The photographer Mo Yi describes himself as “a stray dog.” It’s a useful metaphor for understanding both his peripatetic life and his restless approach to street photography. The images collected in his first monograph to appear in English—published to coincide with exhibitions at Beijing’s UCCA and Rencontres d’Arles curated by Holly Roussell, who edits the book and contributes the first of two essays—are the result of his rigorous commitment to chance.

As Christoph Wiesner notes in the second essay, Yi’s photographs of urban life, captured mostly outside and on the move, were inspired in part by Jackson Pollock’s action painting. He took these pictures not just intuitively but almost at random, moving the camera, his body, or both, sometimes mounted on his arm or hung around his neck, and often without looking through the viewfinder first. The mostly black-and-white photographs that result are as blurry, claustrophobic, and raw as you’d expect. They suggest the adrenalized mood of a country disoriented by breakneck change and uneasy about the relationship between the individual and the collective.

The series that opens the book, “1m—The Scenery Behind Me” (1988–89), features a handful of proto-selfies. Yi’s scrunched frown or truncated forehead appears at the bottom of the frame, moving through crowds like the prow of a boat. He shot other photographs from below the waist, the level at which stray dogs navigate the human world. To take them, Yi mounted his wide-angle camera on the end of a stick and activated it with a remote button, an approach that in Philip Tinari’s words “hovers somewhere between conceptual rule and performance score.”

The two sets of dogs’-eye pictures included here (“I am a Street Dog,” 1995, and “Red Streets,” 2003) offer a decapitated vision of urban life in which identity has been subsumed into faceless, collective movement. The lens excludes the features by which an urban population might be individuated to focus instead on knees, shins, skirt hems, sandals, white socks, businessmen’s brogues, the blurred spokes of passing bicycles. There are no horizons and almost no sky. These hectic and hemmed-in pictures do not evoke an ideologically tight-knit society but something closer to Brownian motion: the random fluctuations of particles suspended in a medium.

Yi was not a static observer of this randomness but an active participant in it. In an interview excerpt included in this book, he describes himself as existing “simultaneously” with the people he depicts, buffeted by the same political, historical, and economic forces. Born to Han Chinese parents in Tibet, in 1958, he grew up on the landlocked plateau of Shaanxi province. He was eight when Mao launched his Cultural Revolution. By the time he moved to Tianjin, in 1982, after a stint as a professional footballer, Mao had been dead for six years. Deng Xiaoping’s market-oriented Reform and Opening Up initiatives were already in full swing by that time, liberalizing the Chinese economy and triggering an explosion of urban development.

As Roussell notes in her introductory essay, Yi was among a number of artists “breaking with the strict orthodoxies that had been dominant during the Mao years” in favor of “individualism and experimentalism.” In 1989, the year of the Tiananmen Square massacre, Yi took part in pro-democracy marches in Tianjin. As a result, he was fired from his job as a medical photographer in a children’s hospital, where he worked after retiring from football. That same year, the deeply disaffected artist made “Tossing Bus,” a series of photographs taken on crowded busses around the city. These pictures of exhausted commuters, with downturned faces and closed eyes, clutching grab handles as though for dear life, are intensely bleak. If the dogs’-eye photographs capture a feeling of turbo-charged aimlessness—heat without light—then the sinister implication of these shots from inside a closed vehicle as it labors through urban sprawl is that some destinations are all too heavily determined.

Roussell deserves praise for overseeing this introduction to western audiences of an artist who is deservedly well known in China and for her essay, which offers context—particularly useful for readers, such as myself, who are less familiar with it—on the historical, artistic, and technological contexts out of which Yi emerged. All the same, it’s to the credit of this photographer’s complex work that one preface, two essays, and a timeline left me with the impression that far more could be said about his practice. The photographs do the talking here, and they reproduce well in book format. Yi shot from the hip, sometimes literally. Many of the lopsided and shaky images are, as a result, unremarkable when considered in isolation. Fittingly, perhaps, they work best considered as a whole—a steady accumulation of verbs, gestures, actions—as you flip the pages quickly, as though in a hurry to be somewhere.

