It was in 2007, in the setting of e-flux’s “United Nations Plaza” in Berlin, that we first met Walid Raad and Jalal Toufic, who were working as mentors at the alternative school.1 We learned then how they conspired (or co-inspired) together, with Toufic’s texts such as “Vampires” (2003) and “The Withdrawal of Tradition against a Surpassing Disaster” (1996) complementing Raad’s construction of cultural histories under the guise of the fictional preservation foundation The Atlas Group.

So when we learned that TBA21 Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary had commissioned Raad to create a new project around the history of the Thyssen-Bornemisza collection, we were naturally eager to see it. Having sharpened the methods and approaches pioneered with Toufic, Raad has produced a highly elaborate narrative intervention into the museum’s past. Titled “Cotton Under My Feet,” this investigation was paired with a 92-minute performative tour of the museum in the company of the artist called “Two Drops Per Heartbeat,” which took place a total of 67 times in the course of the show’s run.

The intervention focused, according to the show’s curator Daniela Zyman, on the events and documents around the sale, transfer, display, storage, and conditions of a collection that became one of the largest private-public transfers of work in history when it was handed over to the Spanish state in 1993. By close attention to a set number of works in the collection, and through the insertion of his own text and photo-assemblage works, Raad points out apparently supernatural anomalies, strange coincidences, doubling effects, and intersections between his own biography and that of the Thyssen family.

