November 16–December 15, 2024

Collectives have played an influential role in the history of Indonesian art, from the 1930s, when the twenty-member PERSAGI, or Persatuan Ahli-Ahli Gambar Indonesia (Union of Indonesian Painters), boldly declared a nationalist, anti-colonial agenda, to the now-famous ruangrupa, whose methods of resource-sharing and knowledge-building have become influential touchstones for a more egalitarian art world.

In contrast to these collectives associated with political and social action, this exhibition features an informal group of four artists from or based in Bali—Edmondo Zanolini, I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih, Dewa Raram and Dewa Putu—whose concerns are profoundly personal and inward-looking. In the 1990s, they formed a commune-like group (some of them lived together) where they made art and formed a space to explore their fantasies, trauma, and subconscious. Although the styles of their output were very different, their works displayed similar motifs and subject matter, which could come from specific visual prompts (like photographs) which they used to stimulate creativity, or a more spontaneous process. The resultant body of work on show here are the strange, fascinating fruits of their collective dreaming.

“MuMoToMo” is an abbreviation of the artists’ names. The “ringleader”—whose house formed the gathering-place for this group—is Edmondo Zanolini (Mondo), an Italian artist with a background in theater, whose travels through Asia led him to Bali in the 1990s. But the most famous is I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih, or Murni, who has been posthumously celebrated over the past decade for her bold and playful depictions of female sexuality rendered in a flat, graphic style. Born in Bali to a poor family, and sexually abused by her father, she was sent to be a domestic helper in Jakarta at the age of 10. Later, she returned to Bali to work as a silversmith, married, and then divorced, because her husband wanted to take a second wife due to her inability to bear children. Single again, she looked for work as a housekeeper, and was employed by Mondo; he introduced her to painting, and the pair eventually became lovers. In her lifetime, she was represented by a women-only, Ubud-based gallery called Seniwati Gallery, and enjoyed modest success, touring internationally in group and solo shows. Her star has risen steadily in the years after her death from cancer in 2006, at the age of 39.

