In David Medalla’s kinetic, adventuresome world, the smallest of gestures can have far-reaching effects. So goes the origin story of his well-known work, A Stitch in Time, first initiated in 1968. The artist had arranged to meet two of his former lovers, who were passing through London, at Heathrow airport, where he gifted them each a handkerchief, needle, and thread, to help them alleviate the tedium of transit. Years later, in Schiphol airport, he saw a handsome young backpacker shouldering an unusual-looking object: a hefty roll of patchworked fabric, studded with adornments. At the base of the patchwork, in Medalla’s raconteur telling, was one of the original, gifted handkerchiefs. Off went the backpacker and, with him, the fabric creation. After that, Medalla said, “I started to make different versions of A Stitch in Time in different places.”1

A Stitch in Time—a participatory artwork, typically displayed as a long sheet of cotton onto which audiences are invited to sew whatever they choose, using thread provided—is at the Hammer Museum in archival form only: Medalla’s handwritten account of the work’s origin and list of its installations from 1968 onward, together with two small boxes of thread used in previous displays. It’s an intriguing choice. This exhibition rightly positions Medalla as a figure who embraced ephemerality and impermanence as a core principle of his art and, as a result, often left only fragments in his wake. Withholding a more interactive (and Instagrammable) work encourages attention to Medalla’s own yarn about the origins of the piece; among them, the fondly recalled ex-lovers and the conspicuous, handsome backpacker.

