In 1913, a year before the Panama Canal was completed, the journalist Frederic J. Haskin wrote that “the conquest of the Isthmian barrier was the conquest of the mosquito.”1 This was a period when America’s westward expansion was eclipsed by overseas military conquest, with the US having gone to war in 1898 with Spain and by 1902 taken control of Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam. President Theodore Roosevelt intensified this ongoing project of US interference in Central America and the Caribbean, and supported a coup d’état in the Colombian province of Panama by US-friendly businessmen in 1903.2 The newly independent nation granted the US outsized political and military influence in the region, in large part due to the creation of the US Panama Canal Zone: a ten-mile-wide strip of US territory cutting through the territory. As the site of the construction and subsequent operation of the transisthmian canal that continues in operation today, the territory was a testing ground for a unique kind of architecture that reconfigured the relationship between humans and mosquitoes.3

The connection between mosquito control and the United States’ imperial conquest can be seen in the work of William C. Gorgas, the Alabama-born Army surgeon who led efforts to eradicate yellow fever and malaria— both mosquito-borne diseases—during the first US occupation of Cuba (1898–1902) and was subsequently appointed Chief Sanitary Officer of in Panama. For Gorgas, controlling yellow fever and malaria took on historic, imperial dimensions. Reflecting on his work, Gorgas claimed that he had “made sanitary discoveries that will enable man to return from the temperate regions to which he was forced to migrate long ages ago, and again live and develop in his natural home, the tropics.”4 Nevertheless, mosquito control efforts were not simply about making work in hot climates tolerable for white US employees from more temperate zones. How workers lived and the way housing was designed demonstrated overlapping US policies, prevailing perceptions of the tropical environment, and the conflicts between engineers and workers of various social classes, races, and ethnicities. In particular, the dwellings erected for the Isthmian Canal Commission (ICC) conjoined the management of mosquitos with manipulating the interactions between people of different races and social classes.

