How are stories told? Who is remembered, who forgotten, and why? Which narratives last and what histories remain unaccounted for? These are questions of the moment, when representation is crucial to political struggle and debates on decolonial knowledge gain mainstream traction. Tavares Strachan’s exhibition at Marian Goodman suggests that what was neglected was always in plain sight, and that what was missing from the narrative was often not image-making but storytelling.

A large, leather-bound and gilded book is displayed in a mahogany and glass case. Titled The Encyclopedia of Invisibility (Mahogany #9) (2018), it is part of an ongoing project that has featured in different iterations in several of Strachan’s previous exhibitions: its thousands of pages include entries dedicated to people, places, and events that were omitted from the Encyclopaedia Britannica, that is, systemically sidelined by Western history. At the most recent Venice Biennale, he displayed another version of the work, subtitled White (also 2018), along with pieces dedicated to Robert Henry Lawrence Jr., the first African American astronaut, who died in a training accident in 1967. “In Plain Sight” departs from another African American explorer: Matthew Henson, who was part of an expedition with Robert Peary and four Inuits who claimed to have reached the North Pole in 1909 (later research showed they missed it by about 60 miles).

Strachan’s Encyclopedia is surrounded by 1,354 panels, titled EIGHTEEN NINETY (2020), made in UV ink, vinyl, oil stick, and collage. Each panel, about the size of an A4 page, is encased in a clear box and includes a page from Strachan’s encyclopedia, superimposed with collaged images of classical sculptures, handwriting, scientific diagrams, and other symbols. Further up, the printed text and writing fade into an image of a galaxy encasing the top of the walls. The Enlightenment idea of the encyclopedia as a neutral, inclusive repository of the knowledge of man is rejected on all levels here: by adopting the form while revising and annotating the content, and finally allowing it to dissolve into an image. History is alive, this work suggests, its telling an active process of addition and consideration.

Then there is singing. From the stairs leading to the top-floor gallery comes a man’s baritone. He is joined by two women, who come out of two rooms hidden in the sides of the gallery where EIGHTEEN NINETY is displayed. In one, the man reads to the young woman about Henson. She listens, but also insists; she keeps correcting the book. When he reads “Eskimo” she overtakes him, saying, “Inuit.” It becomes unclear who is telling which story to whom, or at least, who is insisting on which history. The other woman, wearing a white lab coat, sings about HeLa cells. Henrietta Lacks—the African-American woman whose cancer cells were taken without her or her family’s consent and have been used in research since her death aged 31 in 1951—also makes an appearance in the upstairs gallery. Distant Relatives (Henrietta Lacks) (all works in this series 2020) combines a Kifwebe Song Mask from the Democratic Republic of Congo with a plaster, brass, and acrylic pedestal. It’s one of twelve sculptures dedicated to different men and women that bring together African masks (attributed to the place from where they were taken) with plaster portraits. In Distant Relatives (James Baldwin), a plaster portrait of Baldwin is linked with a brass pole to a Bambara Mask from West Africa, while Distant Relatives (Andrea Motley Crabtree), dedicated to the first female US Army deep-sea diver, shows a face inside the diving gear.

