Alongside pioneering abstract art in Indonesia, Ahmad Sadali was an influential scholar and religious thinker, a public muralist who strived to ignite the spirit of liberation during the 1945 war, a national representative at UNESCO, an observer at the Bandung Conference of 1955, and an orator at Jummah prayers who gave a celebrated speech at Istiqlal Mosque, Jakarta, in 1975. Yet even before his death in 1987, his legacy—like that of the Bandung School with which he was affiliated—was dogged by controversy over its relationship to western art histories.

“Bound to the Earth, Aspiring to the Sky,” held in a gallery owned by one of his former students, is timed to celebrate the centenary of Sadali’s birth and grouped according to the artist’s formal tendencies—from simple geometries to golden ornaments—instead of a rigid chronology. In the larger of the gallery’s two rooms are forty-five canvases that evidence the artist’s distinctive styles, from the still lifes and Cubist styling of his early career, to later works incorporating Quran verses and the Names of God into calligraphic abstractions. The show draws attention to a controversy begun in 1954, when art critic Trisno Sumardjo argued that a group show of Bandung-trained artists “served the western laboratory.”1 While still providing the post-independence historical context in which his works were made and understood, this show instead foregrounds the way that Sadali’s art embedded spiritual principles (“the sky”) in social life (“the earth”).

Made when he was still a student, Sadali’s Chair and Boat (1949) and Kembang Matahari [Sunflower] (1952)—for which he won the national art prize that fueled a meteoric rise—are characteristic of the wider movement of the Bandung School, with traces of the European masters lingering. In the former work, the cubist configuration of its titular objects is reminiscent of Georges Braque (as is the brownish green palette and the interplay of shadow and light). In the latter, a bright yellow floral composition recalls Matisse’s sunflowers. Critics contrasted such modernist abstraction unfavorably to the socialist realism of the contemporaneous Yogyakarta School which, they argued, more closely represented the life of the people.2

Fittingly, however, the calligraphic abstractions make the loudest, most explicit defense of Sadali’s transcendental art. This section of the show marks the period when Sadali (and other Bandung artists such as Abdul Djalil Pirous, Abay Subarna, and But Muchtar) steered modernism towards the popular genre of Islamic calligraphic abstraction in the 1970s and ’80s. This was not without controversy: at that time, many non-painter/trade calligraphers feared that the sanctity of Arabic script could be “tainted.”

