The Edmondson railway ticket was invented in 1836, and entered general use on the British railways in the 1840s. Thomas Edmondson, a cabinetmaker and inventor, patented a machine that could produce a thousand serial-numbered tickets at a time, each 57 by 30.5 by .79 millimeters, from a larger sheet of cardboard. Edmondson’s machine placed the human hand at one remove from the cutting of the ticket, standardizing an emblem of modernized, accelerated movement. Countries linked to British industry in the latter half of the nineteenth century adopted his system. Argentina used Edmondson tickets, along with their patented production machines, from the 1870s until 1995, at which time they were made obsolete by paper tickets.

As historian Sarah Lloyd has observed, the ticket both predates and anticipates modernity. “Crucial,” she writes, “was the ticket’s potential to flow, to encapsulate and then release information, access, possession, or chance.” In eighteenth-century Britain, the handmade paper, metal, or bone ticket was ubiquitous in government services, church outreach, and entertainment; it was an object that “intensified and shaped social interactions.”1 For Lloyd, owing to their three-dimensional material presence, “they stood in for people and things; they materialized knowledge and experience; they pattered behavior and convention.”2 Early modern tickets also had a close relationship to money, functioning as IOUs since the “seaman’s ticket” that allowed the British military to defer wages during wartime. Distinctively thick and durable, Edmondson tickets became collectors’ items as countries retired them from service in the 1980s and 1990s.

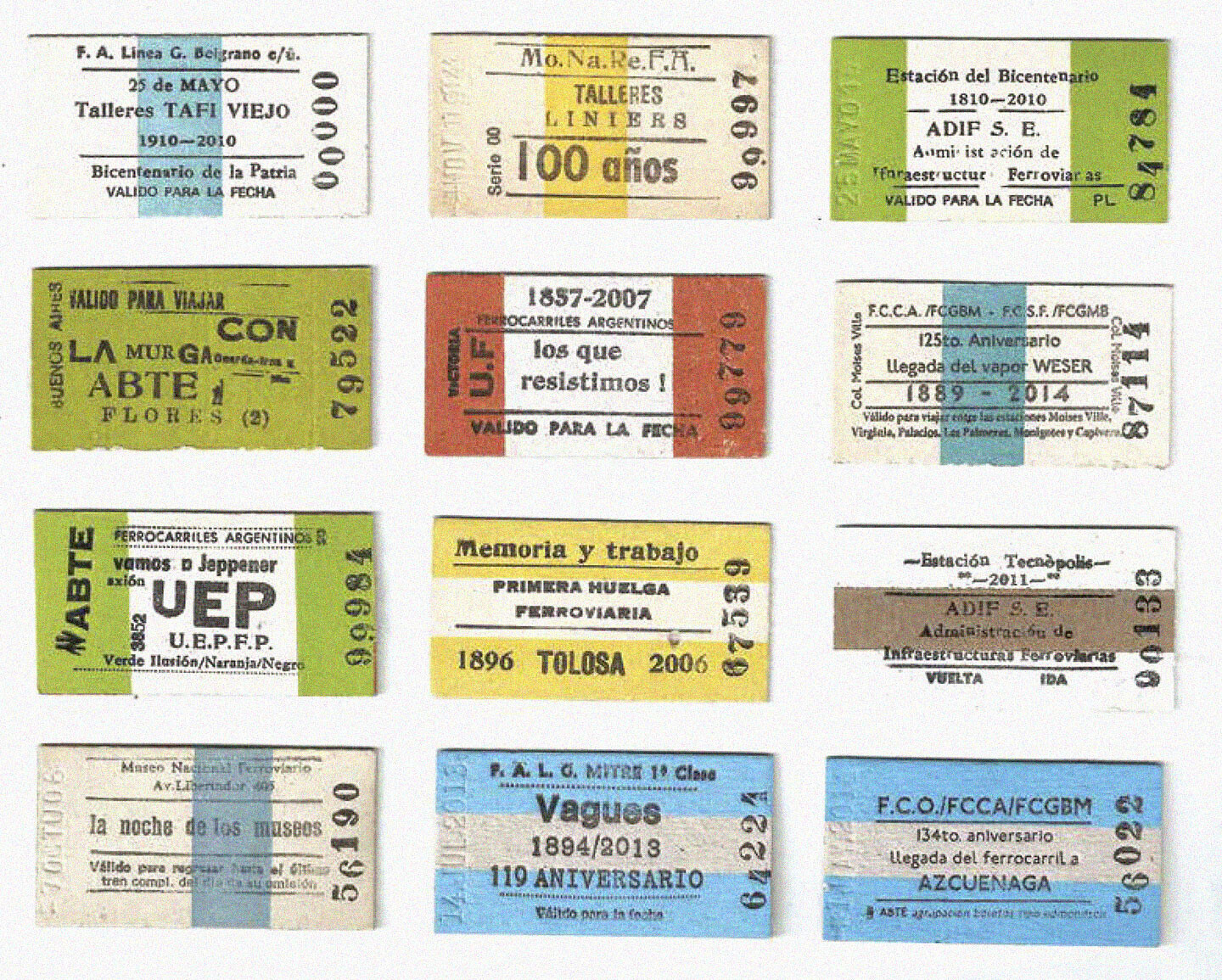

ABTE (Agrupación Boletos Tipo Edmondson), Custom Edmondson Railway Tickets, 1998-2013. Courtesy of Agrupación Boletos Tipo Edmondson.

