Chantal Akerman once told an interviewer that each of her films needs hallways, doors, and rooms. “Those doors and hallways help me frame things, and they also help me work with time.”1 Akerman’s first major retrospective in her native Brussels showcases the breadth of her time-based achievements across an art-deco labyrinth one could spend days within. The exhibition opens with digital restorations of four 8mm films submitted with Akerman’s 1967 application to art school. Projected alongside each other asynchronously, the silent snapshots drift between frenetic observation and acted scenes with Akerman’s mother and friends. These are the earliest examples of Akerman’s radical filmmaking that she would go on to call “documentary bordering on fiction.”2 A cinema of ethically crossing thresholds.

“Travelling” puns with the French travelling, or tracking shot. Akerman’s camera often moved right-to-left, working against the Hollywood standard of narrative progression and challenging preconceptions of what constitutes an advance. People are in transit in Akerman’s films, and the camera moves with them. Subjects exit train stations, check into hotels, ride the subway, and queue for buses. Les Rendez-vous D’Anna (1978), Akerman’s first film with major distribution, is almost entirely composed from travel passages. Not screened in the exhibition but represented by the script, set and location-scouting photographs, and the press packet, the film follows a young filmmaker through Europe. In Akerman’s words, relayed via the accompanying wall text, Anna makes the “journey of an exile, of a nomad who owns none of the space she moves through.” The past haunts the present in Akerman’s perfect compositions that look so openly at the architecture of German train stations and the people who move through them.

Near the materials from Anna, a monitor with two sets of headphones plays Dis-moi [Tell Me], Akerman’s 1980 TV documentary in which she interviewed grandmothers who survived the Holocaust. Akerman’s mother escaped an Auschwitz death march and never spoke about it, an absence that Akerman referred to as a “kind of hole that [she] needed to fill and that [she] went looking for through films, words and people.” Natalia Akerman does not appear in Dis-moi, but her voice does. She speaks about her own mother, Chantal’s grandmother. This intimate storytelling is audible only to those sitting with the headphones in front of the monitor at BOZAR. If you are standing nearby, you might see a beautiful red sweater and elegant china while hearing high heels and stage directions from Akerman’s meta-musical Les Années 80 [The Eighties] (1983).

Akerman began developing museum installations out of her film work in the 1990s, when the Walker Art Center commissioned an artwork reflecting on the reunification of Europe. In response, Akerman adapted the film D’Est [From the East] (1993) into the video installation From the East: Bordering on Fiction (1995). Working with her longtime collaborator Claire Atherton, Akerman transferred D’Est’s wordless, polyphonic 35mm portraits to eight video triptychs installed at eye level. Walking among the banks of images dilates the sense of time, of waiting, and the effect of the coordinated camera movement to the left.

In another of the quotes scattered through the show, Akerman describes her intention for the viewer to “have the physical experience of time unfolding inside you, of time entering you.” At BOZAR, the glow of the twenty-four screens and the din from the twenty-four audio channels envelop visitors tracking along the paths. A twenty-fifth channel in a small room behind the array invites people, writes Atherton in the exhibition catalog, to “tend toward something.” On a monitor installed on the floor, a blurry view of the Moscow night sky plays backward: a grainy abstraction interrupted by the occasional traffic light. There is cello music and Akerman’s voice reciting a singular, urgent conclusion to a diffracted experience of evacuation. She speaks of “faces and bodies placed side by side, faces that vacillate between a strong life and the possibility of a death that would come to strike them without their having asked for anything.”

