A friend in Oakland who has been fighting an impending eviction for over a year recently texted me about a new twist in the ongoing saga of her housing struggle. On top of being displaced from her home of over a decade due to no fault of her own, her abusive landlord and his notoriously landlord-friendly lawyer have now also damaged her reputation so much that she was rejected from a different apartment that she had imagined would be her new home post-displacement. Thus, not only is she about to be evicted due to a loophole in tenant law that allows her landlord to kick her out in order to (presumably) sell her rental unit as a fancier condo, she is also now having difficulty locating another place to live because her record has been tarnished. Data has reduced her to a “bad tenant” in the dispossessive machine that is the tenant screening industry. Since the 1970s, punitive blocklisting technology has amalgamated various data sets, including eviction records, criminal records, credit rating data, and more, which can then be packaged and sold as recommendations to landlords on whether someone will be a “good” or “bad tenant.”

My friend had gotten in touch initially because she had been trying to figure out who her landlord actually was. Since the 2008 US foreclosure crisis, there has been an upward trend of corporate investors and real estate speculators purchasing properties through obtuse-sounding shell companies—usually limited liability corporations (LLCs) and limited partnerships (LPs)—which, on top of facilitating tax and liability benefits, also allow landlords to maintain a semblance of anonymity.1 It has become common for corporate landlords to own dozens, if not thousands, of properties through arrays of shell companies. The data and digital infrastructures supporting the corporatization of landlordism have strategically disempowered tenants, making it difficult to connect and organize tenants who share the same landlord. After all, what might happen if all tenants living in units owned by huge Wall Street investment companies such as Blackstone could unite and form a multi-state tenants union? Shell company registration has become a protective measure for corporate landlords to prevent such revolutionary potential.

This hope of mobilizing property data to empower multi-building organizing was in part the impetus for the formation of the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project (AEMP), a housing justice counter-cartography collective that I co-founded in San Francisco in 2013.2 We were committed early on to mapping correlations between evictions and technocapitalist infrastructure, such as “Google bus stops” or public bus depots that private tech companies such as Google, Facebook, Apple, and more had co-opted for private use, in turn inciting a real estate investment frenzy in their surrounding areas.3 Since then, the collective has grown to include chapters in New York City, Los Angeles, and the San Francisco Bay Area, with members producing tools, maps, zines, oral histories, software, murals, community events, and an atlas.4

When we formed in 2013, numerous neighbors, friends, and tenants across the city were facing a brutal wave of evictions instigated by a combination of technocapitalist development, catalyzed by the Silicon Valley software, app, and cloud computing boom, and the predatory real estate industry, eager to capitalize on white collar tech wealth migrating to cities such as San Francisco. Many mid-scale landlords quickly began mimicking Wall Street investment company methods of registering property through LLCs and LPs. As such, early (and ongoing) AEMP work has included gathering and weaving together eviction data, parcel ownership data, corporation registration data, and more to uncover landlord identities, geographies, and eviction histories.

“Sleazy 16,” Anti-Eviction Mapping Project, 2014.

To do this, we first created simple static web pages profiling serial evictors, in which we listed out their LLCs, LPs, and eviction histories. This was based upon rent board public record requests and corporate ownership registration databases from the Secretary of State, as well as manual research grounded in our own experiences as tenant organizers. We also released lists of San Francisco’s worst evictors in grouping such as “The Dirty Dozen,” the “Sleazy Sixteen,” the “Dirty Thirty,” and more.5 These lists were intended to identify the worst evictors, as well as evictors imbricated in the tech industry and those notorious for evicting seniors and people with disabilities. They were intended to supply tenants and housing organizers with information useful in organizing multi-building campaigns, and to reveal identities that landlords had been hoping to safeguard behind shell company webs.