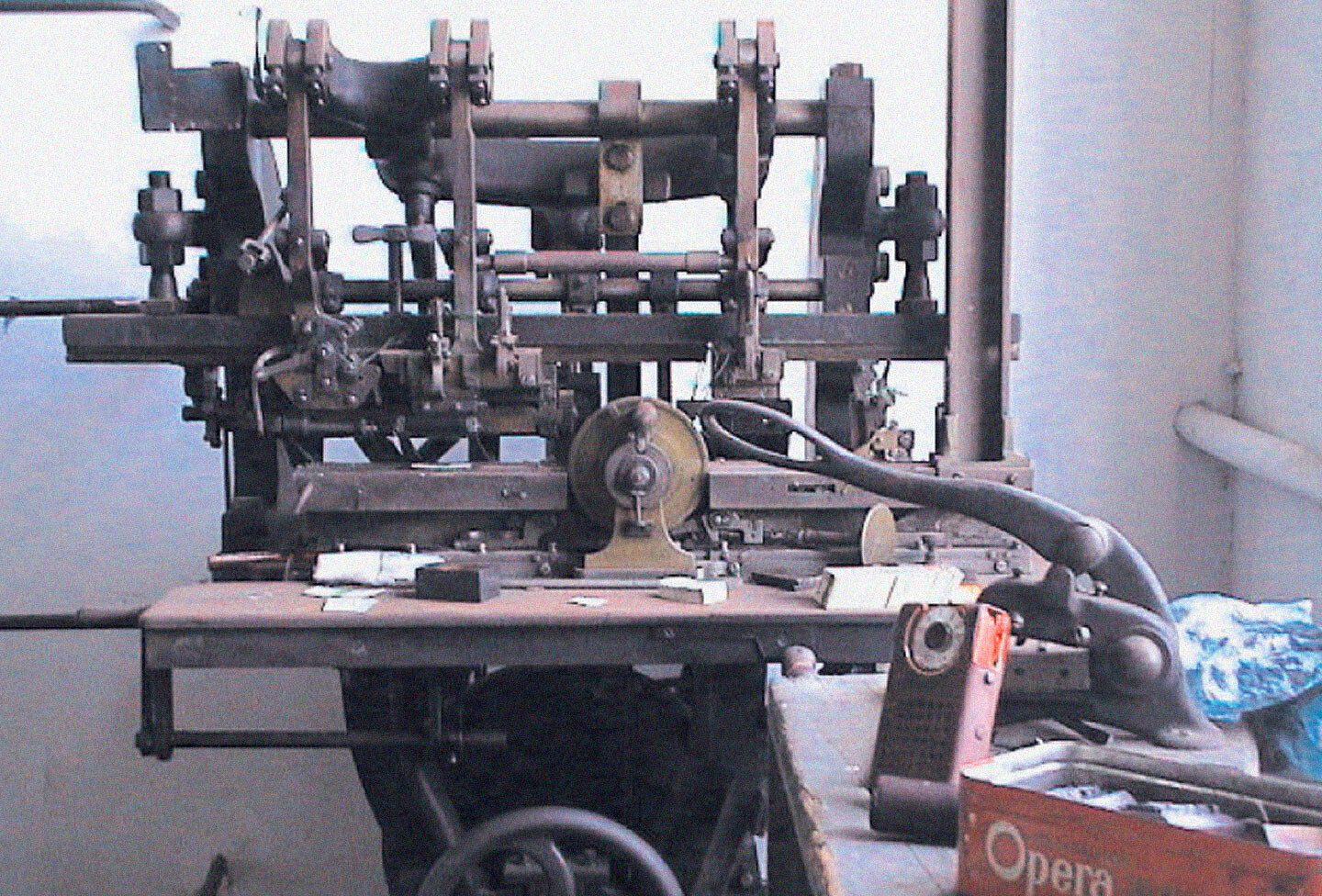

In 1998, artist Patricio Larrambebere founded Agrupación Boletos Tipo Edmondson (ABTE) with Javier Martínez Jacques, then a sociology student, as a self-described “quasi-fictional society” dedicated to the acquisition and preservation of Edmondson tickets and the material culture of the Argentinean railways more generally.3 Larrambebere remained ABTE’s most consistent member as others joined (Ezequiel Semo in 2003 and Javier Barrio, Martín Guerrero, Aldo Petrella, Gachi Rosati, and Alan Semo in 2012). In its initial period of activity between 1998 and 2005, ABTE united a network of Edmondson enthusiasts, exhibiting various ticket collections as installation art. The group was also able to rescue several antiquated ticket-printing machines from demolition.4 These were refurbished and reconfigured to produce new tickets with ABTE’s unique designs. In addition, the collective carried out interventions in train stations, such as their Cortes Pictóricos (Pictorial Cuts, 2002). The “cuts” consisted of the partial repainting and restoration of signs and walls of stations in and along former commuter rails of Buenos Aires (and more recently its provinces). Repainting only sections of these stations, with careful attention to the original paint colors and graphic design, had a striking effect: it revealed the degree to which the rest of the station was in disrepair. These actions drew inspiration from the Situationist International’s strategy of détournement: the “rerouting” of found elements in the urban environment, including transportation infrastructure, toward revolutionary ends. As the SI described it in 1958, détournement is “a method which reveals the wearing out and loss of importance of the old cultural spheres.”5 ABTE’s project, however, might be described as “rétournement”: the restoration, however partial, of places that have “worn out and lost importance.” This provisional “return” of neglected equipment or sites to their previous condition does not insure their return to wider use, but it does restore and insist upon their visibility.

The aging and obsolescence of Argentina’s railway patrimony in the 1990s was neither an inevitable nor a neutral process. It was the direct result of the privatization of the nationalized rail corporation Ferrocarriles Argentinos (FA), initiated in 1991 by Carlos Saúl Menem, president between 1989 and 1999. Initiated in response to Menem’s drastic transformations of Argentina’s economy and transportation system, ABTE’s conservation of the disappearing material culture of the railways was equal parts archival work and protest. Its use of outmoded printing and transportation technologies was not a symptom of scarcity in a Latin American country, but a reminder of a functional, state-run transportation infrastructure that was also a source of employment for thousands. ABTE aimed to activate the potential of railway patrimony for the present and the future, modeling confrontations with the past that intertwine research, collective action, and social advocacy.

This essay situates ABTE’s formation in economic and art-historical contexts, while also posing the question of what lessons could be drawn today from the group’s activities. ABTE received a retrospective at the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires in 2013, yet has rarely been addressed in the international field, despite the recent explosion of interest in Latin American modern and contemporary art, on the one hand, and the “global contemporary,” on the other.6 In reflecting on the group’s relative invisibility outside of Argentina, I hope to point to blind spots in our existing platforms and narratives for Latin American contemporary art, particularly when it comes to local frames of reference. Indeed, it is in the thoroughly local case that we might find parallels to other ravages of the neoliberal turn that David Harvey, among others, dates between 1978 and 1980.7 In this light, ABTE’s declaration that “railways are the future” is not triumphalist. Rather, it sounds a warning for other professions and geographical contexts, from laborers in increasingly postindustrial societies to the intellectual precariat.

Antique Edmondson ticket-printing machine, reclaimed prior to demolition by ABTE (Agrupación Boletos Tipo Edmondson). Courtesy of Agrupación Boletos Tipo Edmondson.

