The self is constituted by others; everybody is somebody’s Jew. Look to the Muslims murdered en masse in the Middle East, harassed and killed in the United States; the war against black lives carried out by cops and klans and right-wing terrorists; the classist eugenics performed on the poor by the extractive networks of capitalism; the Native victims of cultural and natural destruction via unregulated development of indigenous lands; the many displaced by the gentrification of urban space. And no matter who you are, at one point or another in your life, you are your own Jew.

Re-Membering

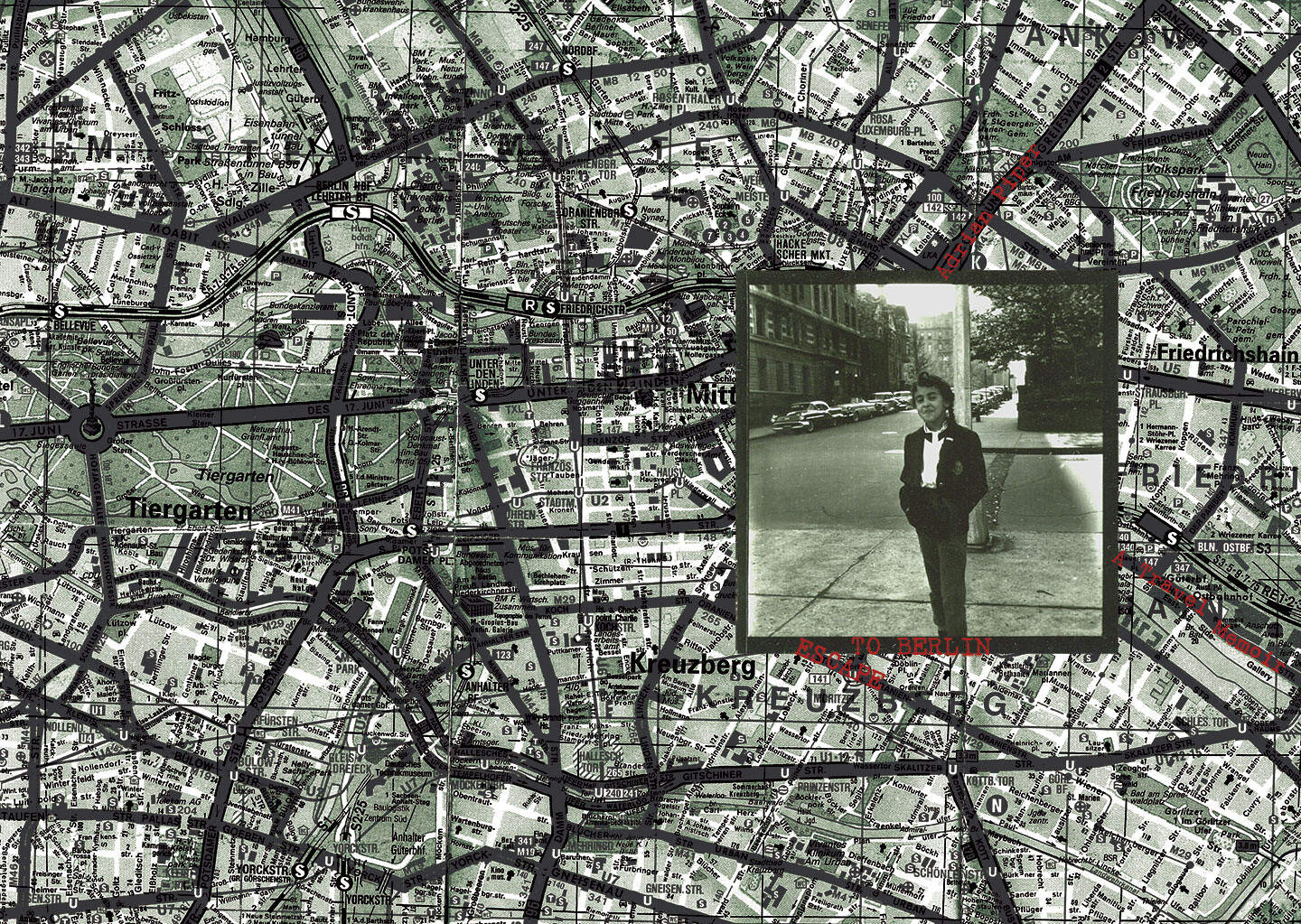

To re-member is to reassemble the limbs of history. How shall we put together this pandemic event? Shall we affect amnesia—and not recall awkward heroes, principles, and politics? The grief about contemporary loss of truth—of not feeling truly at home—manifests as nostalgic attempts to re-present critical events through staged recreation. At the same time, to write about present activities is to create distance between oneself and the event—to move to from participant to observer. Who authors what history? The following essays have been selected for their insights into the re-creation of memory, forgetting, and identity.

It is particularly dangerous when something from the cultural imagination is later read as a reliable prophecy, since it renders the abstraction and alienation of human suffering as a set of perpetuating clichés. For example, the only similarity between the current pandemic and the “predictions” pulled from Dean Koontz’s 1981 novel The Eyes of Darkness, noted on social media this February, is a reference to a killer virus called “Wuhan-400” that emerged from the Chinese city of Wuhan. As the reality of the pandemic unfolds globally, “China” continues to operate as a spectacle in both intellectual gossip and pop-cultural speculation. But we need more than just an arbitrary imagination of the suffering. There is rage, confusion, fear, and despair: concrete and real.

