In a fit allegory for a country Luis Pérez-Oramas once defined as a “wasteland republic,” one of Venezuela’s greatest twentieth-century artworks remains out of sight, its status uncertain.1 Reticulárea—an environment made of metal nets, based on triangular modules, that hang from the ceiling and surround the viewer—was realized by the German-born artist Gego (1912–94), who arrived in Caracas in 1939 with a degree in Architecture and Engineering but no more than a few words of Spanish. First shown at the Museo de Bellas Artes of Caracas in June 1969, it was thereafter remade for several exhibitions until a room was dedicated to it in 1980. Since 2002, it has rarely been available for viewing, a limitation, attributed to conservation issues, which seems to have become permanent around 2009 (exact records are unavailable). In 2017 the work was deinstalled, losing both its form and its place, and rendering its absence total.

Despite this, the work has been germinal to contemporary Venezuelan art: its photographic record securing its reputation as a pioneering aesthetic proposal. The recent flowering of Gego’s international renown as a radical abstractionist who revolutionized postwar sculpture rests on the work’s refusal of volume, mass, monumentality, and its embrace of a situated spatiality and a decentered logic that has—since a version of it was exhibited in Frankfurt in 1982—been associated with the rhizome.2

Visitors were invited to wander through Gego’s meshes and weaves of stainless steel, iron, and floristry wire: this modality of communal viewership accords with the collective making of the nets, and recalls the workshop logic that informed Gego’s architectural training in Stuttgart between 1932 and 1938. The latter also informed the small furniture workshop she ran in Caracas in the 1940s, and recurred in her pedagogical endeavors at the city’s School of Architecture and the Institute of Design. In all these creative spaces, Gego worked with others and with her hands; from play, tinkering, and experimenting, she built the foundation of a practice that translated into the knotting of reticular nets with the help of assistants, students, and friends.

The process of assembling the reticuláreas was demanding. It involved the cutting and twisting of metal rods (with pliers), which then needed to be hooked to one another, pursuing an expansive network logic that defied the structural transparency of geometric abstraction. When Gego made and installed the Reticulárea in 1969, she thanked seven helpers in the accompanying brochure alongside Miguel Arroyo, director of the museum, for suggesting the idea of an environment in lieu of thinking about the nets as individual works. In both its viewing and its making, the Reticulárea relies on collective experience. It’s a great shame that a younger generation has been deprived of its powerful formulation of communal spectatorship and collaborative production.

