February 23–July 14, 2024

Flowers were important to Jonas Mekas throughout his life and work, serving as a recurrent visual and thematic motif. Starting from the early 1950s, after his arrival in New York, the great avant-garde filmmaker would record his daily life, later revisiting and editing it into cohesive yet nonlinear stories. Among the best-known of these films is Lost, Lost, Lost (1976), which contains a memorable scene in which the artist, referring to himself as a “monk of the order of cinema,” captures close-ups of a grassy field in the early dawn. This almost ritualistic act illustrates perfectly how Mekas connected to nature through the medium of film.

Not only did he credit his early mentor, Marie Menken, with teaching him how to film these delicate subjects (Menken’s 1957 Glimpse of the Garden uses rapid edits to capture their ephemeral beauty), but they are frequently referenced in his poetry: “Flowers die / and return to the earth, / with the same scent / touching faces,” he wrote in 1966.1 Given his lifelong fascination with the natural world, it seems appropriate that his final film Requiem (2019)— made when he was ninety-six, now installed in this deconsecrated seventeenth-century church—should be an observation and celebration of flowers.

Requiem premiered at The Shed in New York in 2019, a few months after Mekas’s passing, and has since been installed, occasionally accompanied by live music performances, at venues around the world. But it finds particular resonance in the San Carlo Cremona, which in 2021 was repurposed as a space for contemporary art projects by Lorenzo Spinelli. Presented in collaboration with Apalazzo Gallery and the artist’s estate, this installation of Requiem is made particularly compelling by a setting that complements the film’s themes.

Viewers are greeted by a vitrine of archival materials, including writings reflecting Mekas’s interest in flowers and documentation of his emigration from Lithuania and life in New York. There is an emphasis on his early years in the village of Semeniškiai, the idyllic setting of which would infuse his later work. In the interior of the San Carlo Cremona, which is pierced in places by sunbeams that illuminate the Baroque architecture, Mekas’s filmic tribute to Verdi’s Messa da Requiem (1874) acquires a new affective power in light of a life spent as an émigré.

