This is the second part of an essay by R.H. Lossin on the relationship between art, artificial intelligence, and emerging forms of hegemony. The first instalment was published on January 17 and can be accessed here.

Rashaad Newsome debuted “social humanoid artificial intelligence” Being at LACMA in 2019. The “robotic griot” (pronouns they/them) initially functioned as a guide to gallery visitors, and was designed “with agency in mind.” This meant that Being, unlike most service employees, wouldn’t respond predictably to user demands, but instead could “go rogue.” Other iterations of Being, trained on different data, have offered culturally sensitive app-based therapy to address experiences of racism, and led decolonial workshops.1 The major political claim made by Being is that it is an AI trained on a “counterhegemonic” dataset made up of “alternate histories and archives such as abolitionist, queer, and feminist texts” by Paulo Freire, Cornel West, bell hooks, and others. The dataset is organized using “non-Western indexing methods” (although it is unclear exactly what this means in relation to texts written in English and Portuguese).

Being is visually represented in a humanoid animation whose movements were partly derived from “the gestures and movements of vogue practitioners proficient in styles ranging from Old Way to Vogue Femme and all their subsets.” This gives the robotic androgyne a distinct presence and a physical grammar drawn from a queer subculture: the idea was not just to add value to Being, but to create an archive of Voguing styles.2 The value to future researchers is yet to be determined, but for the moment Being is able to dance and move in a manner that clearly signifies queerness to a broad audience. This should, so the logic goes, allow Being’s machine knowledge to operate with an anti-racist, feminist logic in a queer form.

The liberal impulse to redress historic wrongs by progressively expanding the public sphere is nothing to scoff at. There couldn’t be a better time for marxists to climb down and admit the social value of including someone other than white heterosexuals in public discourse and cultural production. That said, counterhegemonic generative AI is a fantasy even if you define the diversification of therapy as counterhegemonic. In addition to causing disproportionate environmental harm, these elaborate experiments with computer subjectivity are always an exercise in labor exploitation and colonial domination. Materially, they are dependent on the maintenance and expansion of the extractive arrangements established by colonialism and the ongoing concentration of wealth and intellectual resources in the hands of very few men; ideologically they require increasing alienation and the elimination of difference. At best, these experiments offer us a pale reflection of intellectual engagement and collective social life. At worst, they contribute to the destruction of diverse communities and the very conditions for the solidarity required for real resistance.

Created by Rashaad Newsome, Being is a digital griot who functions as a performance artist, poet, educator and healer. Photo by Rashaad Newsome Studio.

I want to make clear that this essay is not a personal criticism of Newsome or a general dismissal of his practice. This essay originally included a number of other similar works, but Being was distinguished both by its political ambition and by the fact that so much of Newsome’s other work is concerned with reproducing counterhegemonic practices by supporting the social relationships that make resistance possible. The film Assembly (2025), which documents the seven-year, international collaboration that led to Newsome’s Armory show, presents art as a model of solidarity-building rather than an object to be consumed. It foregrounds the many forms of labor required for the production of anything significant and meaningful.3 The perversity of Being lies in its erasure of precisely these relationships; the mystification of the labor of dance, resistance, love, and survival that is documented by the performances and objects that surround and support the digital griot.

Attempts “to understand life by reproducing it in machinery” are not new.4 Automata can be dated back to antiquity, and the mythological record suggests that the existence of these mechanical sleights-of-hand produced fantasies of near-human or super-human machines remarkably similar to our own.5 During the eighteenth century, at the dawn of the first industrial revolution, “self-moving machines” became more than demonstrations of technical virtuosity, and their storied enchantment by gods and sorceresses was subsumed by new and fascinating scientific advances. Modern automata aspired to the status of experiments. They captured the public imagination by being lifelike. Being like a living thing, even claiming to be like a living thing, raised questions about what it meant to be alive. Jessica Riskin argues that, historically, imitations of life have made two distinct and contradictory claims at once: “that living creatures [are] essentially machines and that living creatures [are] the antithesis of machines.”6