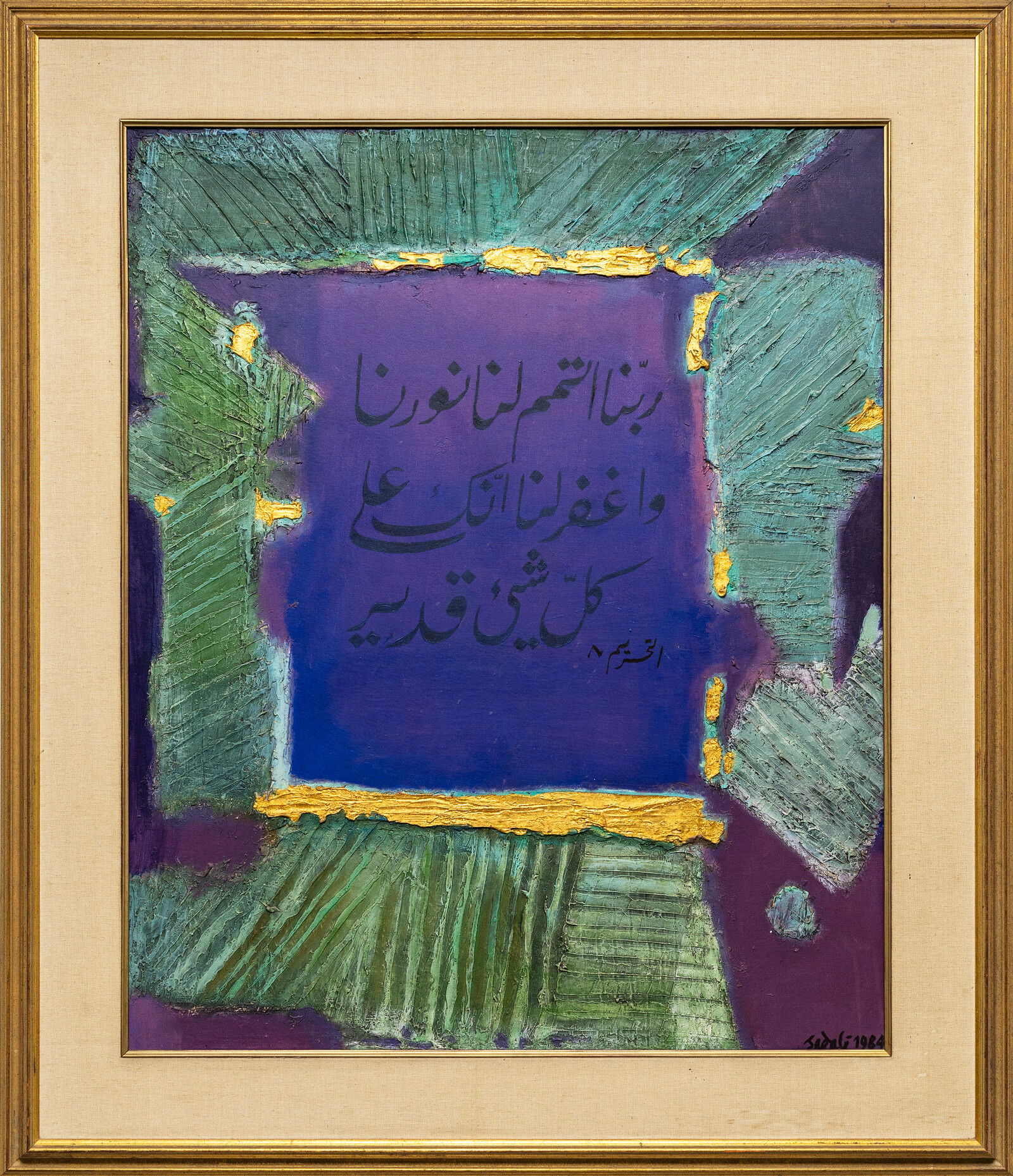

While his peers tended to assimilate the typographic style of local script and murals, Sadali’s calligraphic works stayed true to classic Persian khatt while setting it in a modernist context. In one untitled 1984 work shown in the exhibition, he painted a brief quote—the prayer at the end of the complete verses—from Surah At-Tahrim 66:8 in flowing cursives and lean, hanging strokes emblematic of the Nastaliq hand. At the same time, he experimented with materials such as relief-like textures of marble paste and gold leaf found in many works, including another untitled painting shown here.

Dating from 1983, the work features Surah Al-Ghashiyah 88:17–20, which contrasts the gilded, thick brown impasto with the thin impression of dark purple-light blue oil on canvas. “Then do they not look at the camels,” the painting reads in Arabic, “how they are created? / And at the sky – how it is raised? / And at the mountains – how they are erected? / And at the earth – how it is spread out?”3 The sense of meditative wonder informing this work suggests it might be thought of as a form of dhikr or remembrance of God, a practice that he also preached.

As the debate around Bandung dissipated in the mid-sixties, Sadali shifted gears. The dominance of LEKRA (the Institute of the People’s Culture, a sociocultural movement associated with the Indonesian Communist Party) proved that the faction promoting “art for the people’s sake” had the upper hand while, from 1965 onwards, the New Order depoliticized the arts and persecuted alleged communists. This transitional time, during which Sadali was settling into his university tenure and more frequently presenting at cultural diplomacy events and religious conferences, is less well-known than his involvement with the Bandung School, and its inclusion in the exhibition sheds light on the rest of Sadali’s oeuvre.

In the gallery’s smaller room, a cluster of twenty-two monochromatic pencil and charcoal drawings from the 1970s, all untitled except Garis-garis yang Ditinggalkan [Lines Left Behind] (1973), show his affinity for circular shapes and linear patterns. These repetitive compositions and smudgy gradations punctuate the periods between Sadali’s aforementioned periods, when he moved on from his color-clashing Cubism and other abstract flourishes toward more spiritual allusions: metaphors of nature rendered tactile in earthy tones.

This exhibition offers a refreshing take on Sadali’s legacy, taking it beyond the controversies of his time. By inviting visitors to encounter his nearly four decade-long trajectory through a stimulating display of biographical memorabilia—including video-style slides of the photographs he took of the Bandung Conference, governmental medals, and especially the audio recordings of his speech on art, pedagogy, nature, and religion—a room of archival materials further illuminates his sociopolitical commitment and ultimate principle of faith, which seeped into all his works. Not only did he paint and preach the holy verses, he also drew aesthetic prompts from them. Above all, Sadali sought to express his humility and wonder before the majesty of God and His creation—perhaps the true “laboratory” he served.

Trisno Sumardjo, “Bandung Mengabdi Laboratorium Barat,” Siasat, December 5, 1954, republished in Seni Rupa Indonesia dalam Kritik dan Esai, eds. Bambang Bujono and Wicaksono Adi (Jakarta: Dewan Kesenian Jakarta, 2012), 131–133; https://archive.ivaa-online.org/khazanahs/detail/3662.

The Japanese occupation used a similar accusation (“too western”) against PERSAGI, or the Union of Indonesian Painters—that played a significant part in the advancement of modernism in 1930s Indonesia with their strong critique of Mooi Indie-style paintings of exoticized women and sterilized landscape popularized by the Dutch colonial patronage, mainly to promote idyllic tourism—to disband them in 1942 as a pretext for founding a reactionary body Keimin Bunka Shidoso, where Indonesian artists must assist with pro-Japan propaganda during the Pacific War.

Saheeh International translation of Surah Al-Ghashiyah 88:17–20, the verses from Sadali’s 1983 painting.