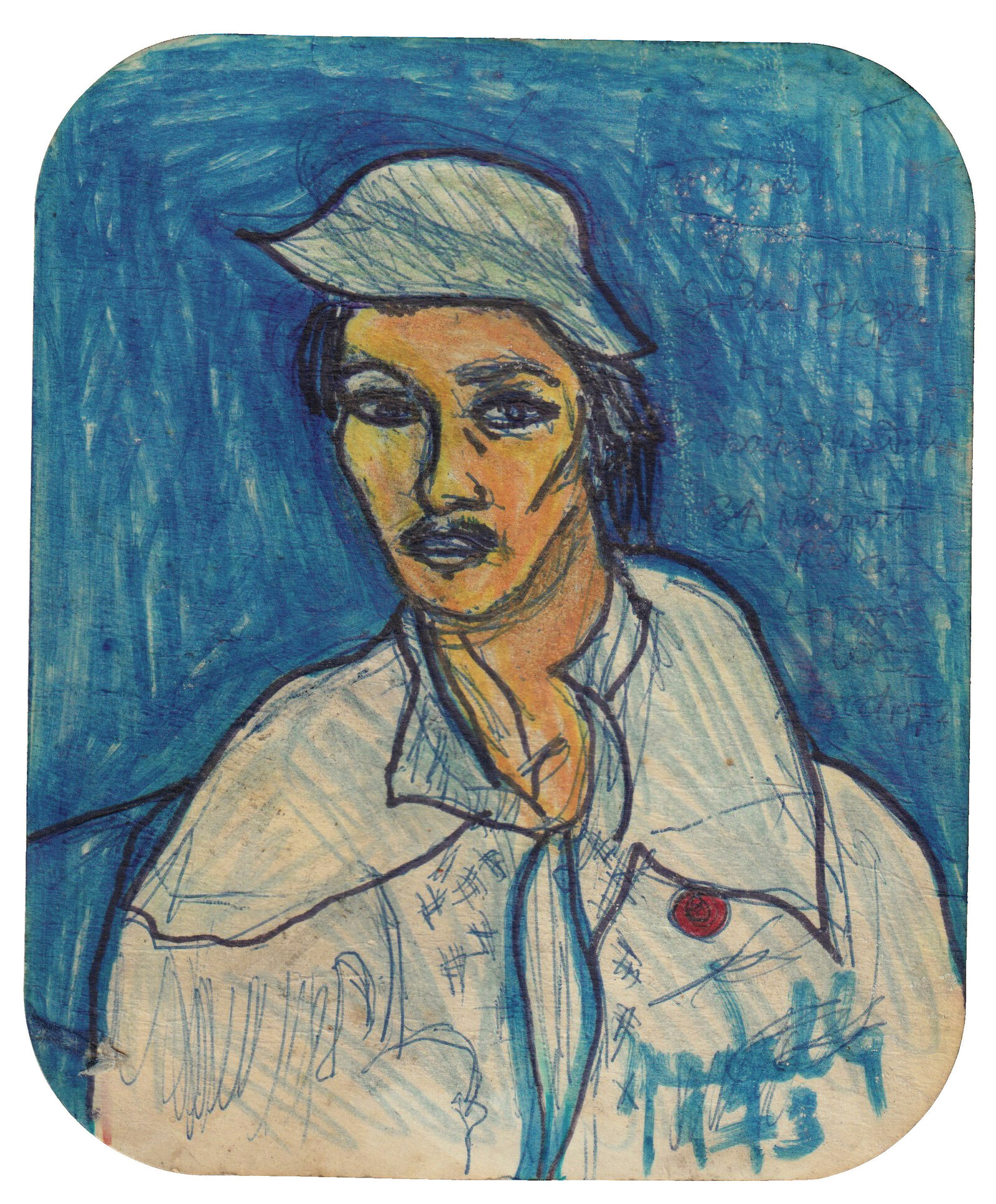

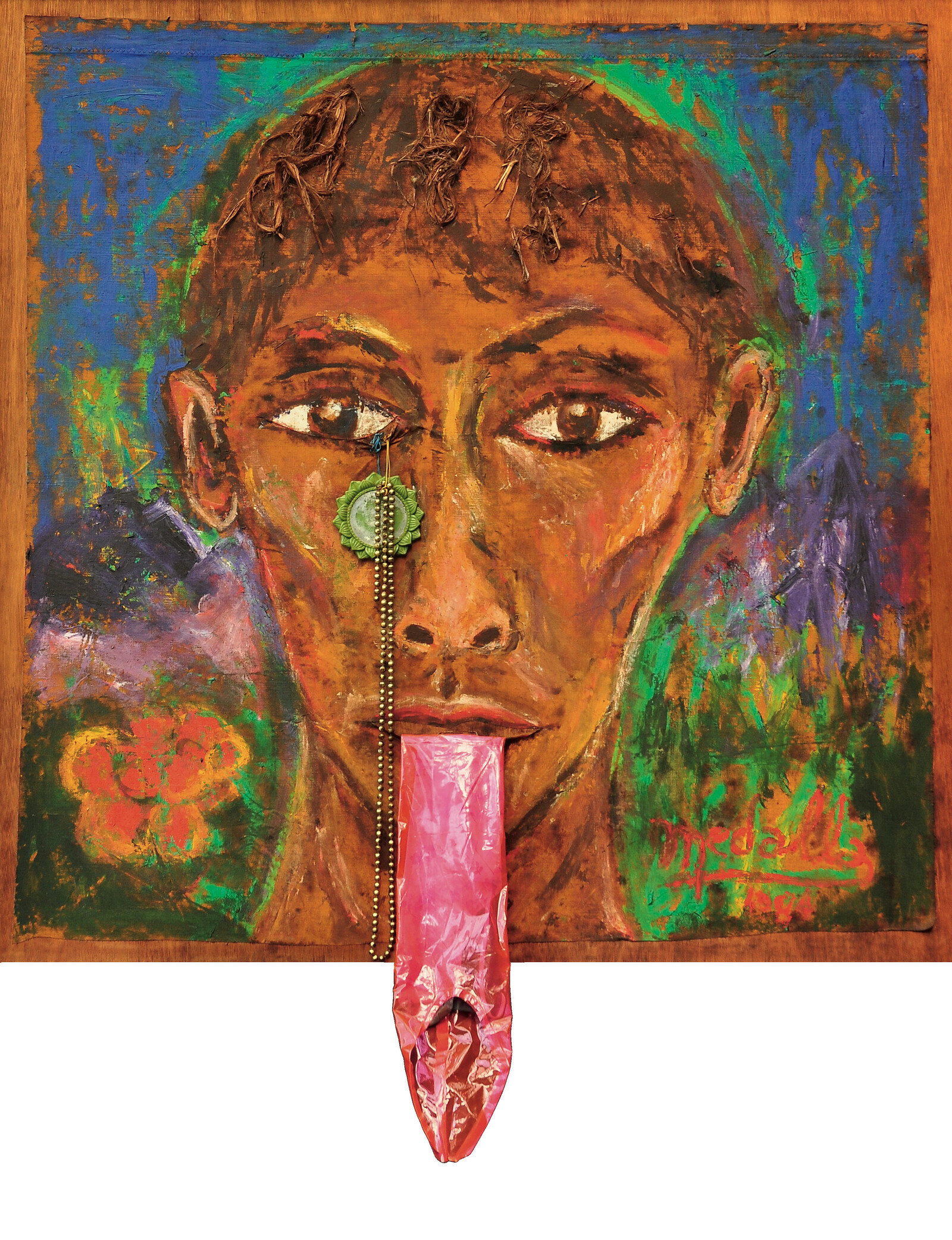

The shift of focus is fitting. Curated by Hammer’s interim chief curator Aram Moshayedi, Medalla’s first comprehensive survey in the United States also focuses on the queer, erotic sensibility that permeates his work; an aspect of Medalla’s art which, the exhibition’s interpretative materials note, most evaluations have “repressed.” Entering the exhibition, viewers are greeted by one of Medalla’s exuberant, early self-portraits of 1956–57, which he signed “Gaybriel,” along with ink drawings: muscular men in courtly poses; boys in symmetrical embrace. Opposite hangs a vibrating pastel dedicated to Arthur Rimbaud, whose provincial hometown of Charleville Medalla journeyed to, in 1960, en route from Manila to London.

While opening up this seam of Medalla’s art for consideration, the Hammer’s exhibition also persuasively shows that the true métier of this most gregarious artist (who once estimated that he met around twelve new people a day) was the interpersonal.2 The exhibition covers in brief Medalla’s distinctive contributions to kinetic art of the 1960s, co-founding London’s Signals gallery, and making machines that eschew clanging industrial noises and destructive effects but instead stroke sand into concentric rings; ooze foam columns that endlessly change form. Medalla’s collaborative ventures, conversely, are given ample room: communal theatrical group the Exploding Galaxy (formed 1967 and disbanded the following year), and Medalla’s synced efforts with John Dugger in the Artists’ Liberation Front (1971–74), and its successor, Artists for Democracy (1974–77), both of which had a mission to make art that amplified global independence struggles.

The material remnants of these ventures are poor documents. Medalla’s “Africa Liberation” drawings (1974), for example, are unfussy, hand-drawn interpretations of photographs originally circulated by solidarity groups in London, pasted onto red cardstock that bears signs of heavy use. But the relative flimsiness of these works points to defining characteristics of Medalla’s art. Ever itinerant, he was also, by necessity, provisional in method. As he grew as an artist, Medalla directed his efforts not toward making refined objects, but an infectious—and archive-eluding—transfer of energies between people. In notes for the Exploding Galaxy’s 1967 dance-drama The Bird Ballet, on view here, he called these energies “audiencedensities,” and elsewhere, “propulsions.”3

