In 2009, the curator, filmmaker, and writer on visual culture Ariella Aïsha Azoulay visited the archive of the International Committee of the Red Cross (CICR) in Geneva to look at photographs taken in Palestine during the years 1947–50.1 Azoulay had already worked extensively in the Israeli state archives, creating from these another archive which she called Constituent Violence 1947–1950 (first published in book form in 2009), and hoped that the photographs held by the CICR would be somewhat different from those she had, in her words, “been able to view in Zionist archives.”2

These are the years of the establishing of the state of Israel, of course, and of the Nakba, or “catastrophe,” the violent displacement of approximately half the Arab population in Palestine—around 750,000 people. While the CICR had been present “at places in Palestine where massacre, expulsion, and destruction had taken place,” they had relatively few photographs, and most of these were not taken during the Nakba. Indeed, many of them were similar, though not identical, to those seen by Azoulay in Israeli archives—the same people, the same place, the same ongoing event, but just shown from a slightly different angle, a slightly different point of view.

But only slightly different. And as we now all know, what a photograph shows and what it is said to show may not be the same. During Azoulay’s visit, the CICR was insistent that it was a “neutral” organisation. But they also insisted that she could not reproduce any of the photographs without the captions which had been attached to them when they were placed in the archive; captions which reflected the interests of those invested in the creation of Israel and in the destruction of Palestine. Those who appear in the photographs were used to tell a story, though they could not use the photographs to tell their own.