A Casualty of Crisis

Argentina was the world’s first developing economy to privatize its train services. The country’s railroads originally began as an national investment in 1855. Beginning in 1870, England invested in and gradually acquired them—as was the case with many railways throughout South America.8 By 1914, Argentina’s rail system was the tenth largest in the world, with a dense network of branches connecting Buenos Aires, a federalized capital from 1880, with the provinces. Between 1946 and 1948, President Juan Domingo Perón nationalized all six of the original train lines. His reclamation of this massive network for the country’s exclusive profit was one of his major achievements, and remained a symbol of Peronism’s alliance with the working class.9 In 1990, before privatization, Ferrocarriles Argentinos boasted thirty thousand kilometers of rail tracks. It was the largest railroad in Latin America, and the sixth largest worldwide, with assets totaling $8 billion ($16 billion adjusted for 2019), making it one of the largest corporations in the country. It was “vertically integrated, with in-house units for construction, maintenance, operations, marketing, and real estate, as well as horizontally integrated, offering freight transport, intercity passenger transport, and suburban passenger transport in BA (i.e. commuter rail service),” according to a 1997 World Development report.10 FA also had a powerful union that could, and periodically did, bring the country to a halt with strike actions.

Menem entered office in the midst of a hyperinflation crisis resulting from the reckless financial policies of the Proceso de Reorganización Nacional (Process of National Reorganization), the economic and repressive measures put in place by the dictatorship that ruled Argentina between 1976 and 1983. Under the junta, President Jorge Rafael Videla worked with his economy minister, José Alfredo Martínez de Hoz, a follower of Milton Friedman and the Chicago School of Economics, to radically open the Argentinean economy to investment, while exploding national debt through Wall Street and International Monetary Fund loans. With the tablita cambiaria (currency exchange board) in 1978, Martínez de Hoz overvalued the peso at the expense of the country’s national debt—a predecessor of Menem’s 1990 “pegging” of the peso to the dollar. The temporarily strong currency became known as plata dulce (sweet money), due to its purchasing power abroad.11 In February 1981, an unavoidable devaluation sent the peso plummeting, Martínez de Hoz into retirement, and Argentina into the ranks of Latin American countries trapped in what has since become known as the “lost decade” of IMF-mandated austerity measures.12 In December 1983, the country transitioned to democracy with an external debt of $46 billion, nearly 80 percent of its GDP.13 President Raúl Alfonsín attempted to ameliorate this damage during his five years in power through a range of short-term strategies; for example, he initially suspended payments to the IMF so that funds could be directed toward public services. Inflation rates continued to increase, however, and by early 1985, with the rate at 626 percent, the country was held in violation of IMF austerity targets, meaning that it could receive no further loans. Economy minister Bernardo Grinspun was fired, and his successor Juan Vital Sourrouille initiated a currency shift from the peso to the “austral” on June 15, 1985. From its introduction, the austral rapidly decreased in value until 1989, when a thousand-austral bill was worth seventy dollars; the currency was retired from circulation on December 31, 1991.14 In 1988, Alfonsín lowered wage increases to 4 percent after salaries had already diminished by 42.7 percent during the first five post-dictatorship years. The Confederación General del Trabajo, the country’s oldest and largest union, organized a series of strikes in response.

Menem, a Peronist, took over on July 8, 1989 with consumer prices having risen 3610 percent from the past year.15 He passed the Ley de Reforma del Estado (Law to Reform the State Sector) on August 17, 1989. This law paved the way for the privatization of myriad government-owned services over the course of the 1990s, including mail, telecommunications, oil, gas, electricity, water, airlines, and the railways.16 He also pardoned thirty-nine key figures of the dictatorship, including military presidents Videla, Leopoldo Galtieri, and Roberto Viola. According to Vicente Palermo, Menemismo’s shift to “policies one can classify as productivist rather than distributionary” spelled “the end of Peronism as a populist movement” (although this association was arguably restored during the Kirchner era).17 Economists had designated Ferrocarriles Argentinos an SOE, or major “state-owned enterprise,” which left it particularly vulnerable to privatization.18 By 1993, FA was a decimated version of its former self, with 1 percent of its previous employees. Because of the destructive effects on both railway workers and the railways themselves, Juan Carlos Cena describes the privatization process as “el ferrocidio”—a kind of assassination.19 FA employees who lost their jobs received one month’s salary for each year of service, with no maximum. The average worker had spent twenty years in service, and cost the government approximately $10,000 per worker—sums paid out, unprecedentedly, by the World Bank. Menem divided the vast railway network into sectors, to be managed separately by different companies, drastically reducing service outside metropolitan centers.

The Argentinean economy began a precipitous decline in 1998, shrinking 28 percent by 2002 due to the peso’s inevitable devaluation. In November 2001, in advance of the IMF suspending its next loan, there was a run on banks, leading to the “corralito” of December 2, which froze all bank accounts for twelve months and allowed only minute weekly withdrawals. Between December 19 and 21, 2001, a broad section of the public took to the streets to protest. Menem’s successor, Fernando de la Rúa, promptly resigned, fleeing the Casa Rosada in a helicopter; some thirty-nine people were ultimately killed by police and security forces. The historic depression technically lasted until 2002, but its aftereffects are still felt today in continuing economic instability.20

-97WEB.jpg,1600)

-97WEB.jpg,1200)

Patricio Larrambebere, La Paternal (FCGSM), 1996. Acrylic on canvas. Courtesy of the artist.

