February 6–June 15, 2025

Nicholas Thomas has characterized Paul Gauguin’s Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? (1897) as a “success as a painting, but a failure as a work of art.”1 Which is to say that while it dazzles through its arrangement of color and form, it travesties the Tahitian culture that it purports to depict and offers no meaningful response to the grand questions of its title. The phrase recurred to me throughout this sixteenth edition of the Sharjah Biennial—curated by Natasha Ginwala, Amal Khalaf, Zeynep Öz, Alia Swastika, and Megan Tamati-Quennell—with its emphasis on work that is, by contrast, firmly grounded in its cultural contexts and unambiguous in its ethical commitments. But it is less clear that all of them fulfil the first part of Thomas’s equation, and triumph on their own terms as sculptures, videos, installations, or any of the other aesthetic strategies through which it is possible “to carry”—as the exhibition’s title puts it—ideas, principles, and feelings across the borders separating people, communities, and cultures.

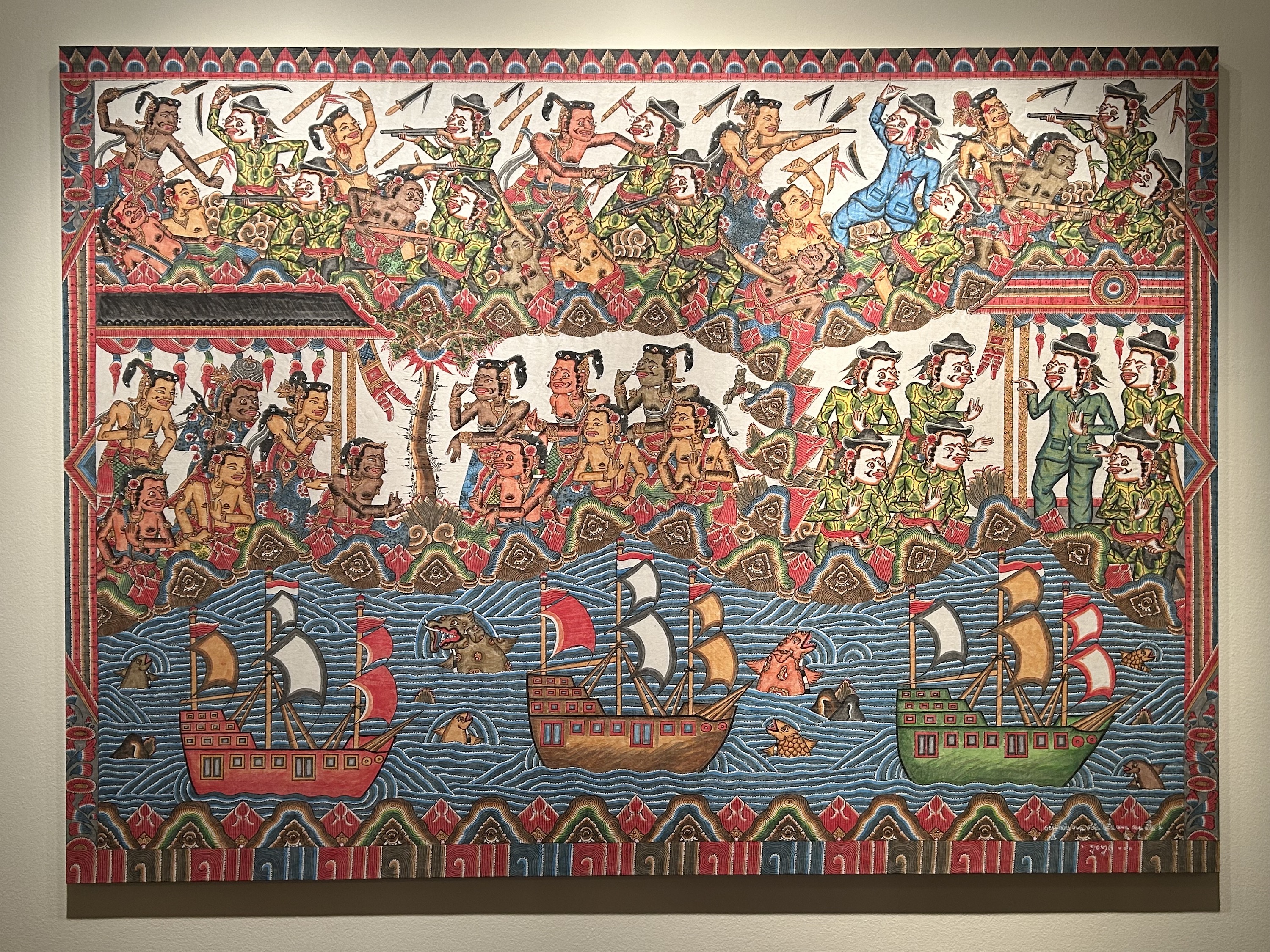

Mangku Muriati’s paintings succeed on both counts. Drawing on the traditions of Balinese puppet theater, the new commissions exhibited on Calligraphy Square, in Sharjah’s reconstructed historic center, are both visually arresting and rewarding of long contemplation. Yet the compositional schemes that make it so are not unique to the Kamasan style in which Muriati was schooled: The Tale of Dyah Tantri (2024) is divided into an unstable grid by intricately patterned bands of brilliant color like garlands of flowers, establishing panels across which dance a cast of humans, animals, and monsters. The serial storybook form—which presents the stories told by a young woman to a murderous king to avoid the fate of his previous wives—calls to mind the visual narratives of both Renaissance polyptychs and the comic book, while the startling resemblance of Dyah Tantri to Scheherazade signifies either some literary cross-pollination or that the foundations of myth are deeper than the diverse traditions that spring from it.

These exceptional paintings far exceed the bald illustration of a culturally specific history, for all that their depictions of Dyah Tantri or the resistance of a Balinese queen against colonial Dutch troops (in Kusamba’s War, 2024) carry resonances in the present. But it is not always the case that a work’s messages are animated and enriched by the manner of their execution. When the wall text accompanying Richard Bell’s work at the Sharjah Art Museum quotes him as identifying as “an activist masquerading as an artist,” you