In their collective formations, postcrisis practices in Argentina paralleled larger changes in social movements towards self-organization, and horizontalidad, or horizontality. Marina Sirtin defines horizontality as “a form of direct decision making that rejects hierarchy and works as an ongoing process.” Horizontalism and self-organization imply modes of production that no longer depend on the government for help—although some such groups received funding from Néstor and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner’s successive administrations. ABTE adapted two horizontalist characteristics: leaderless organization and the performance of extra-governmental services. Yet ABTE’s labor was artistic precisely insofar as it was no longer necessary, existing in the breach between past and present. The group sidestepped a neoliberal reading of horizontalism as proof of the “resilience” of groups left to subsist without government support, which ironically justifies further reduction of state services. It also refuses any reading of “social practice” as proof that contemporary art might supplement development or services that a state could provide.

“Everything will be taken away,” depending on the context, takes on different meanings, but it is always with the same underpinning: loss is always occurring, but there is also a sense of relief at being able to let go of attachments. Piper’s memoir allows you to read very concrete meaning into this in regard to her professional affiliations in US academe and the US art world: being abandoned by all those depicted in the erased snapshots made it easier for her to leave behind the country from which she has taken exile.

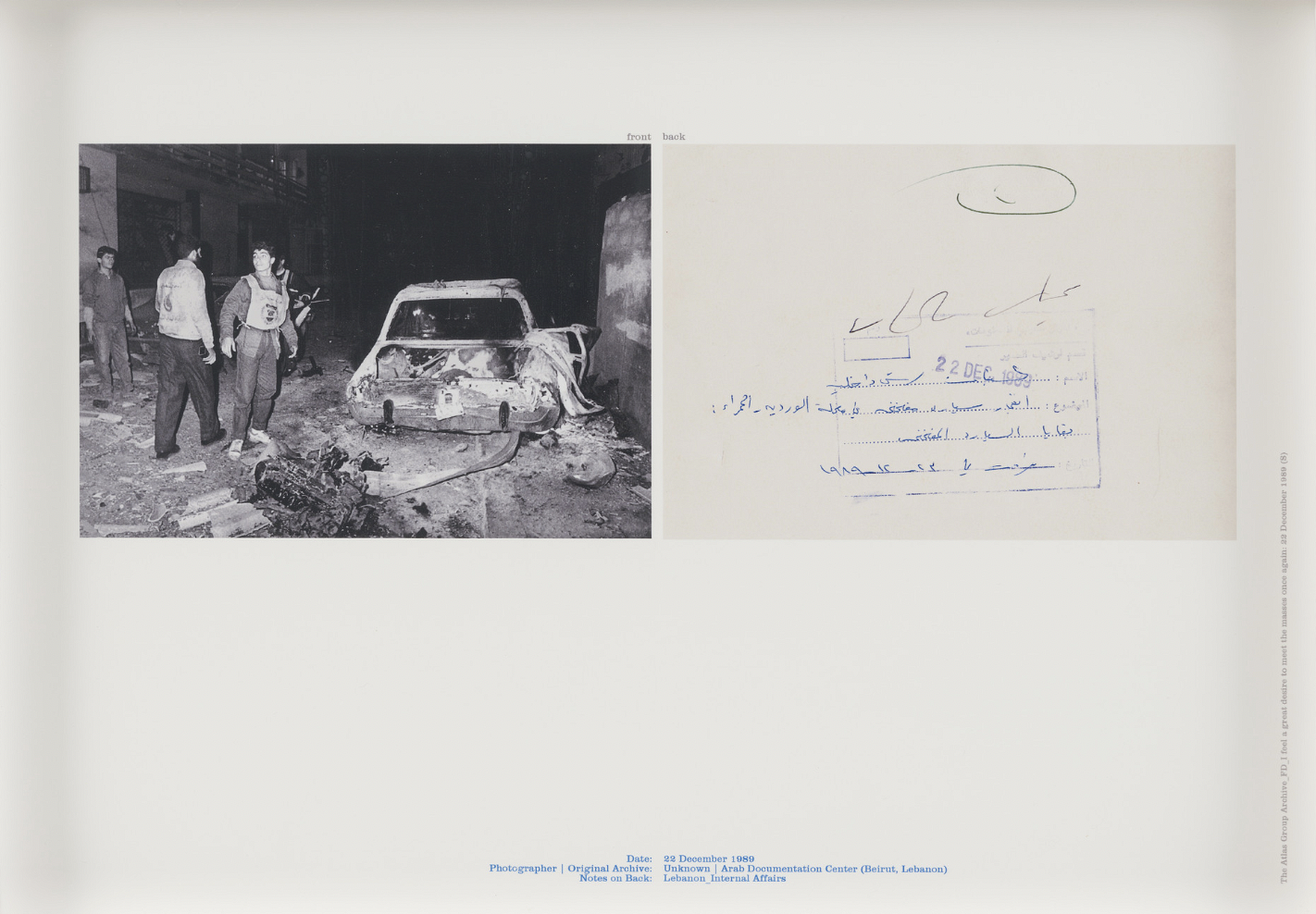

It may be a cliché to say that the past, from the perspective of the present, looks like a field of ruins for the historian to excavate. But our past, then, was literally a field of ruins, not for excavation, but for reconstruction and pillaging. We emerged from the civil war into a violent reconstruction process, governed by a postwar settlement that was characterized by “state-sponsored amnesia,” and a genuine desire to forget past horrors. We rushed into the future because we had no past, at least no past that could provide us with a sense of belonging, meaning, or continuity with what had come before. We were the product of a rupture, and we became the vanguard by default.