September 19–October 13, 2024

A hard rain had been falling the week before the opening of Steirischer Herbst, the annual art festival in the Austrian city of Graz. The river running through the Styrian capital was wild with uprooted trees after floods that, in northern Austria, left five dead. The catastrophe took on greater significance given that it coincided with the run-up to the general election on September 29, the polls for which are led by the far-right populist Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ.) and its brazen climate change denialism. Riffing on the Lord’s Prayer, their billboard address to the electorate—Euer Wille geschehe (Your will be done)—looked less enticing submerged in brown floodwater.

And so the billboard project by Vienna-based Yoshinori Niwa got off to a perfect start, having appeared two days before the opening in the center of town. As I walked by, I observed a police officer on her walkie-talkie, anxiously awaiting instructions. The nervousness was caused by Niwa’s parody of a FPÖ. election poster, in which an “EPÖ.” party announces Jedem das Unsere (To Each Our Own, playing on the infamous slogan at the entrance to Buchenwald concentration camp) and candidate “Dr. Steinapfel” holds a bratwurst to his ear. The poster was covered with tarpaulin until the public prosecutor’s office dropped an absurd allegation (apparently made by an irate call to police station) that the work constituted Nazi agitation, providing the FPÖ. with an excuse to call for the withdrawal of funding for Steirischer Herbst. The temporary covering-up of the billboard ironically anticipated a performative erasure of the image, manually enacted by the artist daily, as instructed by the work’s title: Cleaning a Poster During the Election Period Until It Is No Longer Legible (2024).

Steirischer Herbst, founded in 1968 and directed by Ekaterina Degot since 2018, can count a series of similar incidents in its history: in 1981, a Neo-Nazi dumped a cartload of manure in front of a Hermann Nitsch exhibition; in 1988, Hans Haacke’s restaged National Socialist-monument in a public square titled Und Ihr habt doch gesiegt (And yet you won) was burned to the ground. In 1998, Christoph Schlingensief, with his announcement that he planned to “bring as many homeless people as possible to Graz,” caused outrage among the local FPÖ., whose indignant protest letter he promptly used for the official booklet. Niwa’s approach is rather gentle by comparison, yet resonates with the title of this year’s edition: “Horror Patriae,” horror of the fatherland.

The eponymous exhibition at Neue Galerie forms the centerpiece. The first object you encounter on entering is the plaster-cast fragment of a fountain figure: a plump cherub with a rather Wagnerian forehead struggling with a serpent. It’s an undated work by Gustinus Ambrosi, who made a bust of Mussolini in 1924, was commissioned by Albert Speer to design the fountains for Hitler’s Reich Chancellery, and who continued to have a robust career in Austria until his death, in 1975, when he was buried in a “grave of honor” (a distinction granted to citizens of which the city is proud) in Graz. Like numerous other pieces in the show, it comes from the collection of Graz’s Universalmuseum Joanneum, of which Neue Galerie is a part.

Degot and her curatorial team (David Riff, Pieternel Vermoortel, and Gábor Thury) must have enjoyed, albeit with a shudder, plunging into this collection, bringing to the surface evidence of a modern art history tinged with nationalist and ethnicist ideologies: horror patriae indeed. They juxtapose their finds with contemporary work—the friction certainly benefitting the latter, while the horrors of “fatherland” continue into the present. Ambrosi is satirized by sculptures of the traditional lederhosen and dirndl constructed out of steel and filled by a sack of white concrete (Michèle Pagel’s White Trash Bag #1 (Firstborn Male Descendent), and White Trash Bag #2 (Infanta), both works 2023).

Alfred Schrötter von Kristelli’s Heimaterde [Native soil] (1916) depicts an Austrian peasant couple—he behind the plough, she leading the horse and oxen—from the perspective of the topsoil. Their faces are strained, determined, serious. It is the painterly visualization, in an academic style with Ferdinand Hodler undertones, of the “blood and soil” ideology that imagines a connection between the land and a racially uniform Volkskörper. The contemporary pieces work like antidotes to these exhibits, often through parody or sardonic commentary, successfully in the case of two short videos by Alina Kleytman. The Tongue (2020) shows the artist in a hospital bed, her tongue swelling to monstrous proportions; in The Place to See Before You Die (2024) a dashing male voiceover, in the style of a promotional video, promises an exceptional tourist experience in the artist’s home city of Kharkiv, Ukraine. Destroyed apartments and new cemeteries are praised as sightseeing locations by a shamanic figure somewhat resembling the Joker.