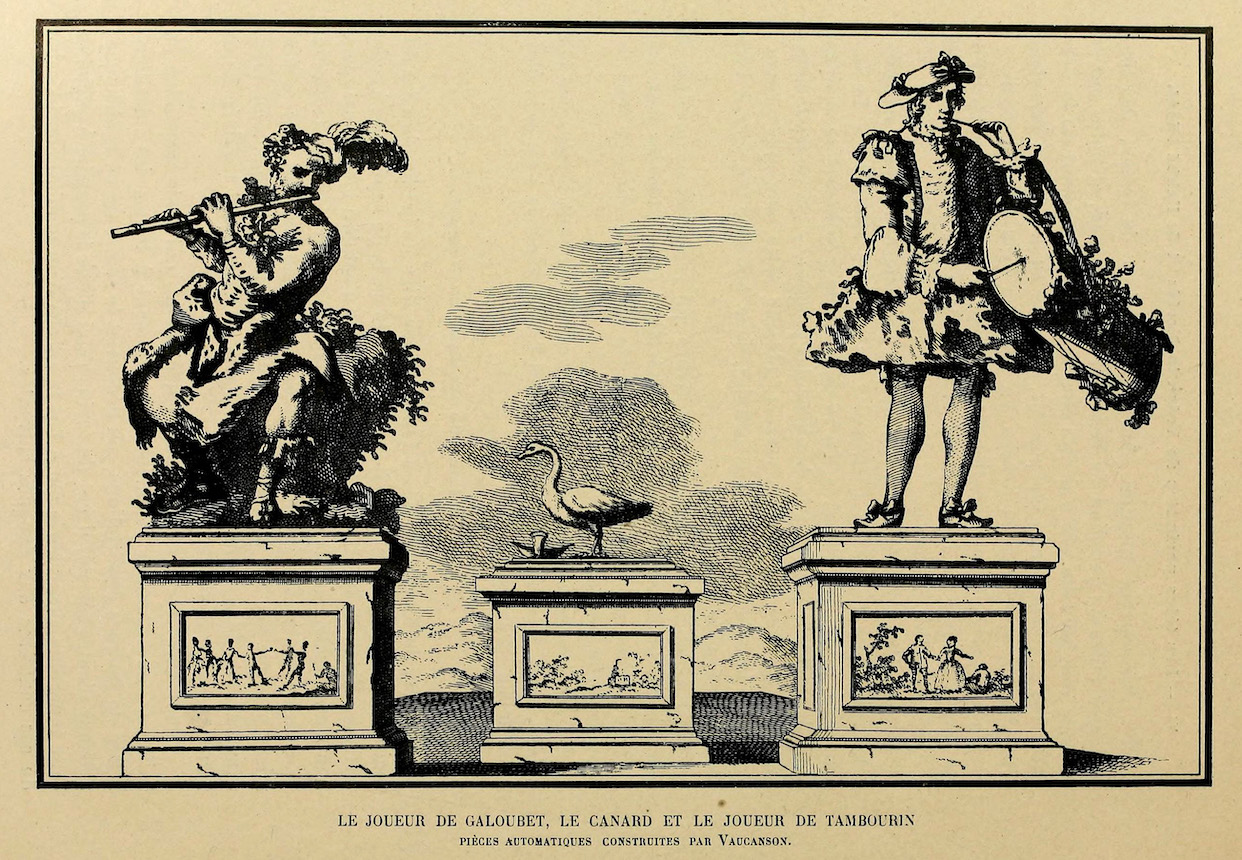

One of the eighteenth century’s most famous automata was a shitting duck. The cost for a ticket to this performance was about a week’s wages for the average worker. People turned out in droves to watch this mechanical creature consume corn and grain and expel a convincing imitation of excrement.7 Something so easily explained hardly seems to pose serious philosophical questions about life and agency and consciousness, but the demonstration that the duck had insides—that it could, through the proper arrangement of gears, do one of the things universal to animals—was a significant claim. It not only suggested that more springs and gears might produce a duck that can do two or three or four things that its living counterpart did, it also produced a teleology. It ordered the very notion of technological progress around its relative ability to imitate life. And, in self-reinforcing fashion, the ability to imitate life signified technological progress.

