State-led Sinofuturity

In December 2021, on a forested hill at the edge of an expansive infrastructural development area called Gui’an New Area, the telecoms giant Huawei unveiled an eighteenth-century-style European town that looks quite a bit like Prague.1 Streets and boulevards are paved in white stone and lit by antique streetlamps. Granite balustrades flank a double staircase that leads from the main square up to the “rathaus” building, which overlooks concentric terraces of townhouses whose pastel facades and terracotta roofs are illuminated at night like a Germanic fairytale. A large moat, filled by a waterfall cascading down a craggy rock face, encircles the entire complex.

Theme-park European architecture is nothing new in twenty-first-century China, nor in Gui’an New Area, which already offers a Swiss-style scenic village as a nearby tourist attraction. However, look more closely at the buildings in the new Czech town and you’ll notice that their windows are in fact air-vents, thrumming and heaving with the high-pitched rush of server racks and cooling fans. The water tumbling down the artificial cliffside and circulating in the moat is part of a cooling system for transferring heat away from the machinery. This is Huawei’s new Cloud Data Center, which follows the company’s tradition of building its Chinese campuses in a range of historic European styles, from medieval to neoclassical, replete with spires and cornices. The most unusual architectural feature of the Gui’an development is a vast, anachronistic cuboid covered in a “Mondrian” pattern, built to hold Huawei’s physical archives.

Covering an area of almost seventy-five acres, the Gui’an development is the largest data center Huawei has built so far, and is designed to hold almost a million servers hosting cloud services for 170 countries.2 The campus is also a global training center for Huawei employees and contractors, who are brought to Guizhou for technical bootcamps. When I visited in May 2023, a few bored but cheerful Brazilian and Nigerian engineers were wandering the town’s empty streets, along with some elderly locals who had stopped by to see what the fuss was about.

In 2014, the southwestern province of Guizhou, a historically poor and mountainous area, beat out rival regions to become China’s first “Big Data Comprehensive Pilot Zone,” as part of a national directive to develop the region—which is otherwise best known as an exporter of tobacco, spirits, and coal—into the infrastructural backbone of the country’s data industry. Since then, vast investment has poured into the province. Thousands of miles of highway and high-speed rail tunnel through the mountains. Driving through the province can feel vertiginous: of the hundred highest bridges in the world, almost half are in Guizhou, and almost all were built in the last fifteen years.

