“What is Net Zero?,” National Grid. See ➝.

“What is Net Zero?,” McKinsey & Company, November 28, 2022. See ➝.

The artist duo Cooking Sections provides an excellent analysis of this history in their book Offsetted. Cooking Sections, Offsetted (Hatje Cantz, 2022).

Philip Shabecoff, “U.S. Utility Planting 52 Million Trees,” New York Times, October 12, 1988. See ➝.

Hannah K. Wittman and Cynthia Caron, “Carbon Offsets and Inequality: Social Costs and Co-Benefits in Guatemala and Sri Lanka,” Society & Natural Resources 22, no. 8 (2009): 710-726.

Julie M. Sibbing, “Nowhere Near No-Net Loss,” National Wildlife Foundation. See ➝.

Lisa Friedman and Coral Davenport, “After Supreme Court Forces Its Hand, E.P.A. Crubs Wetlands Protection, New York Times, August 29, 2023. See ➝.

Aruna Chandrasekhar, “Timeline: The 60-year history of carbon offsets,” CarbonBrief, September 25, 2023. See ➝.

Steffen Böhm and Sian Sullivan, eds., Negotiating Climate Change in Crisis (Open Book Publishers, 2021), xlvi.

Carl E. Zipper and Leonard Gilroy, “Sulfur Dioxide Emissions and Market Effects under the Clean Air Act Acid Rain Program,” Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association 48, no. 9 (1998): 829-837.

Chris Hayes, “The New Abolitionism,” The Nation, April 22, 2014. See ➝.

Adam Vaughan, “Most Major Carbon Capture and Storage Projects Haven’t Met Targets,” New Scientist, September 1, 2022. See ➝.

Despite high hopes at the most recent COP28 meeting in 2023 for a regulated framework for carbon markets, an agreement on key rules for carbon trading could not be reached. Matteo Civillini, “Carbon Credits Talks Collapse at Cop28 Over Integrity Concerns,” Climate Change News, December 13, 2023. See ➝.

The Berkley Carbon Trading Project has done a good job in compiling these into a giant spreadsheet containing almost 8000 entries (as of May 2023).

Tesla is probably the most well known case of this. They earned $554 million from offsets in the third quarter of 2023, amounting to around 29% of their total net income. Jennifer L, “Tesla’s Record Carbon Credit Sales Up 94% Year-Over-Year,” Carbon Credits.com, October 19, 2023. See ➝.

Project number GS ID 886, on the Gold Standard registry, see ➝.

William Welch et al., “Calculating Emission Reductions from Jet Engine Washing,” Verified Carbon Standard, VM 0013, Version 1, Sectoral Scope 3. See ➝.

Kevin Starr, “Thirty Million Dollars, a Little Bit of Carbon, and a Lot of Hot Air,” Stanford Social Innovation Review, June 16, 2011. See ➝.

Joseph Winters, “Carbon offsets are ‘riddle with fraud.’ Can new voluntary guidelines fix that?,” Grist, August 2, 2023. See ➝.

Tim Hwang, Subprime attention crisis: Advertising and the time bomb at the heart of the Internet (FSG originals, 2020).

“Berkeley Carbon Trading Project,” Berkeley Public Policy, The Goldman School. See ➝.

Sarah Bracking, “Climate Finance and the Promise of Fake Solutions to Climate Change,” in Böhm and Sullivan, Negotiating Climate Change in Crisis, 255-276.

Desiree Foerster et al., “Whale Falls, Carbon Sinks: Aesthetics and the Anthropocene,” Anthropocene Curriculum, April 22, 2022. See ➝.

Cooking Sections, Offsetted (Hatje Cantz, 2022).

Bram Büscher and Robert Fletcher, “Accumulation by Conservation,” New Political Economy 20, no. 2 (2015): 273-298.

See Mark Dowie, Conservation Refugees: The Hundred-Year Conflict Between Global Conservation and Native Peoples (Cambridge, MA; MIT Press, 2009).

Patrick Greenfield, “The ‘Carbon Pirates’ Preying on Amazon’s Indigenous Communities,” The Guardian, January 21, 2023. See ➝.

Simon Counsell, “Blood Carbon: How a Carbon Offset Scheme Makes Millions from Indigenous Land in Northern Kenya,” Survival International, March 2023. See ➝.

Counsell, “Blood Carbon.”

For a methodology using machine learning, see Project 3331, “Arva Carbon Ready USA” in the Verra Registry.

For methodologies using satellite imagery, drone based photography and LiDar, see Project 2551 “Brazilian Amazon APD Grouped Project,” Project 4042 “Cauaxi REDD+ Grouped Project,” or Project 3761 “Olive Groves for Carbon Farming” in the Verra registry.

For methodologies relying on patrols, see Project 1897 “Ntakata Mountains REDD,” Project 3811 “Chirisa REDD+ Project,” Project 3321 “Hongera Reforestation Project (Mt Kenya and Aberdares),” and Project 2395 “OKI REDD+ Project” in the Verra registry.

“Brazil: Protecting Forests from Illegal Logging,” Water Action Hub. See ➝.

Holly Jean Buck, Ending Fossil Fuels: Why Net Zero Is Not Enough (New York: Verso Books, 2021), chapter 1.