We also created a Pledge Map, in which users could look up addresses and pledge to not rent or purchase buildings with prior eviction histories.6 As we learned from a comrade, the original use of the word “boycott” came from nineteenth century Ireland, when tenants of the abusive English landlord Sir Charles Cunningham Boycott rose up to fight dispossession and land grabbing.7 Sir Boycott had been an English land agent for Lord Erne, who owned 40,000 acres of land in colonized Ireland. The first “boycotts” transpired during Ireland’s Land War of 1879–1882, when, in the midst of dispossession wrought through British colonialism and the devastating Irish Famine, the Irish National Land League formed to campaign for livable rents. Landlords, bailiffs, and landlord agents were all understood to be a class enemy, responsible for evictions and collecting unfair rents. As Charles Stewart Parnell, Leader of the Home Rule League, decried in 1880, “When a man takes a farm from which another has been evicted, you must shun him on the road-side when you meet him, you must shun him in the streets of the town, you must shun him in the shop, you must shun him in the fair green and in the market place, and even in the place of worship.”8 As an exemplar of the land owning propertied class, Boycott began to be targeted by the Irish National Land League in just this way.9 While soldiers rallied to protect Boycott, the tactics nevertheless worked. Soon enough, his name became known throughout Ireland and England, evolving into the word that we use so often today, including in the contemporary Boycott, Divestment, and Sanction efforts against Israeli colonialism in Palestine.

