“I always arrive at something new out of desperation.” This was Anna Zemánková’s description of how she began to make drawings in satin when she ran out of paper. The resulting collages use textile colors, ballpoint pen, and acrylic to create the shapes of flowers and plants. They are tender and surprising, a new and shimmering nature. Zemánková, born in Austria-Hungary in 1908, was self-taught: a dental assistant who began making art after a bout of depression following the death of one of her children. Drawings of flowers might traditionally be defined as “women’s work”; better to say that it was the conditions under which she made art—pressured to take a trade rather than go to art school, raising a family, only making work as a response to personal tragedy—that defined her labor as such.

Eight of Zemánková’s flower pieces, which were also shown at the 2013 and 2024 editions of the Venice Biennale, were brought to London by Sophie Tappeiner as part of Condo, a project in which twenty-two London galleries host twenty-seven peer spaces from around the world. The match-ups vary. The Approach handed their annex space to Vienna’s Tappeiner and their upstairs to Zurich gallery Philipp Zollinger, showing huge abstract paintings by Renée Levi and small cartoonlike ceramic-and-tin sculptures by Cassidy Toner. It was a coherent and balanced presentation, if a bit safe: an older and a younger artist, paintings on the walls and sculptures on plinths.

Elsewhere, the meetings are more surprising. Brunette Coleman hosts New York gallery Francis Irv in a two-artist presentation: Rachel Fäth is showing two sculptures, Locker 5 and Locker 6 (both 2024), cubes of steel made of found metal scraps salvaged from buildings in New York. Alongside these are three works by Zazou Roddam, including found crystal door handles encased in a vertical plexiglass box (Lot2454/Lot 5152, 2024–25) and Desert Rose (2024–25), a group of aluminum fans, and a doorbell welded to look like a flower. The five works on view barely fill the small space, but Fäth’s work is a cityscape on the floor—a compressed history of material and labor—and Roddam’s a making-weird of the everyday. Even though there is little to see, this sparse presentation is dense with ideas and information.

Another pairing that becomes a dialogue is on view at Studio M., where Maureen Paley welcomed Air de Paris. Fourteen framed xerograph prints by Pati Hill—of red petals, a pair of scissors, a single glove—hang facing a Wolfgang Tillmans photograph of a disused photocopier in the artist’s studio (CLC 800, dismantled, a, 2011). The machine is broken up, its insides splayed, dysfunctional but still drawing attention. Together, the works speak of technology and its promises and how, in the eyes of an artist, any image-making mechanism is full of possibility. Some petals printed with red toner, the sight of something bound to fade, in front of a device that can no longer be fixed. Also: all things fail in the end.

Hollybush Gardens and Gordon Robichaux present a more literal meeting: Janet Olivia Henry and Cynthia Hawkins. Henry’s Cynthia and Janet at JAM on 57th Street (2024) is a diorama reimagining the first time the two artists met at Just Above Midtown gallery in New York. Seeing Henry and Hawkins’s works side-by-side—half a century after JAM was founded by filmmaker and activist Linda Goode Bryant to promote the work of artists of color—is testament to the lasting impact a gallery and a community space can make.

Galleries can also present the conditions in which artists work. At Sylvia Kouvali, Beirut’s Marfa showed seven artists from Lebanon whose work reflects their geopolitical context. Ahmad Ghossein’s How to make your money sell (2023) includes three sculptures of thin wooden beams covered in Lebanese banknotes, accompanied by a framed bank statement: hyper-inflation has made them practically worthless, and the work is priced to the value of Ghossein’s life savings before the lira collapsed. A number of the works—like “64 Dusks,” a series of photos of dusk in London that is part of Rania Stephan’s ongoing project on the life and mysterious end of celebrated Egyptian actor Soad Hosni, who died in the city in 2001, and Lamia Joreige’s storyboard-like small paintings Uncertain Times, Background for a script 1–15 (2024), which imagine the daily life of an Ottoman soldier in Jerusalem—use narrative as a way of bridging time and place.