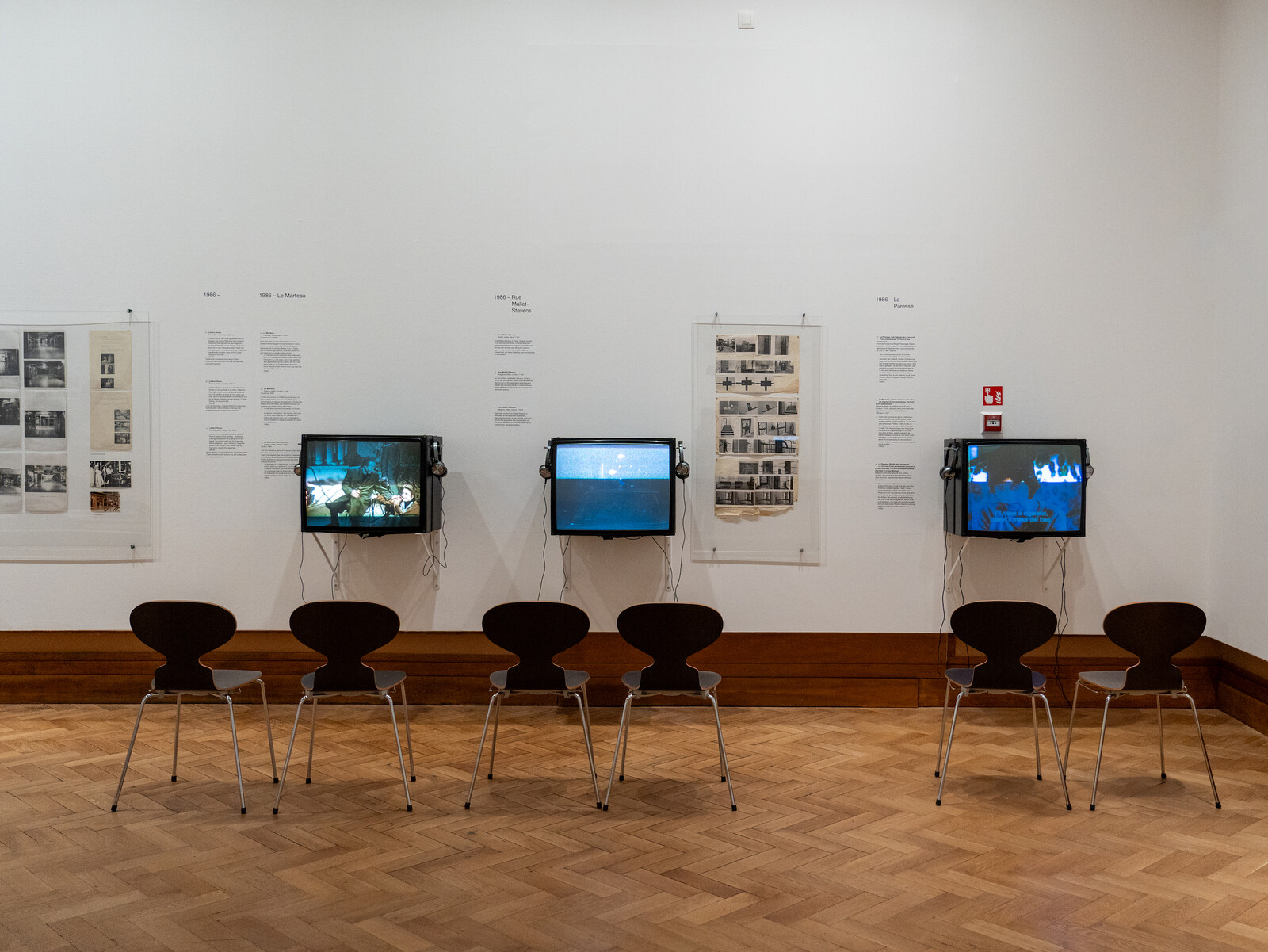

From the earliest single-channel works, and increasingly in expanded formats, Akerman’s cinema isolated faces from the masses, finding something particular that resists uniformity. “Travelling” offers a robust and clear presentation of the work, laying out how relentlessly it shifted in style and mode yet remained consistent in its vision. Throughout “Travelling,” Dutch, French, and English wall texts form a detailed timeline of Akerman’s life and production, while a central room contains computers and binders of archival materials.

The exhibition concludes with four installations. Woman Sitting After Killing (2001) is an arc of seven monitors on pedestals that loop the final five minutes of Akerman’s 1975 avant-garde breakthrough Jeanne Dielman, 23, Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles. As the dazed title character is deluged sevenfold by what her routines had kept at bay, the staggered screens extend the denouement into an elliptical eternity. A Voice in the Desert contains an excerpt of Akerman’s US/Mexico border documentary De L’Autre Côté [From The Other Side] (both 2002) projected in the desert at dawn. The artist speaks in Spanish and English about labor, migration, and disappearance as the sky slowly brightens.

When asked what obsesses her, Akerman once listed “history, the big and small, fear, mass graves, hatred of the other, of oneself, and also the dazzle of beauty.”3 In the installations, working even more intricately with time, Akerman made work that bore witness to horror and somehow retained hope. In Maniac Summer (2009), multiple projections of handheld video footage illuminate three walls. One channel is large and clear; the rest are black-and-white, delayed, and oversaturated—you might see Akerman’s face and then a trailing puzzle of fragmentary visual echoes. It is a chaotic work, splintered and sweltering in agitation.

The final installation, NOW (2015), was the last artwork Akerman made before her death. Its elaborate setup consists of five rear projections on Plexiglas screens, two floor projections, five mono and stereo soundtracks, fluorescent lamp tubes, and two Chinese fake aquarium lamps. The most sonically rich work in the show, NOW is a tumult of thunder, birdsong, gunshots, screams, and prayers. Akerman finished the audio before she found the images: fast-moving right-to-left tracking shots in a desert. The screens are suspended from the ceiling and viewers descend stairs to move around the work. Are you alone here? The floor shimmers like winds on a dune.

Akerman frequently cited the 40 years that Jews spent in the desert after slavery in Egypt: “The idea is sublime: taking time to shed the traces.”4 People no longer have this time or space to heal from genocide or catastrophe. This is what Akerman’s work offers. Her subjects are revealed in long takes, from a tender distance, allowing a gaze to be returned to the viewer. Devoid of figuration, the face-to-face encounter in NOW exists between viewers. Each sees the other through translucent screens, wandering through messianic time and then exiting into a new hallway.

Chantal Akerman quoted in Christine Smallwood, La Captive (Berlin: Fireflies Press, 2024), 16.

Akerman’s prospectus for the film, reprinted in Kathy Halbreich, Bruce Jenkins et al. “Bordering on Fiction: Chantal Akerman’s D’Est” (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 1995), 17.

Akerman, quoted in Marie Liénard, “Sud de Chantal Akerman ou une histoire de territoire et de terre : le Sud comme espace de mémoire”, Anglophonia Caliban/Sigma 19, 2006. http://journals.openedition.org/acs/2416

Nicole Brenez, “Chantal Akerman: The Pajama Interview,” LOLA, Issue 2. Originally published in Viennale, Useful Book #1 (2011), http://www.lolajournal.com/2/pajama.html.