Groundwork

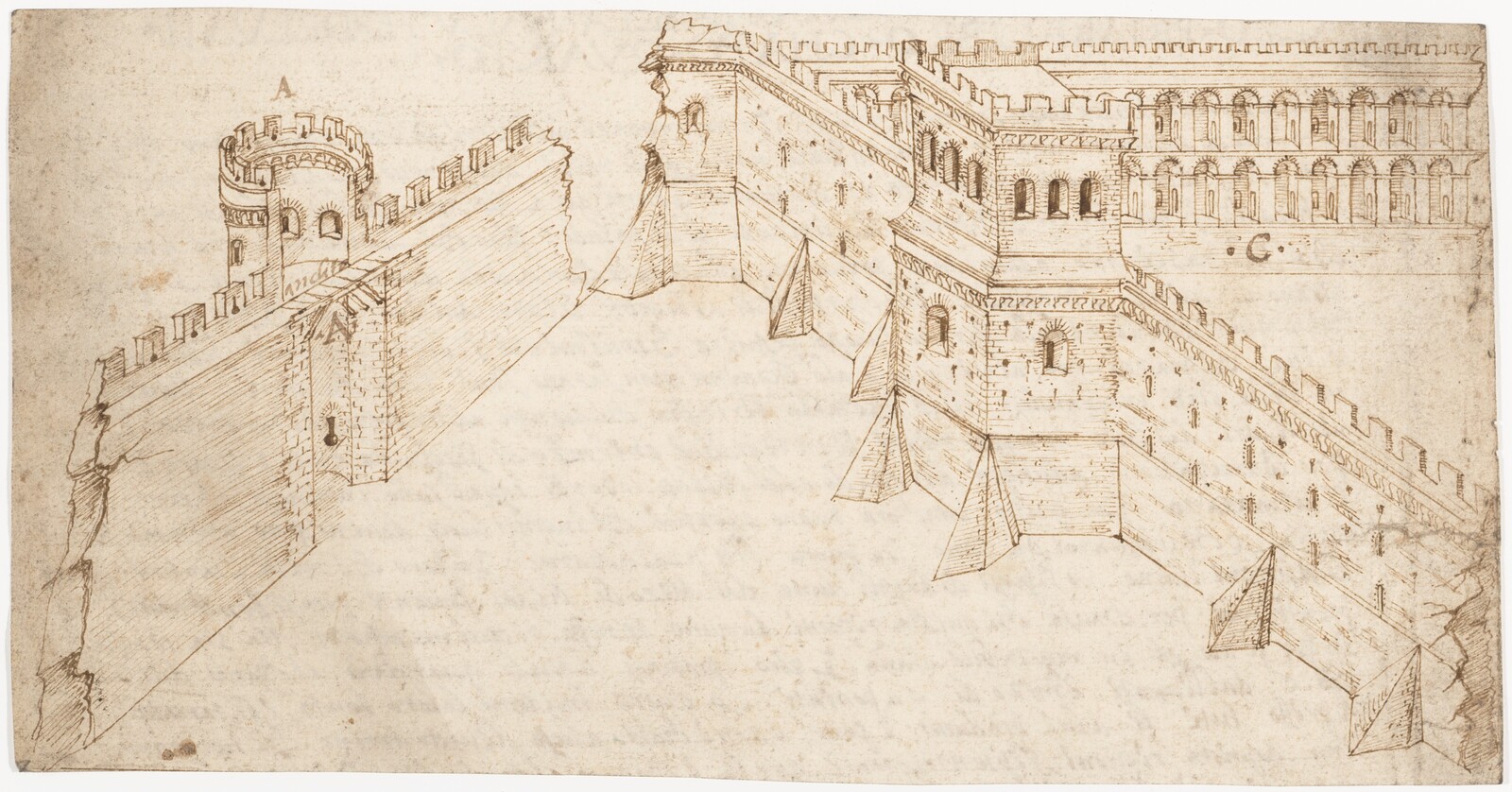

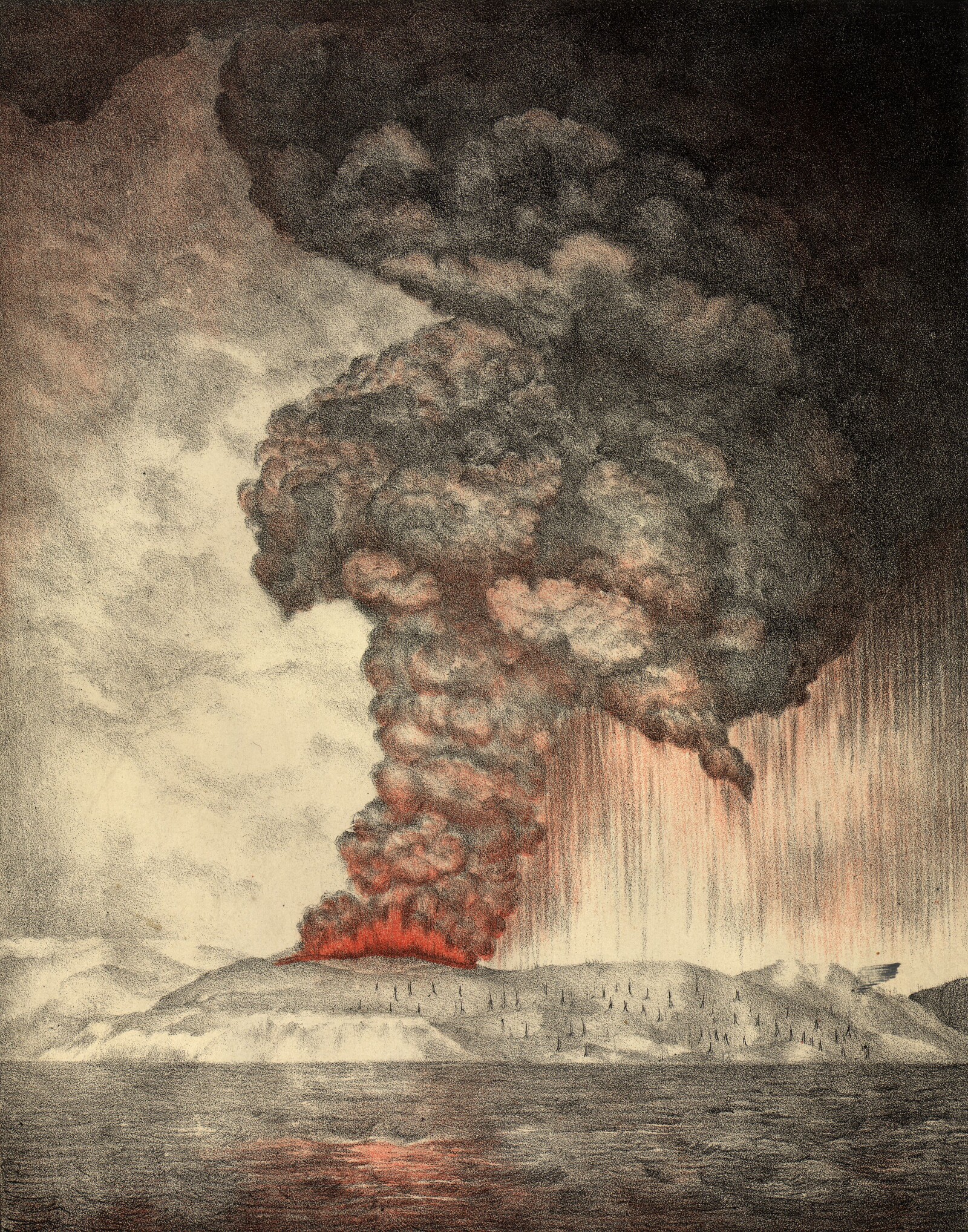

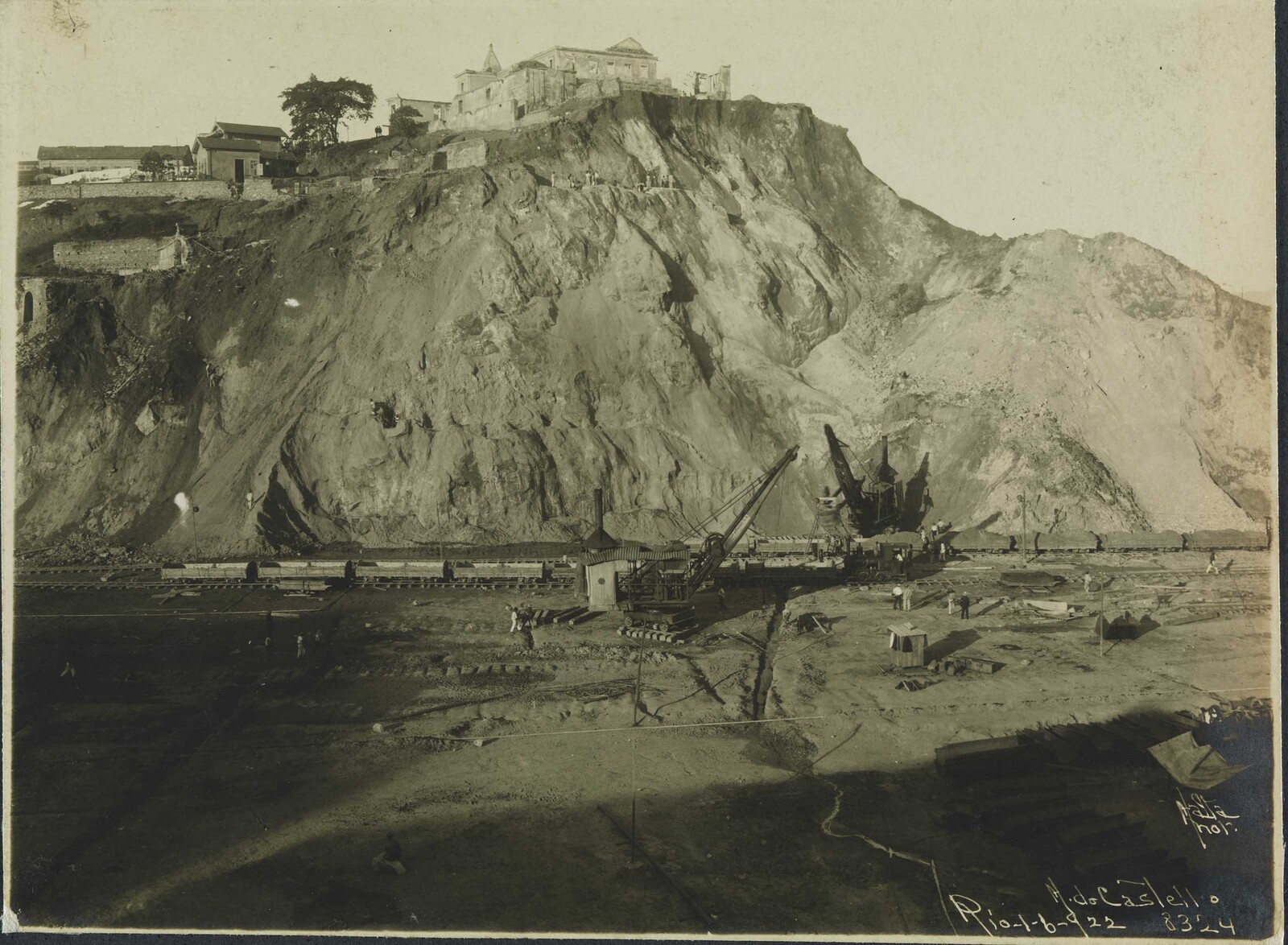

The geography of Central America, with its relatively short distance between the world’s two largest oceans and abundance of rivers and lakes, made the amphibious transport of goods across the Isthmus of Panama a viable industry throughout the colonial period. In the nineteenth century, entrepreneurs, explorers, and engineers began to propose numerous plans and designs for canal to connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans in Nicaragua and Panama.5 Chief among them was the French project undertaken by the Compagnie Universelle du Canal Interoceanique, which began work in 1879 under Ferdinand de Lesseps, who had previously completed the Suez Canal in 1869. Although the sea-level canal succeeded in Egypt, it failed in Panama, due in large part to its mountainous topography, as well as high death rates from yellow fever and malaria, which was popularly understood to be a serious threat to any renewed imperial efforts.6

As part of the US Government, the ICC began building a canal in 1904 that would traverse the varied topography of the isthmus with a series of locks. This would allow ships to move upward in elevation until they reached man-made Lake Gatún, which was created during construction by damming adjacent rivers. In light of the French failure, efforts to curb yellow fever and malaria began promptly with the creation of twenty-five sanitary districts corresponding to existing cities, including the larger terminal port cities of Panama and Colón; smaller towns along the proposed canal route, like Ancón and Gorgona; and work camps near major canal excavation, like Culebra.7 The kind of sanitary work varied considerably between the port cites, inland towns, and work camps.