From Representation to Intervention

Patricio Larrambebere began collecting vintage Edmondson tickets in 1993, while still working as a representational painter. His cityscapes of working-class neighborhoods and rail yards in Buenos Aires Province often featured portraits of friends in the foreground, as in Ciro y Miki en Remedios de Escalada (1993). María Guillermina Fressoli regards this dimension of personal recollection as a continuing thread throughout Larrambebere’s work that sometimes conflicts with that of collective memory.21 In 1996, he abandoned the figure in favor of visual imagery of rail yards and stations, their platforms, and signage. His line became more precise, recalling Charles Sheeler’s Precisionism as well as the austere graphic novels of Chris Ware in the late 1980s and 1990s. In a series of paintings of signage from different rail stations, Larrambebere selected examples from all six of the different original lines nationalized by Perón: Liniers (FCDFS) (1996) corresponds to the Domingo Faustino Sarmiento line, which was almost completely halted after privatization. La Paternal (FCGSM) (1996) was of the General José de San Martín line, which went from Retiro Station to points west. In the painting, a line of multicolored, ambiguous protrusions peek over the wall, where FA’s logo is visible on a railcar. They suggest picket signs, a protest hidden from view. Doctor Antonio Saenz (FCGB) (1997) is of Ferrocarril General Belgrano, the most extensive rail network in Argentina, which at one time connected Tucumán to Córdoba and extended all the way to Bolivia. The station sign for Victoria (FCGBM) (1997), on the General Bartolomé Mitre line, hovers ambiguously, both a believable detail of an actual site and an ironic invocation of the spurious “victory” of privatization. An advertisement below the platform promises “freedom of economic action and unlimited rides when you obtain an abono,” the multi-ride passes that replaced Edmondsons. To its right, a fragment of another advertisement reads “Menos que Cero,” a reference to a Buenos Aires rock band for which Larrambebere once designed a record cover. The group’s name derives from the 1977 Elvis Costello song “Less Than Zero,” a condemnation of British fascist Oswald Mosley’s attempt to whitewash his past in a 1975 television interview.

In its layered references and cool observations of changes in the urban and social fabric, Larrambebere’s early work reaches back further still, to the socially conscious beginnings of painterly modernism—Courbet, Manet, and Pissarro. There had been a tradition of Argentinian artists using representation as a form of political commentary. In the early 1960s, Grupo Nueva Figuración broke with the previous generation’s abstraction movements (from the concrete art of Arte Concreto-Invención and Grupo Madí to the informalist experiments of Arte Nuevo) by reintroducing the figure in collage and assemblage works that made reference to class stratification and political instability. In this period, the Peronist Party was kept off the ballot and the military overthrew two democratically elected presidents, in 1962 and 1966.22 During the Proceso de Reorganización Nacional (1976–83) a number of artists who practiced conceptualism in the late 1960s turned to neo-surrealist or hyperrealist painting to obliquely address state repression.23 Fressoli argues that Larrambebere’s paintings collapse the history of the Argentinean railways onto its present, producing a “tension” that amounts to a contemporary manifestation of “history painting.”24 In the 2000s, Larrambebere would similarly derive paintings from archives of visual and material culture related to Pan American World Airways, the Malvinas (Falklands) War, and Guyana, in addition to further railway paintings.25

Larrambebere’s concerns as an artist informed those of ABTE as a whole, and remain inextricable from those of the group. As first conceived with Martínez Jacques, the “society” of two reported on its activities and Edmondson collections in “Bolezines” that would fold to the dimensions of a single ticket. One of the artists’ inspirations was the 1968 album The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society, which similarly harks to then-disappearing modes of London life.26 Early interventions included 24 Reflexiones sobre Nuestro Presente Ferroviario (Twenty-Four Thoughts on our Contemporary Railways, 1999–2000), a series of stickers that adapted the font and graphics of Trenes de Buenos Aires, the private company that had acquired the Buenos Aires commuter rail. The stickers were affixed, guerrilla-style, to walls and objects in various stations. Their messages alternated between direct protests such as “La cultura no es eficiencia” (Culture is not efficiency) and wry witticisms, as in a sticker left on a long-dead station clock: “Los trenes andan a horario … y el reloj del anden?” (The trains run on time … and what does the clock run on?). A series of videos detailed the group’s actions as well as archival footage, from 1995, of the ticket-making machines used to produce some of the final Edmondsons in circulation. For Máquinas Expendedoras Humanas de Boletos (Human Ambulant Ticketing Machines), a project in two versions, the artists distributed Edmondson tickets in cyborg lucha libre masks on June 22, 2001, which was designated “Booking Clerk’s Day” (the anniversary of Edmondson’s death). The booking clerk was a particular focus of ABTE’s early interventions, given that at many of the different railway lines, this job—the human point of contact with the customer, the arbiter of who could enter the station and travel the line, and, of course, the distributor of tickets—was the only one that had not been significantly reduced. The Human Ambulant Ticketing Machine was a worker transformed into the machine designed to replace them, insisting on the recirculation of outmoded tickets. These interventions at stations were accompanied by gallery-based installations, as in the earliest, Ferrocarriles Argentinos, at the Museo Nacional Ferroviario in 1998, and Sede Temporario (Temporary Headquarters) for ABTE at Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires in 2002, the walls of which were constructed out of the larger sheets used to cut tickets. Other artists, including Eduardo Molinari, participated in organizing the many tickets on hand, both originals and ABTE’s new designs, into new configurations. Molinari had recently initiated his analogous Archivo Caminante (Walking Archive) project (2001–present), which combined meticulous research in national archives with photographs and objects sourced from walks around Buenos Aires.27

One of the first of ABTE’s restorations in 2001 consisted in repainting the decrepit Coghlan Station in its original yellow, in honor of its 110th anniversary. A performance complete with a sandwich man informed the public about the site’s history. New nameplates were added to the station to replace those removed in 1998 amidst the transfer to private ownership—the artists called this a “typographical action.” When, in 2005, Néstor Kirchner formed Unidad de Gestión Operativa Ferroviaria de Emergencia (UGOFE) to temporarily renationalize some of the worst-run railway lines, ABTE critiqued this half-measure by repainting several station signs only halfway, for the series los nomencladores mita y mita de UGOFE (the half-and-half UGOFE nameboards), some of which produced wordplays (for example, Caseros into CasEROS). Here, painting was displaced from the canvas to the physical features of the stations themselves—from representation to a kind of signaling device. It also shifted registers to a more quotidian sort of “painting,” that of refurbishment and maintenance—in other words, painting as labor (albeit unpaid in this case). Both Larrambebere and ABTE’s projects insisted on a place for painting in Argentinean contemporary art, but for ABTE the practice palpably shifted from the labor-of-art to art-as-labor. In the latter, this identification might be romantic or problematic were it not for the fact that it is better described as a haunting, a ghost-labor in the place of absent workers. This component of ABTE’s activities became more explicit when Ezequiel Semo joined in 2003 and the group expanded its research and incorporation of historical uniforms for interventions.