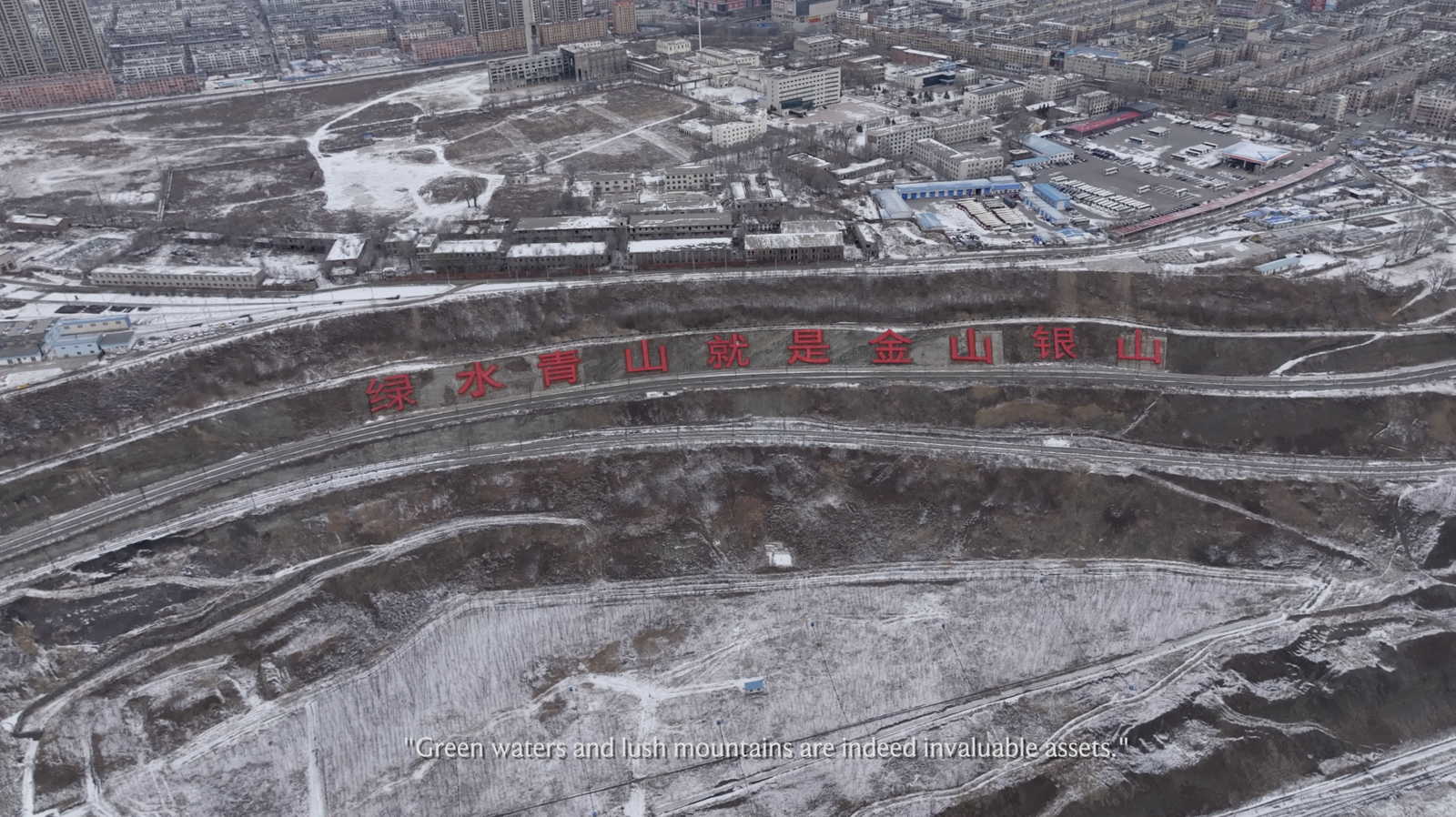

In 2015, Xi Jinping visited Gui’an New Area to inaugurate the province’s transformation into China’s “Big Data Valley,” exemplifying the central government’s goal to establish “high quality social and economic development,” ubiquitously advertised through socialist-style slogans plastered on highways and city streets.3

The blinding pace of multipronged infrastructure development has sought to transform the region’s image into a peculiar, oriental Switzerland, at once idyllic, tourist-friendly, and techno-economically advanced: the very image of “high quality development.”4 Guizhou Normal University even has a Swiss Research Center that studies Switzerland as a successful model of mountainous regional development.5 FAST—the world’s largest filled-aperture radio telescope—is here, a key national scientific asset and a popular tourist spot (complete with a VR experience center). So is the Oriental Science Fiction Gorge, a billion-dollar theme park featuring towering mecha figures. “Guizhou’s super computational power enables the audience to watch Wandering Earth II ten years in advance,” one headline fawned.6 Guizhou, it has been ordained, shall leap into the future.

With backing from Beijing and its “Government Guidance” funds (a combination of state-partnered venture funds and tax and real estate incentives), the previously nonexistent data industry in Guizhou has rapidly expanded tenfold, to over 9,000 firms in 2022, accounting for a third of the region’s GDP.7 The province now hosts a Big Data Expo trade show, a Global Data Exchange, and other flagship industry hubs aimed at drawing international investment.

The most visible signal of the region’s shift into a data hub came in 2018, when Apple handed over its iCloud operations in China to a local partner, Guizhou-Cloud Big Data (GCBD), in accordance with a 2017 law requiring domestic users’ data to be stored within China’s borders. A notification declaring the handover literally pushed Guizhou into the palms of all Apple users in China. (Amazon Web Services, whose Chinese market is far smaller than Apple’s, sold its infrastructure to a Beijing partner the previous year.)