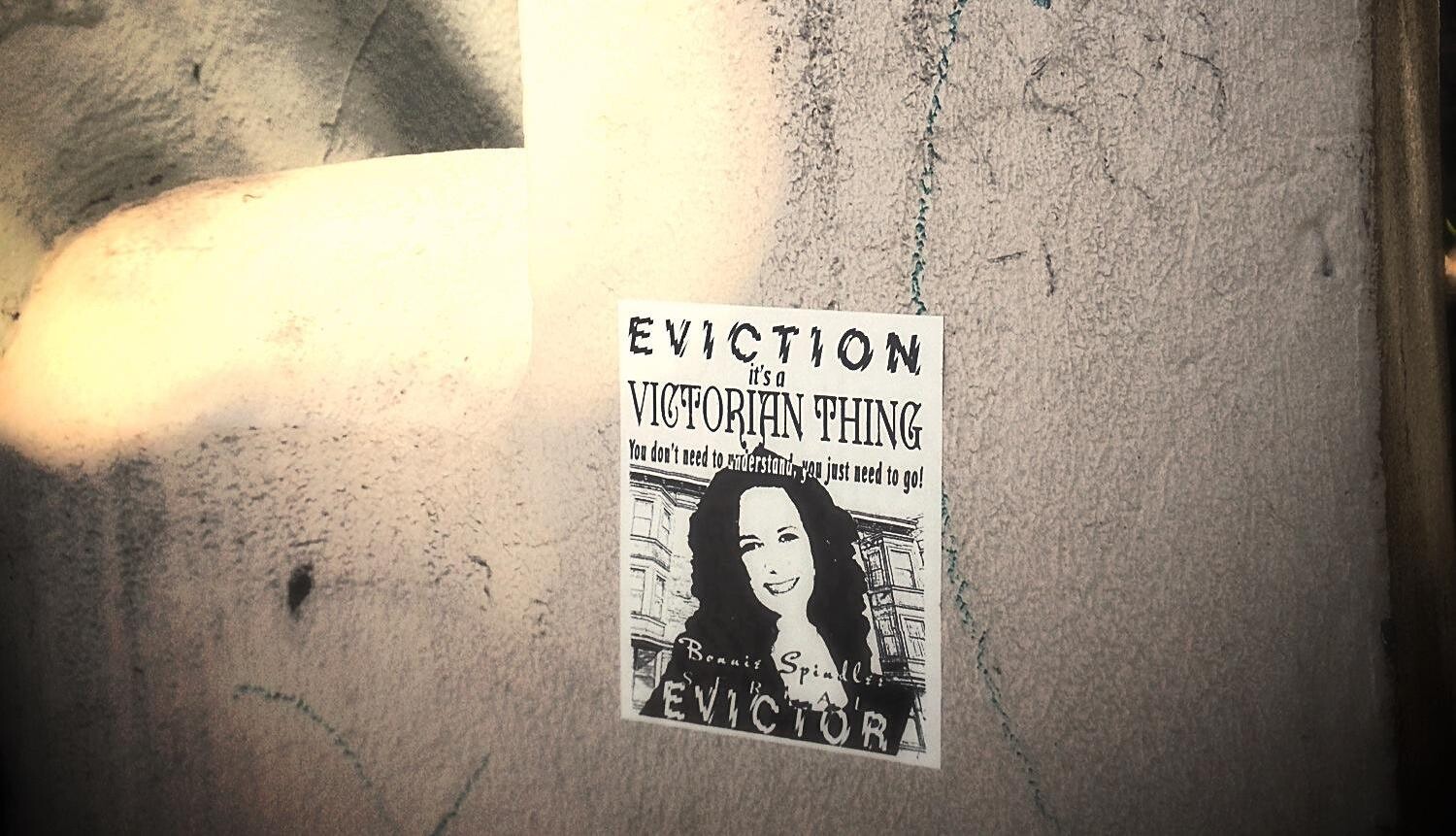

While scholars such as Jo Guldi cite this formative tenant organizing in late-nineteenth century Ireland as the genesis of rent control, even in cities with rent control, evictions still take place. I thus find it important to also consider the wide range of resistant practices that the AEMP and similar groups use today in fighting evictions.10 One of the best strategies for fighting evictions is by using collective power to pressure landlords into rescinding them. Indeed, much of AEMP’s early research on landlords and their abuses aimed to do just this. Demonstrations would be organized outside of evictors’ homes and offices. Members of the San Francisco Anti-Displacement Coalition (which we are a part of) organized a game of “speculator bowling” on the lawn outside of City Hall, where tenants being evicted by serial evictors were able to knock down cardboard bowling pin effigies of their landlords. Sometimes bowling pin cutouts were taken to anti-eviction protests and even to the homes of the landlords responsible. There were also stickers, stencils, and murals made to bring some of our online research and maps to offline space. Groups such as Gay Shame meanwhile organized theatrical direct actions against the lawyers sheltering serial evictors. One action in 2014, “Evict the Evictors,” took place at the offices of Bornstein & Bornstein Law Group—the same lawyers that in 2023 are working with my friend’s landlord in Oakland to evict and blocklist her from future housing.

Demonstration against eviction being carried out by Elba Borgen, replete with an evictor bowling pin of her. Photo by author, 2014.