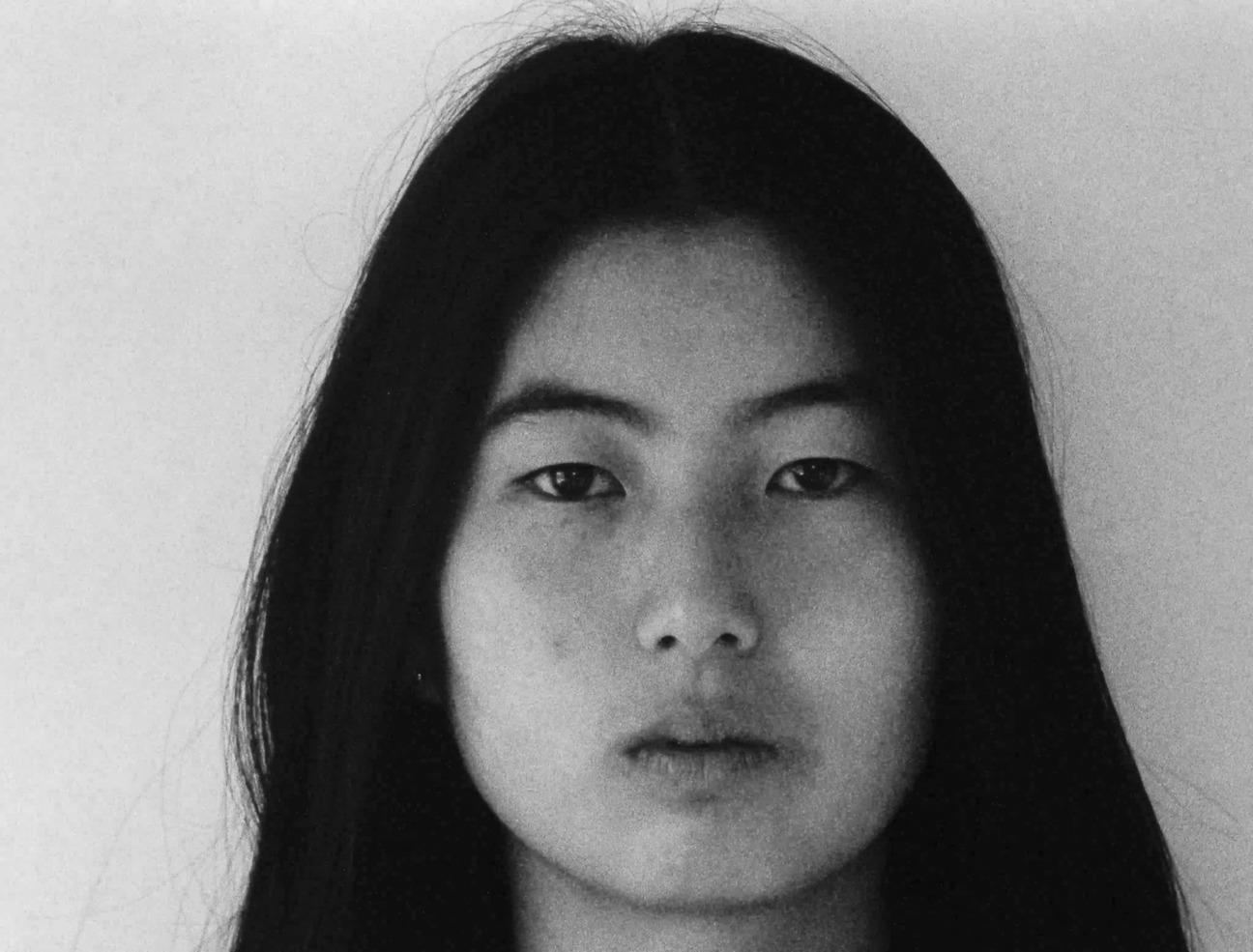

This final film differs from his best-known diaristic works, which document a life in exile and the New York avant-garde scene, in the near total absence of human figures. The few people who do appear in Requiem are filmed from afar and seem to be ghostly and peripheral, evoking feelings of alienation, impermanence, and mortality. The primary imagery of the film—flowers—comes from footage Mekas captured over three decades, using video and digital media from an early Sony camcorder to a pocket-sized Nikon. These cut flowers, garden blooms, wildflowers, and trees in full blossom are stitched together through his signature nonlinear editing, based on intuitive and rhythmic connections between the shots.

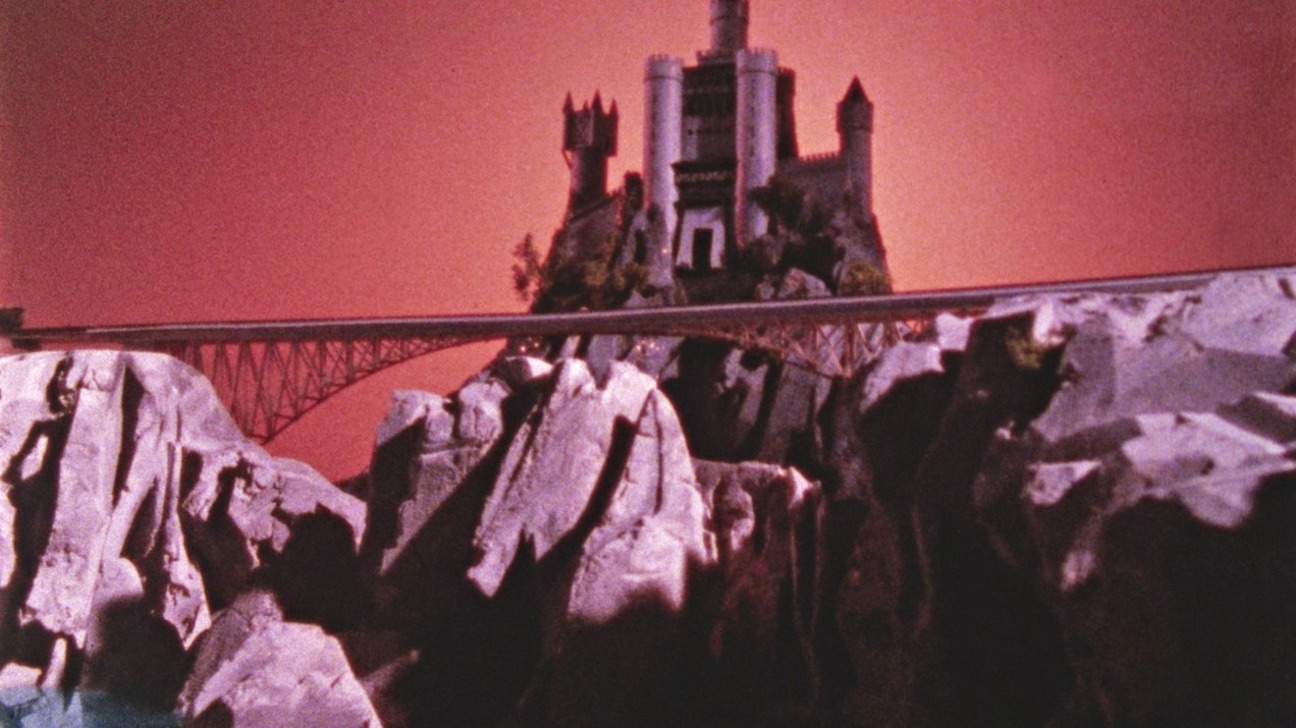

Periodically, these handheld shots of blossoms, petals, leaves, and stems are intercut with disturbing footage of disasters recorded directly from photographs, newspaper clippings, and television screens. The artist’s hand occasionally appears in front of his camera, obscuring these images of calamity and suggesting a personal repudiation of mass-mediated violence—a form of iconoclasm, perhaps. By juxtaposing the serene beauty of nonhuman nature with the spectacle of human catastrophe, the work reflects on the inherent dualities of a period marked by the realization that our experience of nature is inseparable from our harmful impact upon it. It is no longer possible to encounter a pristine, untouched natural world.

The replacement of Mekas’s distinctive voiceovers—a feature of his previous diary films—by Verdi’s Requiem makes this the most introspective of his works. Just as Verdi’s music moves between terror and solace, so Mekas’s images set the beauty and fragility of life against a chaotic backdrop of wars, genocides, and natural disaster. The effect is enhanced by the setting, which enhances the pervasive sense that this is as much an act of celebration as of mourning, intertwining reflections on mortality and expressions of hope. By presenting beauty and suffering as inextricable, this final reflection on the transient beauty of existence is both a lament and a call for change, a prophetic vision of a world poised for renewal.

From Jonas Mekas, “Gėlių kalbėjimas” (“Talking of Flowers”), published in Lithuanian, in Jonas Mekas. Poetry, ed. Julius Ziz (Vilnius: Odilė, 2021), 106. Translation by the author.