wonder why he should not be taken at his word. This is not to say that his attempts to draw connections between the Indigenous Australian Rights Movement and civil rights associations in the USA and Palestine should be excluded from the museum, but rather to question why they need to be dressed up as art so bland and formally conservative as these paintings of protest scenes in order to gain access to it. Bell’s own Embassy (2013–ongoing), which was installed at Documenta 15, offers its own compelling example of how political actions can be incorporated into a biennial without affecting to belong to the same category as Muriati’s paintings, against which they must inevitably pale.

At the same venue, Photo Kegham of Gaza: Unboxing (2020–24) offers a further demonstration that politically charged images are more effective when they are not smuggled in under a disguise. This archive of photographs by Kegham Djeghalian Sr, founder of the first professional studio in Gaza, forms the basis of a partial visual reconstruction by his son of the Palestinian territory’s history since 1944. That the affective power of these photographs derives more from our knowledge of what will come to pass than from their conventional framing does not diminish them, precisely because Djeghalian Jr resists the urge either to overload them with contextualizing information or to make extravagant claims for their technical accomplishment. Nonetheless, they speak: a young boy lies on a sand dune, smiling for the camera, the barbed wire fence separating him from the sea so much a part of the landscape that it does not seem to have occurred to the photographer that it makes an unsettling backdrop for a portrait of carefree youth.

The tragedy of these images is that it should be necessary to present them in a museum. In a less terrible world these family portraits and holiday snaps would be of interest only to the small and geographically proximate community of people they depict; instead, they are an indictment of the failure of the global order and the basis of Djeghalian Jr’s attempts to trace members of a scattered diaspora. These pictures were freighted with a further, almost unbearable weight by the US government’s announcement, on the day prior to the show’s opening, that it intended to transform Gaza into the “Riviera of the Middle East.” And so, in the historical present, it might be argued that one function of this biennial—indeed, a crucial role of art institutions more broadly—is to give shelter to those cultures that are threatened with erasure. The unresolved question is whether this renders moot the artistic value of those works chosen to represent them.

