April 17–September 15, 2024

Walking through this exhibition of some 250 works by nearly a hundred artists working in the former Eastern Bloc, I was forced at one point to turn back and re-enter it through the exit so that a mess left by a “service” dog could be cleaned up. Doubling back to go forward was an apt metaphor, I thought, for the frequent adjustments to circumstances that these artists working either unofficially or within the “second public sphere” had to perform throughout the period covered by this major historical overview.1

Indeed, one of the biggest accomplishments of a show covering six former countries that constitute nine present-day ones (Poland, Romania, Hungary, the former East Germany, Czechoslovakia, and Yugoslavia) is that it conveys the complex lived reality of artists who, while making work for the same multifaceted reasons as their peers elsewhere in the world, were constrained by various degrees of state hostility during a series of asynchronous national “thaws” and “freezes” imposed by the Soviet “brother.”

The exhibition is noteworthy for how much it tries to accomplish and the possibilities for discovery it offers, with works ranging from heartbreaking to whimsical. Organized into four large sections, it covers the themes of “Public and Private Spaces of Control,” “Dimensions of the Self,” “Being Together: Alternative Forms of the Social,” and “Looking to Other Futures: Science, Technology, Utopia,” with an additional smaller section on “Networks of Exchange: Cross-Cultural Dialogues In and Out of the Bloc.”2 The works that brought me delight included Zbigniew Rybczyński’s short film Oh! I can’t stop! (1975), one of the first things you encounter, made by the filmmaker before his 1983 emigration and later success in the West as a pioneer of audiovisual technology. The film is subtly political in its literalization of the idea that life under state-socialism amounts to hitting a wall, but it’s also astonishing technically—like a journey through Google Street View but surreally playful and analog (it was made at the state-run Se-Ma-For Studio in Łódź).

Seeing a recreation of Gyula Konkoly’s Bleeding Monument (1969/2023) was, by contrast, a gut punch. It emblematizes both the power of many of the works in the show and their context-dependent, performance-based elusiveness. It resembles a deathbed with a missing body evoked by bloodlike potassium permanganate stains on gauze bandages. At the time when it was made, the piece was an Aesopian way of semi-publicly mourning the losses (of life, independence, dignity) caused by the Soviet invasions of Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968. Today, the piece also speaks, at least for me, to Eastern Europe’s challenges with publicly memorializing and assessing with any finality the legacies of the state-socialist period, which left no single “body” to lay to rest.

Janina Tworek-Pierzgalska’s sculptural installation Places (1975) centers a depiction of a woman’s body while speaking to a more universal experience of fragmented self-perception and spiritual seeking, leaving me intrigued to see more by this little-known figure. After years of wondering about them, it was a true joy to hear Katalin Ladik’s unabashedly weird “sung” soundscapes, created in conjunction with her inventive collages and best described as Foley on steroids, but minus the narrative that makes sense of cinematic sound effects. Finally, the installation of objects Július Koller made over several decades to explore ping-pong as a pretext for communal togetherness and metaphor for fair play is the best I’ve seen of this work. Adding a mirror to one half of a ping-pong table, thus inviting viewers to imagine themselves playing the game with Koller, is a move ingenious in its simplicity and effectiveness.

Curator Pavel Pyś’s serious engagement with current scholarship is reflected in the show’s key choices: its regional and thematic (rather than nation-state) focus; its demonstration of the ways Eastern European culture was not completely isolated behind the Iron Curtain and shared in international artistic concerns; its extensive representation of “new media” (performance, moving image, kinetic, installation, fiber, digital, and intermedia art); its choice to frame its main ideas around “experimental” work (rather than using more loaded terms such as “avant-garde,” “unofficial,” or “dissident”); its acknowledgment that experimental work was produced both outside and inside state-run institutions; and its commitment to not reducing every creative gesture to an up or down vote on state-socialism.

The curatorial team also put impressive effort into mapping out the history of what for US art institutions is a terra incognita in the first survey of this scale in North America, created thirty-five years since the collapse of the Eastern Bloc and the USSR began in 1989. Placed throughout the exhibition are wooden structures that offer socio-historical context, and there is a fifty-five-page illustrated “primer” on regional history at the entrance (though I didn’t see anyone beside myself crack it open).

Despite its strengths, the selection of the works in the exhibition also left me wondering whom the curator was imagining as his audience. It often felt like it was a viewer like me, someone looking for new discoveries and insights after already being well acquainted with the “big names” and “canonical” works, rather than a novice encountering art from this region for the first time. The unevenness of the show’s checklist was perplexing.