Illustration from Henry René d' Allemagne’s Histoire des jouets [History of Toys] (Paris: Hachette, 1902). Public domain.

Being is an impressive creation. Its sentences are grammatically sound and its intonations human enough. Its responses to its interlocutors during “decolonization workshops” are polished, lacking any of the tonal irregularities and glitchy rhythms associated with robotic speech. Its movements are fluid and unrepetitive. Formally, it puts on a very good show. But what Being says is a different matter entirely. The content of its speech is anything but the imaginative synthesis of the writing that has been used for its mechanical education. Instead, the replies are generic and applicable to almost anything that might be presented in a quasi-therapeutic setting. “Thank you,” it tells a woman who has just read a long, thoughtful reflection on the belief that financial success will protect her from the racist, patriarchal systems that she is daily reproducing through her workaholism, “for uncovering your story with your own voice and liberating your body from continued silence. There’s a place for you here and for you to find your greatest sense of freedom.”

The reason why it sounds more like an enlightened, twenty-first-century fortune cookie and less like a revolutionary feminist is because a scrambled average of the texts produced by Cornel West and bell hooks, or the taxonomy assigned to these writings, is not a text by either Cornel West or bell hooks, which means that those engaging with Being are not engaging with the ideas put forth by these thinkers or one of their interpreters but with a self-multiplying taxonomy inspired by their content. However, reproducing the writing in its training set is not the point. The conceit is that Being has learned from these thinkers and is producing original insights. Technically this is true. The word combinations are new. This sporadically convincing but impoverished idea of intellectual production is an almost poetic betrayal of one of its cited inputs. Being, and generative AI at large, embodies the most extreme version of what the revolutionary pedagogue Freire called the “banking model of education.” This imagines students as mere containers into which educators could deposit knowledge for later retrieval. Freire’s life work was organized around undoing this model of education, the power structures it mimicked, and the form of consciousness and intellect that it assumed and reproduced.

bell hooks remembers her all-Black school as a place where she was taught by women who knew her and her family, who “worked with and for” students who showed intellectual promise because they understood what they were doing—educating young Black people—as part of an anti-colonial and anti-racist project. Desegregation meant transferring to a racist white school where “knowledge was suddenly about information only. It had no relation to how one lived, behaved. It was no longer connected to antiracist struggle.”8 Attempts to improve AI with a more politically evolved dataset must conspicuously ignore the social lives, community connections, personal investments, and real historical struggles that are the stuff of politics and change. To claim that Being “discusses” challenging subjects, such as “art historical erasure, the social implications of artificial intelligence regarding rights, liberties, labor, and automation, the importance of the imagination as a form of liberation, and the subjectivity of body autonomy within an inherently inequitable society,” is to announce an appropriation of human experience and historical narrative at an almost unimaginable scale. Any attempt to replace this with an algorithm must actively suppress, obscure, and bypass the realities of racism and anti-racist struggle because AIs do not exist within real social relationships that are politically and geographically situated.