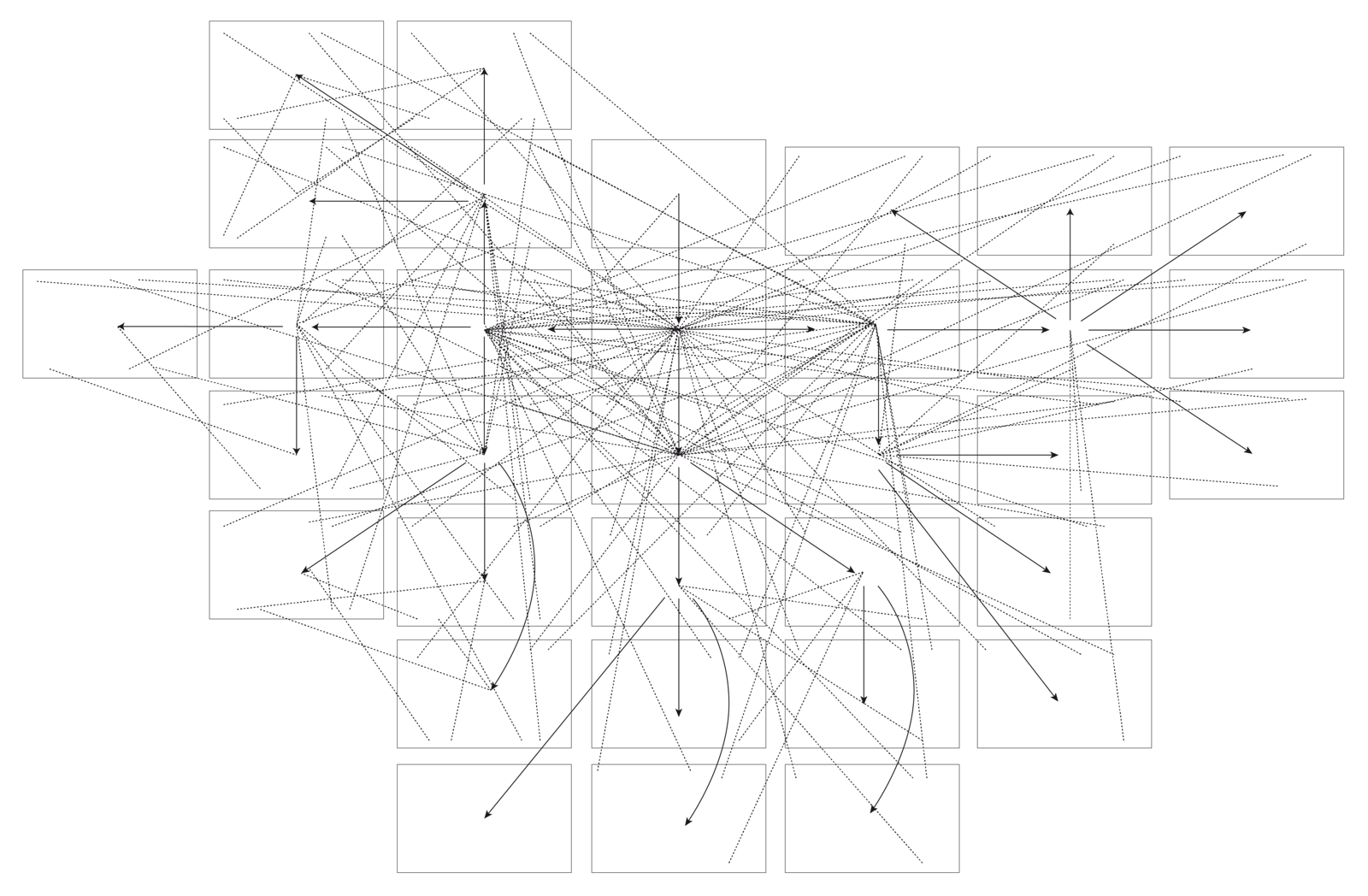

Today, the AEMP maintains a robust team of volunteers who have continued this tradition of landlord identification. Our most recent project is Evictorbook, a tool for Bay Area tenants and tenant organizers to look-up and learn more about property histories, corporate landlords, and the webs of connections between them.11 By merging data that we had been unable to piece together manually in our prior research, Evictorbook allows tenants and tenant organizers to understand complex networks of property ownership and evictions in San Francisco and Oakland.12 In collaboration with the San Francisco Anti-Displacement Coalition, the team has also revivified our existing worst evictor lists through the Worst Evictors of the Bay Area portal, which profiles actors with the highest eviction counts in the two cities.13 This, while modeled off of our earlier static pages and lists, was also inspired by the Worst Evictors NYC site made by JustFix NYC in collaboration with the AEMP and Right to Counsel NYC Coalition.14 When the NYC site was launched, tenants and tenant organizers convened a mock tribunal to hold serial evictors accountable and connect tenants to legal resources.

Tools such as those made by the AEMP and JustFix NYC enable new levels of research into landlord structures and building histories, and they are in good company. A range of similar projects have popped up across the US and beyond, such as Property Praxis in Detroit, Strategic Action for a Just Economy’s Own It in Los Angeles, and the Chicago branch of Democratic Socialists of America’s Find My Landlord.15 While none of these projects are the same, they all are invested in obtaining and mapping property and eviction data in the fight for housing justice on a local scale. These resources can also be useful for enacting boycotts on serial evictors and for empowering tenants to build collective bargaining power. Other projects, such as the Debt Collective’s Tenant Power Toolkit (made in collaboration with the AEMP), aim to build unions of tenants to refuse rental debt.16

At the same time, the landlord technology industry has managed to find ways to enact boycotts on tenants, like what my friend in Oakland is currently experiencing. In other words, landlords have found ways to co-opt strategies initially deployed by tenants. Indeed, tenant screening is a robust and monstrous enterprise, with an estimated nine out of ten US landlords using some form of screening software to blocklist “bad” tenants from obtaining future housing. Eviction and housing court data get merged with criminal record data, credit data, and more by brokers such as LexisNexis, and that data is then woven together by screening companies.

