AI neural networks to reconfigure and challenge received notions of subjectivity and authorship. Holly+, an AI trained on Herndon’s voice, will “cover” songs and other sounds using a composite of Holly’s voice, suggesting that a dispersed, non-agency is part of artistic subjectivity and offering a convincing argument for the artist as a cyborg. These projects, importantly, aren’t being made simply for their own sake. While less journalistic than ImageNet Roulette, Herndon and Dryhust’s work is still concerned with demystifying machine learning. Spawn, one of Dryhurst and Herndon’s early AI endeavors, has been trained on data gathered through public performance and audience participation in carefully documented “ceremonies.” In building Spawn, Herndon asserts that they “were trying to communicate that it’s not just some kind of alien intelligence ... It’s all of this human activity.”5 The music produced using these new instruments makes it clear that they are instruments, even as Herndon’s repeated referral to Holly+ as “she” or “her” muddies the waters.

Artists like Anadol are useful because, to borrow a phrase from Karl Marx, they can’t help but blurt out the stupid contradictions of the late capitalist brain. But more sophisticated and creative uses of this technology are also troubling. How machine-learning technology is used matters, but the fact that it is being used, full stop, merits equal attention. As Herndon and Dryhurst point out and as Crawford and Paglen show, AI training sets differ from sampling or collage because they don’t reproduce the content of the training set; they reproduce the logic of the training set. The concealment of this logic—the forgetting or disappearance of the training dataset—is a structural component of generative AI. It is forgetting, not memory, that allows it to appear intelligent. Attending to the logic of particular datasets is important—we live with them and their consequences. But the logic of the AI neural network itself is not a politically neutral form ready to be redeemed by morally upright data. If we attend to the logic of generative AI at the most general level—dataset created, dataset forgotten—we see that it is the instantiation, the concrete product, of a social order explicitly organized around mystification. Given that machine learning is dependent on a structure of willed amnesia, it is fair to ask how many pleasurable versions of the problem are we going to produce before the ouroboros just strangles us.