In the cases of the Prague, Bratislava, and Bucharest art scenes, for example, the best-known artists (Milan Knížák, Jiří Kovanda, Július Koller, Stano Filko, Ion Grigorescu, Geta Brătescu) are all represented alongside exciting lesser-known figures (Jan Ságl, Zdeňka Čechová, Ľubomír Ďurček, Matei Lăzărescu). Yet in the case of the bigger and more heterogeneous Polish, Hungarian, and Yugoslav art scenes, where were Marina Abramović and Raša Todosijević to represent the community around the Student Cultural Center in Belgrade in a show that foregrounds performance art? Where was Tadeusz Kantor, a transnational polymath who has a whole remarkable museum dedicated to him in Kraków? Or Magdalena Abakanowicz, missing from a show that stresses the freedom to experiment that women in the region found by working with fibers and textiles? Where was Miklós Erdélyi, who mentored and inspired two generations of experimental artists working across multiple media in Budapest, and Oskar Hansen, who did the same in Warsaw?

That these figures are mentioned in the excellent but sprawling curatorial essay in the catalogue fails to capture their influence. While the show still holds together thematically, it is not clear whether such omissions were a deliberate, unfortunate choice or something else (such as unacknowledged exigencies stemming from what could or couldn’t be secured, insured, and shipped as loans?).