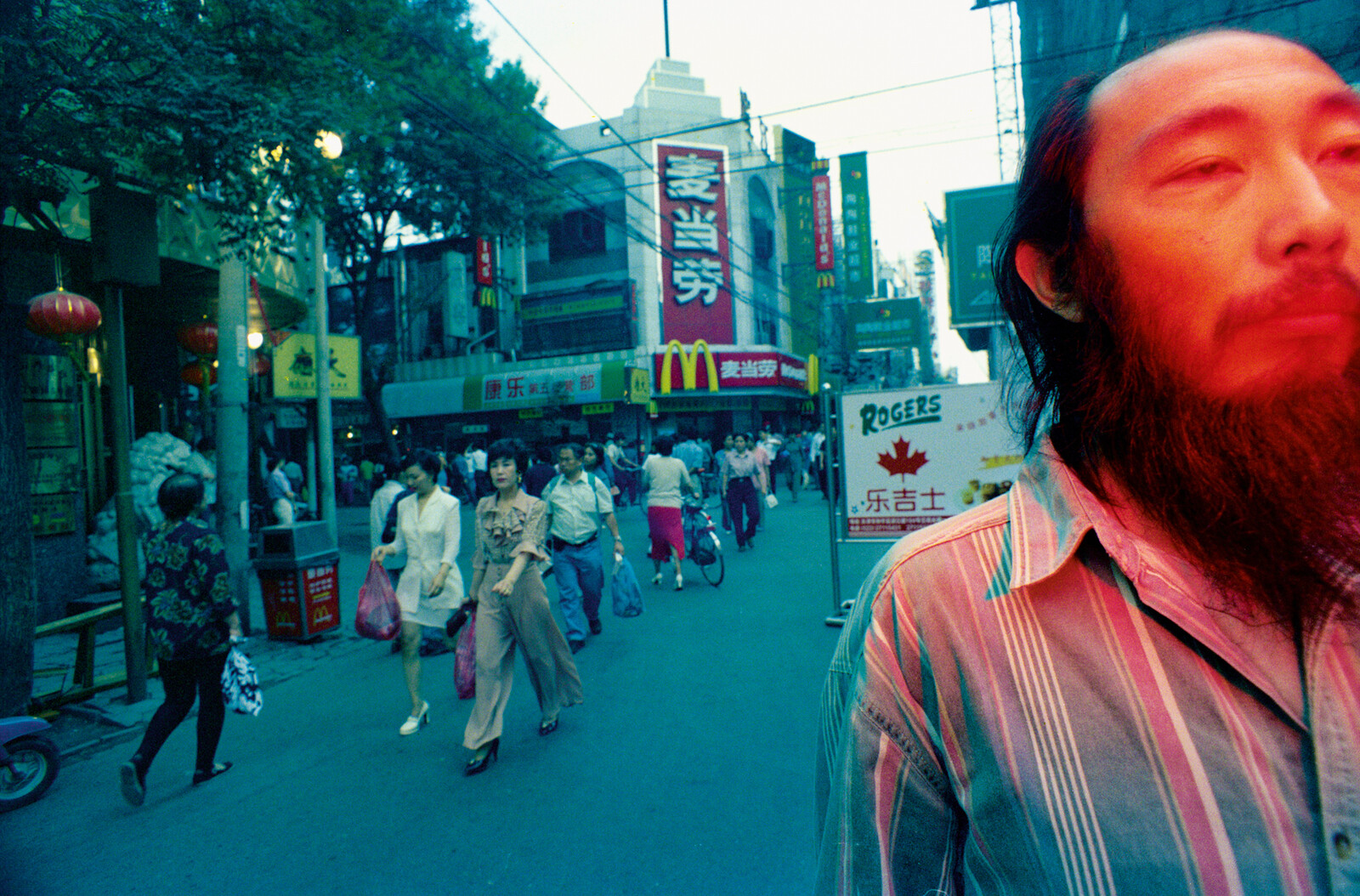

“Scenery with me—a hint of Red” and the aforementioned “Red Streets” (both 2003) mark a significant shift in the feel of the book, as black-and-white gives way to color. To make these photographs, Yi affixed red film to the camera’s flash, so that the parts of the image closest to the lens are bathed in red, while the backgrounds are drenched in blue. The introduction of color electrifies the work. These images feel brasher, more modern, denser with significance. The redness in the foreground could be anything—blood, good luck, the Chinese flag, the illicit tinge of a red light district, rage—while the background blueness points to the other end of the visual spectrum: urban melancholy shot through with a seeming premonition of the high-frequency light of the future, the blue light emitted by laptop and phone screens.

The contrast between Yi and Tianjin, the individual and the collective, is in one sense starker in these series than elsewhere in the book, but the introduction of color implies the potential for harmony, a blending of properties. This sense of possible connection applies not only to Yi and his city but to artist and viewer. In my favorite picture in the book, Yi’s red-bathed face appears at the bottom of a busy intersection. He appears to be crouching. You can’t see his mouth but his eyes are smiling. To gaze into the camera’s lens, as he is doing here, is to peer into the future, to anticipate being seen. In a quote included in the book, he describes the affective impact that his project had on the commuters behind him “touched by the red flash at nightfall in a restless city—and you, the person looking at the pictures.”

Mo Yi’s Selected Photographs, 1988–2003 was published by Thames and Hudson on June 27 in the UK; it is published in the United States on September 17.