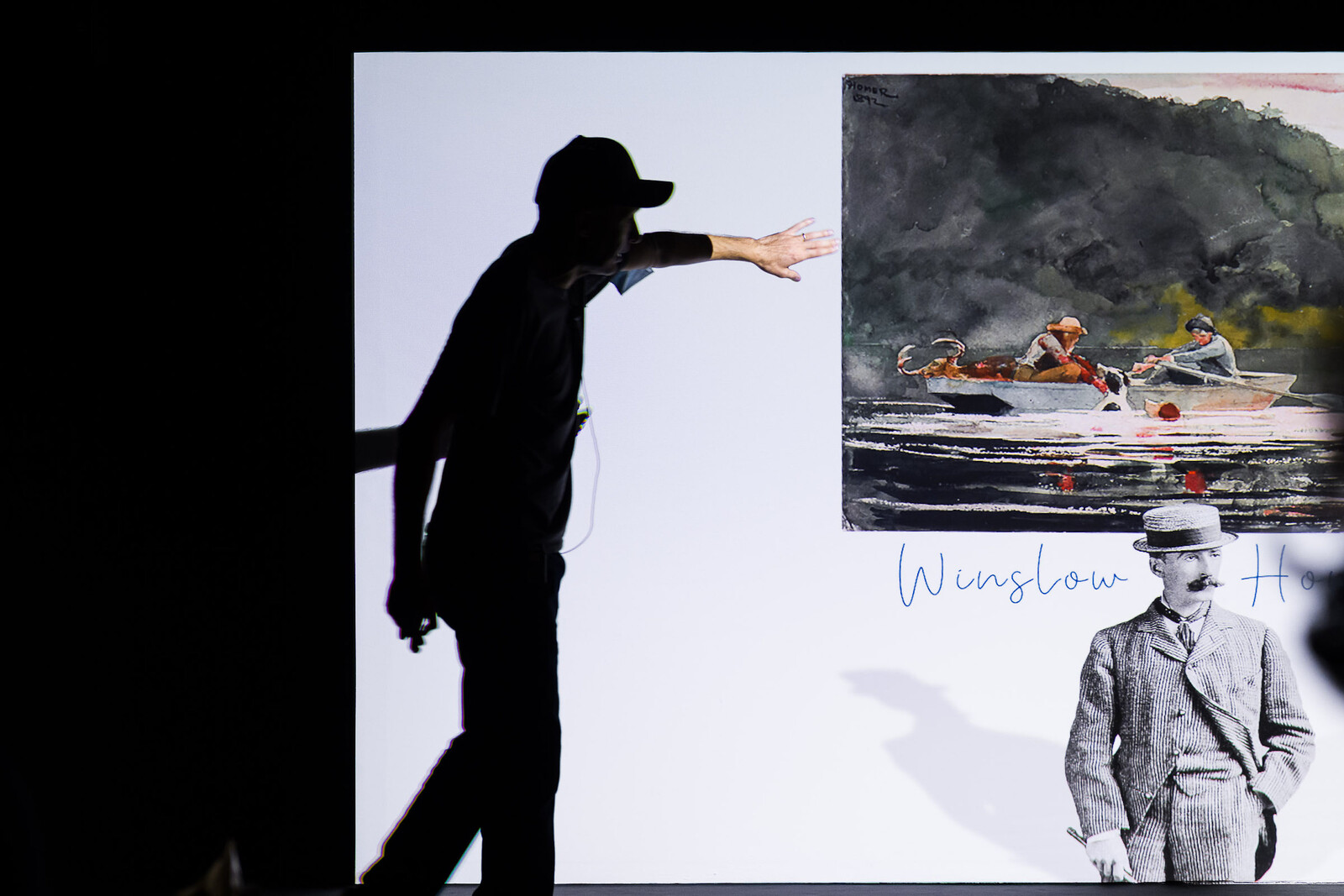

At the beginning of this “museum tour,” he offers an apologetic disclaimer: “I’m going to name many, many names, many, many numbers and many, many dates.” In typical Raad fashion, these data are superficially plausible, but one never knows (to take one example, he tells us that angels feature in the collection the same number of times as they appear in the Bible). In the course of the tour he tells a story about the collection using a cast of characters including John Constable, Abraham Lincoln, Winslow Homer, Michael Jordan, and Jamal Khashoggi.

Raad apologizes again when he insists—not for the first time—that we follow him briskly, almost running, to the next room in the museum. He apologizes because the volume of information and non-sequiturs is exhausting: the tour is mentally and physically taxing for both artist and audience. This was Raad at his most engaging, looking each audience member in the eye, almost evangelical in his wonder.

Feedback from fellow members of the audience at the end of the performance ranged from “I feel lost” to “I feel dizzy” to “I need a drink.” Though the exhibition was available to view without the tour (wall labels, as well as an audio guide and booklet, serving to relay the narrative), it is the performance that completes the project. This is art that must be experienced viva voce or, as Jalal Toufic would have it, “dead while physically alive.”

It is in that spirit—that work best experienced as discourse might best be critiqued as discourse—that we decided to conclude this text in the form of a conversation.

– Julieta Aranda and Regine Basha

Regine Basha: I found this to be Walid’s most “theatrical” performative lecture, his most physically engaging. His delivery was between that of a preacher and a carnival huckster, and compared to the subtlety of his earlier performance works, this piece felt maximalist. I wonder if that is a response to the experience of isolation.

Julieta Aranda: I found the experience exhausting. I don’t mean this in a negative way, but that I found myself being subjected to all kinds of demands throughout the lecture. As Walid narrated several decades of histories framed by the Thyssen-Bornemisza collection, as a viewer I had to surrender any attempt to parse fact from fiction, I had to empathize with the characters that were presented to me (or at least try to understand their dreams and drives), I had to keep track of intertwining timelines, memorize names and places, all the while traversing the building, catching glimpses of all the works hanging in the rooms that were external to the story being told.

RB: Were there certain rooms that did more for you than others, visually and conceptually? What did you think about the design of the itinerary itself?

JA: It was important to me to see the exhibition without Walid animating it, so as to be able to get a sense of how the works and objects placed in the space function by themselves, throughout the duration of the exhibition: are they able to carry the story? What I felt on the second visit was that the upstairs feels more like a set: like a warm-up, a stage to facilitate the suspension of disbelief, perhaps… But that was not the part of the exhibition that captured me. It was only when I was downstairs that I felt everything coming together, the echoes of stories reverberating on each other… and there I didn’t need Walid, I was completely taken by the display, the forms, the stories containing other stories.

RB: I agree that some parts of the myth-making worked more than others. Formally there were so many interpolated materials that were incongruous with the collection, that it took time to accept them. They were more like props for the performance, while the works downstairs worked on their own. But I wonder where you think this work positions itself in the discourse of decolonizing museums, repatriation, and the rendering transparent of museum stakeholders’ connection to oppressive regimes?