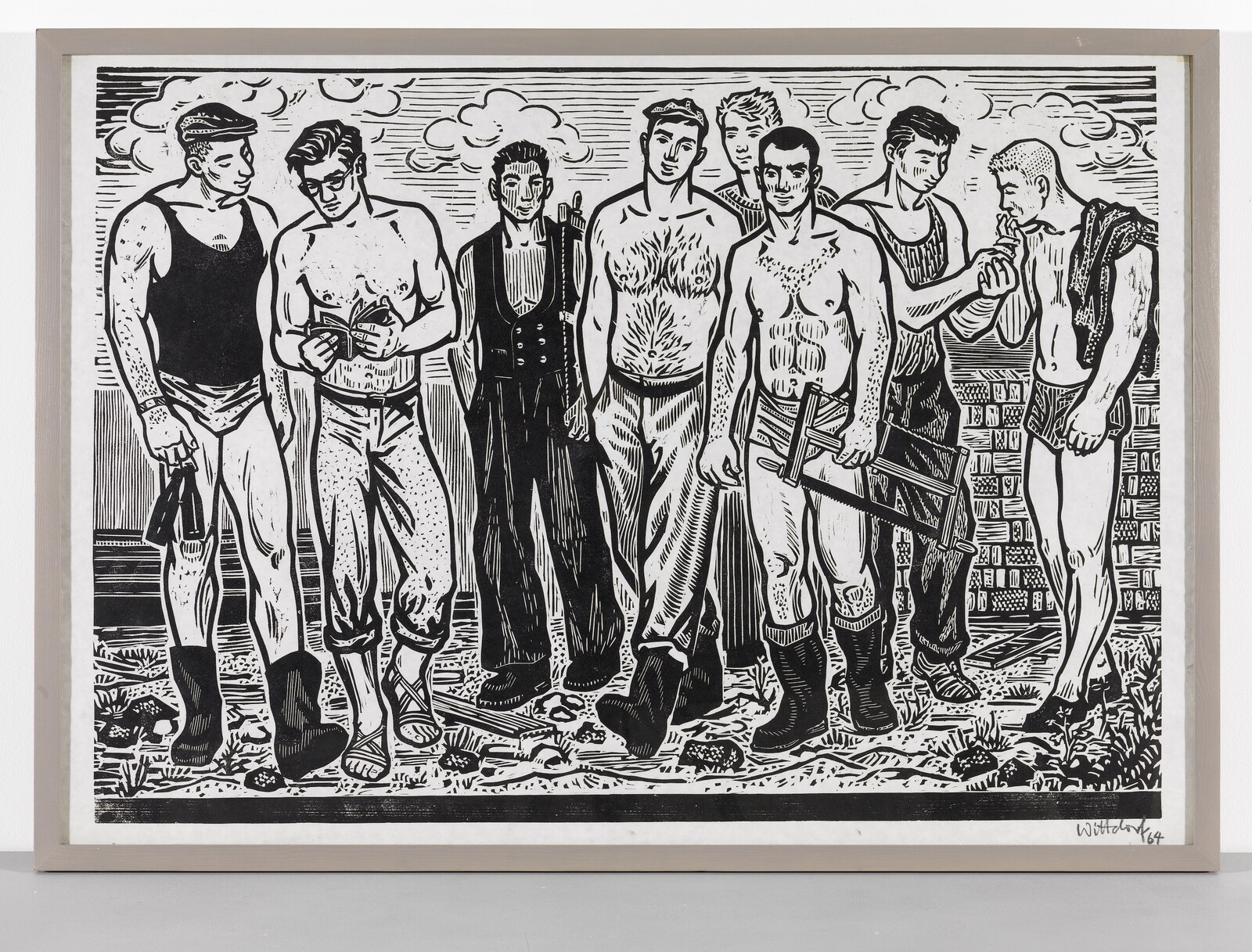

Most of the artists missing from this narrative were straight European men—a group overrepresented in art history as a whole, but also irreplaceable to the story of this time and place. The show’s strong emphasis on feminist and queer histories from the region (which dominates in the “Dimensions of the Self” section and is very present in Phoenix in “Networks of Exchange”) is both a strength and a drawback, to the extent that it overshadows other possible foci. Foregrounded works include, among others, those made by queer artists (for example Jürgen Wittdorf, whose woodcuts, comparable to works by Paul Cadmus, are homoerotic yet anything but formally experimental); those made about queer subjects/communities (including documentary photographs by Libuše Jarcovjáková); or those resonant with Western feminism (iconic pieces by Natalia LL and Sanja Iveković, both produced in countries where western-style consumerism made the biggest inroads in the 1970s).

In choosing to foreground these works, the show is both rooted in contemporary scholarship (the catalog has a thorough roundtable discussion on queer archives) and linked to matters of contemporary political urgency. In Poland, “LGBT-free zones” were legal up until this year, and abortion is virtually inaccessible. Public anti-queer sentiment remains strong in many parts of the region, and the situation of women has, in at least some respects, arguably gotten worse since 1989.3 As an engaged citizen, I get why foregrounding these legacies is important. Yet as a historian, I worry that visitors might leave the show with the mistaken idea that there is little daylight between the social stances and agendas of Eastern European dissidents/unofficial artists/cultural intelligentsia of the socialist era and present-day culture workers based everywhere from Brooklyn to Berlin to Bucharest.

Some big omissions here have to do with the region’s notoriously complex ethnic and religious make-up, made messier by the legacy of World War II, as well as a broad spectrum of opinions concerning socialism, at least through the mid-seventies. In all its multiple realities, this show ignores how issues such as anti-Semitism, prejudice against the Roma, desire for religious freedom, or efforts to reclaim a purer form of “socialism with a human face” were, for better or worse, more prominent in the public discourse of Eastern Europeans interested in “alternative forms of the social” from the sixties through to the eighties than gay liberation or women’s rights as understood in the West. These are not small things, and leaving them outside the show’s narrative is at best a missed opportunity.

“Multiple Realities” does convincingly demonstrate that, pace the stereotypes of a gray and monolithic cultural wasteland, Eastern Europe under state-socialism did produce multiple, heterogeneous realities.4 Many of the works and themes presented here could open out onto both future solo retrospectives and thematic exhibitions, thus integrating them into a global art history. I can imagine a show, for example, tracing the careers of the artists from state-socialist countries who became diasporic, creating complex dialogues between their “old” countries and new cultural homes (mostly in the West). I deeply hope that this exhibition, rather than closing the book on its subject, will open doors for more explorations.

“Multiple Realities: Experimental Art in the Eastern Bloc, 1960s–1980s” was organized by the Walker Art Center (November 11, 2023–March 10, 2024) and travels to Vancouver Art Gallery (December 14, 2024−April 21, 2025).

The term “second public sphere” comes out of the work of Hungarian sociologists Elemér Hankiss, Miklós Haraszti, and György Konrád. It is now widely used by cultural historians of the region after being popularized by the book Performance Art in the Second Public Sphere: Event-Based Art in Late Socialist Europe, eds. Katalin Cseh-Varga and Adam Czirak (New York: Routledge, 2018). See Stefanie Proksch-Weilguni, “Performance Art in the Second Public Sphere,” ARTMargins (April 15, 2019), https://artmargins.com/performance-art-in-the-second-public-sphere/.

The exhibition layout described here pertains to the Phoenix Art Museum presentation. Based on reading reviews of the Walker Art Center presentation, I believe it was somewhat different there and concentrated works focused on queer representation and feminist ideas in closer proximity to each other.

Slavenka Drakulić offers an excellent discussion of the complexities of this question here: https://www.iwm.at/transit-online/how-women-survived-post-communism-and-didnt-laugh.

Critic Peter Plagens nonetheless described this exhibition as “comparatively cold, gray, but occasionally lively,” lest we forget that the adjectives “cold” and especially “gray” must be mandatorily applied to any mention of Eastern Europe. See “‘Multiple Realities: Experimental Art in the Eastern Bloc’ Review: Creativity Under Soviet Constraints,” The Wall Street Journal (December 28, 2023), https://www.wsj.com/arts-culture/fine-art/multiple-realities-experimental-art-in-the-eastern-bloc-review-walker-art-center-minneapolis-f7848c35.