Crossing the street on my way to the Yokohama Museum of Art, the phrase “Wild Grass” flashed through my mind. Suddenly, I stumbled and fell. I was back on my feet quite quickly, but not before a passerby had asked in English whether I needed help. I had tripped over a ground reflector, as if being penalized for straying too far off course, and the warning—catastrophe can strike at any time—set the tone for the exhibition ahead. With a sting in my right hand and left knee, I entered the central venue of the Yokohama Triennale.

It’s fortunate that this year’s Triennale has coincided with the reopening of Kenzō Tange’s refurbished Museum of Art, its postmodernist spirit measured by his trademark modularity. The grand entrance gallery is an architectural gem: as you enter at its transverse middle, a series of tiered platforms rises gently to the left and right, spanned by a gabled glass roof with adjustable light slats. The curators of this edition, Carol Yinghua Lu and Liu Ding, have turned this theatrical space into the multi-sensory set of a dystopian scenario. Hovering overhead are three skeletal metal frameworks covered in crisscross vermilion textile strips, like the shed shells of giant beetles. Two similar maroon-colored structures, also conceived by Sandra Mujinga (Unearthed Leaves, 2024), ascend across from the entrance, as if two Godzilla-like creatures had embraced in a deadly showdown before being turned into shadowy ghosts by a great disaster.

At the center of this constellation stands a strange four-legged figure composed of mismatched showroom dummy parts. Pippa Garner’s Human Prototype (2020) rhymes with Miles Greenberg’s similarly multi-legged sculptures (produced by a 3D printer from scans of the artist taken during a durational performance). Their queering and Afrofuturist tendencies are wonderfully complemented by the Doomsday-hoarder sentiments of Søren Aagaard’s Preppers Lab (2024), a camouflage tent featuring instructive videos alongside not-so-fun facts (“there is a place for every person in a bunker in Switzerland”). Joar Nango, on the other hand, has used solid woodworking and temporary tent structures to create a zone in which the nomadic way of life of the Scandinavian Sami literally invades the postmodern, decorative horizontal furrows of Tange’s architecture (Ávnnastit/Harvesting Material Soul, 2024).

The scene is completed by two works that are unsettling in different ways. As you approach Özgür Kar’s animated video Fallen Tree (2023/24), the unnerving sound of buzzing flies indicates that something is rotting inside a dead tree displayed on standing screens at life size. The other is Open Group’s Repeat After Me (2022), in which Ukrainian war refugees imitate the sounds of weapons.1 As alarm bells sound at irregular intervals from the galleries upstairs, the reality of an ongoing war fulfils the sense of continuous crisis mode. The atmosphere is a cross between the murky Tatooine markets of Star Wars (1977), the Orwellian grotesqueries of Terry Gilliam’s Brazil (1985), and an amateur documentary video shot in a warzone.

This elaborate opening sequence conveys a heightened awareness of the present and the surreal feeling that a catastrophic future has arrived too soon. This combination is central to Lu Xun’s poetry collection Wild Grass (1927), in the introduction to which the author emphasized pieces addressed to the political moment (namely the 1926 massacre of unarmed demonstrators on Tiananmen Square). These are, Lu writes, “small pale flowers on the edges of the neglected hell.” There is a coded, allegorical level at work here (the stubborn survival of the marginalized?2 The complacency of the powers that be?) that resonates with a present in which authoritarian and autocratic powers are on the rise again, and in which people often have to speak in riddles to be able to speak at all.

The clash between matter-of-fact and surreal continues on a circular course raised above the central gallery. A selection of Tomáš Rafa videos documenting the violent rise of the far right in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia is displayed on an angled television like in a hotel room and combined with two life-sized, 3D-printed sculptures by Josh Kline of people lying on the floor in fetal positions wrapped in clear plastic bags, titled Wrapping Things Up (Tom/ Administrator) and Thank you for your years of service (Joann/ Lawyer) (both 2016). The suggestion that white-collar workers are literally disposable waste chimes eerily with the racist and homophobic hate in Rafa’s videos—in predatory capitalism, these are two sides of the same coin.