A life-sized wooden puppet in white linen dress represents a “Slawin in Urtracht” (Slavic woman in ur-traditional gown), suggesting primitive backwardness. It is lifted from an ensemble on display at Graz’s Volkskundemuseum conceived by Viktor Geramb, who started work on a Trachtensaal (hall of traditional gowns) in 1936, and finished it in the summer of 1938, just after the annexation of Austria by Germany. The mannequins at Volkskundemuseum—wearing shepherd’s hats or medieval cloaks, with oversized wooden heads and staring eyes—are sinister in a way that would have made Mike Kelley whoop. To be fair, the museum staff are aware of the ideological underpinnings of these figurines, and the bylines clearly indicate their “ethnic stereotyping” and the Nazi connections of some among the artisans involved in making them.

Back at the Neue Galerie, a series of photographs of Thomas Bernhard’s traditional farmhouse—with rustic furnishings installed in a cool and functional style—is described by the wall label as showing “another side” to the famously sarcastic and anti-nationalist writer only revealed after his death, in 1989. However, this rural home was a notorious aspect of Bernhard’s eccentric theatricality during his lifetime, and hardly a secret: “My farmhouse hides what I do,” he wrote for Die Presse in 1965. “I walled it up, I walled myself in. And rightly so. My farmhouse protects me. If it is unbearable for me, I run, I drive away, because the world is open to me.” This is a pitfall of the contemporary artworld’s probing into art-historical, anthropological or, as in this case, literary realms: it’s easy to gesture at debunking where those (at least indirectly) addressed have, in fact, long since done the critical work themselves.