An anti-mosquito brigade directed by William C. Gorgas in US-occupied Cuba, c. 1903. Source: William Crawford Gorgas, Sanitation in Panama (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1915).

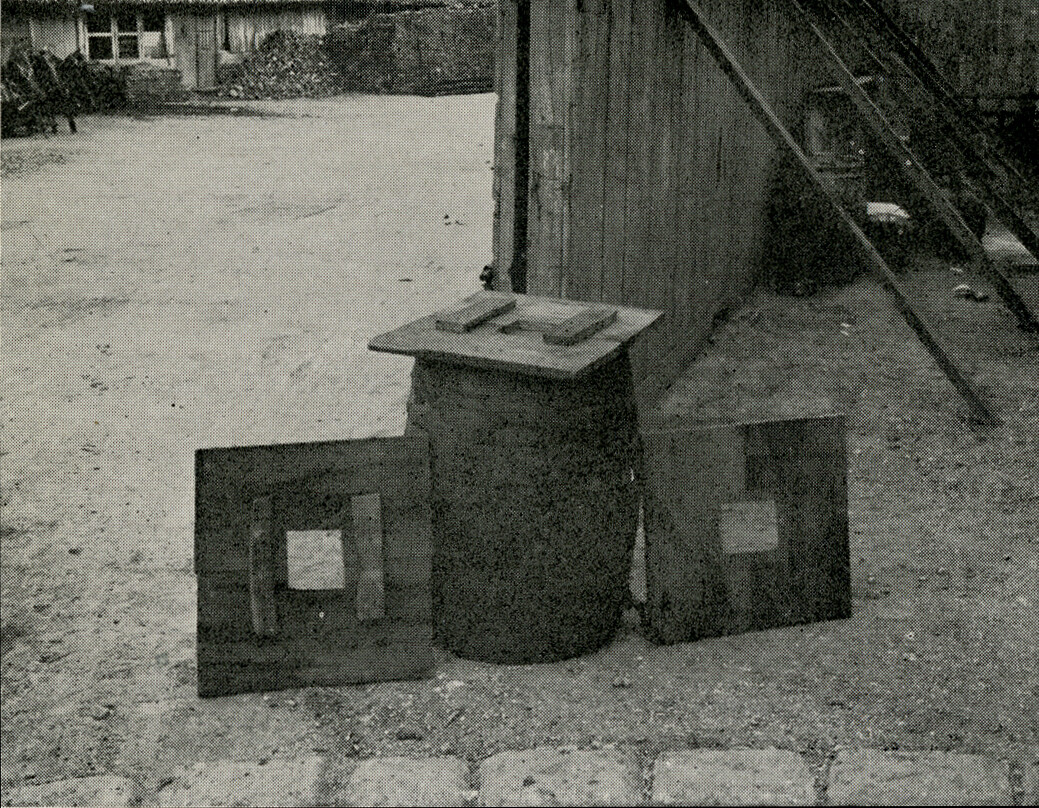

Covered barrels as required by new sanitary measures directed by William C. Gorgas in US-occupied Cuba, c. 1903. Source: William Crawford Gorgas, Sanitation in Panama (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1915).

An anti-mosquito brigade directed by William C. Gorgas in US-occupied Cuba, c. 1903. Source: William Crawford Gorgas, Sanitation in Panama (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1915).