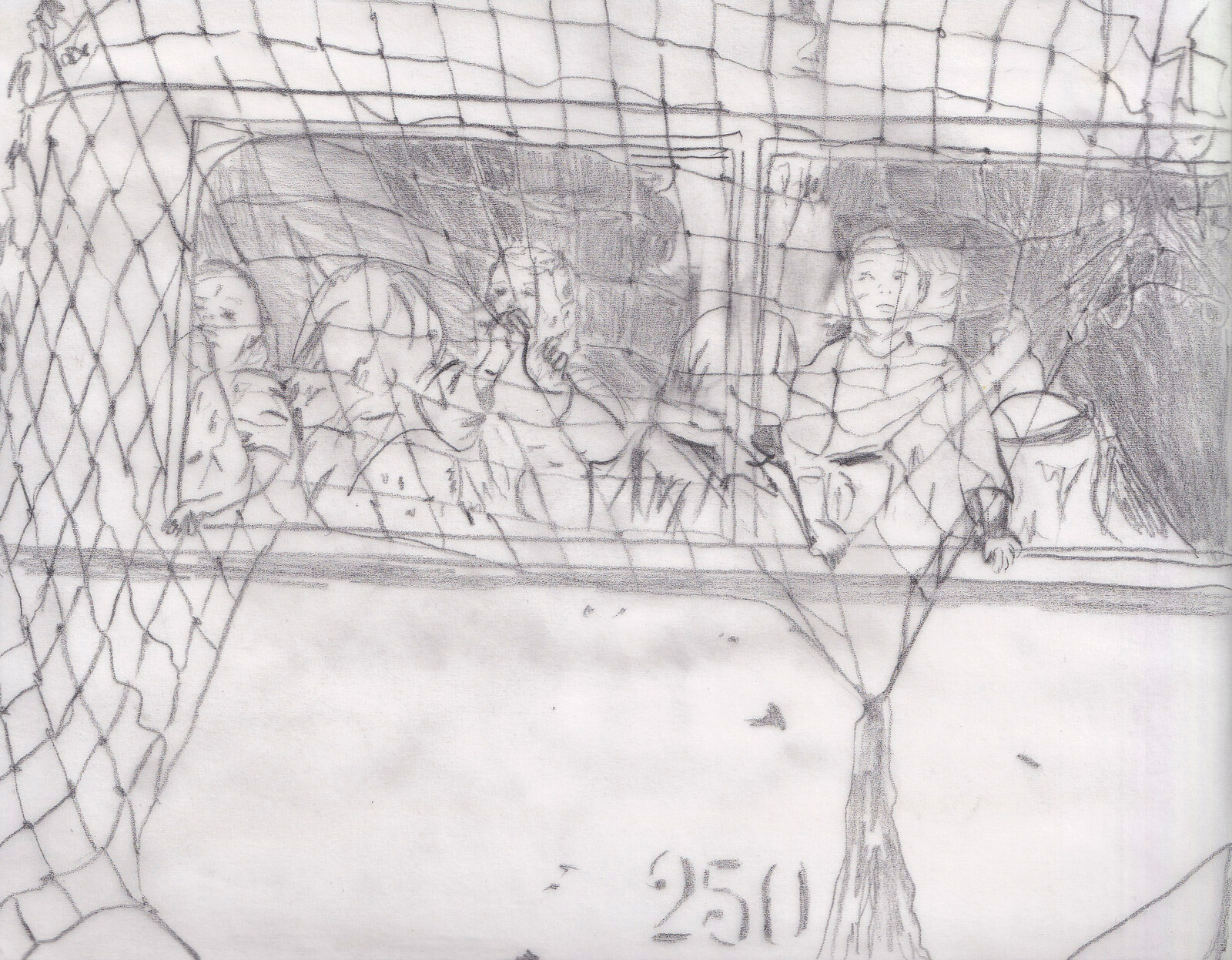

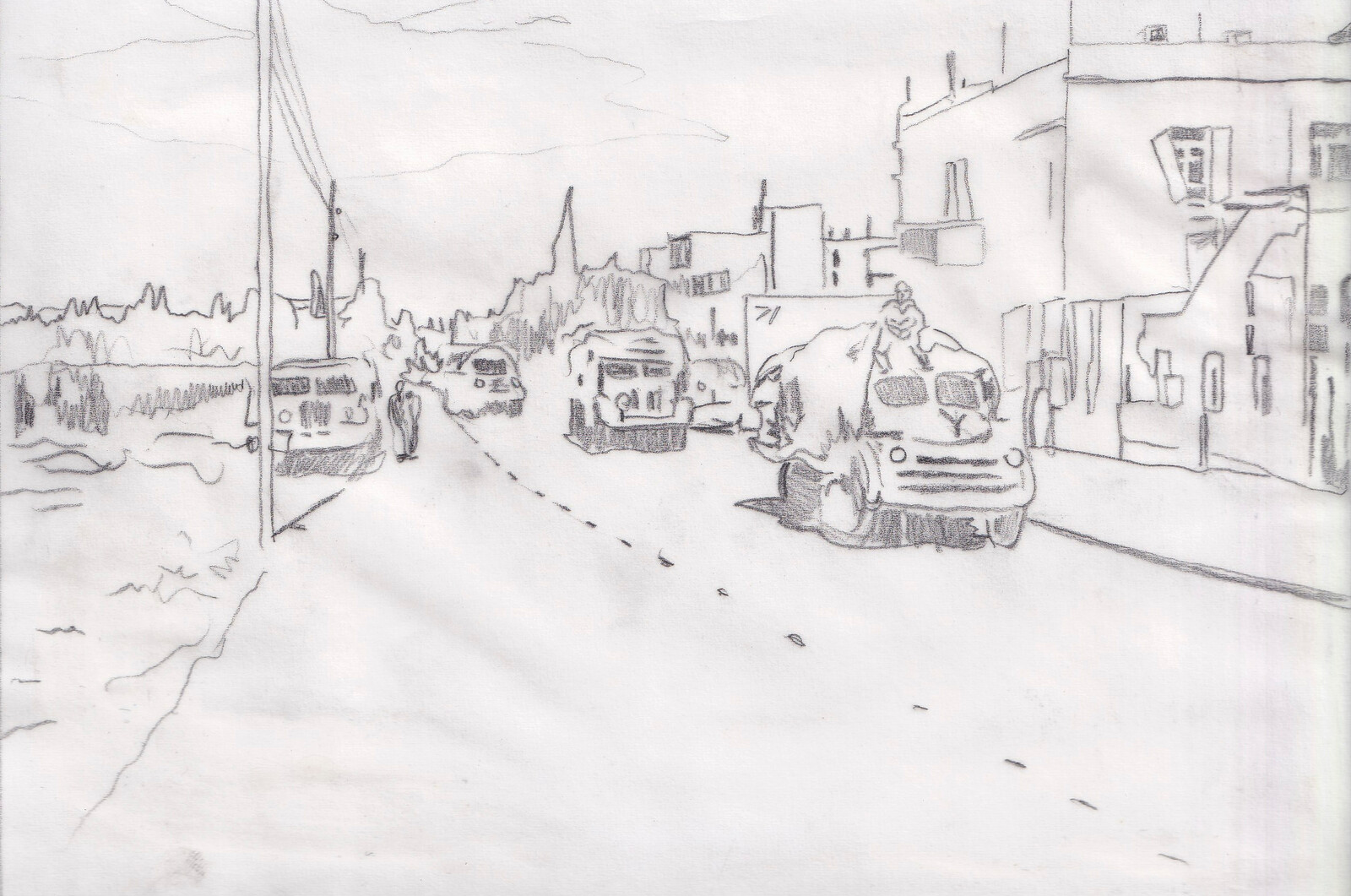

Azoulay selected 25 photographs from the 600 she had been shown, and made pencil drawings of them (reproduced here as prints to “acknowledge their photographic nature”). They appear to have been lightly traced, the outlines of people, suitcases, and carts clear but not firmly insistent, the shading sometimes more so, events thrown into stark relief under an unforgiving sun. Below these “unshowable photographs,” and held also in window mounts, she added her own rather more interrogative captions, which ask questions of what is shown and not shown, and which the “truth” of the archive omit wholly.

“How could the term repatriation be used in a description of this situation of clear expulsion?” Azoulay asks in one of her captions. “In what homeland exactly are the Palestinian women ‘repatriated’ as they are being driven across the borders of the new state that has just been founded in their homeland?” The plain white mounts are held in simple frames of dark scarlet, as if a red cross had been pulled apart in opposite directions. The unshowable photographs, with captions, were included in “Intense Proximity,” Okwui Enwezor’s ethnographically inflected 2012 edition of the Paris Triennial; twelve years later, they are now included in the second Bristol Photo Festival, a new biannual exhibition organised by IC Visual Lab, a local non-profit arts organisation which explores how images tell stories in and of the world.

In November, 2012, only a few months after the Paris Triennial closed, Israel launched “Operation Pillar of Cloud,” an eight-day assault during which time (according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) 174 Palestinians were killed, and many hundreds more injured or displaced. This current