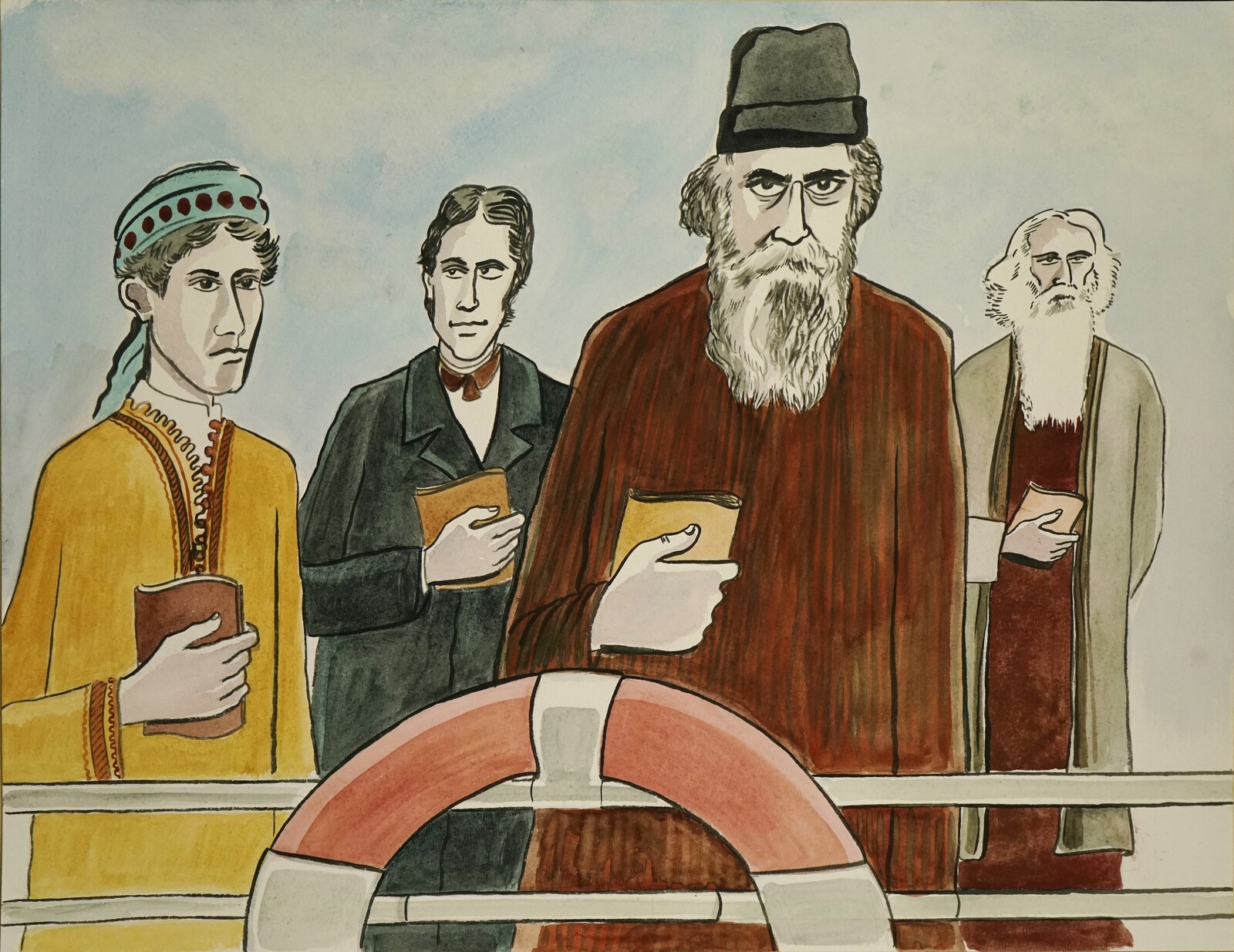

Yet some of the artists commissioned to make new work—notably Sarnath Banerjee and Jan Peter Hammer—manage to explore questions of ideology and aesthetics with acuity, countering reductive interpretations with what could be described as double or dialectical narratives. Executed in his graphic-novel style, Banerjee tells the parallel stories of Styria’s Peter Rosegger and Bengal’s Rabindranath Tagore, who competed for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913 (Fathers, 2024). The differences between the two writers are as striking as are the similarities. While Rosegger came from a poor family with little access to education and Tagore was the scion of a wealthy family pushed through elite schooling (the conventions of which he despised), both championed rural stories and songs and sought to strengthen the rights of peasants (when Tagore won the Nobel, the Austrian press howled foul). Using just a stripped-down series of text and image sheets, Banerjee evokes an era without reproducing its clichés.

Hammer explores the ideological construction of soil and Volkskörper with his video Noreia (2024). In 1930, the Styrian archeologist Walter Schmid claimed to have found remnants of a Celtic settlement dating from their victory, in 113 BCE, over Roman legions. Schmid’s findings made inhabitants of the nearby Sankt Margarethen village proud, and Styrian Pan-Germanists were electrified by this alleged evidence for ethno-Germanic, indigenous “roots.” The village was renamed Noreia, after the legendary lost Celtic city that Schmid claimed to have found. After the war, the claim was refuted—the ruins turned out to be medieval—yet the myth persists, and today locals re-enact Celtic fantasies as archeologists question the ideological history of their own profession. Filming the protagonists, Hammer captures the tension between them with unpreachy subtlety.

Degot and her team, similarly, evoke the specter of nationalism without resorting to obtrusive didactics. In doing so, they respond not only to the ascent of the far-right but also to those in the art world who in recent years have, under the auspices of acknowledging non-European cultural practices, sought to replace the idea of a sort of rhizomatic cosmopolitanism with longing for the “soil” and “ancestry.” In doing so, they often ignore the susceptibility of these concepts to the kind of false (re-)appropriation to which this exhibition is so alert.

Two performance commissions stood out as counter-arguments to these tendencies. The Phantom of the Operetta (2024), by transnational ensemble La Fleur, is a ninety-minute tour de force through the life and work of Emmerich Kálmán, the Hungarian Jewish composer of The Csárdás Princess (1915), who fled Vienna to the US in the wake of the Anschluss. Performers from France, Mexico, and Côte d’Ivoire probe the story and its contradictions through eloquent dancing and singing—interspersing Waltzes and Charlestons with Legwork and Amapiano, chamber strings with percussion and electronic beats—infusing the history of Jewish-queer operetta with decolonial elasticity.

Also shattering fantasies of unity and unambiguity by enacting contradictions was Augustin Maurs’s Out of Tune: Favorite Songs of Dictators and Political Leaders (2024). At the variety theater venue Orpheum, Maurs, accompanied by piano and drums, crooned his way through a bloodcurdling Worst Of, of the preferred songs of autocrats and populists, ranging from Silvio Berlusconi’s “Meglio ‘na canzone” through Mao Zedong’s “Awaara Hoon”—a Bollywood evergreen—to Donald Trump’s surprisingly meaningful “Is That All There Is?”

Maurs’s point was not sardonically to heighten the thrill of the transgressive, but to resuscitate music strangled by dictatorial sentimentality. Especially chilling were his renditions of Hitler’s beloved “Blutrote Rosen” [Bloodred roses] (1929), singing it in increasingly higher and more haunting transpositions, and Frank Sinatra’s “My Way,” sung to jarring twelve-tone chords in reference to Slobodan Milošević’s embrace of the song in the run-up to his trial for crimes against humanity and genocide at The Hague. Maurs’s song cycle set the tone for “Horror Patriae”: you can’t have the cake and eat it, or rather, you can’t confront the horror without allowing it to chill you to the bone.