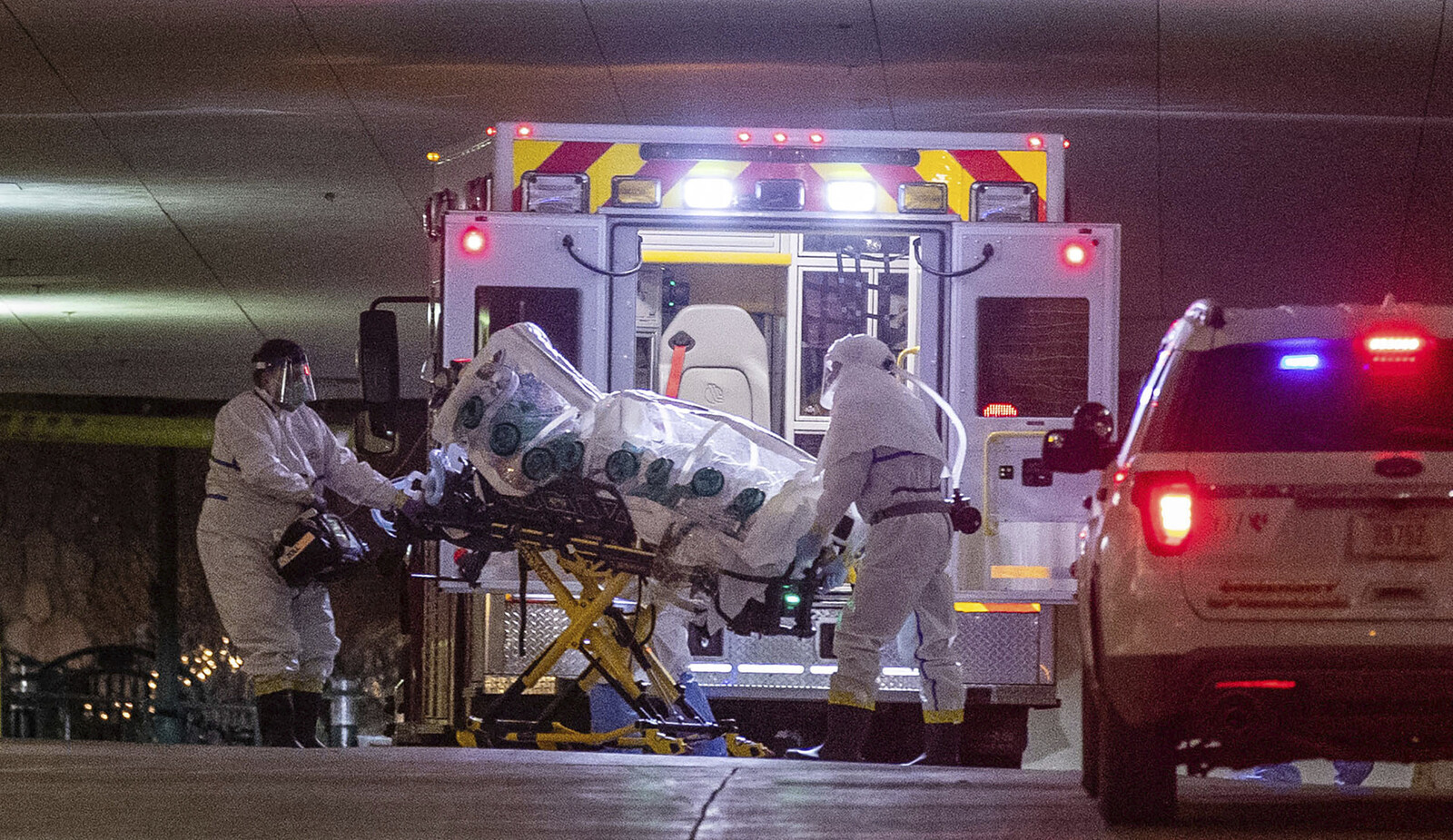

When Gorgas arrived in Panama in 1904, he brought more than knowledge of anti-mosquito techniques. He arrived with an anxious determination, due to the huge loss of life he had recently experienced in Cuba due to disease. In his last two months in the east of the island, the Army surgeon estimated that his troops had “a constant sick rate of over six hundred per thousand,” almost entirely due to yellow fever.8 The end of the French effort and the beginning of the US canal construction came on the heels of a trio of discoveries related to the transmission of malaria in 1897. Research performed in colonial contexts from British India to US-occupied Cuba debunked the long-held miasma theory that malaria was the product of the bad air (mal’aria in Italian). Thus, right as the US began to plan the construction of the canal, Gorgas understood that his sanitation work had a clear target and enemy: the mosquito.9 Assuming that canal workers would experience a similar sick rate to the US soldiers that occupied Cuba during the Spanish-American War, Gorgas estimated that in ten years in Panama, measures taken against yellow fever saved no less than thirty-nine million days of sickness for the entire labor force, or $39,420,000.10 Gorgas and others saw sanitation work as indistinguishable from the military occupation in Cuba and the success of the canal construction in Panama.

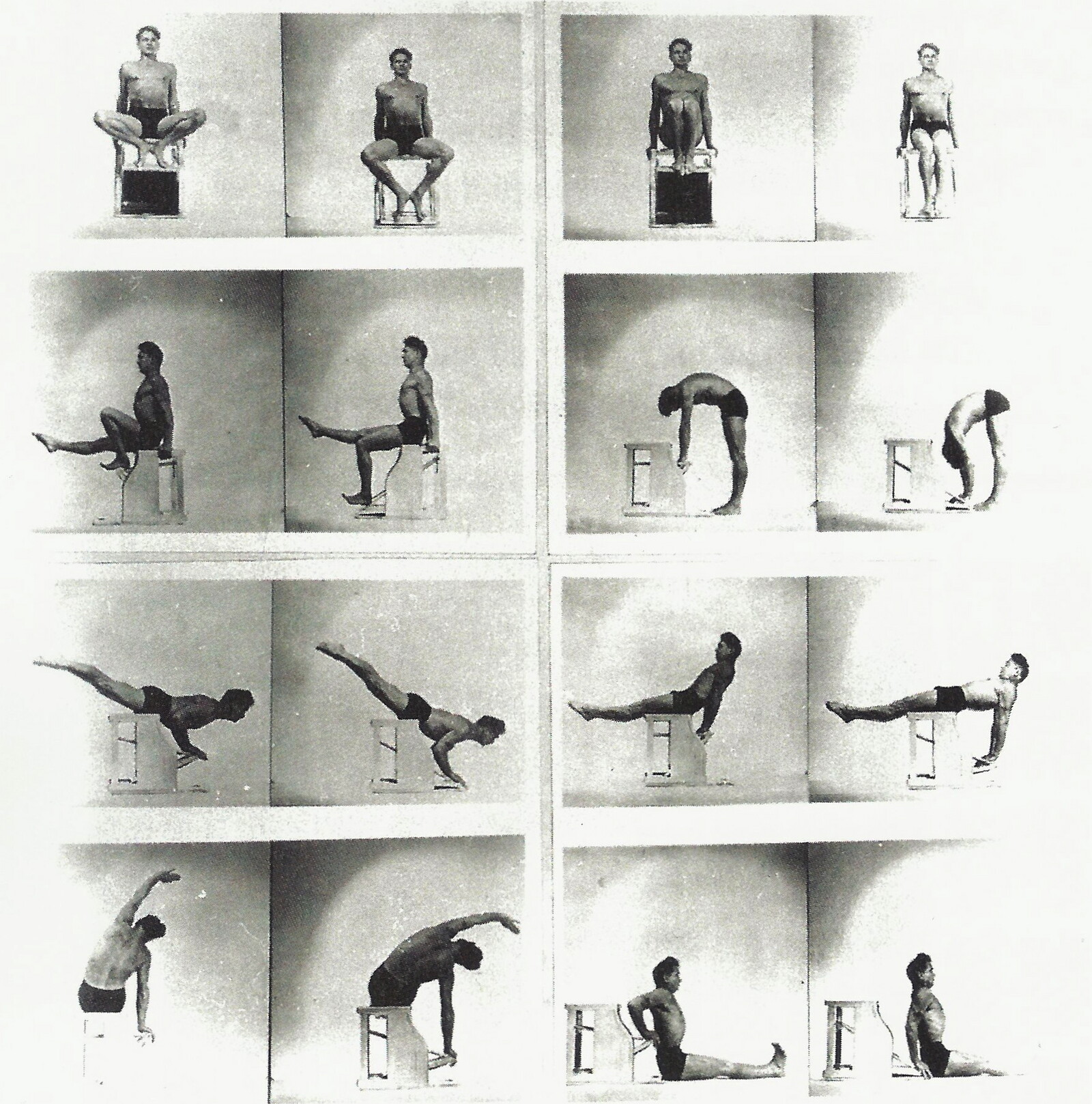

A mosquito brigade in Panama displaying the tools of sanitary inspection, fumigation, and oil spraying. Ladders in hand, the group of men stand next to the underground water pipes that would be installed to improve the removal of waste water, n.d. Source: Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering & Technology, Kansas City, Missouri, USA.

Gorgas’s sanitary efforts involved different strategies for different geographies and diseases, as yellow fever primarily affects urbanized, tropical areas and malaria tends to affect more rural areas.11 Short-term yellow fever eradication was a relatively attainable goal in small cities like Panama City and Colón, but the measures taken were extreme. In 1904 and in Panama City alone, a city of 20,000 inhabitants, Gorgas’s team used 120 tons of insect powder—the entire annual supply of the United States.12 Spraying was largely carried out by mosquito brigades, which checked households for compliance with new, mandated sanitary measures as well as checking for sick people to be quarantined and making repairs or modifications to the existing urban housing stock. But given that many locals were not only indifferent to the new imperial authority’s demands but resistant to yellow fever itself, these brigades also policed the activity of local residents.13

If the first sanitary measure undertaken by Gorgas focused on yellow fever in the coastal, port cities, the second and more protracted battle was with malaria, a disease caused by parasites that were widespread among the mosquito populations in the hilly forests of the Darien region. This effort quickly became inseparable from broader efforts to manage and divide the diverse labor force needed to construct the canal. The excavation and other building activities of the canal took place along the railroad lines that snaked across the isthmus connecting Panamanian towns, rural settlements, and a constantly shifting set of work camps. Although indentured Chinese laborers had been used in US railroad construction, officials were aware of the dubious optics of the coup and acquisition of the Canal Zone. This made them reluctant to use indentured labor for fear of public outcry in a post-emancipation environment.14 But because of the scale and speed of the US project, a massive labor force was needed.