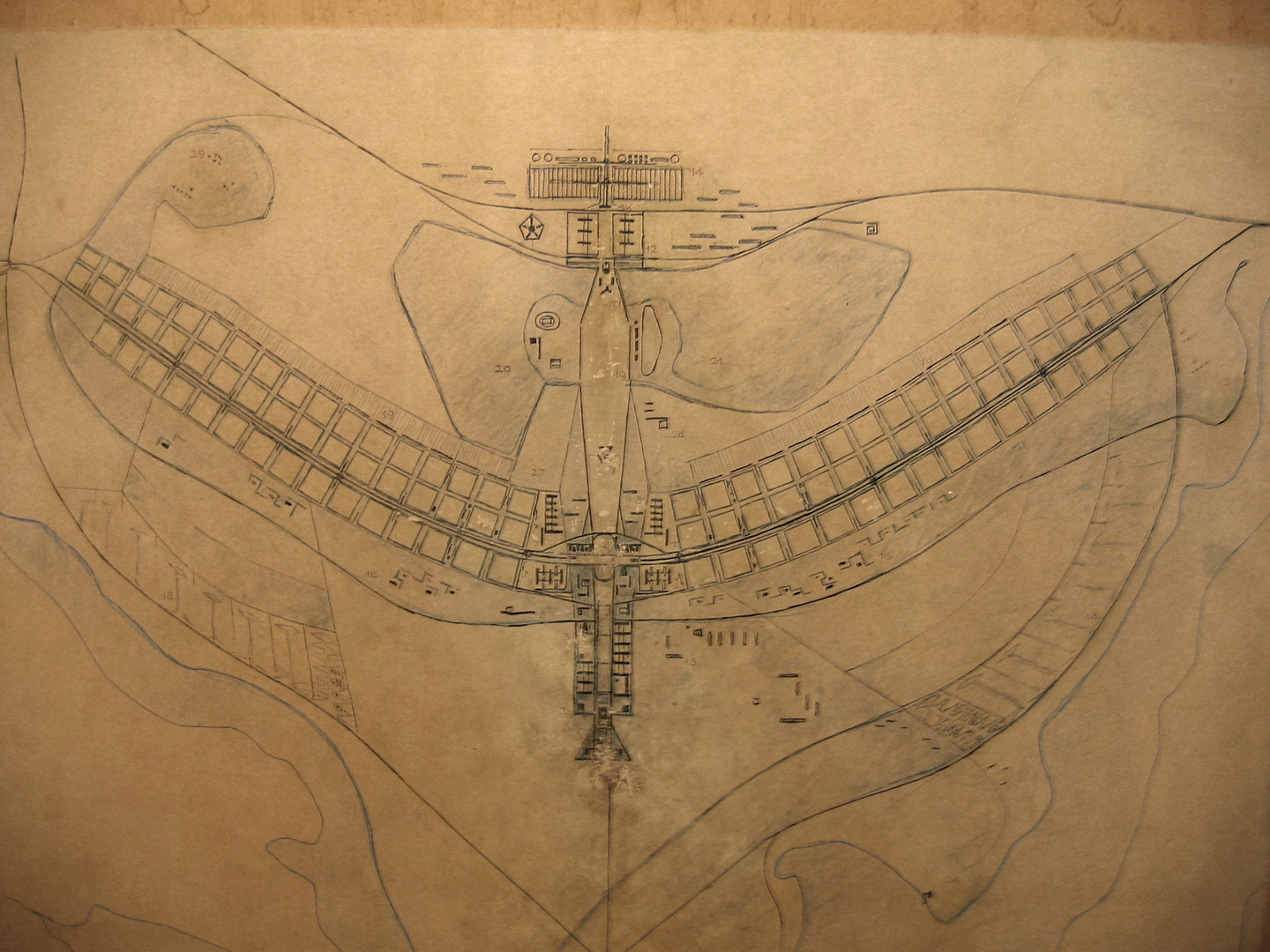

Collective Reticulárea: Cartografías Comunes. Participatory project by Miguel Braceli. Exhibition at the Sala Mendoza in Caracas, 2024. Curated by Fundación Gego and Stefanie Reisinger. Courtesy by LA ESCUELA___. Photo by Josseline Chalbaud.

Last year, to reanimate these two aspects of the work, Venezuelan artist Miguel Braceli conceived of a collective performative action in which artists and students, at home and abroad, were invited, through an open call that required the coordinated effort of institutions and colleagues, to create the triangular modules that would form a new work inspired by Gego’s Reticulárea.3 Modules were collected and transported to Caracas, and then connected to constitute a Collective Reticulárea exhibited at the Sala Mendoza—a historically important exhibition space founded in 1956. Braceli trained as an architect in the same school where Gego, in the 1960s, taught the Basic Course that introduced students to the study of materials, techniques, and tools of design. Formerly an architect and educator, he also pivoted away from the construction of the built environment to develop a practice founded on cooperative learning.

During the last decade, triggered by a national crisis in which notions of planning and development have been rendered moot, the city has become his stage. There, he has led poetic actions which reflect on political, social and ecological precarity, breaking free from the confines of the classroom and reflecting on gesture, materials, action, and territory outside of the nation’s failing institutions. In numerous performances made between 2014 and 2024, in which people carried banners, meters of fabric, tents, and other pliable materials, Braceli occupied the public spaces of the university and the city. In giving visibility and materiality to these gatherings, these works reclaimed civic action and pondered the ruins of national sovereignty.

With the Reticulárea Colectiva: Cartografías Comunes, Braceli materializes the void left by a work that figures—in its multivalence and complexity—the diasporic condition of the Venezuelan people today. Gego herself was a dislocated subject—she was born Gertrud Goldschmidt in Hamburg, to a bourgeois Jewish family—and her Reticulárea can be seen as a decentered body lacking core and delineation. This reading chimes with her dismissal of sculpture as mass and volume, and her embrace of the word bicho (bug) to describe the airy and irregular weaves of metal that she began producing in 1969.4 Alternatively, the Reticulárea can be read as a network of lines in which no center or hierarchy makes possible a stationary point of view. Instead of a mastering viewer and a controlling gaze, both Reticulárea and Reticulárea Colectiva articulate situational contingency.

Educational project with pupils of the Escuela Comunitaria SHEKINAH, San Blas, Petare, Caracas, November 2023. Courtesy of LA ESCUELA___. Photo by Jesús Briceño.

Departing from these various evocations of the 1969 Reticulárea, Braceli began working with space, materials, and bodies to rematerialize and resignify a work decoupled from its place and audience. Several of the triangular modules exhibited at the Sala Mendoza came out of the experimental Taller X department at the School of Architecture of the Universidad Central in which Braceli studied and taught between 2001 and 2018. As with the open call to artists living outside Venezuela, the goal was to reactivate the decentralized and connective demeanor of the absent Reticulárea. This would take place through the dispersed gestures of these new makers and the use of materials readily available in their diverse settings.