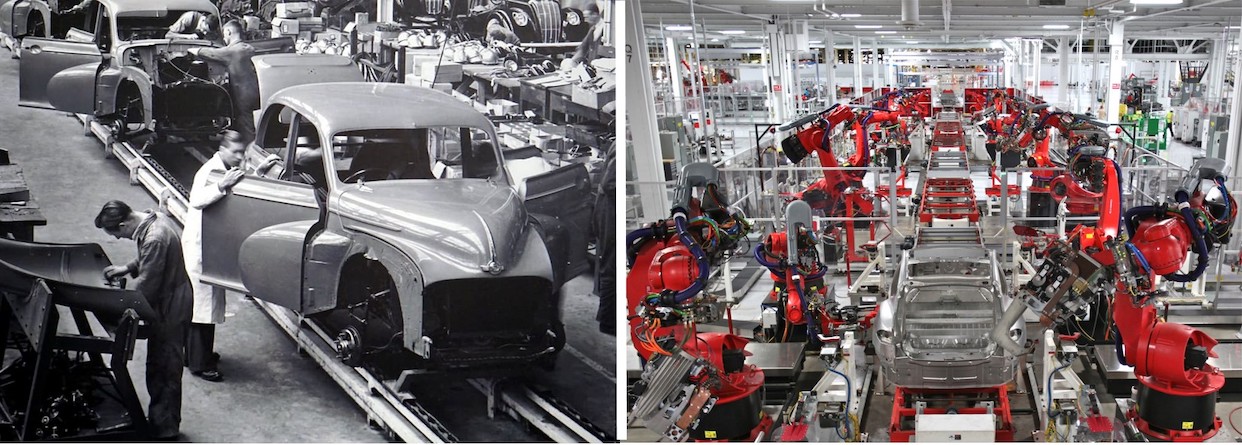

The suggestion that a self-replicating taxonomy can produce knowledge and insights generally formulated over the course of a human life seems to defy reason. But this is exactly the claim being made by artists like Newsome, the formal attributes of projects like Being, and techno-boosterism at large: that a sophisticated enough machine can replicate the most complex human creations. This is, of course, just how machine production has always worked and evolved—each generation witnessing the disappearance of a set of skills and body of knowledge thought to be uniquely human. Art making, writing, and other highly skilled intellectual endeavors are not inherently more human, precious, or worthy of preservation than any skilled manufacture subsumed by the assembly lines of the past century. In the case of generative AI and other recent developments in machine learning, though, we are witnessing both the subsumption of cultural production by machines and the enclosure of vast swathes of subjective experience. Dramatic changes to production have always been accompanied by fundamental changes in the organization of social life beyond the workplace, but this is a qualitatively different phenomenon.

“Assembly” dancers at Park Avenue Armory, performing a piece choreographed by Maleek Washington. Photo by Stephanie Berger.

The specific form of the voguing Griot is a case in point. It implies that Being shares an experience of colonial, anti-Black, and anti-queer violence. In some ways, this is an obvious deception that draws attention to the most significant and insurmountable difference between machine learning and human intelligence. That is the irreducibly human experience of an embodied, emotional reaction to social life; an impression and interpretation of one’s position within a political collective. And yet this mimetic move is powerful. Being’s visible aesthetics present an argument for the invisible software’s resemblance to an inner life that a different-looking machine would fail to make.

Humans are not like Being, but they are a crucial part of Being. In this respect as well, Being is, like any other machine, an imitation of human activity. That this activity happens to be dancing makes it more depressing, but it doesn’t change its basic structure and function. In the nineteenth century, Karl Marx observed that machinery is not just a means of production but a form of domination. In a mechanized, industrial economy, “labor appears […] as a conscious organ, scattered among the individual living workers at numerous points of the mechanical system […] as itself only a link of the system, whose unity exists not in the living workers, but rather in the living (active) machinery.” This apparent totality of machinery “confronts [the worker’s] individual, insignificant doings as a mighty organism. In machinery, objectified labor confronts living labor […] as the power which rules it.”9 Of course, Marx is referring to a workplace, not an art museum or an immersive installation, but what he is describing is precisely the experience that is encouraged by the consumption of these entertainments. It is a way to further habituate people to their role as mere links in a mechanical system. Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer described popular entertainment as a relentless repetition of the rhythms of factory production; a way for the workplace to haunt the leisure time of the off-duty worker. The consumption of generative AI as entertainment seems like another order of psychic submission.