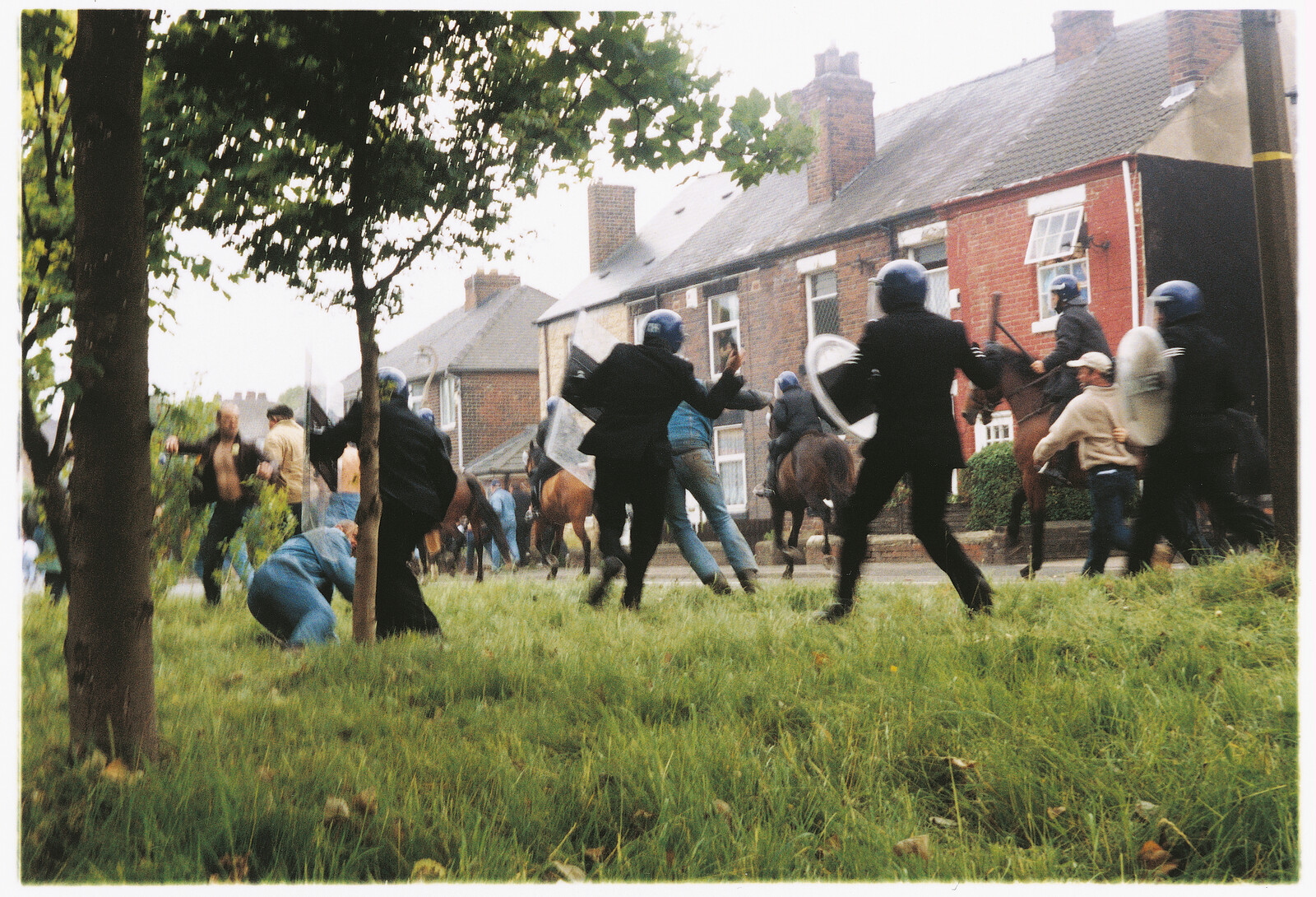

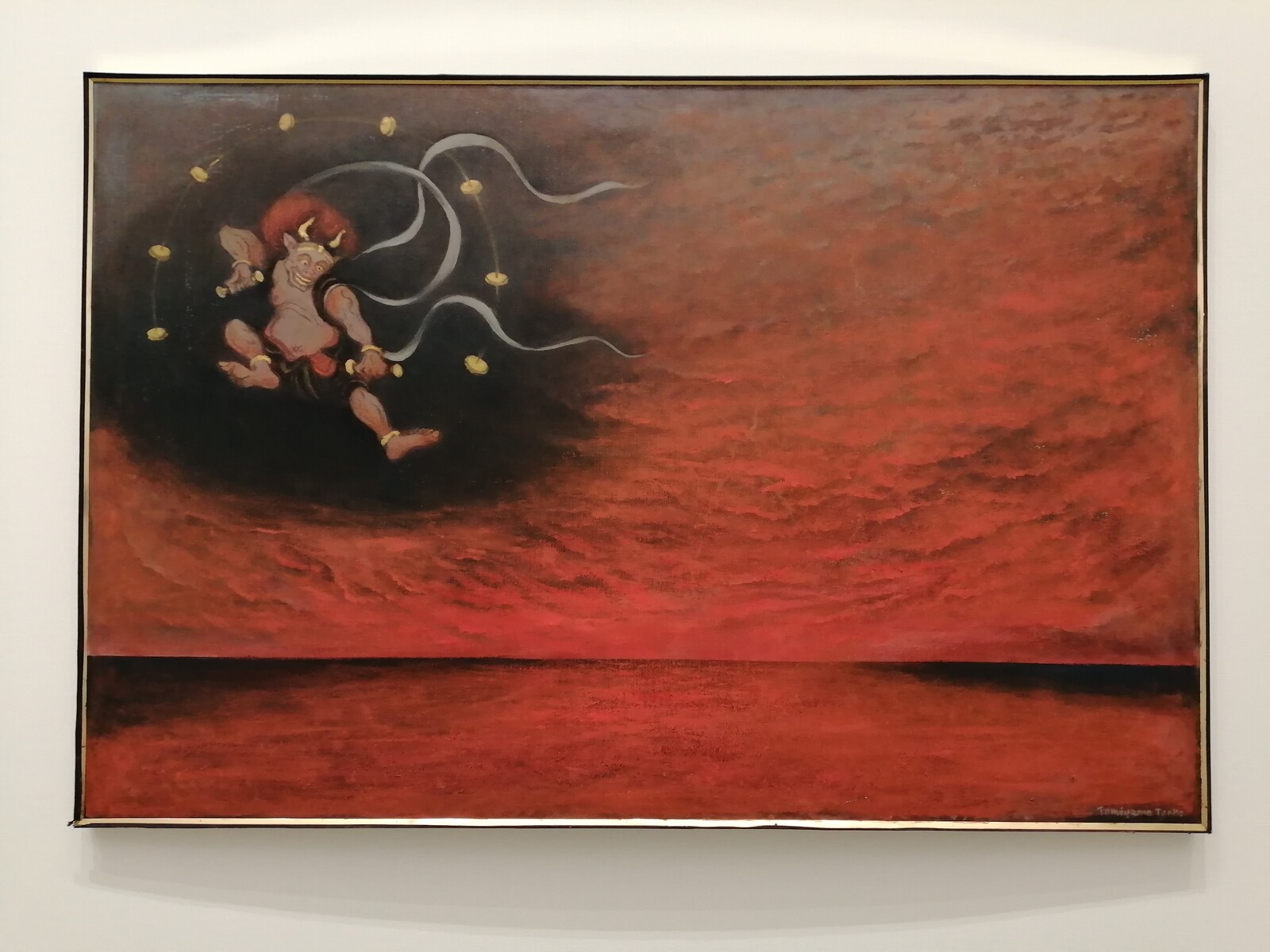

The curators boldly repeat the combination in reverse at the far end of the space, while placing Jeremy Deller’s The Battle of Orgreave (2001) smack in-between. This reenactment of a 1984 fight between the police and striking miners (with roles played by veterans of the original confrontation) challenges Margaret Thatcher’s credo that “there is no such thing as society” by celebrating solidarity and resistance through swagger and grim humor. The curators delve deeper into the history of protest and workers’ struggle with a mini-retrospective of Taeko Tomiyama (1921–2021), whose 1946 painting Ruins transfigured the destruction of Japanese cities in World War II into the chilling sublime of ancient temples. Later she channeled the shock of the Fukushima nuclear disaster into sardonic paintings in which demons dance over a blood-red sky (Crisis: Prayer for the Sea and Sky, 2012) or ride a pink cloud (Fukushima: Spring of Caesium-137, 2011).