GS ID 7563, “Distribution of Smart Water Bottles to Reduce Plastic Waste,” Gold Standard Impact Registry. See ➝.

Interview with Max Curmi, July 22, 2022. Fragile States. See ➝.

The Indigenous Action Network estimates that successful indigenous-led actions halting the development or expansion of fossil fuel infrastructures in the USA have prevented 779 million metric tons CO2 from being released into the atmosphere over the decade prior to 2019, equivalent to 12% of the USA and Canada’s annual pollution—a figure that dwarfs the emissions reductions achieved by “traditional” offsetting efforts. These actions include halting pipeline projects, like the Atlantic Coast Gas Pipeline, the Energy East Oil Pipeline, and the Keystone XL pipeline, and halting fossil fuel extraction like the Tar Frontier Tar Sands Oil Mine or the opening up of Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge for mining. “Indigenous Resistance Against Carbon,” Indigenous Environmental Network August 2021), 12. See ➝.

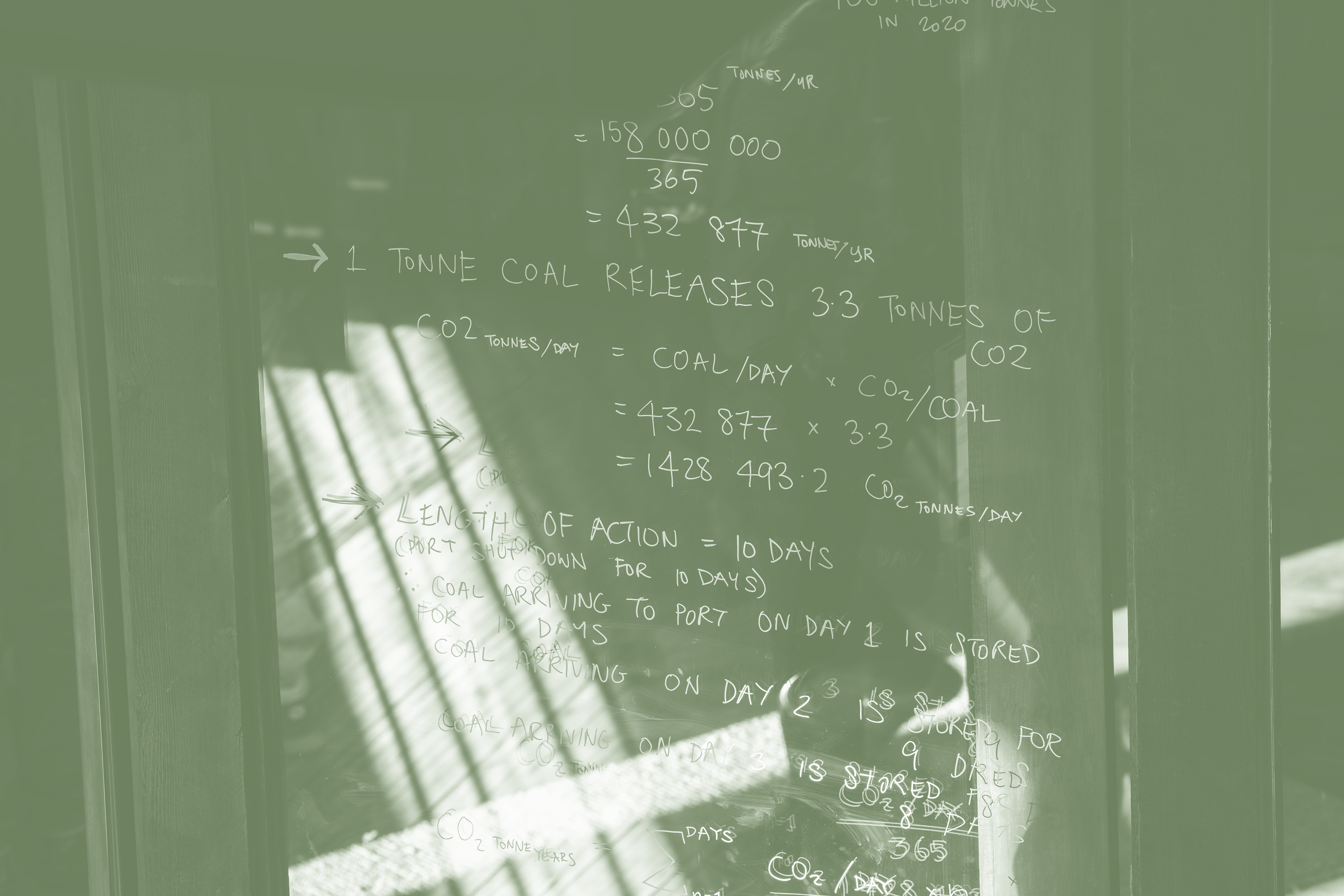

“Industrial Sabotage as Temporary Carbon Storage: A Methodology for Calculating Carbon Credits for Direct Action,” Version 0.1, January 28, 2023. See ➝.

Freya Chay et al., “Unpacking ton-year accounting,” (carbon)plan, January 31, 2022. See ➝.

Tega Brain and Sam Lavigne, “Time Theft as Avoided Emissions.” See ➝.

Tega Brain, “Cold Call (2023).” See ➝.