JA: While the exhibition concerns itself with topics that are part of decolonial discourse—it follows the stories of objects and their movements, both commercial and affective: who gave what to whom? How did a certain subject matter come about? What is the role that art objects play in the context of larger politics? What Walid does is to reclaim all the other worlds that an art object can open, beyond moral imperatives of right and wrong. The works dream, they defy logic, and they demand that I as a viewer dream right along with them. And this makes me think about how moral imperatives shouldn’t mark the limits of imagination, not even when it comes to political imagination. With Walid’s work there is always something whimsical, the possibility of magic, of a reality that exceeds comprehension. This is something to which the oppressed are always subtly denied access: the possibility to dream.

RB: But into these dreams Walid weaves political realities, as he has been doing since The Atlas Group.

JA: The weaving is extremely important. There is a lot of layering in this work, where the dreamworlds that Walid creates come alive. These are not empty dreams: they carry within themselves all kinds of freedoms and political imaginations. And I think that “weaving” has always been Walid’s modus operandi. He exposes the intricate connections between the facts and political narratives on which he grounds his work, and the fictions that he constructs around them.

The weaving makes all these threads converge into material points of supernatural density—like the gremlins in the work of Martin Johnson Heade (Gremlins in the Studio I and Gremlins in the Studio II, c. 1865–75), or the spiders (weavers themselves!), or the carpet that is heavier than its own weight. And these points of convergence are not just flourishes of fancy, they have political narratives embedded in them, of course. In that respect, as in others, the relationship between Walid and Jalal Toufic is very present in the exhibition. Can you speak about how it manifests both in the objects presented and in the performative walkthrough?

RB: It’s astonishing that these two have been in dialogue since their first meeting in 1992! I recall vividly when we were at the United Nations Plaza and they unpacked Toufic’s “Vampires” text and the theory of the undead, which now underpins this whole project so many years later.

Walid has not only internalized this text; he has, as he says, picked up where Jalal left off, concretizing these ideas through the choice of objects and the narrative that ties them together. In less capable hands, this tour could have been read as the illustration of a theory, but Walid conjures the core ideas in some ways more lucidly than the original text: in the photographs of arthropods infesting the collection objects, for example, or the dynamic of the collaborators or “co-inspirators,” and the many doubles, dyads, and twins that give structure to the narrative.

JA: I am fascinated by the way in which Walid explores the idea of the “undead,” posing it as a different spatio-temporal construct that carries ideological, economic, and political dimensions: perhaps power is undead (as in the political and economic power wielded by many of the characters that he presents us with). And that is why these characters have no regard for borders or time.

And yet I was interested to see that Walid included a personal narrative in the work. I think this is the first time that I see Walid speaking for Walid—even if it is a fictional Walid. Why do you think he made this choice?

RB: That part was kind of alarming to me, given that he has always kept himself out of the work. But it makes sense. Perhaps he anticipated the Spanish audience’s urge to know more about him and strategically embedded his personal information within an already half-truthful/half-falsified narrative. Perhaps it was a nod to the inevitability of identity politics these days? I mean, he did place cutouts of his mother and father in the same room as Yasser Arafat, Margaret Thatcher, and Magic Johnson.

JA: There is also the way he “weaves” into the collection the geopolitical histories that he has always been concerned with. He wanted to bring Palestine into the work, so he inserted his Palestinian mother, and then he created an intricate Middle Eastern narrative that converges all the way to the end, when he introduces Thomas Kaplan and Sheldon Adelson. There was this quote from Thomas Kaplan, remember? “Mythology is a wonderful thing.”

Indeed, when I looked at the cast of characters, I realized that they are overwhelmingly male. Only one female character features prominently in the story, the fictional conservator of the collection. Do you have any comments about the gender representation in the exhibition narrative, or is it not something relevant to you?

RB: In my view, he was taking down a lot of the men behind the green curtain. None of the evildoers were female. I also thought that the prominence of the conservator, Lamia Antonova, in the dialogue felt like a specter of the Jalal Toufic/Walid Raad dialogue. It left me feeling like there was a large feminine presence in the room. But ultimately, Lamia was all mysticism with no body (except for an image of her book, and a small photo purporting to be of her in the catalogue), which lent the project something like a nineteenth-century, spiritualist aura. She has a different kind of power, more in line with the labyrinth… so that does make me wonder about your point. I want to sit with it more.

Walid Raad’s “Cotton Under My Feet” was presented by TBA21 Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid from October 6, 2021 to January 23, 2022.

United Nations Plaza archive https://www.unitednationsplaza.org/.