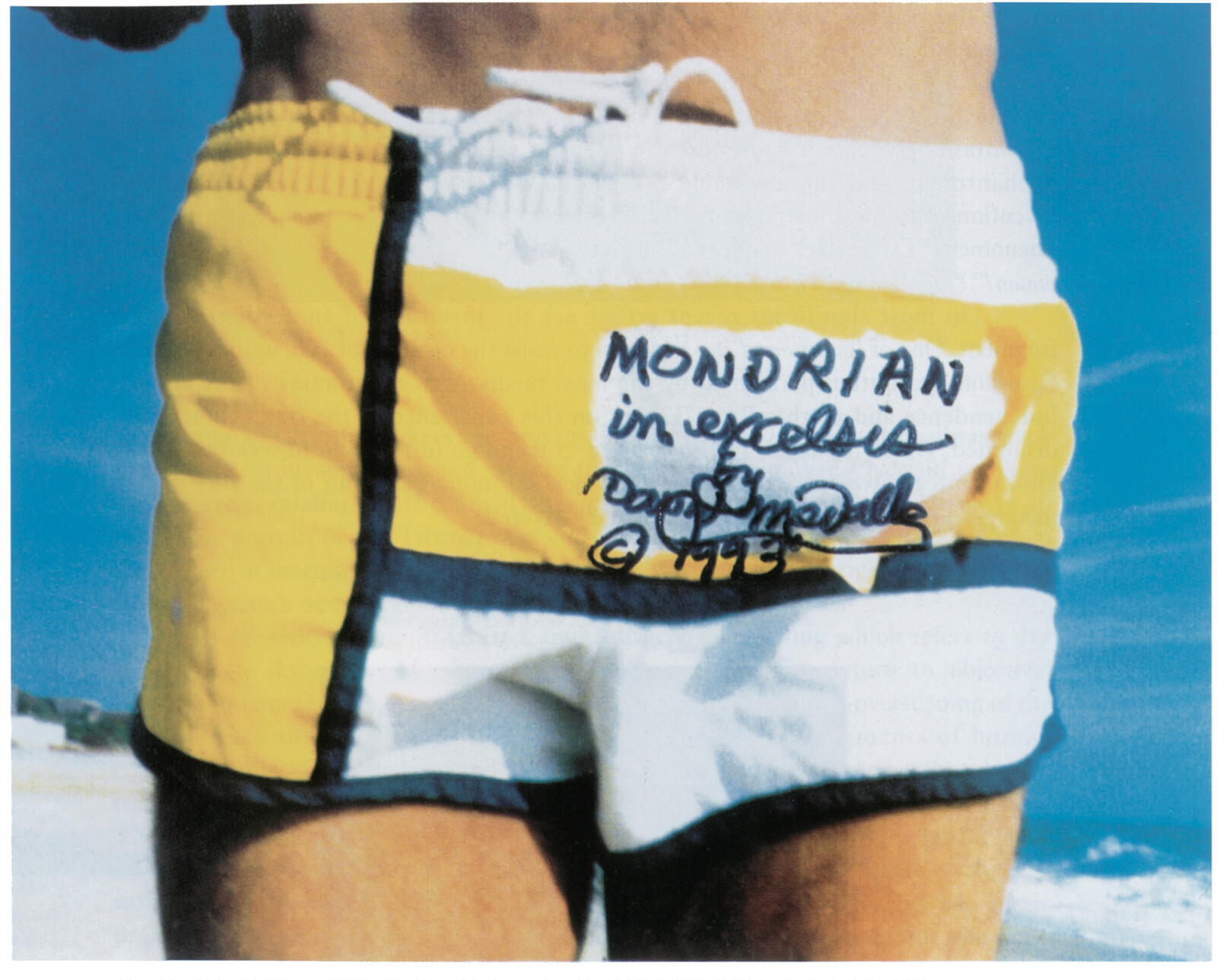

Homing in on the social locus of Medalla’s art, the exhibition’s concluding galleries trace the arc of his work during his generative relationship with Adam Nankervis, whom he met in 1990. A series of photographs captures moments from the duo’s project, “Mondrian Fan Club” (1991–2018): a homage to the Dutch arch-modernist through gestures that are deliberately playful, lowbrow (writing the letter “M” in the sky above Long Island City; Nankervis with an erection while wearing swim shorts emblazoned with a Mondrian grid). An exercise in bridging the gap between art in its raw state and its institutionalization, the snapshots, here framed and gridded, appear knowingly lifeless; removed from their instantaneous vitality.