Huawei, whose founder Ren Zhengfei was born in the province, is not the only Chinese tech giant building major infrastructure in Gui’an. Neighboring Huawei’s data center is a large hill into which Tencent has dug deep caverns that hold 300,000 servers of its own.8 Like an inversion of Huawei’s European-style citadel, Tencent’s subterranean fortress comprises five fifteen-meter-high tunnels supported by vast concrete buttresses built to the standards of a bomb shelter.

Gui’an New Area is more than a pilot zone for technological investment. It’s also part of a wider project of embedding infrastructural logic into non-urban landscapes, as opposed to the metropolitan Central-Business-District-style innovation “zone” seen in cities across the country. As the scholar Tim Oakes argues, Gui’an’s development model is that of an “infrastructural grid” that produces “not so much cities as networks and operational landscapes.”9

The New Area imagines a future in which data is paramount. Sensor networks are being threaded throughout the town that will integrate ecological monitoring (such as rainfall and river flow) and logistical management into the planned computational grid. An algorithmic surveillance system called Sky Net, which closely tracks drivers and pedestrians, is already installed. This is a test site for a kind of large-scale technocratic landscaping that erodes old distinctions between urban and rural. Oakes calls it “a transition from landscape to datascape.”10

The Coast and the Interior

As the anthropologist James C. Scott details in The Art of Not Being Governed, the province of Guizhou is part of Zomia, the highland zone home to numerous ethnic minorities who have historically resisted political cooptation by lowland state administrations, whether Vietnamese or Imperial Chinese.11 Of its thirty-five-million residents, around a third are ethnic minorities, such as Miao and Yao, whose ways of life sit on the periphery of central socio-economic policy-making. The tension between this historical remoteness and contemporary plans for connectivity positions Guizhou in China’s nation-building narrative as both an aspirational vessel of modernization and its unassimilated other.12

The mounds of karst that undulate across Guizhou’s landscape are highly porous. Often, they are covered in vegetation, growing from thin soils that drain rapidly through the rock. Within, they are pocked by caverns and threaded through by tunnels carved by millennia of rain. Most of the province is at high altitude, cooler than much of the rest of southern China. These conditions are bad for agriculture, but great for data centers.

“Data Valley” is the latest in a line of grand infrastructural visions aimed at integrating Guizhou into the wider Chinese national project. Far from the eastern seaboard and easily defended atop the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau, physical and human geography have long made it indigestible to central planning technocracy—a frontier between coast and interior, simultaneously underexploited and secure. Since the foundation of the People’s Republic of China, Guizhou has been the target of successive visions of state-led sinofuturity, which have developed the province as unevenly as its karst landscape.

While coastal residents might consider Guizhou a hinterland, it features prominently in the making of modern Chinese national identity. In 1935, in the midst of the Long March—the Red Army’s legendary two-year retreat from the southeastern coast to the interior—it was in Zunyi, less than 200 kilometers north of Gui’an, that Mao emerged as the leader of the Communist Party. Three decades later, fearing attack from the Kuomintang in Taiwan, top-secret “third front” mega-projects were built in the region to maintain a vast industrial base: a last defensive barrier should the communists need to stage a retreat from the “first” and “second” fronts of Shanghai and Suzhou.13

Third front construction across Guizhou and Sichuan in the 1960s became a symbol of socialist modernity. Indeed, at the height of Third World internationalism, the same hastily trained brigades of Red Army engineers who had built steel mills and factories across the southwestern mountains were dispatched to East Africa to lead the construction of the Tanzania-Zambia railroad, a historical beacon of socialist fraternity and China’s largest infrastructure investment in Africa.

At home, the strategic goal of the third front was to build a vast, dispersed, self-sufficient industrial network encompassing almost the entirety of inland China, constructed at unprecedented human and economic cost and scale, extending from Hubei-Shaanxi in the east to Yunnan-Guizhou in the south and Gansu in the north—an area roughly the size of Western Europe. Between 1965 and 1980, 100,000 urban and rural workers migrated from across China to Guizhou alone, descendants of whom, known as “third front children,” still identify with this industrial heritage.14

Near the end of the Maoist era, as investments were being refocused towards the industrializing north and east, the southwest territories came to be seen as a source of energy. Rich in coal and hydropower, Yunnan, Guizhou, and Sichuan were a key node of the West-East Electricity Transfer Project, one of several infrastructure megaprojects aimed at directing resources from China’s west to incipient economic powerhouses like the Pearl River Delta. Although a central policy to “open up the west” was undertaken in the 2000s, Guizhou and its neighboring provinces were to serve primarily as support for the rapid industrialization of the coasts.