Old boxcar bodies used as barracks, 1910. Source: Panama Canal Museum Collection (University of Florida), Seminole, Florida, USA.

There was much debate not only about who to enlist to build the canal, but also how to prevent organized resistance and revolt among them. As one official testified to the US congress in 1906, “there must be on the Isthmus a surplusage of labor. Otherwise, we will have interminable strikes.”15 That is, by ensuring there were always more workers than available work, the ICC could make labor scarce, keeping a pool of eager wage-earners and potential strike breakers if needed. Furthermore, rather than one vulnerable workforce, Chief Engineer John Stevens believed that having several different nationalities and ethnicities would be easier to divide and create competition, compelling them to work harder.16 In order to do this, the ICC created a segregated, dual payment system: the gold and silver rolls.

While the system had many exceptions due to the realities and challenges of getting consistent work for all the positions needed, white workers from the US were mostly hired for skilled positions and received payment in gold. These “gold-roll” employees could spend leisure time in segregated clubs and spend their earnings at special commissaries. Paid less and in silver—a less valuable metal—“silver-roll” employees were marked with an inferior status and limited access to Canal Zone amenities. West Indians and Black workers from the United States were mostly assigned to the silver roll. European laborers like Spaniards and Italians occupied a liminal racial category at the time, with some attaining gold-roll status, but most were also on the silver roll. As a system of segregated payment, commissaries, and housing, the gold- and silver-roll system constituted an apartheid society, a perverse reincarnation of the contemporary Jim Crow system that was in full effect at the time in the United States.17

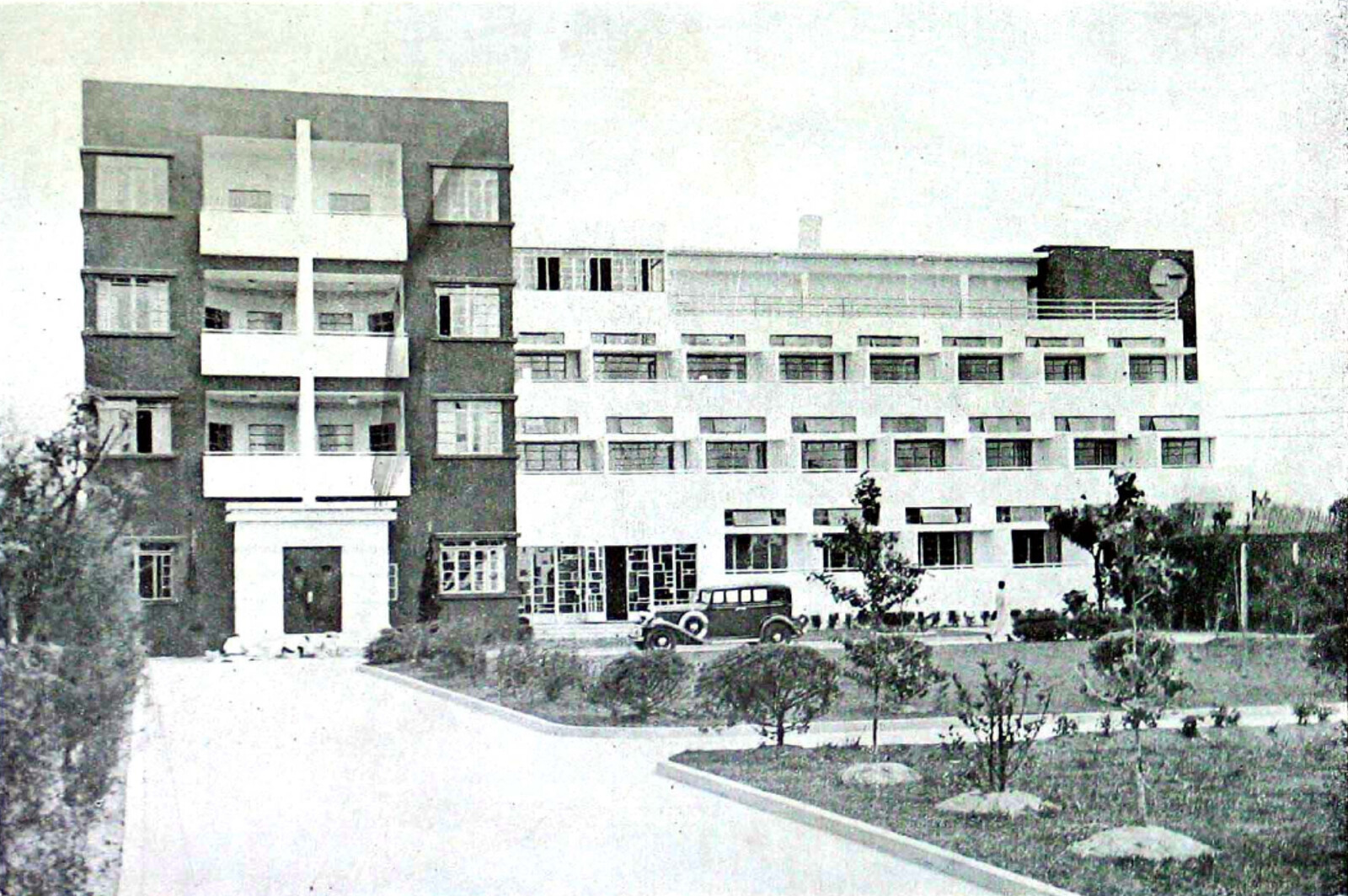

Typologies of Segregation and Separation

From the very beginning, the ICC, the US Government under Roosevelt, and the canal construction project faced constant critique within the US Congress, from the general public, and by journalists.18 While accusations of graft were perhaps the most common, suggestions of inefficient construction efforts and worker mistreatment—often connected to sickness—were leveled by progressive reformers.19 Although the ICC offered free housing to all its gold-roll employees, silver-roll employees paid rent.20 The quality of these accommodations, especially at the start of the project, was the subject of prominent criticism.21 Gold- and silver-roll employees were also provided separate and unequal housing: in the early years, many silver-roll laborers lived in tents completely open to the elements. As late as 1910, Galician workers on the silver roll were still living in boxcars ventilated only by a few small punched openings. Black laborers, also paid in silver, lived in conditions that “ranged from difficult to appalling.”22 When West Indians requested basic amenities like blankets and shelter to keep their clothes from being soaked in the rain, the US government responded that they didn’t even need sheds.23 Thus, ICC housing ranged considerably, from tents and boxcars to barracks and a wide range of mosquito-proof housing.