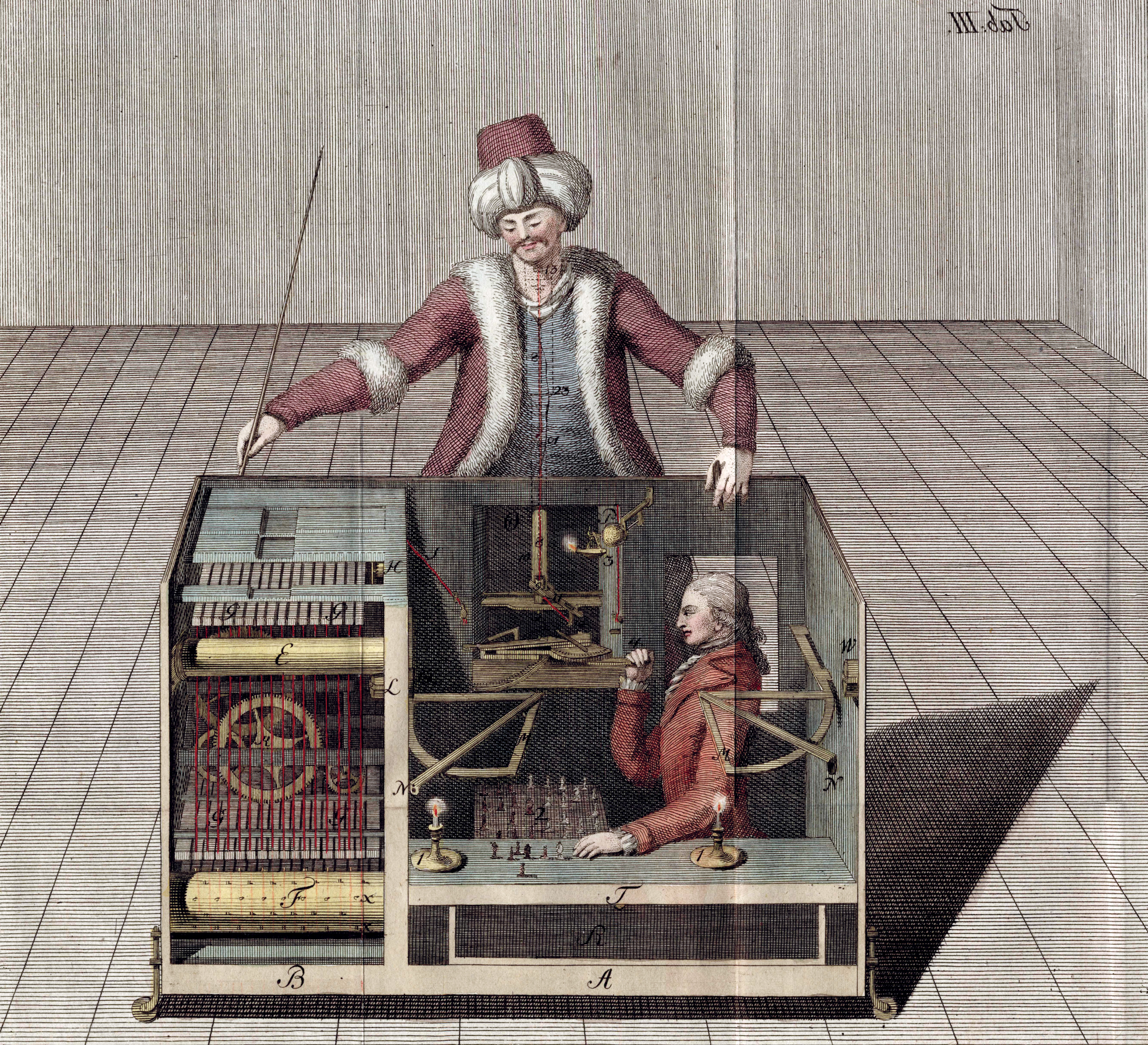

It might seem at first that Marx’s description of oppressive machinery ruling over insignificant living laborers is an experience particular to the nineteenth-century factory worker. What generative AI promises, like its predecessor “automation” is the disappearance of such drudgery and the artists collaborating with computer engineers hardly feel oppressed and dehumanized by their creations. But the labor conditions haven’t changed that much, they are simply out of sight. Hiding labor is one of the things that so-called artificial intelligence excels at. Behind most of this intelligence is a low-paid workforce tagging, transcribing, and sorting enormous amounts of data. Amazon, for example, provides “data labelling services to power machine learning models” through a crowdsourcing platform called Mechanical Turk—tellingly named after a nineteenth-century hoax that involved hiding a chess master inside of an automaton that appeared to beat people at chess.

