When the Nigerian government confirmed its plan to construct a new capital in the seventies, it was intended to be a glorious symbol of a prosperous independent nation. Situated in the middle of the country, Abuja would unify the federation’s distinct ethnic groups, redistribute its growing population, and give concrete form to its booming oil revenue. But, mired by decades of political maneuvering and mismanagement, the city instead became a notorious example of the government’s neglect of its people in favor of ruling elites and foreign partners. The contract for the masterplan was won by a consortium of American firms and Japanese architect Kenzō Tange was hired to design the Central Business District. Over 800 villages were dispossessed of their ancestral lands to make way for the city, where insufficient housing stock later forced many into slums on the outskirts.1 The new capital had been dreamed up in corporate boardrooms around the world. In Rahima Gambo’s exhibition at Gasworks, a site-specific installation informed by archival research on Abuja’s development, it is as if things in one such boardroom have gone awry.

Two projectors play helicopter footage of Abuja, after its inauguration in 1991 but seemingly still under construction, on opposite walls. They each present the clips in a grid of nine channels—laid out like CCTV monitors—that loop on and off out of sync and so animate the dark space with their shifting light. The city emerges through dusty air: thousands of buses and cars parked by freshly tarmacked highways, bulky concrete buildings surrounded by cranes, markets, scrapyards and a half-built church. These images beam through panes of glass held in old whiteboard stands that dissect the room and are covered with circular yellow stickers. And four plastic crates sit across the floor, topped with household objects— paperweights, domino tiles, copies of Metro newspaper, and little jars of vegetable oil.