For the retrospective at the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires, Larrambebere summed up the group’s aim as the restoration of visibility to that which had been lost in the privatization of not only a material culture but specific modes of artisanal labor:

What was it that drew ABTE to the street, or, more precisely, the territory of the railways? It was a reaction to the shameless Tupac-Amaru-ization and subsequent concessioning of Ferrocarriles Argentinos in the mid-nineties … It began to appear in geography, facilities, in the state of the cars, in the stations: the absence of those who worked, and embodied, the railroad … We were losing all that had been ours. And in this desire to cling to that experience, we began to internalize the labor of those who now lacked their previously essential roles for the railways: the artisans …To restore the presence of the artisanal, taking up its tools and crafts, was a form of action amidst the degradation of our quotidian landscape.28

ABTE (Agrupación Boletos Tipo Edmondson), Mercedes, 2013. Railway intervention, January 6, 2013. Courtesy of Agrupación Boletos Tipo Edmondson.

Postcrisis: Nostalgia and Collectivity

Larrambebere emerged as an artist when one of the centers of the Argentinean art world was the Galería del Centro Cultural Ricardo Rojas at the Universidad de Buenos Aires, directed by Jorge Gumier Maier between 1989 and 1996.29 Some members of “Grupo Rojas,” such as Fabián Burgos and Graciela Hasper, returned to geometric abstraction, one of the early signature styles of Argentinean modernism in the late 1940s, but without the Marxist utopianism of their forbears. Others, such as Marcelo Pombo, embraced a ludic approach to the ready-made: garbage, antique objects, and the cheap new consumer goods that flooded the country after Menem’s pegging of the peso to the dollar were collaged on canvases or assembled into sculptures.30 Larrambebere’s interest in trains and overtly working-class imagery might be seen, on the one hand, as an outright rejection of Grupo Rojas’s signature irreverence (using an epithet with homophobic undertones, some critics dubbed the group “Arte Light”). Yet a closer look at Rojas artists such as Sebastián Gordín reveals a respectful fascination with the past that parallels Larrambebere and ABTE. Gordín’s Siete Cinemas (1995) depict since-demolished buildings from the Odeón film theater chain in miniature. The Buenos Aires version hosted Argentina’s first film screening in 1896, and was demolished in 1991 to make room for a parking lot.31 For Grupo Rojas, the debasement of new commodities and the lost glamour of the old added up to the same message—that a world was being lost amidst neoliberal transformation—at the heart of Larrambebere and ABTE’s work.

ABTE preceded and dovetailed with a larger set of artistic responses that art historian Andrea Giunta has designated poscrisis: “a period of recuperation with respect to the violence of the most frigid moment between late 2001 and all [of 2002].”32 These practices emphasized collective action, either in parallel or as direct assistance with other modes of political activism in Argentina during this period. “The studio setting was replaced by the street,” Giunta argues, “and for a time it seemed like the individual artist disappeared, immersed in so many groups. This produced, in a certain mode, a ‘collectivization’ of artistic practice.”33 Among many other examples, Taller Popular de Serigrafía (Diego Posadas, Mariela Scafati, and Magdalena Jitrik) helped to print T-shirts and posters for street-based protests and the occupation of factories. In 2003, the Eloisa Cartonera project (Javier Barilaro, Washington Cucurto, and Fernanda Laguna) was initiated in the working-class neighborhood of La Boca; the project drew on existing networks of cardboard trash collection to begin a publishing house that sold pirated copies of various books, yielding a newfound business opportunity for some of Buenos Aires’s poorest citizens. Demands for economic transparency dovetailed with continued efforts to fully open the books on the Proceso and prosecute its military architects; groups such as H.I.J.O.S. (formed 1995) and Grupo de Arte Callejero supported street actions to promote awareness of the disappeared and sites of forgotten state violence in the 1970s. Under Néstor Kirchner, these efforts bore fruit, with Menem’s pardons being lifted in in 2006 and Videla returning to prison, where he later died, in 2007. Grupo Etcétera (formed 1998, various members) carried out street-based “Escraches,” in which they mocked former military officers and Menem-era bureaucrats alike. With Operación BANG! (2005), the group renamed itself Fundación de la Internacional Errorista, mocking Bush-era “errors” in counterterrorism policy with a fake “invasion” of the beach at Mar del Plata on the occasion of the US president’s visit for the Summit of the Americas. Police mistook the performance for a real “insurgent” attack.

In their collective formations, postcrisis practices in Argentina paralleled larger changes in social movements towards self-organization, and horizontalidad, or horizontality. Marina Sirtin defines horizontality as “a form of direct decision making that rejects hierarchy and works as an ongoing process.”34 Horizontalism and self-organization imply modes of production that no longer depend on the government for help—although some such groups received funding from Néstor and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner’s successive administrations.35 ABTE adapted two horizontalist characteristics: leaderless organization and the performance of extra-governmental services. Yet ABTE’s labor was artistic precisely insofar as it was no longer necessary, existing in the breach between past and present. The group sidestepped a neoliberal reading of horizontalism as proof of the “resilience” of groups left to subsist without government support, which ironically justifies further reduction of state services.36 It also refuses any reading of “social practice” as proof that contemporary art might supplement development or services that a state could provide.

In 2012, a reconstituted and expanded version of ABTE began to refurbish increasingly remote, abandoned stations in the provinces of Buenos Aires, taking entire days and sharing asados at the sites. One station, Vagues, was converted into a “Center for Railway Interpretation,” with works donated by the artists—a museum for trains that will never arrive. As Javier Barrio’s recollection of the group’s 2012 repair of the Dr. Domingo Cabred station attests, these field trips could be perceptually disorienting:

When I went with ABTE to restore the sign to the Cabred station I had a paranormal experience. The eight-hour work day in which the poster was painted became a distorted trip. The chromatic contrast of the fresh paint against the deteriorated and twisted poster produced a strange sensation, as if we were making up a dead person … These days a hundred kilometers from the city were an act of will against this slow erasure that had lasted about forty years. The painting, whose slow evaporation by the action of the sun had faded the letters, the frame and the background of the poster, was restored within a period of eight hours. Sitting down to observe this process is almost a lysergic experience.37

ABTE’s post-2012 projects were not undertaken to protest a particular crisis or regime. Rather, they model history-work as a way of life—a mode of labor outside of late capital—lingering on in its destructive wake.

ABTE (Agrupación Boletos Tipo Edmondson), Alegre, 2013. Intervention in an Argentinian railway track, November 23-24, 2013. Courtesy of Agrupación Boletos Tipo Edmondson.