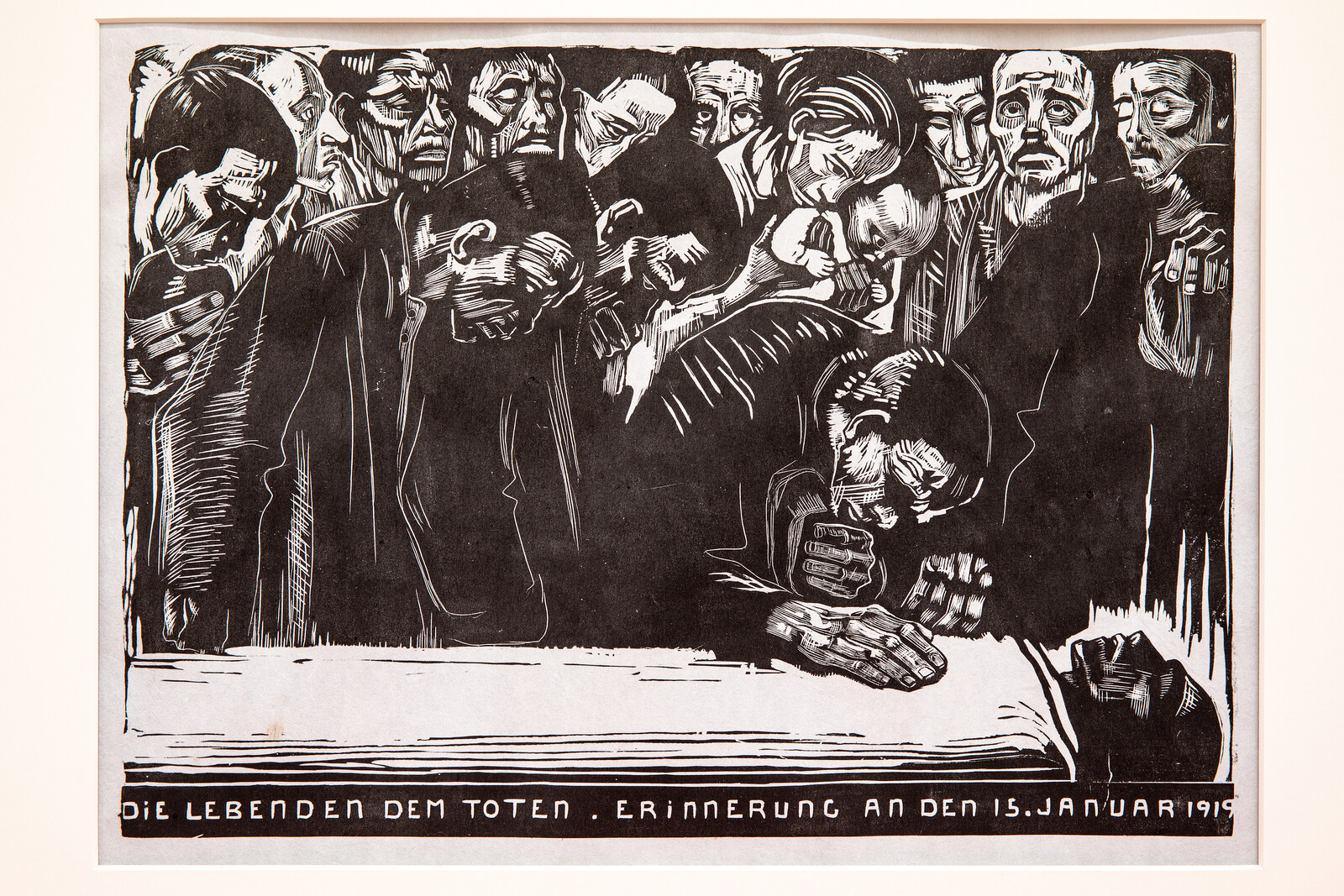

In the early 1960s, Tomiyama followed Japanese miners who emigrated to South America after losing a labor dispute. That her watercolor-and-ink portraits of these miners seemed eerily reminiscent of Käthe Kollwitz was an association I attributed to my German eyes, only then to encounter Kollwitz’s dense woodcut In Memoriam Karl Liebknecht (1919–20) later in the exhibition. As it turns out, Lu Xun was a collector and publisher of Kollwitz’s prints, contributing to the renaissance of Chinese as well as Japanese woodcut printing in the 1930s and ’40s. Documentary sections are dedicated to the way that progressive circles used these cheaply reproducible images, with their stark black-and-white aesthetics, to communicate with the masses. If the curatorial loose ends don’t always join up—as when such a documentary section jars with a mini-retrospective of the prankster artist and musician Xper.Xr featuring works called Mechanical Toy Cat (2002) and Adhesive Chest Hair (2000)—then the desire to tie things up neatly might run counter to the theme of “Wild Grass.”

The aforementioned alarm bells turn out to be a work by Atsuko Tanaka, who was part of the pioneering Gutai movement. Entitled Work (Bell) (1955/1981), it involves an instruction to press a button that sets a line of bells ringing in sequence. In this case, my eyes follow the line to a video of Klara Lidén walking through New York’s financial district in an uninterrupted shot, like in a 1990s pop video by Massive Attack or The Verve. They fall down and stand up again, carrying on as if nothing had happened (Grounding, 2018). I did it once, Lidén does it numerous times, turning Bas Jan Ader’s melancholic fall into an uncanny mission to continue functioning. The last shot features the portico façade of the New York Stock Exchange, letting the brutal ups and downs of financial capitalism become apparent as something that forces itself onto art, artist, and work.