From Badlands to Data Valley

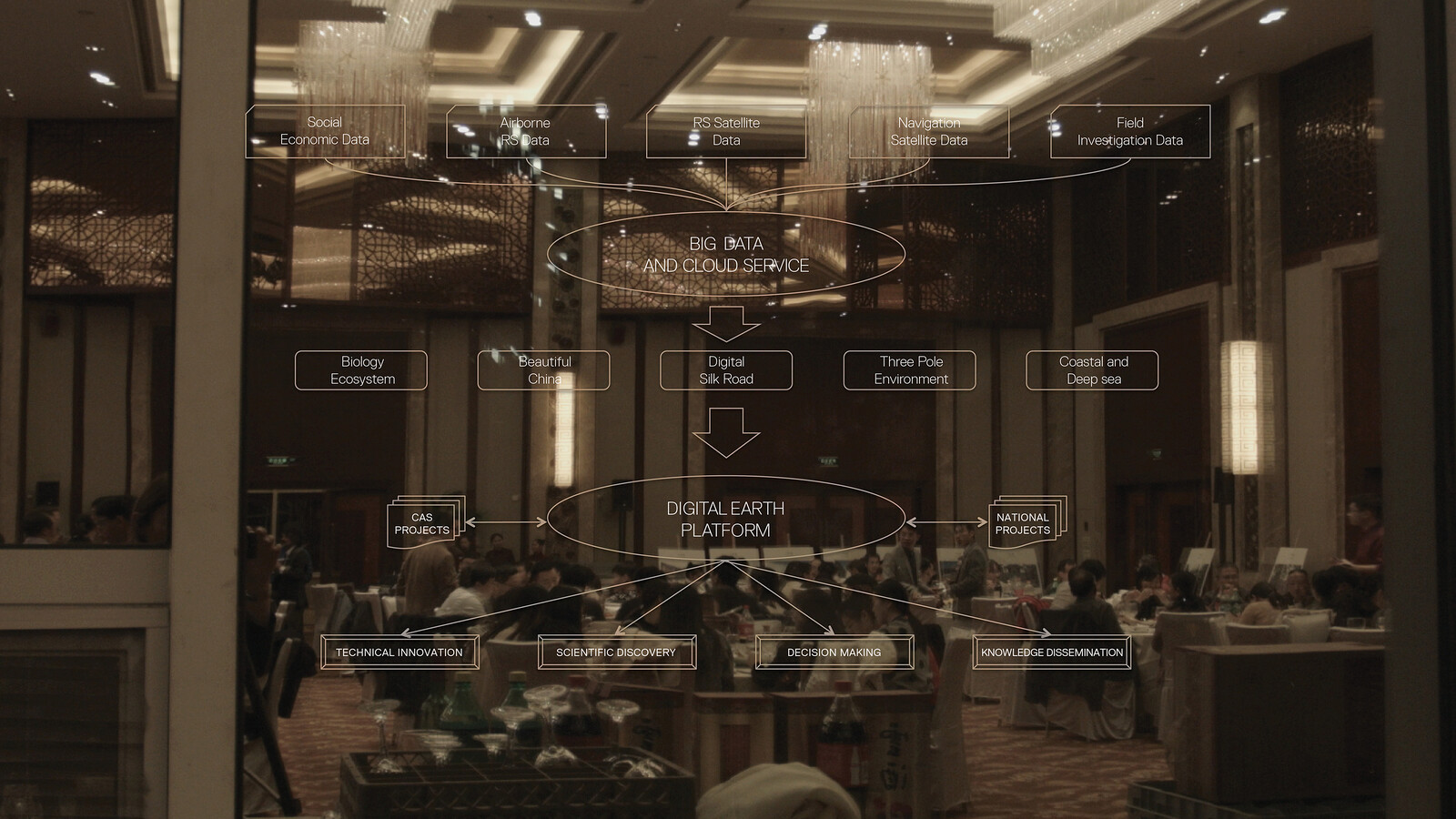

In early 2022, Beijing announced “Eastern Data, Western Computing” (EDWC), a plan to build eight “hub nodes” of data center infrastructure predominantly in western provinces, including the “underdeveloped” regions of Inner Mongolia, Gansu, and Guizhou. As a macroscopic restructuring of the nation’s computing infrastructure, EDWC is designed to address the intensive computational (and real estate) demands of China’s coastal technology hubs by distributing computational capacity through the western interior, bolstering its economies in turn. Name-checking American computer scientists John McCarthy and Ian Foster, formative figures in the development of cloud computing, the National Development and Reform Commission claims that the program “elevates computing resources, for the first time, to the level of foundational resources like water, electricity, and gas.”15

As with the strategic rationale of the third front’s factories in the mountains, the rationale for EDWC’s focus on Guizhou is geographical and geological: low earthquake risk, cool temperatures, and access to cheap energy. (For a while, cheap hydropower also made Guizhou a global hotspot for bitcoin mining, before the practice was outlawed in China.) In becoming Data Valley, Guizhou’s cultural and geophysical image has been reanimated and transformed into the computational backbone of the Chinese state technology stack.