Value and Memory

By way of conclusion, we can return to the Edmondson train tickets, the initial material foundation of ABTE’s work of conservation and production. In the group’s installations, the Edmondson served as an irreducible unit with consistent features, akin to paper money or coins—yet with its value destabilized. Being out of circulation prior to the formation of the group, Edmondson tickets had instead become collectibles, their value ostensibly ranging from worthless to something well exceeding their original cost. By then making their own custom Edmondsons, ABTE added the open-ended exchange value of the artwork to the mix. When these original and newly produced Edmondsons were exhibited in sites where they formerly conferred access and transport, past, present and future were collaged atop one another, as in ABTE’s unpaid, unsolicited maintenance work. This is an expanded notion of collage—a “historical avant-garde” technique invoked by the appearance of forbears such as Kurt Schwitters on ABTE’s doctored Edmondsons. ABTE’s mode of collage, however, recontextualized artifacts as well as artifactual labor, lending them new uses. The tickets—and by extension the recovered ticket-making machines, the vintage uniforms and paraphernalia of railway patrimony, and most of all the fired workers in absentia—served to haunt the dire conditions and stations of 2001 and 2002. ABTE’s rétournement fought against both amnesia and any uncritical “return” to the material past. In this sense, ABTE corresponds to Svetlana Boym’s notion of “reflective” rather than “restorative” nostalgia: “Reflective nostalgia … can be ironic and humorous. It reveals that longing and critical thinking are not opposed to one another.” Restorative nostalgia, on the other hand, involves a kind of denial of the present, and the dead-serious belief that an unproblematic past can be fully recovered. “Any project of exact renovation,” Boym writes, “arouses dissatisfaction and suspicion; it flattens history and reduces the past to a façade, to quotations of historic styles. The work of memory resides elsewhere: ‘The renovated “old stones” become places for transit between the ghosts of the past and the imperatives of the present.’”38 Ultimately, ABTE’s reclamation of the obsolete unfolded with an eye toward the future. It was the group’s hope that heightened consciousness about what had happened to the Argentinean railways might lead to real policy changes, and reinvestment in the legitimate culture of work that FA had once facilitated.

“Los años K,” as the Kirchner years (2003–15) are sometimes called, saw significant economic recovery amidst the lingering specter of foreign debt, as well as the partial or full renationalization of many previously privatized services, including Correo Argentino (the postal service) in 2003, Aguas Argentinas (water) in 2006, Aerolineas Argentinas and $30 billion in pension funds in 2008, Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales, or YPF (energy) in 2012, and Ferrocarriles Argentinos in 2015.39 The latter move was precipitated by several tragedies that highlighted the liabilities of private ownership of formerly public services. On October 20, 2010, a student activist, Mariano Ferreyra, was killed by Confederación General del Trabajo–affiliated, Peronist Unión Ferroviaria supporters in Buenos Aires while protesting with laid-off workers from the Roca Line.40 On February 23, 2012, fifty-one people were killed and 702 injured when a Sarmiento Line commuter train failed to brake as it entered Once station in Buenos Aires, slamming into the restraint barrier at twenty-six kilometers an hour and obliterating the locomotive and first several coach cars. It was worst rail accident in Argentina in thirty years, one of several between 2011 and 2013.41 Larrambebere’s painting Once (2012), based on a pixelated digital photograph of the wreck, commemorates the event at the disturbing remove of online journalism—a markedly different register of representation than his paintings of stations between 1996 and 1997.

In 2014, with Cristina Kirchner taking a stand against “vulture funds,” Argentina again defaulted on IMF loan payments—a sign of more trouble to come. Part of a worldwide swing to the right over the last four years, Mauricio Macri became president of Argentina on December 17, 2015. One of his first moves was to devalue the peso, allowing it to fall 30 percent to once again open the country to foreign investment.42 At the end of 2017, he passed a pension reform that led to mass protests, and their wider privatization is believed to be on the table in the coming elections.43 All along, inflation has soared and the economy has shrunk as an economic crisis has emerged and deepened. In September 2018, Macri negotiated a new, $57.1 billion loan from the IMF—the largest in its history, making a commitment to a zero deficit for 2019 that guarantees more austerity measures. He has sold government stakes in electricity companies, privatized the country’s recreation centers and threatened to reprivatize the airline following one strike action. Rather than discuss the privatization of Ferrocarriles Argentinos outright, he has closed several lines and had the tracks lifted, leaving the land beneath open to potential sale. Unsurprisingly, in this same period, ABTE has lost its access to the Museo Nacional Ferroviario where its para-institutional operations first began.

On February 1 of this year, ABTE performed a new action at a fully functioning Coghlan Station on its 128th anniversary. Signs were repainted and Larrambebere, clad in overalls and a vintage cap, lectured the public via megaphone. “Coghlan, si, colonia no. Viva Coghlan.” Given the highly local specificity of ABTE’s reference points and histories, the question could be raised whether it is even compatible with any model of the “global contemporary,” or need be. That said, the group certainly fits within a more nuanced and internationalized discussion of so-called “social practice,” which has in the last twenty years gone by various monikers including “relational aesthetics,” “service aesthetics,” and “social engagement,” among others, and been celebrated as a global phenomenon.44 But, however much a formation like ABTE could be compared with the likes of Thomas Hirschhorn or Theaster Gates, its significance can only be appreciated in terms that are well researched and appreciated from the point of view of the local, rather than as an Argentinean entry in a homogenized global trend. In a promising sign, the Pacific Standard Time exhibition “Talking to Action: Art, Pedagogy, and Activism in the Americas” recently examined “dialogically-driven, community-based art making” throughout the region.45 The show included Eduardo Molinari as well as Iván Puig Domene and Andrés Padilla Domene’s Sonda de Exploración Ferroviaria Tripulada (Abandoned Railways Exploration Probe, 2010), or SEFT-1, a futuristic vehicle built to navigate railways abandoned by privatization in the artists’ home country of Mexico. The concept closely recalls a similar vehicle conceived by ABTE, the Railcar Viable (2005), “a machine for generating thought and relationship[s].” While playing on the aesthetics of science fiction rather than nostalgia, the echoes of ABTE’s poetics and approach are a reminder of the relevance of railways for multiple afterworlds of neoliberalism. While such a practice is unlikely to ever break into the global art market, ABTE succeeded in its original goals of activating the past and insisting on the outmoded, maintaining their visibility and value. It brings to mind a reflection by Eduardo Molinari, in a recent interview about his own work: “What are the memories you’d be interested in preserving? What is valuable to remember in order to pass on to new generations? … Does the free circulation of these memories exist today?”46

Sarah Lloyd, “Ticketing the British Eighteenth Century: ‘A thing … never heard of before,’” Journal of Social History 46, no. 4 (2013): 844. The earliest prototypes of steam-driven locomotives were produced at the end of the eighteenth century, with the British railways—initially as short local rail links run by separate private companies—beginning operations in the 1830s. In 1840, the Act for Regulating Railways placed these private companies under a minimum form of centralized government control, although a bill to nationalize the system in 1844 was not passed, with this only taking place much later, during World War I.