A group from the School of Architecture used wood, wires, and cords; in the neighborhood of Petare, during a related educational activity, kids worked with plastic to create a vast net that sheltered the patio of their elementary school. Interregional collaborations with universities in Merida and design students on the island of Margarita followed, and their contributions joined those of artists who sent their pieces from institutional and non-institutional centers in the Americas and Europe.

As with Gego’s Reticulárea, whose knotting techniques oscillated between elegant and regular and messy and spontaneous, the individual contributions to Reticulárea Colectiva are idiosyncratic but also fuse easily with others. While numerous sections utilized metals—copper, aluminum, steel, and wire (artist Muu Blanco contributed a segment made of “sweet wire wrapped in white felt and colored threads”)—others were composed in wood, bamboo, velvet, rubber, plastic, paper, corn leaves, and hair. Vernacular materials (such as hangers, frayed fabric, straws, cardboard and pencils) abounded, and tie wraps (used by the police to restrain “unruly” individuals at assemblies and protests) were a favorite connector.

Collective Reticulárea: Cartografías Comunes. Participant: Elena Saraceni Anzola. Materials: Synthetic Hair fibre, various metals, PVC and botanical wires. Courtesy of LA ESCUELA___.

Some of these elements attest to a culture of precarity that already concerned Gego’s students in the 1970s. In this too, the Reticulárea Colectiva pays homage to the alternative grammars that informed her work. The socio-ecological project Arte y Vida (art and life), founded in 1972 by students from the Institute of Design Fundación Neumann where Gego taught a seminar in Spatial Relations, called for the restoration of sensuality to everyday life. In collaboration with the community of the coastal town of Tarma (where Gego lived between 1953 and 1956, and kept a house until the end of her life), Arte y Vida fostered a program of learning on site and from one another, unlearning in order to relearn, and exploring alternatives to the indoctrinating forces (school, media, the political and economic system) that have destroyed the environment and displaced communal work. Through workshops that used material leftovers from the city and native elements, participants sought to recreate indigenous technologies in the areas of agriculture and artisanal production.5

Almost fifty years later, Braceli put forward in 2020 (as his MFA thesis) a proposal that resonated with the efforts of Arte y Vida. The Naked School was not only a space outside the white cube logic and promotional machinery that many art schools replicate and model for students. It also aimed to resituate artistic production in direct proximity with “the social and political contexts that surround them.” In 2022, the Naked School morphed into LA ESCUELA___, a digital platform and a pedagogical structure of rotating partnerships based on radical learning and situated publicness: it is one of Braceli’s collaborators in this project.6

Collective Reticulárea: Cartografías Comunes. Participatory project by Miguel Braceli. Exhibition at the Sala Mendoza in Caracas, 2024. Curated by Fundación Gego and Stefanie Reisinger. Courtesy by LA ESCUELA___. Photo by Josseline Chalbaud.

The reorienting of the constructive—a rejection of the precision, rationality, and structural transparency generally associated with postwar geometric abstraction—has been acknowledged as one of Gego’s main contributions to twentieth-century sculpture. Braceli’s project advances the absent Reticulárea’s many lessons around collaboration, collectivity, and decentralization. But to me, the manner of the work’s reactivation is its most pressing elucidation: here is a model of planetarity and “deborderization” appropriate to an historical moment of profound polarization. Instead of self-sufficiency and permanence, both Reticuláreas—the one dismantled and sequestered, and the one produced by nomadic gestures that weave hybrid materialities—insist on the expansive net as an emancipatory model for a world in need of connections. As Édouard Glissant observed in 1990: “The tale of errantry is the tale of Relation […] of worldwide entanglement.” Reticulárea figures forth the ontological instability that the relational animates—one in which identity (for a diaspora of eight million Venezuelans) is “no longer completely within the root but also in Relation.”7

see Luis Pérez-Oramas, La República Baldia: Crónica de una falacia revolucionaria (1995-2014) (Caracas: La hoja del norte, 2018).

A term first used in relation to the work by architect Christian Thiel in a letter to Gego dated September 16, 1983.

In collaboration with Sala Mendoza, the Gego Foundation, Siemens Foundation and curated by the Gego Foundation and Stefanie Reisinger. Developed by LA ESCUELA___.

In Venezuela the word bicho is a colloquial, pejorative interjection used to refer to humble, unimportant things. Gego used it across the three logbooks that catalogue the artist’s three-dimensional work as a rebuff of sculpture as an index of verticality, volume, mass, and proportion. The related word bichero alludes to heterogeneous groupings of things and both words reject denomination. Most importantly bicho bespoke a form of localized thinking and doing that did not preexist the work but emerged from its conditions of existence.

It is around this time that residual materials from her workshop become central to Gego’s work. See my “Residues,” in Gego: Weaving the Space In Between (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2023), 219–237.

https://laescuela.art/en (LA ESCUELA___was founded by Braceli and Siemens Stiftung)

Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, trans. Betsy Wing (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997), 18, 118.