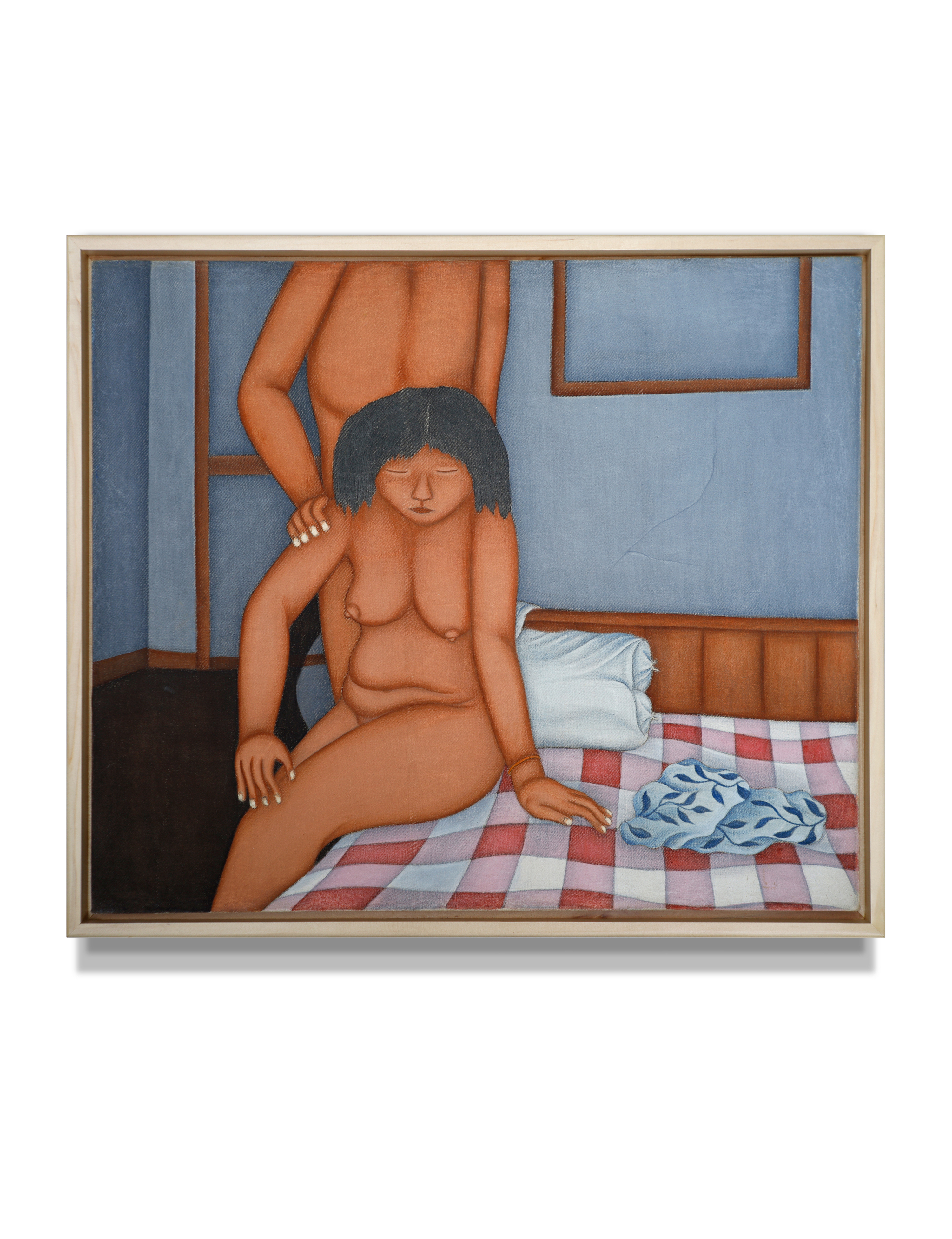

Joining in the artmaking sessions was Dewa Raram (Oototol), who used Chinese paint to create a black-and-white oeuvre exploring his private symbology of figures in military uniform. Lastly, there is Dewa Putu (Mokoh), who was trained in the wayang style of Balinese art, a flat, 2D aesthetic inspired by traditional puppet shows. After making a career out of depicting idyllic scenes of village life, he reached a creative plateau due to depression, according to Mondo’s account in the catalogue. At Mondo’s house, he taught Murni and Oototol how to paint. Their sense of freedom encouraged him to indulge his own fantasies, and his sexually explicit tableaux are shown here, such as Dundun (1991), which depicts a woman fellating a man.

“MuMoToMo” is rather literally organized into thematic sections, such as “The Gift and Curse of Life” and “The Serpent: Myths and Traditions.” But the experience feels less schematic and more id-led, with echoes and correspondences pinging throughout. What the subheaders provide are entry points into a fluid, libidinous, and cross-pollinating network of ideas between the four artists. In one section called “Digits and Digital”, ostensibly about mobile phones, Mondo’s painting Grace Hotel (1998) depicts a woman with a serene expression wrapped up in sheets, sitting on a chair and holding a corded phone to her ear. There’s an atmosphere of post-coital relaxation. Of a more celibate cast is Oototol’s untitled and undated ink-on-canvas, showing a row of women in military uniform, each holding a phone to their ear. With one hand on their thighs, slightly leaning forward with an air of polite, feminine attention, they resemble air stewardesses coming to take your order. The phones are upside down, with the cord on top, so the scene has a slight sense of derangement. In Murni’s canvases, mobile phones are unabashedly phallic objects. In the bubblegum-colored My Friend and HP Kesukaanku: Kesayangan (My Favorite Mobile Phone: Dearest) (both 2004), she depicts them nestled in the palm of her hand with a shaft and a head—and buttons.

I also enjoyed the genealogical stories that trace the flow of ideas that morph from one artist’s canvas to the next. Mondo’s watercolor He Wonders About Being Considered A King or a Prince (1995) is a doodly and diffuse composition with various fantastical figures in states of transformation. From the top of a gigantic head sprouts a smaller man; a flying green bird-like creature bites the giant face’s jaw, and so on. A few years later, Murni painted Impianku (My Dream, 1999), allegedly from her own nighttime vision, a work with clear correspondences to one part of Mondo’s painting, albeit simplified and intensified. It is a strange vision of impregnation by a succubus/god/alien figure. A nude woman is lying down. Above her is an amorphous entity that stretches an appendage to her breast and another to her swollen belly. Green wiggly lines in the background trace out a kind of energetic transfer that plays on the nerves of my body as I view them.

If it’s not clear already, the exhibition’s chief draw is Murni, whose works, executed in her signature style of flat, simple forms in bold outlines and bright colors, operate in the register of the squalid-sacred: dicks, vaginas, breasts, high heels and sharp nails in all manner of hybridizations, permutations, and penetrations. Sexuality can be pain or pleasure, weakness or empowerment, sordid or spiritual. Or both, as seen in My Action (2003), which depicts a woman from behind, peeling back her buttocks—a pornographic cliche of sexual invitation—while a large, heavy penis dangles between her legs. The block colors and reduced forms of the composition endow the work with a talismanic quality.

It is well-documented in the critical literature how the childhood sexual abuse she suffered manifested in her paintings. The exhibition captures the changes in her perspective over her career. An early work, Kenangan Terakhir Bersama Bapak (Last Memory with Father) (1996), depicts a woman on the phone, her hanging hair obscuring her face. In the foreground is a shriveled and scaly lizard-like creature with six legs. All over the painting are cobalt blue splotches of paint, as if hastily stamped over with a wet sponge: global contamination. A few years later, she made Terima Kasih Ayah (Thank You Father) (2003), where the figure of a woman sits cross-legged within the outline of a large penis and testicles, her white head echoing the white head of the phallus. The penis here has become a womb; the site of pain transformed into a place of birth. Her remarkable journey as an artist speaks to the nurture of her fellow travelers, and the exhibition in general testifies to the deep reservoirs of strength and creativity that can be accessed through association with kindred spirits.