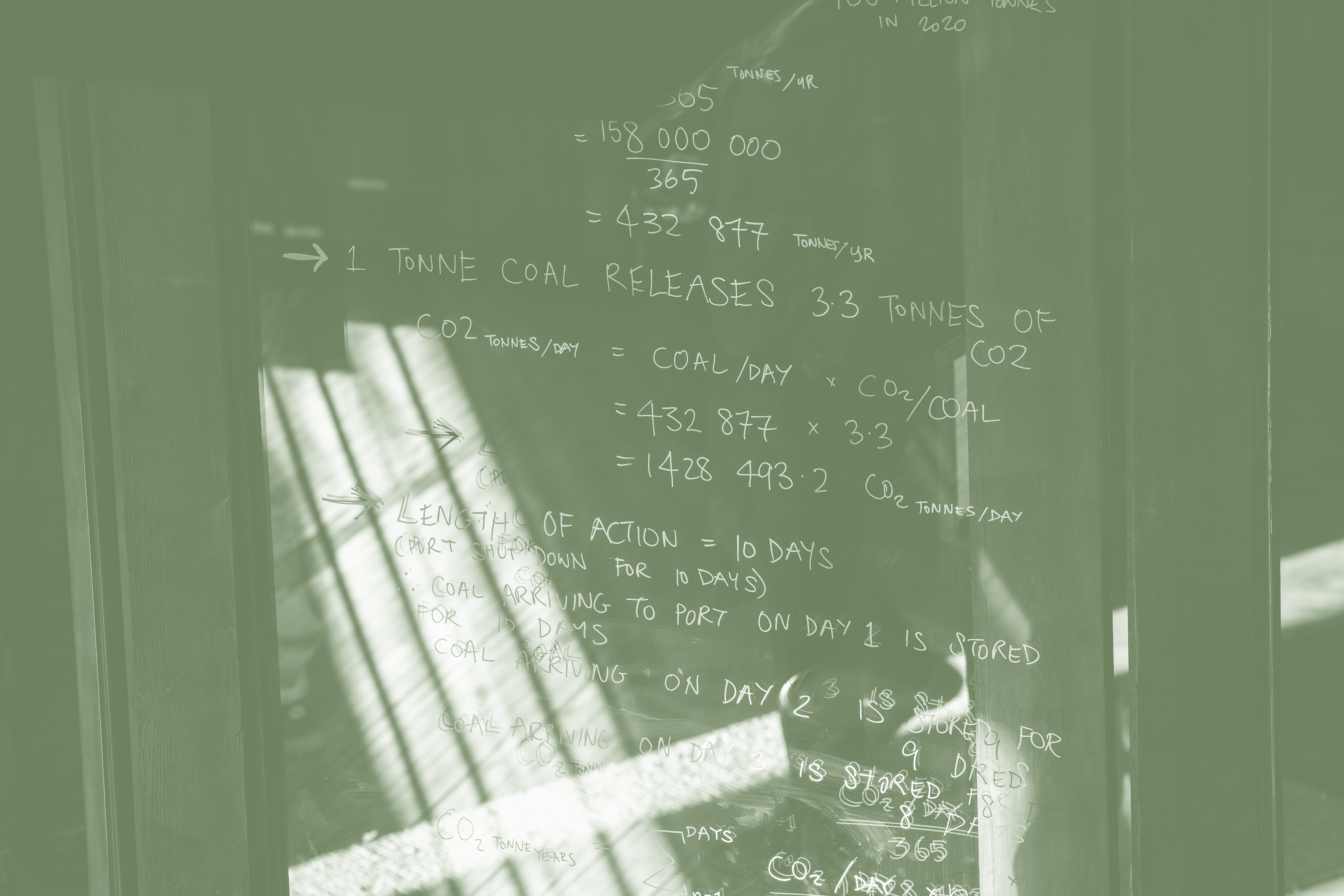

There are basic, utilitarian reasons to take a principled position against the excesses of images produced by generative AI that do not apply to other forms of media: these projects are capital-intensive and environmentally devastating. AI-powered internet searches use around 100 times that of a good old-fashioned Google search. The carbon footprint left by training, retraining, and then using AI models is enormous. Just training Chat GPT-3 produces a carbon footprint equivalent to driving 112 gasoline-powered cars for a year.6

Given the potential material impact of these projects, Anadol’s repeated promises to produce some future benefit are stupendous evasions of responsibility to the present. This is typical of a techno-political mindset: today there may be problems, but tomorrow the benefits will far outweigh any immediate costs. Upon inspection, these promises are so miserly they aren’t even worth keeping. “Large Nature Model: Coral” might be a first step toward 3D-printed coral; AI helps us imagine a future where carbon neutrality might be a possibility; AI raises awareness about the future of glaciers through art’s unique ability to communicate.7 When asked about the obvious contradiction involved in using a technology that is estimated to produce a carbon footprint equivalent to the entire aviation industry, Anadol coolly remarks that he is proud to be using “renewable” technology.8 His critics, he contends, are “lazy, not well-researched people” who “cannot understand what AI means.”9

A project that both requires and promotes this sort of energy usage claiming to save coral reefs, glaciers, and the rainforest just doesn’t make any sense, but eventually it will. Common sense is not found, it is made. The now constant crisis of climate change makes the contradictions of capitalism far more difficult to ignore, and Silicon Valley’s organic intellectuals are left with the task of resolving these contradictions for a disturbed and increasingly suspicious public. Anadol has not done a very good job of this, but in his failure, he has made some of these contradictions extremely clear.

Google Data Center - The Dalles, Oregon, May 17, 2015. Photo by Tony Webster. Creative Commons 2.0.

The claim made by Anadol and machine learning at large is that the solution to our greatest material crises is information-gathering and knowledge-creation. The soporific consistency of the images produced by Anadol’s algorithms is a conveniently perfect illustration of how little we learn from these superhuman brains. There are always exceptions, but what we generally get from all of this information is aesthetically consistent and conceptually thin. The related idea that technological progress and all of the knowledge that it produces and visualizes for us is the solution to climate catastrophe is more sinister. The coral reefs, disappearing rainforests, and Indigenous communities that Anadol claims to save are the most immediate victims of the anthropocentric climate change being accelerated by the energy needs of his sophisticated “pigments.” The so-called knowledge production that accompanies these operations is not incidental but central to a totalitarian project.

By converting unreproducible customs, organisms, individuals, texts, and artworks into absolutely fungible images, other ways of imagining the future are made to disappear. In their place is the future that Anadol has promised to save: a substitute complexity in the form of a dataset that most people couldn’t possibly understand, let alone alter, and whose effect is a monstrous cultural leveling. All of this, we are told, will reveal something new and crucial and world-saving that could not be known in any other way. As ever more powerful computers crank out new and better climate models, we will finally know the future, and by knowing the future, we will save it. But what future can be imagined, let alone realized, with technology that transforms pristine lagoons into toxic heaps of electronics and demonstrably contributes to rising global temperature and its many and varied unnatural disasters?