The very first tenant screening company, UD Registry, emerged in California in the 1970s, with others soon following suit. They amalgamated data including court disputes between landlords and tenants, financial data related to bank accounts, bill-paying habits, income and monetary assets, and “lifestyle” information, which could be gathered through a range of methods, such as interviews with past landlords and investigative research. All of this developed alongside advancements in personal computers and spreadsheet software, which enabled faster and cheaper data collection, transmission, access, maintenance, and storage. As Robert Stauffer warned in the 1980s, with advancements in computerized screening, a new level of data creep has been able to materialize in an omniscient machine that can supposedly arbitrate if someone is worthy of housing.17 With dot-com boom digital capital and the wars on crime and terror, the industry exploded in the early 2000s.18 Subsequent advancements in AI and software booms have only compounded industry strength. Today, there are over 2,000 companies active in this largely unregulated industry across the US, and many use algorithms that have been proven to reproduce housing precarity and carcerality, as well as overmatch names of people of color.19

In response, tenants and tenant lawyers have been able to mobilize several states, including California, to mask or expunge court eviction records so that predatory tenant screening companies can no longer access them. Such efforts grew during the Covid-19 pandemic, as did tenant screening methods of collecting data. The company Naborly, for instance, created a portal for landlords to essentially snitch on “delinquent” tenants unable to pay rent.20 This transpired alongside a wider trend of property technology companies capitalizing on pandemic-era fears to unleash new and generally untested systems—many of which, such as facial recognition building-access systems, also reproduce racial biases.21 From new biometric building access and “digital doorman” entry systems to price-setting property valuation software, landlord technologies generally benefit corporate landlords at the expense of tenants whose data becomes fodder for real property accumulation.22

Naborly ad as reported by Didi Rankovic, 2020. See ➝.

Cities and states across the US have enacted eviction data masks and made other efforts to protect tenants’ eviction records and, at times, their criminal and credit records.23 While these efforts are crucial in protecting tenants from tenant-screening-induced blocklisting practices, they also incidentally make it more difficult for tools such as Evictorbook to access eviction data to reveal evictor identities. While Evictorbook relies on municipal rent board petitions vacated of evictee identities (thus revealing landlord intent to evict rather than outcome), we have at times been worried that our tool could be reverse engineered by tenant screening companies eager to identify tenants rather than evictors. However, after numerous debates and workshops with housing lawyers and tenant organizers, we opted to make the site public. This is in part because the tool is fed by publicly available data that any screening company could obtain if they so desired, and because, generally, screening companies only want court records obtained from data brokers and scaled at levels beyond municipalities, making it relatively unlikely that they would absorb data reverse-engineered from a municipally scaled tool.

Nevertheless, organizing boycotts against serial evictors remains an ongoing project. Oftentimes tenants have few options to rent from better actors, especially in a landlord’s market. It is also disempowering that, while we struggle daily to identify who landlords are, making use of multiple data sets connected through complex data pipelines and tools, landlords obtain bounties of data on tenants through the screening industry. Many are also trying to better understand how the screening industry works and what data they grab about tenants, which will require other projects and research. For instance, Landlord Tech Watch, a collective and public-facing project connected to AEMP, produces popular educational materials, reports, and trainings to help teach tenants about tenant screening and other technological systems deployed by landlords to obtain sensitive renter data.24

One of the main challenges moving forward will be finding a way to boycott tenant screening companies and to abolish dispossessive landlord technologies, including invasive biometric and facial recognition technology that is increasingly being implemented in housing for low-income tenants. There is an abundance of work being done in the spirit of early tenant-led rent strikes and boycotting efforts, both in the creation of tools and resources and in the more important work of on-the-ground organizing. Tenant associations and tenant unions have been forming across the country, united through networks such as the Autonomous Tenant Union Network and others.25 Rent strikes proliferated during the Covid-19 pandemic, as did practices of mutual aid and solidarity, which continue today. Boycotts, meanwhile, have endured as an effective organizing tactic in Palestine and beyond.26 All of these efforts extend projects of identifying and holding those responsible for landlord and corporate abuse accountable.

Alexander Ferrer, “Beyond Wall Street Landlords: How Private Equity in the Rental Market Makes Housing Unaffordable, Unstable, and Unhealthy” (Los Angeles: Strategic Action for a Just Economy, 2021). See ➝; Desiree Fields, “Constructing a New Asset Class: Property-Led Financial Accumulation after the Crisis,” Economic Geography 94, no. 2 (March 15, 2018): 118–40.

Anti-Eviction Mapping Project. See ➝.

Manissa M. Maharawal and Erin McElroy, “The Anti-Eviction Mapping Project: Counter Mapping and Oral History Toward Bay Area Housing Justice,” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 108, no. 2 (2018): 380–89.