exhibition takes place during the ongoing destruction of the Gaza strip, and the daily killing of Palestinian civilians by Israeli forces. In the week between the exhibition opening and my visit, the official UN figure for Palestinian fatalities rose by over 300, to 42,718, half of them women and children—the actual number is undoubtedly far larger.

In her Edward W. Said lecture at Columbia University, delivered in late September 2023, the British-Palestinian writer Isabella Hammad remarked that the most we might hope from the novel is “not revelation, not the dawning of knowledge, but the exposure of its limit.”3 Despite the targeted killing of journalists and aid workers in Gaza, there is no lack of images of the killing of Palestinians—TikTok and Instagram have seen to that. How many more Palestinians will be seen burned in their hospital beds, crushed beneath their tents, before the exhibition comes to an end later this month? We do not need the crimes made any more visible—they are, horribly, insistently. Rather, how might they be made legible? This is what is asked in Azoulay’s work with photography—and perhaps answered in her thinking, in her writing, and in tender, raging exhibitions such as this.

Born in Tel Aviv, Azoulay defines herself as “an Arab Jew and a Palestinian Jew of African origins.” See Sabrina Alli’s interview, published online in Guernica, March 12, 2020: https://www.guernicamag.com/miscellaneous-files-ariella-aisha-azoulay/.

The images, captions, and an introductory essay from which the quotations in this piece are taken is included—alongside a recent interview with Azoulay—in an accompanying publication, pointedly titled Different Ways Not To Say Deportation (Bristol: IC Visual Lab, 2024).

Isabella Hammad, Recognizing the Stranger (London: Fern Press, 2024), 45.