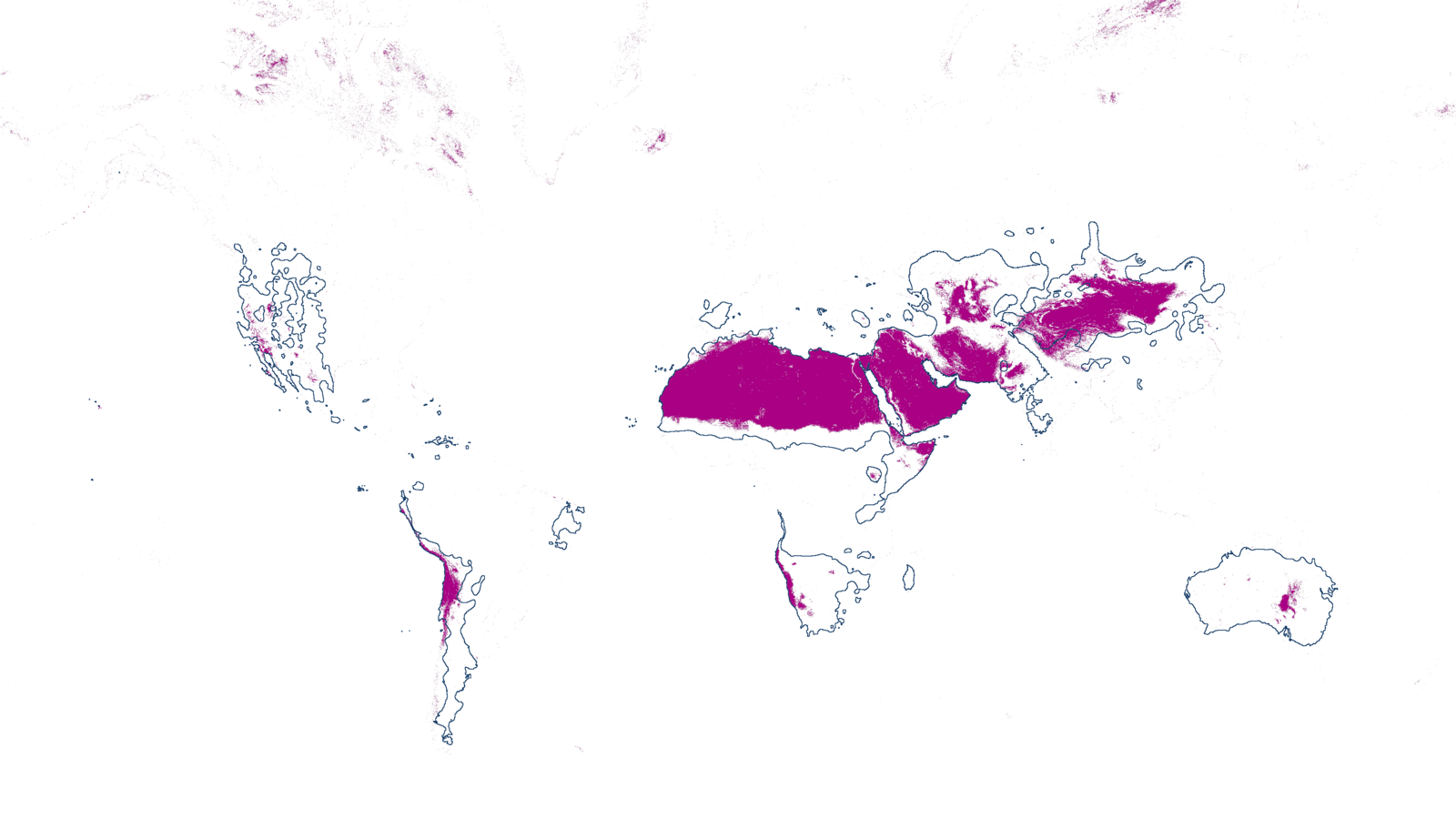

Against the backdrop of recent US-China trade wars and technology sanctions, EDWC figures not only as an industrial development policy but also as a blueprint for technological sovereignty, dotting the country’s interior with decentralized nodes of the national computing grid. Since Deng Xiaoping’s 1986 “863 program,” a policy for “indigenous innovation” inspired by Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative, technological advances in computing have figured prominently as part of the national goal of technological independence. At a time of renewed global focus on industrial strategy, EDWC highlights the state’s role in marshalling China’s corporate technology giants towards techno-political nation-building—towards becoming a “Cyber-Superpower” (网络强国, DigiChina).

The tech economy—whether in China or the US—is often associated with unfettered markets. Yet just like in Silicon Valley, which owes its existence to state infrastructure, Guizhou’s nascent Data Valley continues the largely uninterrupted trajectory of China’s state-directed technology strategy in accordance with national and geopolitical objectives. Indeed, as Darcy Pan points out, China’s cloud strategy is not only focused on furthering domestic industries, but also on influencing global cloud computing standards.16 As the national narrative shifts from defensive capability and infrastructural security to innovation-led sinofuturity, the promise of Guizhou’s elevation to the cloud is not only a story of provincial development, but also a reiteration of the marginal territory’s historic role as a hidden abode of sovereignty.

The Cloud on the Ground

What such grand infrastructural re-imaginings mean for Guizhou’s present and future remains unclear. The state-guided expansion of Tencent and Huawei’s huge data centers benefits from local resources, but this new computing capacity continues to serve a value chain that is overwhelmingly tied to the coasts. Having recently experienced decades of outward migration to more prosperous provinces, Guizhou lacks the skilled labor force required for integrating “Western computation” into its provincial economy.