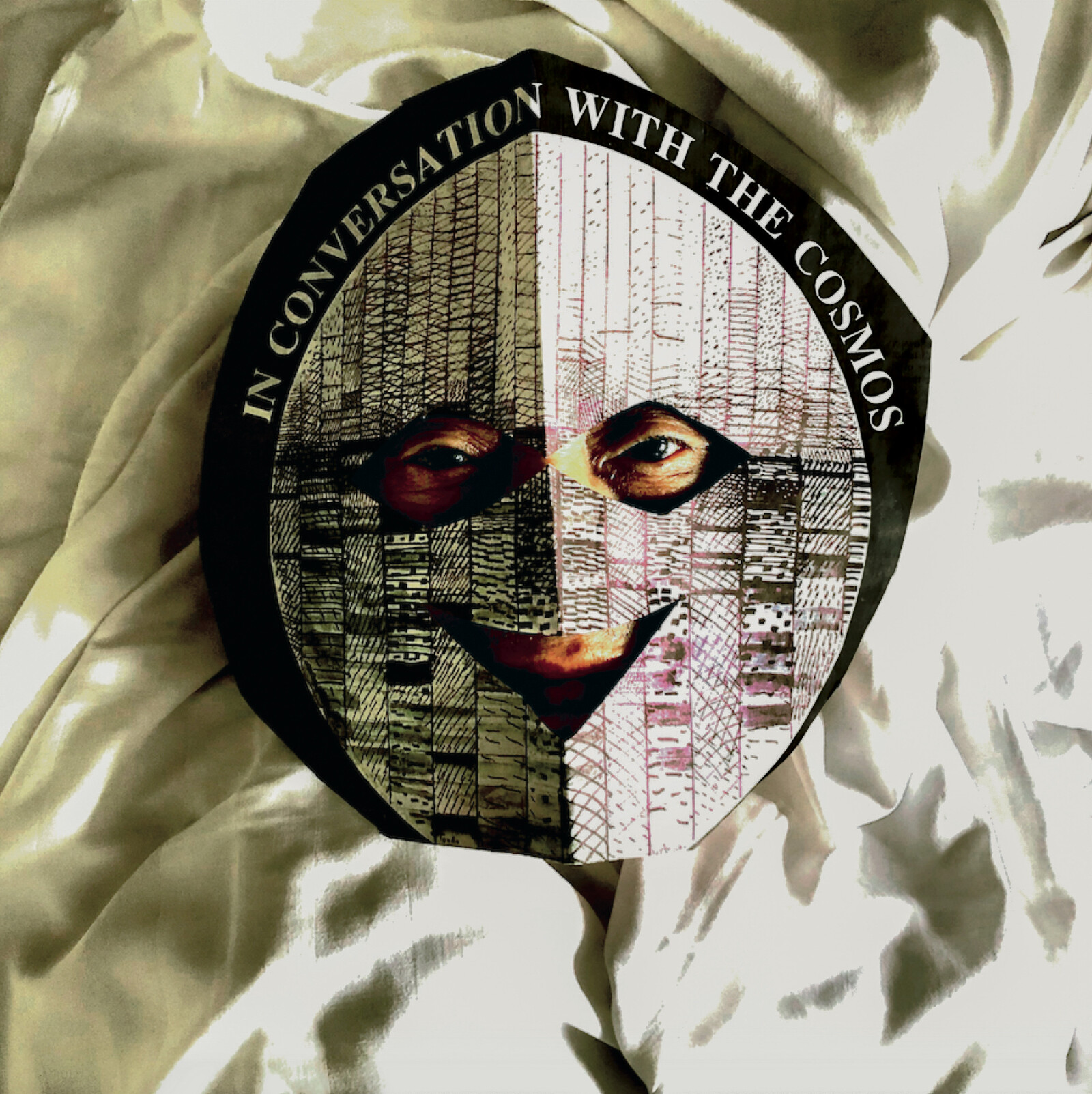

Daring to meld the worlds of high art and private intimacy, “Mondrian Fan Club” has a touching counterpart in “Sirens”: a “ritual of daily masks” and related portrait photographs, credited to the artist and Nankervis, made in the wake of Medalla’s stroke in 2016, which resulted in his partial paralysis and loss of sensation.4 Placing decorative odds and ends—flowers, ribbons, soap bubbles—upon Medalla’s prone face (where he still had sensation) for the simple transformation and physical touch they bestowed, the series underscores Medalla’s provisional way of working, and melds art with the most intimate human connection.

In the column he wrote for local newspaper The Filipino Express while living in New York, in the early nineties, Medalla once described a prospective collaboration with Carolee Schneemann to celebrate the coming millennium: “We will be burying time-capsules of artistic propulsions […] in sacred sites around the world.”5 If the collaboration occurred, its trace has eluded books and museums. May this exhibition spur others to continue to bring Medalla’s extraordinary propulsions back into reach.

All accounts in this paragraph from Gavin Jantjes’s conversation with David Medalla, conducted in 1997 and published in A Fruitful Incoherence: Dialogues with Artists on Internationalism (London: Institute of international Visual Arts, 1998), 94–109.

Guy Brett, Exploding Galaxies: The Art of David Medalla (London: Kala Press, 1995), 18.

David Medalla, “For a People’s Democratic and Socialist Culture,” unpublished statement, February 29, 1972.

Adam Nankervis, “sirens / david medalla + adam nankervis,” https://www.anothervacantspace.com/filter/david-medalla/sirens-david-medalla-adam-nankervis.

David Medalla, “Villa Rides,” Filipino Express, December 31–January 6, 1990.