When it came to the mostly white, North American gold-roll employees, improved housing was cause for publicity. On December 11, 1907, three years after construction began, the Canal Record featured an article by Parker O. Wright, Jr., the Supervising Architect for the ICC’s Department of Buildings who was in charge of the design and construction of worker and staff housing, mess halls, hospitals, offices, social spaces, and industrial buildings for the canal project. His article, which would have been available to read in the Record, a publication distributed for free to gold-roll employees and sold to silver-roll employees, announced the creation of twenty-four new housing types for gold-roll employees of the ICC. He reassures readers that new housing can “meet all the requirements of necessity and comfort in a tropical, insect infested country,” describing his new designs as rational solutions to the problem of providing decent accommodations while keeping out mosquitoes.24 Advertising the creation of “the American type” in tropical Panama, Wright’s designs can be understood as part of an ongoing project of linking “types” and “typology” to national identity and race.25

Although abundant passive air ventilation and insect screens are widespread in warm climates today, extensive screened building exteriors were not common amenities in Panama before the beginning of the twentieth century.26 According to Wright, the design of new housing types was driven by cost, mosquito-proofing, and suitability for the different ranks of ICC workers.27 For white workers on the gold roll, he developed designs that ranged from single-family homes for married couples featuring wraparound porches on all sides, to more compact eight-bedroom quarters for bachelors. The amount of screened space provided was proportional to the ICC employees’ ranks. For example, Type 13 not only features a wraparound screened porch as a circulation space, but also a prominent band of empty space surrounding the enclosed bedrooms and living rooms at the houses’ interiors. For Black employees on the silver roll, Wright designed “Standard 1 Colored Barracks,” which features minimal screen space and one large, undifferentiated interior. Emphasizing the ability of screens to ventilate low-cost worker housing, Wright writes:

These barracks are provided to accommodate 40 to 80 men, allowing an average of 560 cubic feet of air per man. In case it should become necessary to increase the number of men, there is always a sufficient supply of air on account of the circulation provided by the openings at the top of the walls, the end verandas, no matter what the crowding might be, the air could not become foul.28

Thus, housing types for gold-roll employees and standard barracks for non-white silver-roll laborers used screens in different ways. For the former, they structured a large band of protective space in the verandas, which served as an attractive amenity. For the latter, however, screens allowed the ICC to maximize the number of people crammed into the barracks, armoring the agency against any complaints of crowding silver-roll employees by providing ventilation to an undifferentiated, generic interior.

The houses for gold-roll employees also used insect screens to structure interactions between them and their domestic servants. Wright explains that the possibility of mosquitoes to enter the houses has been reduced by minimizing the number of doors through the screened exterior, and to ensure that doors from kitchens or servant quarters never lead directly to the exterior. “In general, all screening should be so arranged that it will present the least temptation to servants or other careless persons to leave open the doors or windows, and the least opportunity to the ever-watchful mosquito to make its entry,” he writes in the Record.29 And in describing housing designed for silver-roll employees, Wright states: “Special consideration has also been given to the sanitary features of these buildings as well as to the location of them, also to methods of protecting the mosquito screening, the doors and windows, against careless and especially against willful injury.”30

The distinctions associated with the categorical, systematic definition of different domestic architecture for different classes of people follows a history of typology in architecture and criminology that was closely associated with scientific racism, social Darwinism, and the quest to categorize and rank people and buildings according to race.31 This is evident in Wight’s designs, and in particular the design of dining areas. For example, Type 13, a house designed for married gold-roll employees with families, came supplied with a kitchen, bedroom furniture, a fully equipped dining room, and storage space. In addition, it featured “a mosquito bar,” an area designated for the concoction and serving of anti-malaria tonics with quinine and gin (or perhaps just gin).32 No such conveniences were provided for silver-roll employees. Galicians eventually moved out of box cars, receiving standard barracks and a free-standing dining hall that allowed communal eating, and West Indians received some segregated barracks, but were served their food from an open-air counter.33 Worst off were convicts, most Black, who were relegated to a fenced-off corral with abysmal food and shelter, and forced to build roads and dig ditches without pay.34

The vast difference in the quality of housing was often explained and justified in terms of an incorrect correlation between race and disease immunity. George W. Goethals, who took over as Chief Engineer of the project from Stevens in 1907, responded to requests for mosquito nets and screens for West Indians by repeating a common and racist misunderstanding: “It is generally admitted … [t]hat the colored people are immune.”35 Yet in 1912, “as many as two-thirds of all West Indians reported sick or required medical attention … [m]ost of them catching malaria several times and confronting injury more than once.”36 By concentrating their anti-malarial efforts on gold-roll employee dwellings, US government officials allowed disease to spread.37

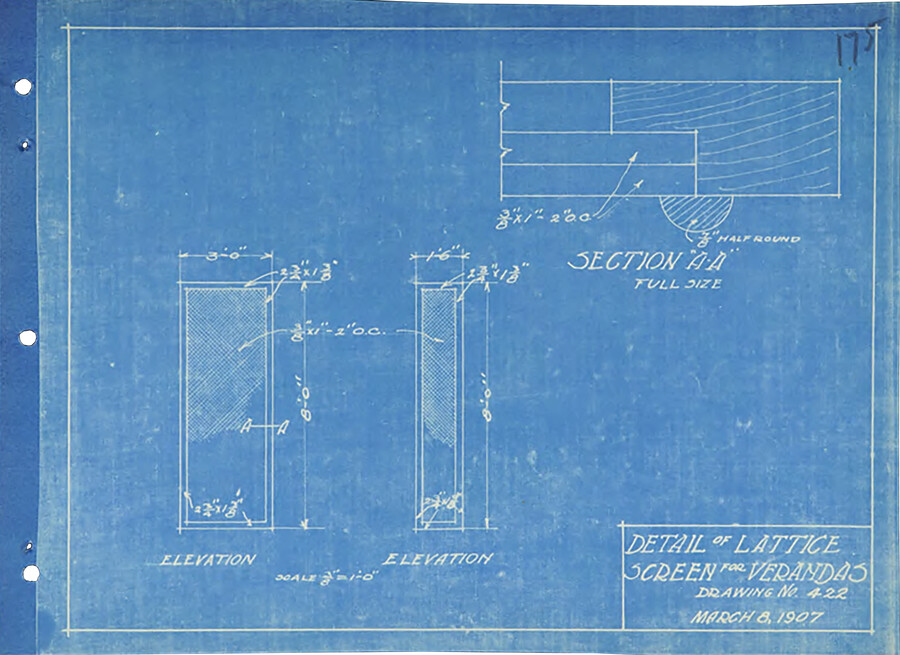

Parker O. Wright, Jr., detail of ICC screens, c. 1907. Source: Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering & Technology, Kansas City, Missouri, USA.

Rendering Nature Tropical

During the construction of the Panama Canal, work carried out by Gorgas’s sanitation teams paralleled (and often misinterpreted) research by entomological workers who were also stationed in the new US Canal Zone. While studying insects like mosquitoes, these scientists discovered a landscape that was highly influenced by human activity. That is, as rivers were dammed to create the canal, engineers were unwittingly expanding and improving the habitats for mosquitoes faster than concurrent sanitary efforts could counteract these environmental transformations.38 The use of the screen, a porous material, not only brought the design of low-cost housing in line with some of this epidemiological research, but calibrated the entire building skin to the scale of this science. Wright also took into account the interaction between different metal alloys and the humid air. His designs specified the wire used for the screening as No. 18 mesh—its opening size calibrated to the millimeter to prevent the passage of the anopheles mosquito—and its standard wire gauge comprised of at least 95% bronze or brass, to prevent corrosion in the humid air of the Darien region of Panama.