Lloyd, “Ticketing the British Eighteenth Century,” 860. Lloyd argues that in the nineteenth century, it was precisely the use of tickets for “railways and trams” that “weighted down” their adept fluidity across culture and “social contexts.” Edmondson’s invention in particular, with its removal of the human hand from the process of ticket production, would seem to support Lloyd’s contention that in modernity, a “rage for system” began to win out over a certain informality and heterogeneous use.

The idea that ABTE is in part or in whole a “fictional” entity has attended writing on the group from its origins through its 2013 retrospective at the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires. Yet this deployment of fiction should not be confused with contemporaneous strategies premised on “games with the truth,” as in the “parafictional” practices identified by Carrie Lambert-Beatty. While ABTE was not any sort of officially existing body, it did serve to connect actual ticket collectors and railway enthusiasts, just as its unsanctioned interventions at railway sites nonetheless took the form of material alterations to station infrastructure. See Agustín Diez Fischer, “Viajes Ferroviarios con Boletos de Carton,” in 57 × 30,5 mm.: Quince Años de Cultura Ferroviaria ABTE, exh. cat. (Buenos Aires: MAMBA, 2015), 61; Andrea Giunta, Poscrisis: Arte Argentino Después del 2001 (Buenos Aires: Siglo Veintiuno Editores, 2009), 169; and Carrie Lambert, “Make-Believe: Parafiction and Plausibility,” October, no. 129 (Summer 2009): 51–84.

Valeria González, En Busca del Sentido Perdido: 10 Proyectos de Arte Argentino, 1998–2008, exh. cat. (Buenos Aires: Papers Editores, 2010), 20–33.

Situationist International, “Definitions,” in Situationist International Anthology, ed. Ken Knabb (Bureau of Public Secrets, 2006), 51–52.

In the United States, institutional interest in modern and contemporary Latin American art has been most recently exemplified by the Getty Foundation’s “Pacific Standard Time: LA / LA” initiative, which opened some sixty simultaneous exhibitions in the Fall of 2017, among many other examples. For an eloquent critique of the “pseudomorphism” that frequently attends “global contemporary” exhibitions and paradoxically subsumes non-Western art under Western paradigms, see Kaira M. Cabañas, Learning From Madness: Brazilian Modernism and Global Contemporary Art (University of Chicago Press, 2019), 143–46.

These years correspond to the implementation of neoliberal shock tactics in nations around the world, but Harvey also points to the key date of 1947, when Friedrich von Hayek created the Mont Pelerin Society in the company of Ludwig von Mises, Milton Friedman, and others. See David Harvey, A Short History of Neoliberalism (Oxford University Press, 2005), 1 & 20. Harvey’s understanding of late capitalism’s colonization of public space is also directly relevant to ABTE’s railway interventions, particularly his understanding of “relational space,” in which “there is no such thing as space or time outside of the processes that define them.” See: David Harvey, Spaces of Global Capitalism: Toward a Theory of Uneven Geographical Development (Verso, 2006), 123.

See Mario Justo López and Jorge Eduardo Waddell, Nueva Historia del Ferrocarril en la Argentina: 150 Años de Política Ferroviaria (Buenos Aires: Lumiere, 2007), 157–76.

See Daniel James, Resistance and Integration: Peronism and the Argentine Working Class, 1946–1976 (Cambridge University Press, 1988).

Ravi Ramamurti, “Testing the Limits of Privatization: Argentinean Railroads,” World Development, vol. 25, no. 12 (1997): 1976.

Even before the military coup, Isabel Perón’s rule was compromised by economic shock measures known as the “Rodrigazo” (after then-economy minister Celestino Rodrigo), instituted on June 4, 1975: a 160 percent devaluation of currency for the commercial exchange rate; a 100 percent increase in utility and transportation prices; a 180 percent rise in the price of fuel; and a 45 percent increase in wages (which was insufficient to boost the “real wage” in relationship to the new rate of exchange). The inflation rate climbed to 35 percent per month, leading to a general strike, instability, and fertile terrain for the military coup that followed in March 1976. See David Rock, Argentina 1516–1987: From Spanish Colonization to Alfonsín (University of California Press, 1987), 365–66.

See Raúl García Heras, “The Return of International Finance and the Martínez de Hoz Plan in Argentina, 1976–1978,” Latin American Research Review 53, no. 4 (2018): 799–814. Martínez de Hoz was indicted for human rights abuses in 1988 and pardoned by Menem, along with the rest of the junta, in 1990, leaving him free to return to business. Among other endeavors, he joined the board of Banco General de Negocios, which would later help its clients wire some $30 billion out of the country just before the 2001 economic crisis.

See William C. Smith, “Democracy, Distributional Conflicts and Macroeconomic Policymaking in Argentina, 1983-89,” Journal of Interamerican Studies & World Affairs 32, no. 2 (Summer 1990): 1–43.

Osvaldo Soriano, “Living with Inflation,” trans. Patricia Owen Steiner, in The Argentina Reader: History, Culture, Politics (Duke University Press, 2002), 483–85.

William C. Smith, “State, Market and Neoliberalism in Post-Transition Argentina: The Menem Experiment,” Journal of Interamerican Studies & World Affairs 33, no. 4 (Winter 1991): 45–83.

See Santiago Duhalde, “Neoliberalismo y Nuevo Modelo Sindical: Los Trabajadores Estatales Durante la Primera Presidencia de Carlos Menem,” Espacio Abierto Venezolano de Sociología 19, no. 3 (July–September 2010): 417–43; and Alfredo Pucciarelli, Los Años de Menem: La Construcción del Orden Neoliberal (Buenos Aires: Siglo Veintiuno Editores, 2011).