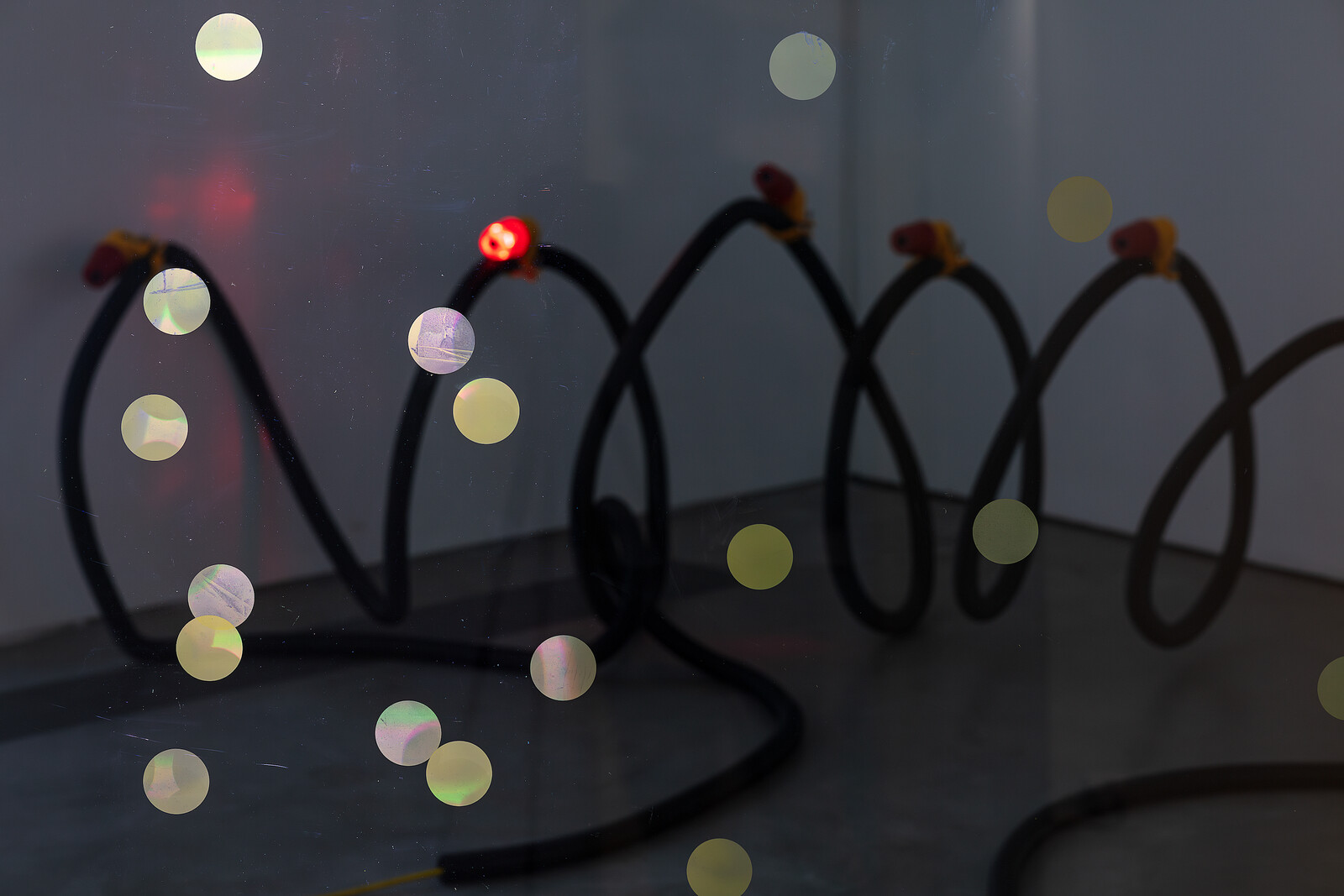

Echoing the helicopter’s winding trajectory, a yellow cable snakes between crates and over stands. It is wrapped in the corner with a segment of black tubing that rises off the ground in a series of loops, each topped with a red light, one flashing. Then the wire disappears into a pile of rubble next door where a map of Abuja drawn in the dirt reveals a buried lightbox. Facing the luminous diagram is a wall of ventilation fans—steel boxes with round holes— whirring away and circulating the smell of damp earth.

Walking round the drawing, looking down at it glistening in the dark soil, is like flying over a city at night. Now I am the circling aircraft, the boxes to one side become apartment blocks and the wire a winding road. Beyond the map itself, the installation seems to employ a cartographic register in which every small item stands for something vast. As a result, the overwhelming feeling is of distance, of things receding as I approach them. Unlike most art based on archival study, the work offers minimal information about its subject. And in contrast with the human focus of much documentary practice—including Gambo’s own photographic projects on the lives of Nigerian students in the wake of the Boko Haram insurgency—it tells us nothing about people in Abuja, who appear only as crowds of pixels swarming below. In this way, she replicates the perspective of no human body but the faceless corporate body that masterminded the construction from afar.