Similar attention is depicted in popular engineering handbooks disseminated in the decades following the Panama Canal’s completion, like Henry Home’s The Engineer and the Prevention of Malaria. Geared towards industrialists and businessowners to explain the science of malaria control, the author and civil engineer scrutinizes enlarged photos of the warp, weft, and hole count of cotton netting to determine how to specify and approve the correct fabric for preventing mosquito intrusion.39 Home also provides detailed information on the percentage of ferrous metals in copper alloys and the correct method for calculating wire gauge and mesh density for mosquito screens.40 Stressing the importance of this technical information, he offers a familiar reference, arguing that this work has proven its economic value:

In the case of the Panama Canal, anti-malarial works are said to have cost 5.5 percent of the cost of construction, and without this expenditure it is improbable that the large body of white and black labor employed on the canal could have been kept together.41

If Home believed screens and other anti-malarial work helped control an otherwise unmanageable workforce, prevailing views on race also structured the very use of these anti-malarial tactics. Just as entomological workers realized that the canal construction project was itself exacerbating disease, the provisioning of mosquito protection protected white workers than everyone else. Structured by prejudice, anti-mosquito architecture allowed malaria to continue spreading while reinforcing racial hierarchies.

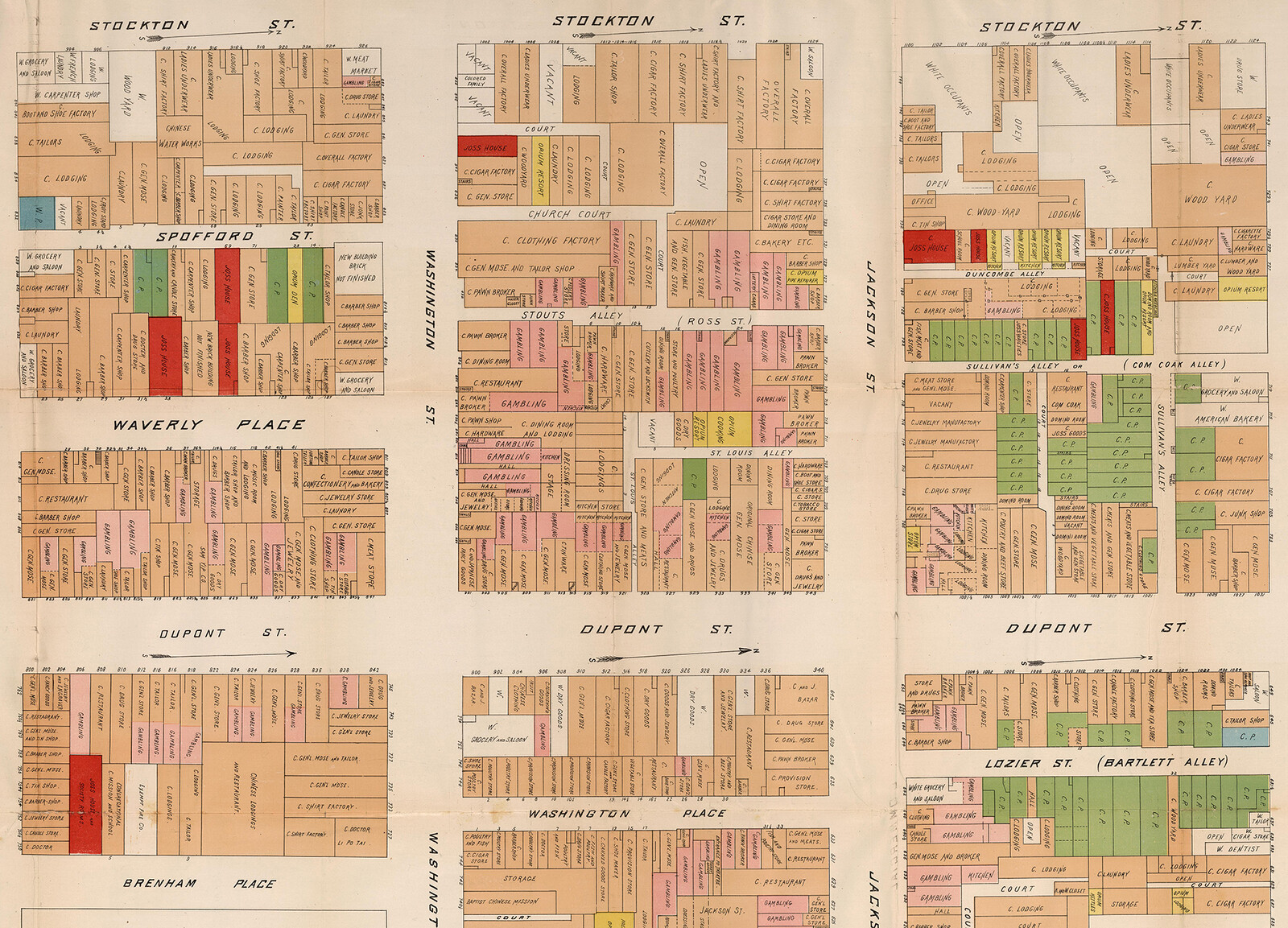

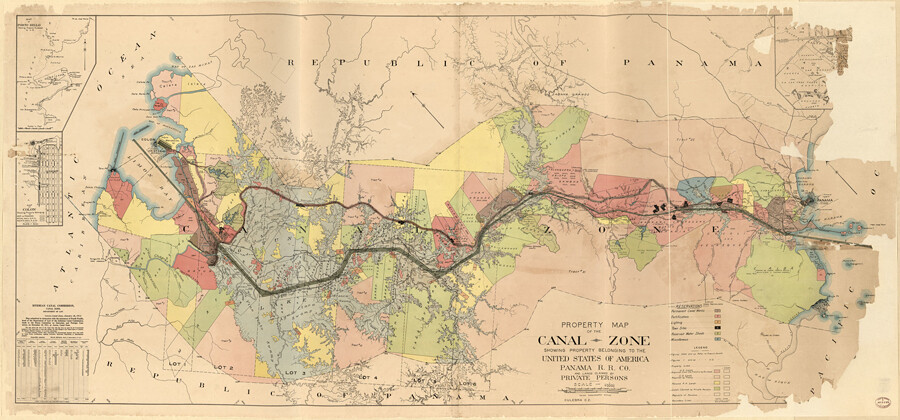

Isthmian Canal Commission, Property map of the Canal Zone showing property belonging to the United States of America, Panama R. R. Co., and lands claimed by private persons, 1912. Source: United States Library of Congress.