Bainiaohe Digital Town, a village near Guiyang that trains and employs vocational students in the arduous work of classifying image datasets used for training autonomous vehicle systems, was touted as a “boon to the region’s young people and their impoverished families” in 2018. By 2023, it was nearly empty; the low-wage data-cleaning economy apparently collapsed during the pandemic. Resignation notices could be found tacked to work terminals.

Thousands of corollary data-related companies have cropped up in the Gui’an region, but one of the biggest challenges remains developing applications and markets for turning data processing capacity into products and services. Without a meaningful throughput of “hot data,” the extensive capacity being constructed in the region risks becoming a remote form of cold storage. Rendering graphics for the entertainment industry is a bright spot, but planned smart-city grids and environmental-monitoring stations have yet to be built.

Much of the earlier momentum was driven by the province’s then-governor, Chen Min’er, a rising star and Xi protégé who left in 2017 to lead the more prestigious government of Chongqing. The province developed rapidly during Chen’s four-year tenure: a high-speed rail journey from Shanghai to Guiyang now takes only nine hours—the equivalent of leaving London in the morning and arriving in Bucharest by late afternoon—and the Guiyang skyline is dominated by the familiar sight of towering skyscrapers-in-progress. One employee I met at a leading Guizhou cloud firm moved there from a “Big Four” consulting firm, a sign that young professionals may be returning to their home province with an eye on policy-driven opportunities, particularly given the overwhelming competition in coastal metropolises.