Vicente Palermo, “The Origins of Menemismo,” in Peronism and Argentina, ed. James P. Brennan (SR Books, 1998), 141–76.

Ramamurti, “Testing the Limits of Privatization,” 1973.

See Juan Carlos Cena, El Ferrocidio (Buenos Aires: La Rosa Blindada, 2003).

See Lucio di Matteo, El Corralito (Buenos Aires: Sudamericana, 2013).

María Guillermina Fressoli, “El Recuerdo como un Problema del Espacio Pictórico en los Paisajes de Patricio Larrambebere,” Hallazgos 13, no. 25 (September 2015): 147–48.

Luis Felipe Noé, “Otra Figuración,” in Inverted Utopias: Avant-Garde Art in Latin America, eds. Mari Carmen Ramírez and Héctor Olea, exh. cat. (Yale University Press, 2004), 481. See also Patrick Frank, Painting in a State of Exception: New Figuration in Argentina, 1960–1965 (University Press of Florida, 2016).

Artists who made such representational turns during the Proceso include Oscar Bony, Margarita Paksa, Pablo Suárez, and Nicolás García Uriburu. Antonio Berni, a representational painter his entire career, nonetheless produced haunting images in this period that belong in this subgenre. I have written about Bony’s painting at this time; see Daniel R. Quiles, “Between Organism and Sky: Oscar Bony, 1965–1976,” Caiana Journal, no. 4 (July 2014): 1–14. See also Viviana Usubiaga, Imágenes Inestables: Artes Visuales, Dictadura y Democracia en Buenos Aires (Buenos Aires: Edhasa, 2012).

Fressoli, “El Recuerdo como un Problema,” 137.

Fischer, “Viajes Ferroviarios con Boletos de Carton,” 68.

See Teresa Riccardi, “Archivo Caminante: Constellations and Performativity,” Afterall, no. 30 (Summer 2012): 76–85.

Patricio Larrambebere, “Artes Visuales, Pintura y Ferrocarril. Edmondsonianismo,” in 57 × 30,5 mm., 106, my translation.

See Recovering Beauty: The 1990s in Buenos Aires, ed. Ursula Dávila-Villa, exh. cat. (Blanton Museum of Art, 2011). Although her career was established before the heyday of Rojas, Liliana Maresca should also be mentioned in any discussion of 80s/90s art, the readymade, and critique of menemismo. See: María Gainza, ed., Liliana Maresca, exh. cat. (Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires, 2016).

See Pombo, ed. Inés Katzenstein (Buenos Aires: Adriana Hidalgo editora, 2006).

Sebastián Gordín: Un Extraño Efecto en el Cielo, ed. Victoria Noorthoorn, exh. cat. (Buenos Aires: Museo de Arte Moderno, 2014), 126–29.

Giunta, Poscrisis, 19, my translation.

Giunta, Poscrisis, 55, my translation. Giunta also wrote a short review of ABTE’s “temporary headquarters” at Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires in 2003; see ibid., 169–71. See also: Ana Longoni, “A Long Way: Argentine Artistic Activism of the Last Decades,” in Collective Situations: Readings in Contemporary Latin American Art, 1995-2010, eds. Bill Kelley Jr. and Grant H. Kester (Duke University Press, 2017), 98-112.

Marina Sirtin, Everyday Revolutions: Horizontalism and Autonomy in Argentina (Zed Books, 2012), 3. “Horizonality,” Sirtin writes, “is a social relationship that implies, as its name suggests, a flat plane upon which to communicate, but it is not only this. Horizontalidad implies the use of direct democracy and striving for consensus: processes in which attempts are made so that everyone is heard and new relationships are created. Horizontalidad is a new way of relating based in affective politics and against all the implications of ‘isms.’ It is a dynamic social relationship. It is not an ideology or set of principles that must be met so as to create a new society or new idea. It is a break with these sorts of vertical ways of organizing and relating, and a break that is an opening,” ibid., 9. See also Sitrin, Horizontalism: Voices of Popular Power in Argentina (AK Press, 2006).

See Justin McGuirk, Radical Cities: Across Latin America in Search of a New Architecture (Verso, 2014), 49–66.

Here I am thinking of the numerous reports of the “resilience” of the Puerto Rican people in the wake of Hurricane Maria in 2017, which bore, consciously or unconsciously, the implicit suggestion that this was proof that they did not need help from the US government.

Javier Barrio, “Lisergia Ferroviaria: Visiones y Ocultamientos en Open Door,” in 57 × 30,5 mm., 174, my translation.

Svetlana Boym, The Future of Nostalgia (Basic Books, 2001), 76. The quotation is from Michel de Certeau and Luce Giard’s The Practice of Everyday Life, vol. 2.

As Luigi Manzetti notes, Néstor Kirchner had supported privatization under Menem, who was also a Peronist, but renationalization proved enormously popular in the wake of 2001. Luigi Manzetti, “Renationalization Under the Kirchners,” Panoramas (Center for Latin American Studies, University of Pittsburgh), November 23, 2016 →.

Despite Macri’s imposition of the harshest austerity program since the 2001 crisis, the international press has cast him as an improvement over the Kirchners precisely for his willingness to work with the international financial interests controlling Argentina. This portrayal of Macri is typified by a scandalous recent New York Times article that blames Argentina’s financial woes on the Kirchners’ “populism” and “unbridled spending.” The article does not even mention the Menem years or his policies. See Peter S. Goodman, “Argentina’s Economic Misery Could Bring Populism Back to the Country,” The New York Times, May 10, 2019, →.

Elizabeth González, “Is Pension Reform on the Ballot in Argentina’s Election?” Americas Society / Council of the Americas Bulletin, March 29, 2019 →.

Nato Thompson, “Living as Form,” in Living as Form, exh. cat. (MIT Press, 2011).

Talking to Action: Art, Pedagogy, and Activism in the Americas, ed. Bill Kelley, Jr., exh. cat. (Otis College of Art and Design, 2017), 7. For an important precedent of this exhibition, see Agítese antes de Usar: Desplazamientos Educativos, Sociales y Artísticos en América Latina, eds. Renata Cervetto and Miguel A. López, exh. cat. (Buenos Aires: Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires, 2016).

“A Conversation Between Eduardo Molinari and Nuria Enguita Mayo,” trans. Tamara Stuby, Afterall 30 (Summer 2012): 70.