The Triennale’s other venues continue to respond to Lu Xun’s Wild Grass and its allegorical exploration of the connection between political upheaval and surrealist imagination. One striking juxtaposition is the display of several artist collectives in the 1920s-era cash-desk hall of a former bank. The Guangzhou-based Energy Waving Collective use activities—ranging from outdoor gatherings disguised as kung fu practice to the publication of a zine—to approach issues that cannot be discussed directly under conditions of censorship. Not the least of which is the difficulty of establishing informal, self-governing collectives in China. Hajime Matsumoto and Hikaru Yamashita, meanwhile, are key figures in the Amateur Riot (Shiroto no Ran) movement that formed to foreground the precarious situation of youth in Japan’s stagnating economy and was later among the first to organize protests after Fukushima. In recent years, Matsumoto has channeled his energies into forming a network of Asian underground collectives, towards—as he is quoted in a text panel—“creating post-revolutionary worlds ahead of time.”

One might grumble that these are not new phenomena. But since Amateur Riot and the Occupy movement of the 2010s, “grassroots” protest movements have often seemed unwilling to confront the basic economic structures underlying repressive social conditions. Worse, they have sometimes plunged into conspiracy theories rather than make enquiries into the deeper sources of the problems they identify. But maybe that is the point being made by this Yokohama Triennale: the “wild grass” that grows over, and under, supra-structural factors from climate to capitalism needs to be combed through now and again.

Editors‘ note; For more on this work, see Jörg Heiser, “The National Pavilions at the 60th Venice Biennale,” e-flux Criticism: https://www.e-flux.com/criticism/606882/60th-venice-biennale-national-pavilions.

Lu Xun, Wild Grass (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1974), 2. He also writes, “I love my wild grass, but I detest the ground which decks itself with wild grass.” (Ibid, 3.)