This argument might be understood as a corrective to the old insistence that art’s social content is subordinate to its aesthetics as judged against western standards (which has been used, notoriously, to justify both Gauguin’s racist portrayal of Polynesia, in particular, and to denigrate non-western art in general). It is most convincing when, as in the case of the Photo Kegham archive, that social content is not dressed up to meet precisely those standards; it is less so when, as in that increasingly queasy genre in which local craftspeople are enlisted by a visiting artist to collaborate on the production of a textile work on a predetermined topic, it only succeeds in producing something that corresponds conveniently to expectations of what a biennial artwork in the mid-twenties should look like and signify.

It need not be an either/or, as the many strong works in this show assert. Among them is Alia Farid’s short film Chibayish (2023), which portrays residents in Iraq’s southern wetlands—and the water buffalo with whom they share the ecosystem—through snatches of song interleaved with conversation about life and lingering shots of a landscape compromised by the encroachment of industry. Mercifully untranslated and unexplained, the song and dance of a young man carries the texture of his life across the distance separating it from the viewer. The camera moves from the dust that jumps from the patterned rug beneath his feet to the light that flickers through a wicker lattice, relaying evocative details rather than affecting to capture the whole. This, to adapt Thomas’s formulation, succeeds as a representation of a culture because it succeeds as a piece of filmmaking.

That success is predicated on the acceptance that something is always lost in the transmission, that “to carry” is also to transform. Stephanie Comilang’s Search for Life II (2025), is elevated above an academic study of the precarious livelihoods, globalized markets, and diaspora identities connected by the industrialized pearl industry through its focus on the stories and songs of an Emirati-Filipina K-pop band member and a Bajau pearl fisher. The two-channel video installation is sympathetically installed beside Monira Al Qadiri’s Gastromancer (2023) on Al Mureijah Square, one of the few occasions on which it is possible to discern a guiding logic behind the arrangement of works in the show.

Indeed, the incoherence of a biennial encompassing three hundred works in 13 venues across the emirate (including a village buried beneath sand dunes, an abandoned clinic, and an architectural landmark known as the “flying saucer”) is initially frustrating. Whenever a line of curatorial inquiry emerges, it is soon abandoned or even contradicted: Rully Shabara’s mock-ethnographic display of artifacts recovered from a fictional—and, naturally, nonhierarchical and perfectly noble—civilization (Khawagaka, 2012–ongoing), for instance, might seem to signal a skepticism about the dangers of idealizing, which is to say othering, the material cultures of the past. Yet it sits uncomfortably among so much work that seems unreflectingly to valorize ancient craft traditions and forms of ancestral knowledge for their own sake.

After a time it becomes possible to dimly discern some embryonic exhibitions within the exhibition. There are a number of thoroughly researched and intelligently staged monographic presentations of historical artists (most rewardingly, of the nomadic painter SM Sultan, the multidisciplinary artist VISWANADHAN, and the dancer and choreographer Chandralekha); an intriguing experiment in the relationship of an exhibition to its written publications in the form of a collaboration with the publishing house YAZ; a raft of works exploring the interplay of loss, mourning, and memory (notably in the sculptural installations of Fatma Belkıs and a new commission from Cécile B. Evans); and reflections on the means by which traditional forms might be carried into, in order to act upon, the present. Chief among the latter is Dilek Winchester’s captivating Choreographies on the Unread (2024), which translates the rhythms of traditional Turkish poetry into the patterns of tap, offering a way into works of literature that would otherwise have remained entirely obscure to me.

If it is a stretch to say that the incoherence of this exhibition is by design, then it is also a practical consequence of commissioning five curators with different commitments and—more generously—a reflection of the world in which it takes place. The biennial’s longstanding and admirable advocacy of art from the Global South here takes the form of a staged difference of opinion about its relationship to the codes and conventions of the globalized field of contemporary art, the political functions it should serve in the present, and its ethical responsibilities to rapidly disappearing pasts and futures. All of which is difficult to navigate but feels oddly appropriate to our messy, uncertain, and deeply conflicted historical moment. This is a “strange realism,” as Ursula K. Le Guin put it, “but it is a strange reality.”2

Nicholas Thomas, Gauguin and Polynesia as quoted in Julian Bell, “Grizzled Eagle,” London Review of Books (26 December, 2024).

Ursula K. Le Guin, “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction,” in Dancing at the Edge of the World (New York: Grove Atlantic Press, 1989).