Assembly lines. Photos by (left) Mike Bird, and (right) Steve Jurvetson. CC0 1.0 and CC BY 4.0.

Agnieszka Kurant and John Menick have used Amazon’s Mechanical Turk as a way to talk about this aspect of AI and to potentially redistribute some of the wealth produced by the artworld frenzy for NFTs and all things mechanically sentient. “Production Line” asks “turkers” to draw a straight line with a mouse that is assembled, via algorithm, into a composite drawing made up of a set number of lines and then transferred to paper. If the ink drawing is sold, the payment is distributed among the anonymous authors. This redistributive model of art making could, and probably should, be applied to many, low-tech mediums. No one makes complex objects alone. Furthermore, as feminist artists such as Mierle LAderman Ukeles have long argued (and as Newsome would almost certainly agree), it is not only the skilled fabricators but the undervalued maintenance and reproductive labor of unwaged women and low-wage, usually non-white workers that should be taken into account.10 But the formal result of this work is equally as important as its collective production: it only communicates its point about labor and so-called AI because its result is so insistently analogue. Politically, it could not make its argument in good faith in the form of an NFT or a humanoid AI programmed to draw lines like those of the workers, because formally this would recapitulate and reinforce the erasure of labor that underlies exploitation.

Much of the art produced with and about machine learning is too dazzled by its apparent capacities for human-like behavior to concern itself with the humans that it conceals and abuses. The best intentions cannot overcome the material reality of exploitation and the spectacular disappearance of labor required to maintain the participation of well-intentioned people. Generative AI, no matter how sophisticated, cannot function without this human labor and, crucially, it never will. It cannot sustain the fascinating illusion of its intelligence without concealing all of the human work and social relationships that brought something like Being into being.

The willingness of audiences to set all of this aside and to ascribe some subjectivity or consciousness to an animated algorithm may say as much about the ways that we define a person as it does about our belief in the personhood of machines. Jodi Dean argues that the capitalist subject only appears to be an individual as a result of enclosure. “Bourgeois ideology,” she writes, “treats conditions that are collective and social […] as if they were relationships specific to an individual.”11 Once “the subject is interpellated as an individual, the strengths of many become the imaginary attributes of one” and the political effects are profound.12 When the subject is restricted to an existence as an individual, agency is reduced “to individual capacity, freedom to individual condition, and property to individual possession.”13 Freud predicted that we would become miserable but powerful prosthetic “gods”; Donna Haraway, that the cyborg promised unprecedented freedom. Looking at Being should be enough to convince us otherwise. Who knows what the effects of these experimental entertainments will be, but I would wager that whatever sort of subjectivity emerges from this newest phase of exploitation as psychic extraction will be neither godlike nor free.

“Assembly” at Park Avenue Armory, New York, February 16–March 6, 2022; https://beingthedigitalgriot.com/about/; https://being-app.com.

Joel Ferree, “Rashad Newsome’s ‘Being’” Unframed (September 11, 2019), https://unframed.lacma.org/2019/09/11/rashaad-newsome’s-being.

Rashad Newsome, Assembly, https://assemblythefilm.com.

Jessica Riskin, “The Defecating Duck or the Ambiguous Origins of Artificial Life,” Critical Inquiry (2003): 612.

Adrienne Mayor, Gods and Robots: Myths, Machines, and Ancient Dreams of Technology (Princeton University Press, 2018).

Riskin, “The Defecating Duck,” 612.

Riskin, ibid.

bell hooks, Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom (New York: Routledge, 1994), 3.

Karl Marx, “The Chapter on Capital” in Grundrisse, trans. Martin Nicolaus (London: Penguin, 1973), 693.

Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Washing/Tracks/Maintenance: Outside (1973).

Jodi Dean, Crowds and Party (London and New York: Verso, 2015), 54.

Dean, Crowds and Party, 69.

Dean, Crowds and Party, 53.