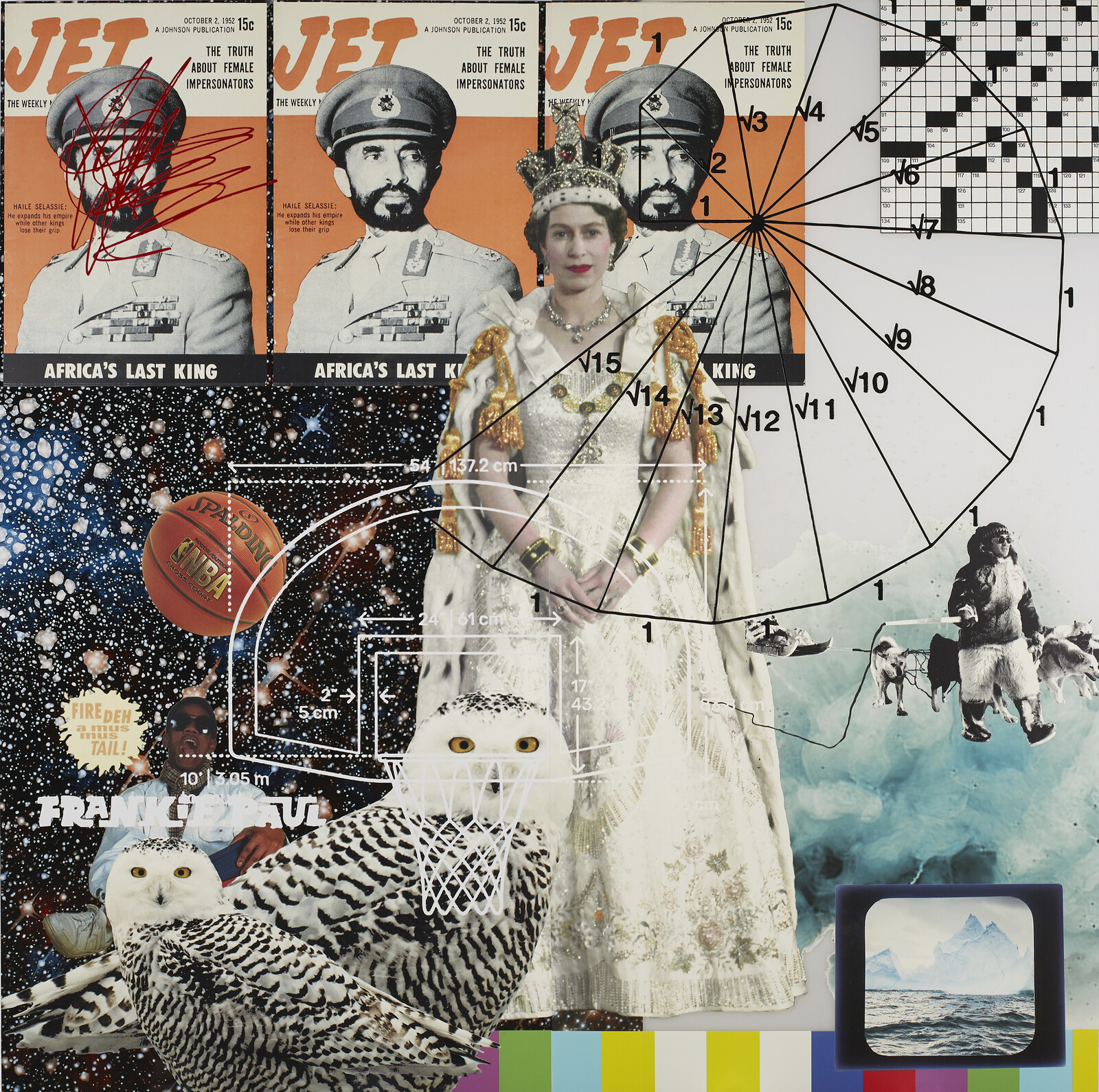

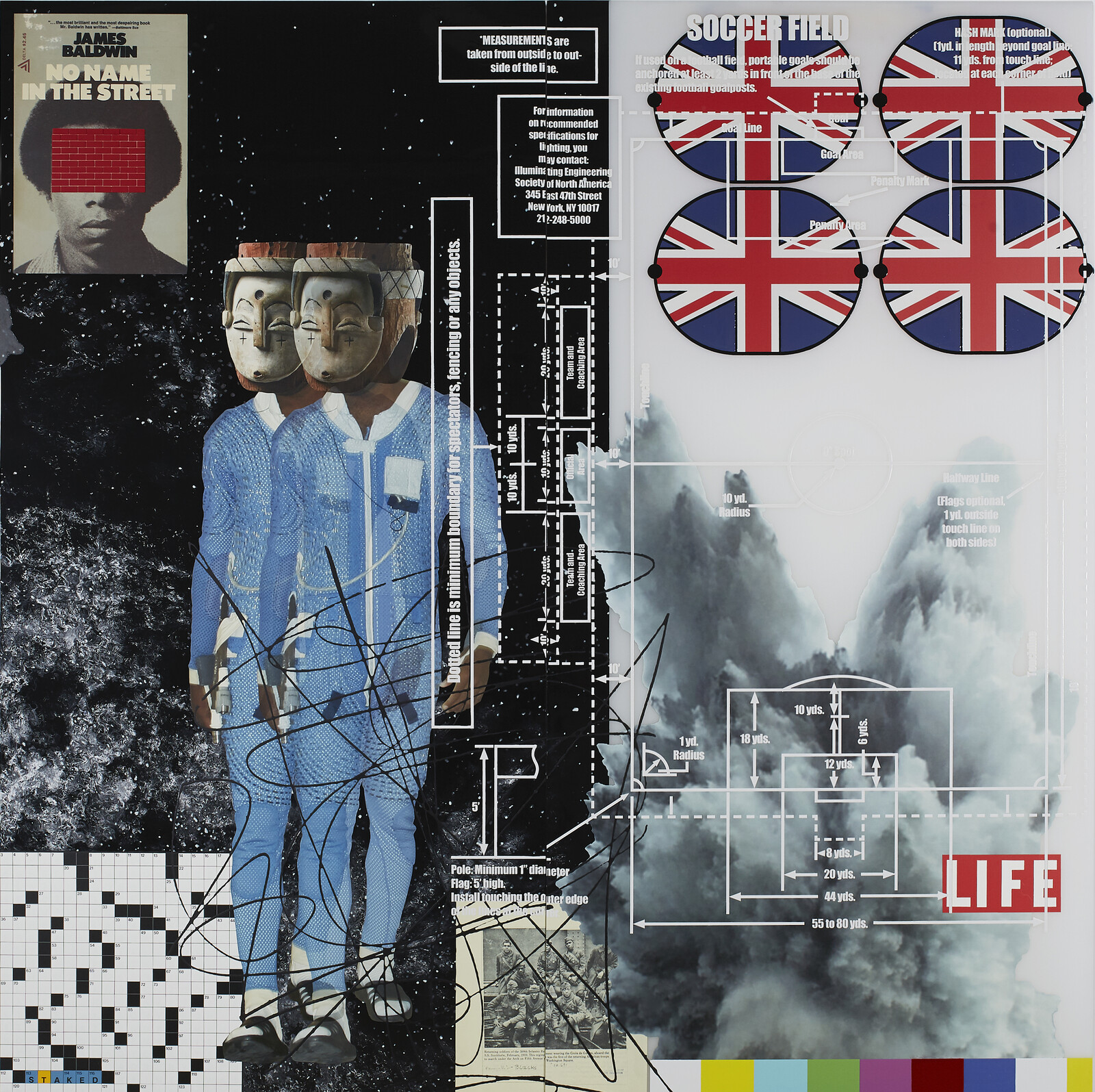

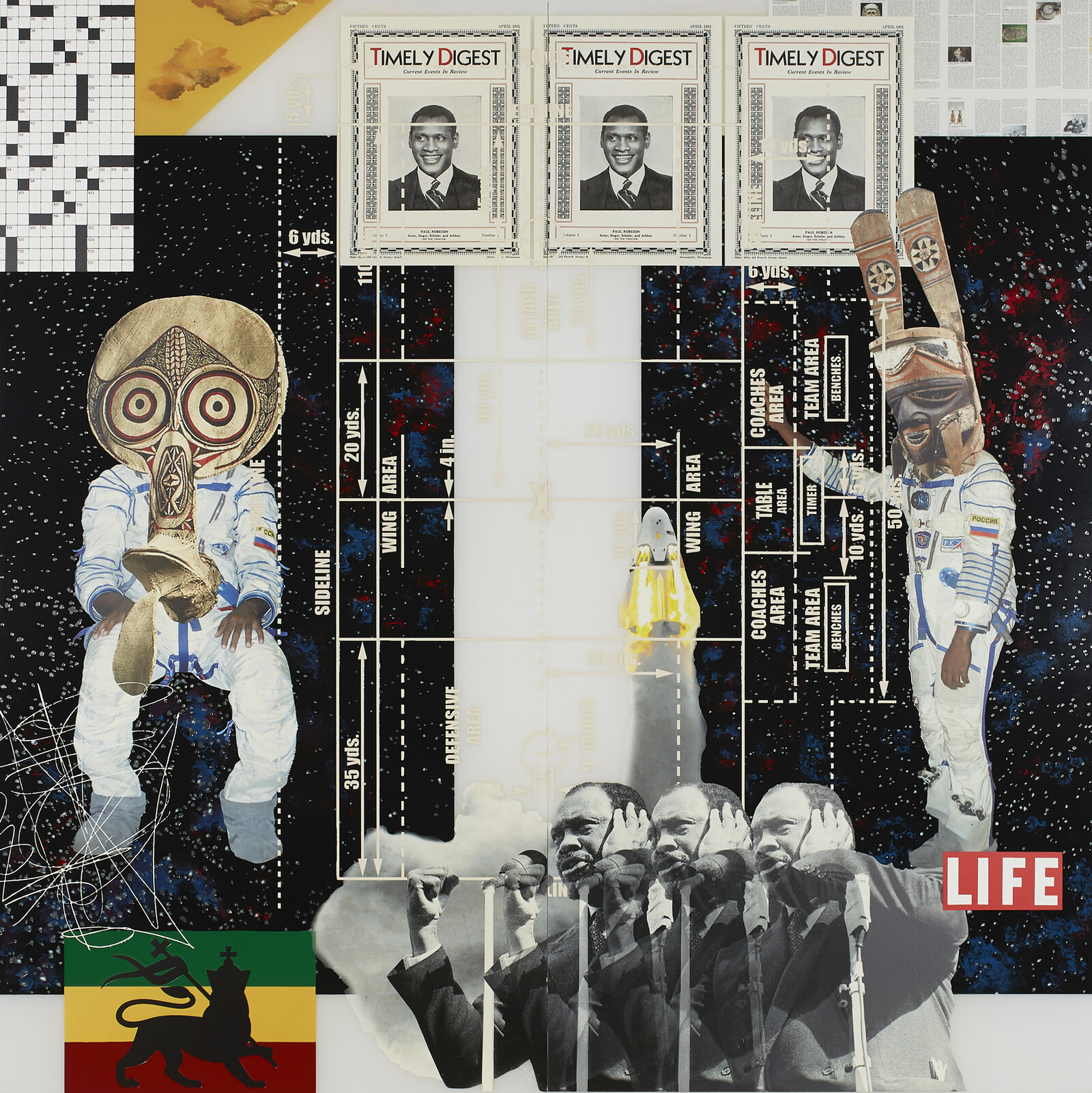

What is the relationship between the performance and the works on view? When I go downstairs the performers are gone, the rooms hidden behind the artworks lining the walls. It’s as if it never happened, and the display feels somewhat conventional. The main gallery includes eight of Strachan’s signature mixed-media on panel works, like huge history paintings that bring together imagery from Life magazine covers, reproductions of artworks, photos from the news, and so on. Every Knee Shall Bow (2020) includes a full-size photo from the coronation of Queen Elizabeth along with two owls, a small image of a television showing an arctic sea, and a photo of Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie on the cover of Jet magazine from 1952 over the headline “Africa’s Last King.”

The references throughout the exhibition run across time, locale, and background. Some of these stories repeat often and in different forms throughout Strachan’s work: he has been working on Henson’s biography, for example, as early as his solo presentation in the Bahamas Pavilion at the 2013 Venice Biennale, but a clear linear history or an exact interpretation is never given. To tell stories, time and again, in new versions, methods, and mediums, is to explore how complex and lingering these supposedly invisible histories are, how is it always possible to trace them. Instead of pressing a singular meaning, the performers fill the space with intention. The exact narratives feel slippery but a feeling lasts—asking, pleading, pointing to an elsewhere (the past, the stars, the song), and a pressing, remaining, always present desire for change.