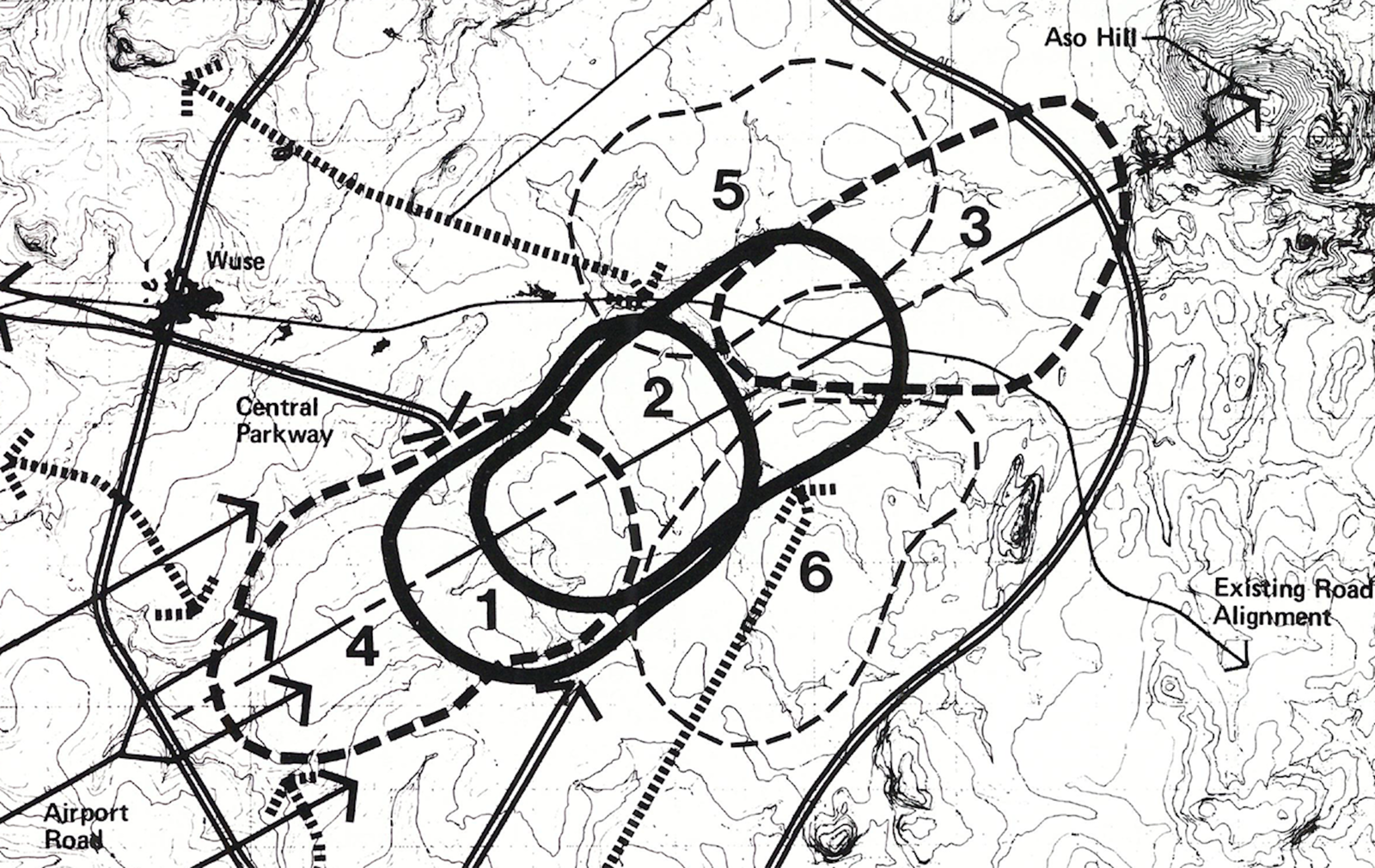

The installation rehearses the search for a perfect spot on which to erect Abuja. Our eyes are sent looping round, in helicopters and along cables, as if homing in on a destination like the rings drawn over potential sites in the map on the exhibition poster. Gambo describes the capital as an “all-seeing eye,” its geographical centrality facilitating the exercise of hegemonic control. But here the search for a centre is rendered futile, there is no singular destination. Circular forms—each like a city on a map—proliferate in the red lights, air vents, jars, paperweights, even the spots on the dominoes. Stickers multiply in shadows bouncing around the walls and spotlights are doubled as they shine through slanted panes of glass. With its kaleidoscopic refractions, the work refuses to let the eye settle and frustrates the urge to achieve scopic control. Gambo retroactively robs the government of the object of its desire, mocking the brute assertion of centralized power.

Nigeria remains oceans away, but the rubble on the floor is from just outside the gallery here in south London, where hundreds of flats are being built on a decommissioned gas storage facility—a familiar sight in a city increasingly dominated by dull blocks of unaffordable housing. Although the construction of Abuja and development in London are both defined by the capital accumulation of powerful stakeholders, they represent totally different contexts. Gambo raises a possible parallel without excavating the local setting in any depth. The bluntness of her invocation of the building site with a mound of dirt, though, is what makes it revelatory. As I kneel on the rubble, my viewpoint shifts from sky to ground. The helicopter crashes, as it were, the smug detachment of historical research is replaced with the sensory immediacy of a walk through London mud, and the pixelated people no longer seem so remote. We are not just looking down at a fragile world designed by unelected strangers, we are living there.

Hamza Mohamed, “Nigeria: Clearing the locals to make Abuja the capital,” Al Jazeera (11 April 2018), https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2018/4/11/nigeria-clearing-the-locals-to-make-abuja-the-capital.