Textiles are at once commodities, expressers of identity, carriers of stories and of memories. Like photographs, they are images inseparable from their materiality. Sukaina Kubba’s first major UK show centers the artist’s obsessive questioning of how far the recognizable elements of Persian rugs—traditionally based on floral or geometric motifs and textured wool—can reasonably be stretched while maintaining their identity. Crafted from a host of industrially derived materials, using an equally wide range of tools, these works trace paths many degrees removed from their design inspirations.

A chance encounter with an Iranian Senneh carpet while on residency in the Atacama Desert in Chile provides one point of departure, prompting Kubba to connect the carpet’s floral pattern to its function in nomadic cultures. “Rugs are gardens in the desert,” Kubba says in the exhibition’s accompanying short film, referencing the way carpets are often the first objects to be set up in a new camp. Kubba spent the entirety of her Atacama residency carefully copying the carpet’s design with pen on tracing paper. The resulting work, Corners of Your Sky, Alula (2022), is as delicate as tissue but speaks of Kubba’s determined persistence to complete the tracing. Hyper-detailed in the lower left corner, the artist’s realization of the time limitations of her residency is made visible through the decrease of information as the tracing spreads out across the paper.

This imperfect copy serves as an anchor for a suite of variations, each new version rendered in a different material or technique. Through these processes of transformation, certain details come into focus while others recede, encouraging different ways of looking at the original—only to remember that all of these “originals” are also copies. There’s a black bioplastic reproduction, drawn by Kubba with a 3D pen (Corners of Your Sky, Al-Qantoor, 2022). Its web of barely held-together thread draws attention to the pattern’s organic qualities, where abstract geometry becomes a school of swimming fish or a child’s scribbled trees. Nearby, a pleasingly messy ink-on-pink latex rendition (Corners of Your Sky, Ankaa, 2022) highlights the intuitive design process typical of Senneh rugs.

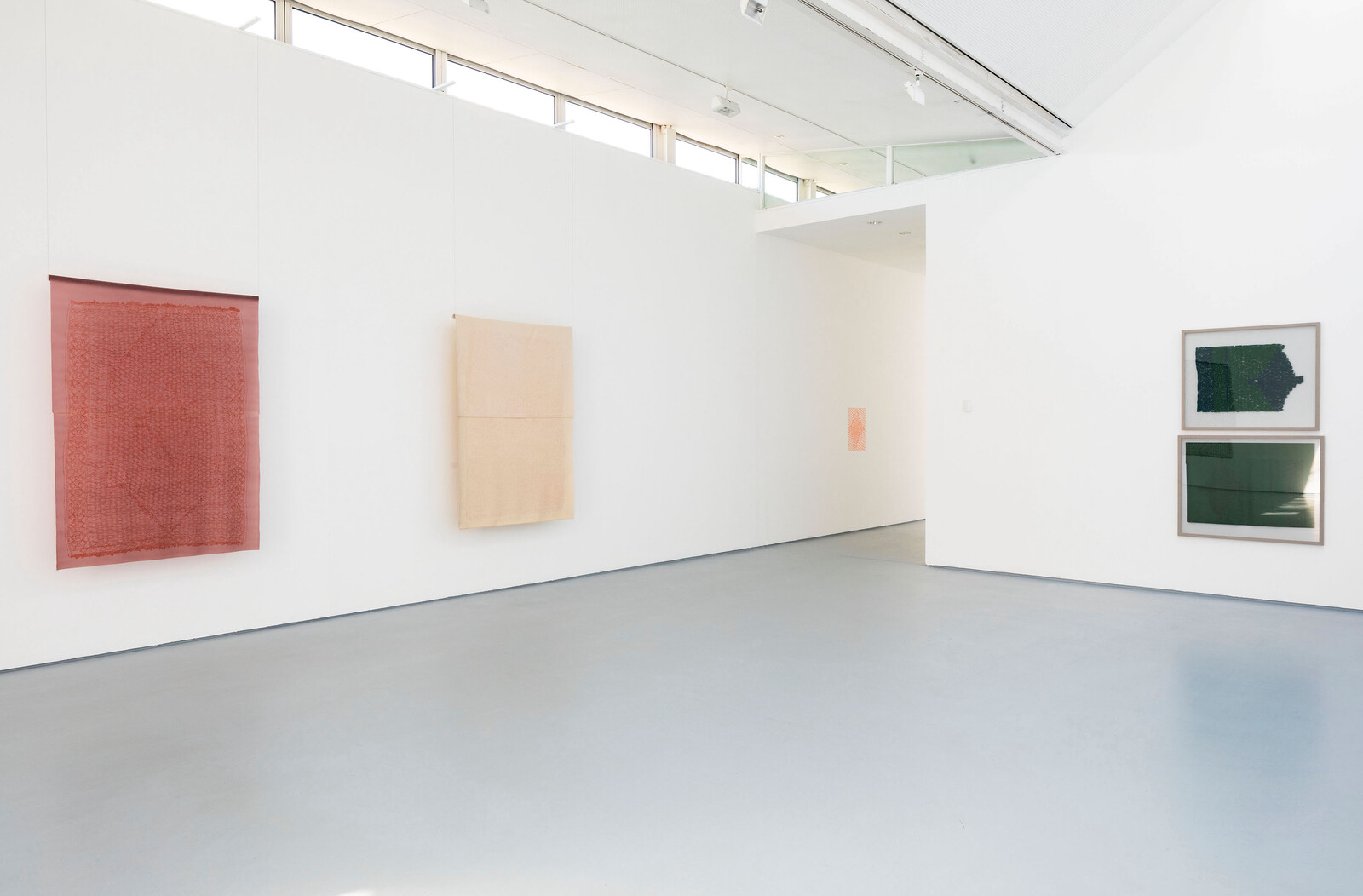

In the large, sky-lit main gallery, Kubba explores two designs from the archive of a significant Scottish carpet manufacturer, Stoddard and Templeton (1871–2006), that often sent staff to copy Persian rugs at the V&A. Kubba traces and scans sections of the copies before subjecting them to a series of transformational processes. As stories in oral cultures change from one recital to the next, so Kubba modifies with each repetition. The pattern referenced in the “Mountain In the Room” series (2024) features a dense profusion of flowering plants, two birds hidden among the vegetation. To provide stabilizing strength for her black, 3D-printed version, Kubba draws a support structure of rhythmic vertical lines into the pattern, pinning down the flowers like botanical specimens.

In each of Kubba’s translations—cut out of velvet-like black plastic, burnt into paper, or screen printed in pink ink on paper or fleshy latex—different materials bring new details to the fore. The pattern’s vegetative lushness sings most loudly on latex, its striking geometry revealed best by the cut-out effect of the 3D-printed plastic. By stripping her palette to black, white, and muted pinks, the graphic, expressive quality of Persian rug patterns dominates in the absence of their traditional vibrant colors. And despite the apparent technological distance between hand weaving and 3D printing or laser etching, all are united by the line: the pass of laser across paper recalls the pass of the shuttle across the warp.

With her acts of repetition, of tracing and copying again and again, Kubba finds new languages to reveal Persian rug patterns afresh, to explore their cross-cultural histories and institutional collecting practices. In doing so, Kubba achieves a means of communication, as Luce Irigaray wrote in “This Sex Which Is Not One”, that is “constantly in the process of weaving itself, at the same time ceaselessly embracing words and yet casting them off to avoid becoming fixed, immobilized.”1

Luce Irigaray, “This Sex Which Is Not One,” in New French Feminisms, ed. Elaine Marks and Isabelle de Courtivron (New York: Shocken Books, 1981), 103.