The fact that different types of housing reinforced ethnic and racial divisions cannot be separated from US imperial concepts about the tropics as a place. As David Arnold has argued, disease was associated with “a deep sense of alienation and danger,” and “was thus one of the defining characteristics of the tropics well before the 1890s, one of the factors that divided the civilized, temperate North from the heat, humidity and backwardness of the tropics.”42 Similarly, for Nancy Stepan, “the ‘tropical’ came to constitute more than a geographical concept; it signified a place of radical otherness to the temperate world, with which it contrasted and which it helped to constitute.”43 Gorgas’s belief that sanitation work in Panama proved that “the white man can live and thrive in the tropics” contains the familiar assumption that the tropics are fundamentally distinct, a place unto itself that can only be made suitable for civilization through the effort of engineering and science.44

In using deep-screened verandas and roof ventilation to solve the problem of disease and heat, Wright and the ICC effectively adapted the mosquito houses, nets, and traps that were widely disseminated among entomological workers in colonial contexts at the time to the architectural scale. While these devices were often used to catch mosquitoes, the ICC types catch the inhabitants. But despite Gorgas’s posturing of a “return” to the tropics, President Taft began a policy of “depopulation” in 1912 that would begin after the completion of the canal, abandoning work camps and minimizing permanent settlement as much as possible.45 Throughout the Caribbean region at the beginning of the twentieth century, the use of screen and net-covered structures mediated the relationship between people and mosquitos, and between people of different races and social classes. The domestic types in the Canal Zone figured the tropical landscape as constantly dangerous, in need of a buffer zone of protection. While managing the laborers through their relationship to insects—and each other—this low-cost architecture was crucial in the broader effort to turn the Isthmus into an imperial outpost and render the landscape tropical.

The title of this essay comes from Nancy Stephan, “Imperialism and Sanitation.” In: The Cuba Reader: History, Culture, and Politics, eds. Aviva Chomsky, Barry Carr, Alfredo Prieto, and Pamela Maria Smorkaloff (Chapel Hill: Duke University Press, 2019), 147. Frederic J. Haskin, The Panama Canal (Garden City: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1913), 105, my emphasis. Haskin was a prolific journalist in his day.

Tulio Halperin Donghi, Historia contemporánea de América Latina (Buenos Aires: Alianza Editorial, 2005; Originally published in Italian by Giulio Einaudi Editore, 1967), 298–299.

The US Canal Zone continued to be legally part of the United States until October 1, 1979. There is an extensive bibliography on conditions in the US territory. See Marixa Lasso, Erased: The Untold Story of the Panama Canal (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2019); Julie Greene, The Canal Builders: Making America’s Empire at the Panama Canal (New York: Penguin Press, 2009); and Michael L. Conniff, Black Labor on a White Canal: Panama, 1904-1981 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1985).

William Crawford Gorgas, Sanitation in Panama (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1915), 288–289.

Lasso, 17.

Alexander Missal, Seaway to the Future (Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2008), 23–24.

Missal, 26.

Gorgas, 279

For a discussion of the European context see Andrea Bagnato, “Microscopic Colonialism,” Positions (e-flux Architecture, December 2017), ➝.

A dollar a day for hospital care at that time. Gorgas, 281.

Paul S. Sutter, “‘The First Mountain to Be Removed’: Yellow Fever Control and the Construction of the Panama Canal,” Environmental History 21, no. 2 (April 2016): 253.

Gorgas, 151.

Ibid., 258.

Conniff, 25.

Greene, The Canal Builders, 48. See Hearings Before the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce of the House of Representatives, on the Isthmian Canal (Washington, DC, GPO, 1906), 33–35.

Greene, The Canal Builders, 47.

For an in-depth analysis of the racialized labor policies used during the construction of the canal, see Michael L. Conniff, Black Labor on a White Canal: Panama, 1904-1981 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1985), 31–36.

Labor conditions during construction of the canal itself were a constant source of criticism in the US press. Additionally, the conditions of worker housing were often discussed and derided in the newspapers of the day. See Edith Crouch, Architecture of the Panama Canal Zone: Civic and Residential Structures & Townsites (Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, Ltd.), 330.

Ibid., 191–225.

In addition, gold-roll employees paid no taxes, while silver-roll employees did. See Conniff, Black Labor on a White Canal, and Greene, The Canal Builders for more on the dual payment system of the gold and silver rolls.

The Panama Canal Retirement Association, The Canal Diggers in Panama 1904 to 1928 (Balboa Heights, Canal Zone, 1928), 9.

Conniff, 29.

Ibid.

Parker O. Wright, Jr., “What the French Did—Development of the American Type” Canal Record 1, no. 15 (December 11, 1907): 117.

Charles Davis has demonstrated that in early twentieth-century architectural discourse, prominent designers such as Louis Sullivan were also highly concerned with the relationship between architectural and national types. Charles L. Davis, Building Character: The Racial Politics of Modern Architectural Style (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2019), 167.

Photographs of the housing built by the French canal company show little to no use of screened windows.

Wright emphasizes materials and construction details had to be considered to suit the “official status of employees, the cheapest methods of construction, and an effective method of screening.” Wright, Jr., “What the French Did—Development of the American Type”: 117.

Ibid.

Parker O. Wright, Jr., “Screening of Houses” Canal Record 1, no. 19 (January 8, 1908): 147, my emphasis.

Parker O. Wright, Jr., “Buildings Erected for Laborers and ‘Silver’ Employees,” Canal Record 1, no. 17 (December 25, 1907): 134.

Georges Teyssot, A Topology of Everyday Constellations (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013), 69.

“Dwelling Houses in the Panama Canal Zone,” Carpentry and Building 30 (July, 1908): 234.

As Julie Greene argues, to “cover up this discrimination, malaria’s persistence was blamed on the West Indians’ presumed preference to live in the bush.” Missal, 61. On Strong and Fiske, see Walter LaFeber, The New Empire: An Interpretation of American Expansion, 1860-1898 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1967), 72–80, 99–100, and for a revisionist evaluation, Robert C. Bannister, Social Darwinism: Science and Myth in Anglo-American Social Thought (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2010), 228–229.

The arduous work involved in initial sanitary engineering efforts, which were inseparable from the creation of basic infrastructure of the Canal Zone, like clearing brush, cutting trees, leveling the ground, draining swamps and marshes, and filling ditches, was accomplished through the forced labor of convict gangs. Benjamin D. Weber, “The Strange Career of the Convict Clause: US Prison Imperialism in the Panamá Canal Zone,” International Labor and Working Class History, 96 (Fall 2019), 84.

Greene, 135

Ibid., 133.

Paul S. Sutter, “Nature’s Agents or Agents of Empire?: Entomological Workers and Environmental Change during the Construction of the Panama Canal,” Isis 98, no. 4 (2007), 750–751.

Ibid.

Henry Home, The Engineer and the Prevention of Malaria (London: Chapman & Hall, 1926), 136.

Ibid., 137–138.

Ibid., 3.

David Arnold, “The place of ‘the tropics’ in Western medical ideas since 1750,” Tropical Medicine and International Health 2, no. 4 (April 1997): 309.

Nancy Stepan, Picturing Tropical Nature (London: Reaktion, 2002), 17.

Gorgas, 289.

Lasso, 2.

Sick Architecture is a collaboration between Beatriz Colomina, e-flux Architecture, CIVA Brussels, and the Princeton University Ph.D. Program in the History and Theory of Architecture, with the support of the Rapid Response David A. Gardner ’69 Magic Grant from the Humanities Council and the Program in Media and Modernity at Princeton University.