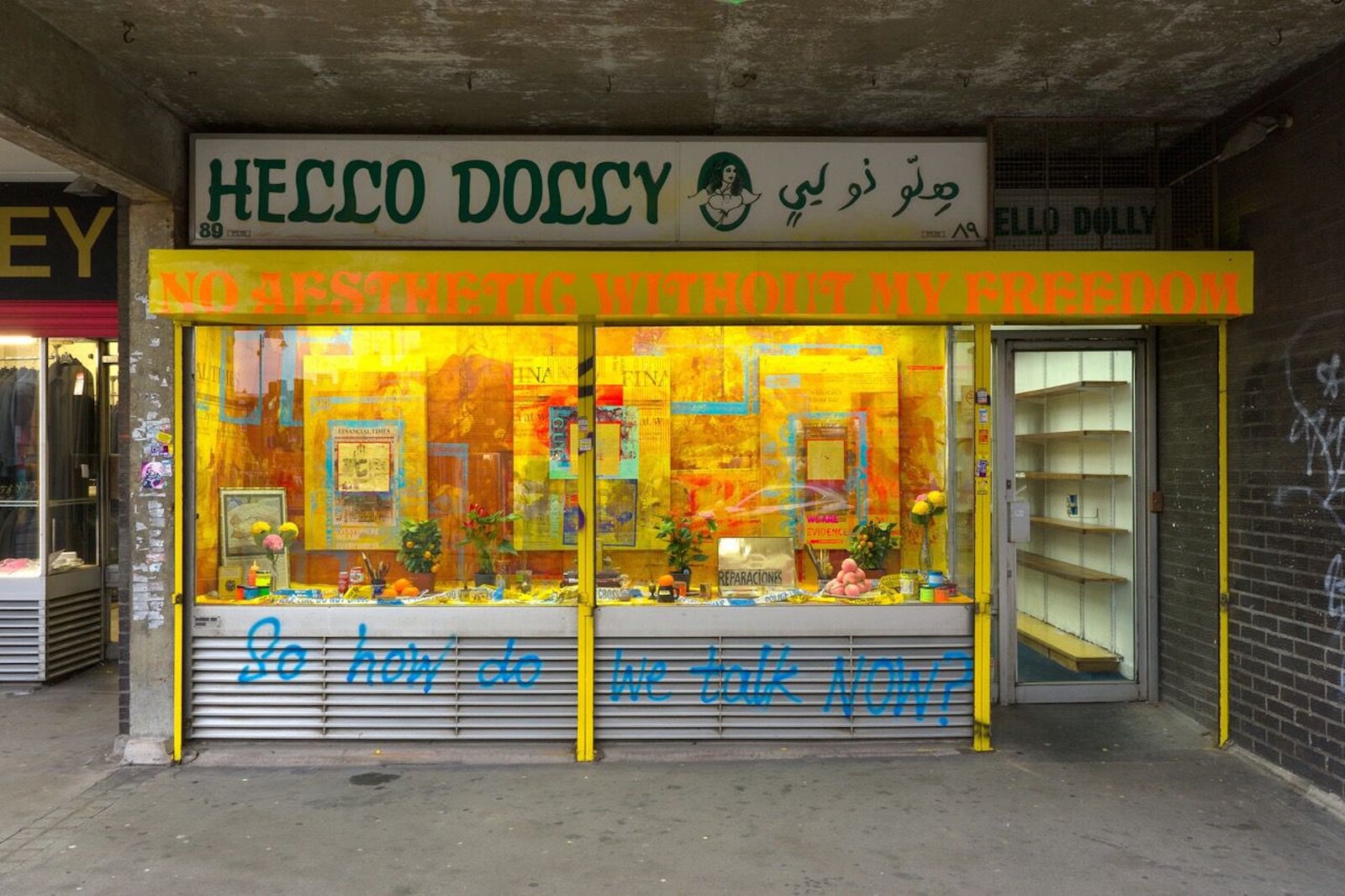

The commercial units in the housing estate where Public Gallery is located used to have an additional floor upstairs, with a separate entrance. These extra rooms were converted into apartments, and the staircases leading to them blocked in cement a few stairs up. Abbas Zahedi’s Weeping Diwani (2020), rendered in anti-climb paint and masking tape on a salvaged boiler panel, is presented in one of these claustrophobic limbo spaces. In the same group show, titled “00:00:01,” Steph Huang’s Prawn Fried Rice (2025) is a small sculpture showing a glass shrimp reaching into two Spam cans filled with rice. Irreverent, yes, but also evidence of how quotidian things carry deep culturally specific meanings, if you pay a lot of attention to them. The textile shop that used to occupy the gallery’s space was called “Hello Dolly,” and its sign, in English and Arabic, remains. It hangs above a site-specific installation in the shop window by Mandy El-Sayegh, a London-based artist of Malaysian-Chinese and Palestinian heritage. It comprises artifacts of personal and symbolic significance—paintbrushes, incense, oranges—with police tape strewn around them. It is completed by another sign: “no aesthetic without my freedom.”

El-Sayegh’s assortment of small, loaded objects presented for passersby in a repurposed shop encapsulates this edition of Condo. The nature of the citywide collaboration—with small and mid-sized international galleries traveling, and often transporting works, to London—means that there is an emphasis on easily portable objects: sculptures on shelves, works on paper (or satin), or small two-dimensional pieces like the two patchwork canvases by Kern Samuel, brought by New York gallery Derosia and shown at Soft Opening, inspired by the Gee’s Bend quilting tradition. Despite the overwhelming number of galleries and artists involved, I find myself focused on single works, on details, on moments. Things that can be carried by people and bring meaning with them, things that are small yet can stand for so much.