Williams argued that “it is a fact about the modes of domination that they select from and consequently exclude the full range of actual and possible human practice.”10 As datasets continue to increase quantitatively, their fascist exclusions are concealed by the extent of their extraction, but they are no more universal than the universalism of, say, the European Enlightenment. The repetitive, homogenous output of image generators and their non-relation to distinct inputs, even the uneasy intuition that you’ve seen it somewhere already, demonstrates the extent of this exclusion. In a structure that mimics the extractive devastation required to power these screen dreams, the more data it collects the more thoroughly decimated the informational landscape becomes. Rather than the adage “garbage in, garbage out,” favored by computer scientists and statisticians, AI’s transformation of inputs into visual objects is a matter of “value in, garbage out.” Art collection in, garbage out; literature in, garbage out; apples in, garbage out; human subject in, garbage out; Indigenous lifeways in, garbage out.

We are aware of the capacity of capitalism to co-opt oppositional cultural practices. However, not everything is equally visible to the dominant gaze. Because “the internal structures” of hegemony—such as artistic production and institutional promotion—“have continually to be renewed, recreated, and defended,” writes Williams, “they can be continually challenged and in certain respects modified.”11 The dominant culture will always overlook certain “sources of actual human practice,” and this leaves us with what Williams calls residual and emergent practices. Practices that have escaped, momentarily, or been forgotten by this oppressive selection process; fugitive practices that offer some extant, counterhegemonic possibilities. This is precisely why the “democratic” tendency of ever-expanding datasets is disturbing rather than comforting. It is also why a defense against the oppressive expansion of generative AI needs to be sought outside of a neural network in actual social relationships.

In an almost satirical performance of moderate liberal ideology, the New York Times has suggested that because “its training data … [represents] every conceivable view” AI in general is “a moderate by design … usually, you’ll get an evenhanded summary of what each side believes.”12 Or, as Anadol’s oeuvre demonstrates, you will get slight variations of the same image. This is not “every conceivable view” but a single, repeated perspective that has reduced the richness of its sources to an endless recombination of visual effects that exhibit differences in only the most technical sense. This isn’t just a thin equality, but a definition of equality as colonial expansion. This isn’t a metaphor: the material resources needed to run these machines require violent imperialism and all of its diplomatic doppelgängers. To materially produce the common sense of the New York Times, whole ecosystems must be destroyed. There isn’t a computer in the world capable of calculating the price we are paying for “every conceivable view.”

This is the first part of a longer reflection by R.H. Lossin on the relationship between art, artificial intelligence, and emerging forms of hegemony. The second instalment will be published in February.

“Artist Refik Anadol and the Yawanawá People of Brazil Are Debuting an NFT Collection to Protect the Amazon Rainforest,” sponsored post on Artnet (July 25, 2023), https://news.artnet.com/art-world/refik-anadol-yawanawa-impact-one-therme-art-2340856.

Raymond Williams, Culture and Materialism (London: Verso, 1980/2020), 35.

Franco Moretti, quoted in Terry Eagleton, The Ideology of the Aesthetic (London: Blackwell, 1990), 44.

Crawford and Paglen, “The Politics of Images in Machine Learning Training Sets” Excavating.ai, https://excavating.ai/.

Anna Wiener, “Holly Herndon’s Infinite Art,” New Yorker (November 13, 2023), https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2023/11/20/holly-herndons-infinite-art.

Renée Cho, “AI’s Growing Carbon Footprint,” State of the Planet: News from the Columbia Climate School (June 9, 2023), https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2023/06/09/ais-growing-carbon-footprint/.

See “Dialogue between Refik Anadol and Anab Jain,” UNESCO World Heritage Convention, https://whc.unesco.org/en/50-minds/digital/dialogue-2/; and https://nft.refikanadol.com.

Rahul Kumar, “In conversation with Refik Anadol on his AI generated installation 'Glacier Dreams’,” STIR (AprIL 28, 2023), https://www.stirworld.com/inspire-people-in-conversation-with-refik-anadol-on-his-ai-generated-installation-glacier-dreams.

Ibid.

Williams, Culture and Materialism, 43.

Ibid, 38.

Kevin Roose, “The Brilliance and Weirdness of ChatGPT,” New York Times (December 5, 2022), https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/05/technology/chatgpt-ai-twitter.html.