Anti-Eviction Mapping Project, Counterpoints: A San Francisco Bay Area Atlas of Displacement and Resistance (Oakland: PM Press, 2021).

Anti-Eviction Mapping Project, “The Anti-Eviction Mapping Project Releases ‘The Sleazy 16 - Displacing Tenants for Tourists,’” San Francisco Bay Area Independent Media Center (Indybay), October 7, 2014. See ➝.

Anti-Eviction Mapping Project, “The Ant-Eviction Pledge.” See ➝.

Matthew Wills, “Boycotting Captain Boycott,” JSTOR Daily, April 20, 2018. See ➝.

North of Ireland Family History Society, “The Boycott Relief Expedition,” North Irish Roots 16, no. 2 (2005): 22–25.

Liam Ó Raghallaigh, “Captain Boycott: Man and Myth,” History Ireland 19, no. 1 (2011): 28–31.

Jo Guldi, “The Birth of Rent Control,” Housing (e-flux Architecture, 2020). See ➝.

Evictorbook. See ➝.

Erin McElroy and Azad Amir-Ghassemi, “Evictor Structures: Erin McElroy and Azad Amir-Ghassemi on Fighting Displacement,” Logic Magazine 12, December 20, 2020. See ➝.

Anti‑Eviction Mapping Project and the San Francisco Anti-Displacement Coalition, “The Worst Evictors of San Francisco and Oakland.” See ➝.

Urban Praxis, “Property Praxis,” see ➝; SAJE’s Equitable Development and Land Use Team, “SAJE’s Updated OWN-IT! App Connects Tenants and Housing Justice Activists with Property Info / OWN-IT! actualizado de SAJE! La Aplicación Conecta a Los Inquilines y Activistas de Justicia de Vivienda con Información de La Propiedad,” Strategic Actions for a Just Economy (blog), August 18, 2022, see ➝; Find My Landlord, see ➝.

Tenant Power Toolkit, see ➝.

Robert R. Stauffer, “Tenant Blacklisting: Tenant Screening Services and the Right to Privacy Note,” Harvard Journal on Legislation 24, no. 1 (1987): 239–314.

Rebecca Oyama, “Do Not (Re)Enter: The Rise of Criminal Background Tenant Screening as a Violation of the Fair Housing Act,” Michigan Journal of Race and Law 15, no. 1 (January 1, 2009): 181–222.

Lauren Kirchner and Matthew Goldstein, “How Automated Background Checks Freeze Out Renters,” New York Times, May 28, 2020, see ➝; Wonyoung So, “Which Information Matters? Measuring Landlord Assessment of Tenant Screening Reports,” Housing Policy Debate 33, no. 6 (November 2, 2023): 1484–1510.

Didi Rankovici, “Naborly Asks Landlords to Report If Tenants Are ‘Delinquent’ on April Rent, to Build a Profile on Them,” Reclaim The Net (blog), April 4, 2020. See ➝.

Erin McElroy, Wonyoung So, and Nicole Weber, “Keeping an Eye on Landlord Tech,” Shelterforce (blog), March 25, 2021. See ➝.

Erin McElroy and Manon Vergerio, “Automating Gentrification: Landlord Technologies and Housing Justice Organizing in New York City Homes,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 40, no. 4 (August 1, 2022): 607–26; Heather Vogell, “Rent Going Up? One Company’s Algorithm Could Be Why,” ProPublica, October 15, 2022. See ➝.

Erin McElroy, “Dis/Possessory Data Politics: From Tenant Screening to Anti-Eviction Organizing,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 47, no. 1 (2023): 54–70; Anna Reosti, “‘We Go Totally Subjective’: Discretion, Discrimination, and Tenant Screening in a Landlord’s Market,” Law & Social Inquiry 45, no. 3 (August 2020): 618–57.

Anti-Eviction Lab, “Landlord Tech Watch.” See ➝.

Autonomous Tenants Union Network (ATUN). See ➝.

Palestinian BDS National Committee (BNC), “Act Now Against These Companies Profiting from the Genocide of the Palestinian People,” BDS Movement, November 5, 2023. See ➝.

Spatial Computing is a collaboration with the M.S. in Computational Design Practices Program (MSCDP) at the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation (GSAPP) at Columbia University.