But the furious infrastructural expansion that buoyed Chen’s political career also made Guizhou one of the most indebted provinces in all of China following the nationwide property crash in 2020, a crisis from which it is still reeling. As recently as January 2024, the admission of a leading Guizhou official to wasting billions of dollars featured prominently in a documentary about Xi’s anti-corruption campaign.17 As economist Michael Pettis points out, the poster child of China’s investment excesses may well become a model for the deep economic adjustments the country will now need to make.18

As China enters a new economic and geopolitical era, integrating marginal provinces such as Guizhou into its national project is a test of the Chinese state’s ability to empower and to cohere. One day, perhaps, provinces like Guizhou will no longer be seen as underdeveloped and mere providers of labor, electricity, and materials powering the coastal engine. Instead, these hinterlands are becoming critical nodes in China’s project of becoming a “Cyber Superpower.”

“Huawei opens data center in Guian New Area,” Guiyang.gov (English), December 22, 2021, ➝.

“Huawei builds data storage center in Guizhou,” Xinhuanet, August 2, 2017, ➝.

As said by Lu Yongzheng during the “Guizhou: Carrying forward the spirit of Zunyi Meeting and embarking on a Long March of the new era” event on May 20, 2021, ➝.

This phrase and variations on it are Xi Jinping-era trademarks. See: Xinhua, “What to know about China’s high-quality development,” State Council Information Office, People’s Republic of China, March 18, 2024, ➝.

“Consul General of Switzerland in Chengdu Visited Guizhou Normal University,” November 19, 2020, ➝.

Huanqiu.com, “Guizhou’s super computational power enables the audience to watch the Wandering Earth II ten years in advance,” PR Newswire, March 18, 2023, ➝.

Government Guidance funds can be between national banks, local government investment vehicles, and private capital. See: Yifan Wei, Yuen Yuen Ang, and Nan Jia, “The Promise and Pitfalls of Government Guidance Funds in China,” The China Quarterly 256 (2023): 939–59; China.org.cn, “Guizhou: a decade of China’s big data valley,” PRNewswire, October 14, 2022, ➝.

Xinhua, “China turns ancient caves into big data treasury,” China Daily, June 3, 2023, ➝.

Tim Oakes, ‘“The National New Area as an Infrastructure Space: Urbanization and the New Regime of Circulation in China,”‘ The China Quarterly 255 (September 2023): 162.

Tim Oakes, “From Creation City to Infrastructural Urbanism” in Infrastructure and the Remaking of Asia, eds. Max Hirsh and Till Mostowlansky (Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2023), 159.

James C. Scott, The Art of Not Being Governed (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010).

Tim Oakes and Zuo Zhenting, “‘Remoteness and Connectivity,” 426, ‘in The Routledge Handbook of Highland Asia, eds. Jelle J. P. Wouters and Michael T. Heneise (London: Routledge, 2022).

Barry Naughton, ‘“The Third Front: Defence Industrialization in the Chinese Interior,” The China Quarterly 115 (1988): 352. See also Covell F. Meyskens, Mao’s Third Front: The Militarization of Cold War China (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020), 37.

Meyskens, Mao’s Third Front, appendix A.2.

“Eastern Data Western Calculation,” National Development and Reform Commission, March 7, 2022, ➝.

Darcy Pan, ‘“Storing Data on the Margins: Making State and Infrastructure in Southwest China,” Information, Communication & Society 25, no. 16 (December 2022): 2419.

Amanda Lee and Mia Nulimaimaiti, “China’s debt-ridden Guizhou faces reckoning after years of splashing out on pricey projects,” South China Morning Post, March 9, 2024, ➝.

Michael Pettis (@michaelxpettis), “5/5 Just as Guizhou in the past has been the poster child for investment excesses, it is likely in the future to become a model for the way in which much of the Chinese economy will have to adjust from these excesses.” Twitter, March 9, 2024, ➝.

New Silk Roads is a project by e-flux Architecture in collaboration with the Critical Media Lab at the Basel Academy of Art and Design FHNW and Noema Magazine (2024), and Aformal Academy with the support of Design Trust and Digital Earth (2020).