Sheba Chhachhi’s photographs, taken on the frontline of the Indian women’s movement—crisp black-and-white images of working-class women at a demonstration, performing in a play about gender-based violence, and in their own homes—encapsulate this watershed exhibition well. “The Imaginary Institution of India”—which includes over 150 works of painting, sculpture, photography, and other media, sprawling over two floors and thirteen sections—is a show about class and its tensions, playing out violently in the world’s largest democracy. Curator Shanay Jhaveri’s thesis, though, rests on the formal and aesthetic shifts as shaped by the politics of this time period (1975–98). For Jhaveri, developments in landscape painting, for example, illustrate the ways in which class tensions came to a head after the declaration of Emergency in 1975.

Writing in March 1987, artist Anita Dube asked whether the incumbent Indian nationalist and mainstream political discourse could view the lower caste person and petit bourgeois artist as a “species being who creates history.”1 “A sleepless wind is raising a sleepless song in sleepless heads in sleepless nights,” wrote Dube at the end of her text. Reading it, I paused on every sleepless, and again at sleepless nights. If sleepless nights paint a picture of dreaminess, it is challenging to return to the sleeplessness of a moment full of rage, animosity, hatred, and anxiety. In May 1987, the Hashimpura massacre of dozens of Muslim men by Indian police took place near Meerut in the state of Uttar Pradesh. In the same year, the Union Territory was split and Goa became its own state; the Defense Minister of India, V. P. Singh, resigned, Margaret Thatcher was re-elected as British Prime Minister, and conflict was emerging between China and India.

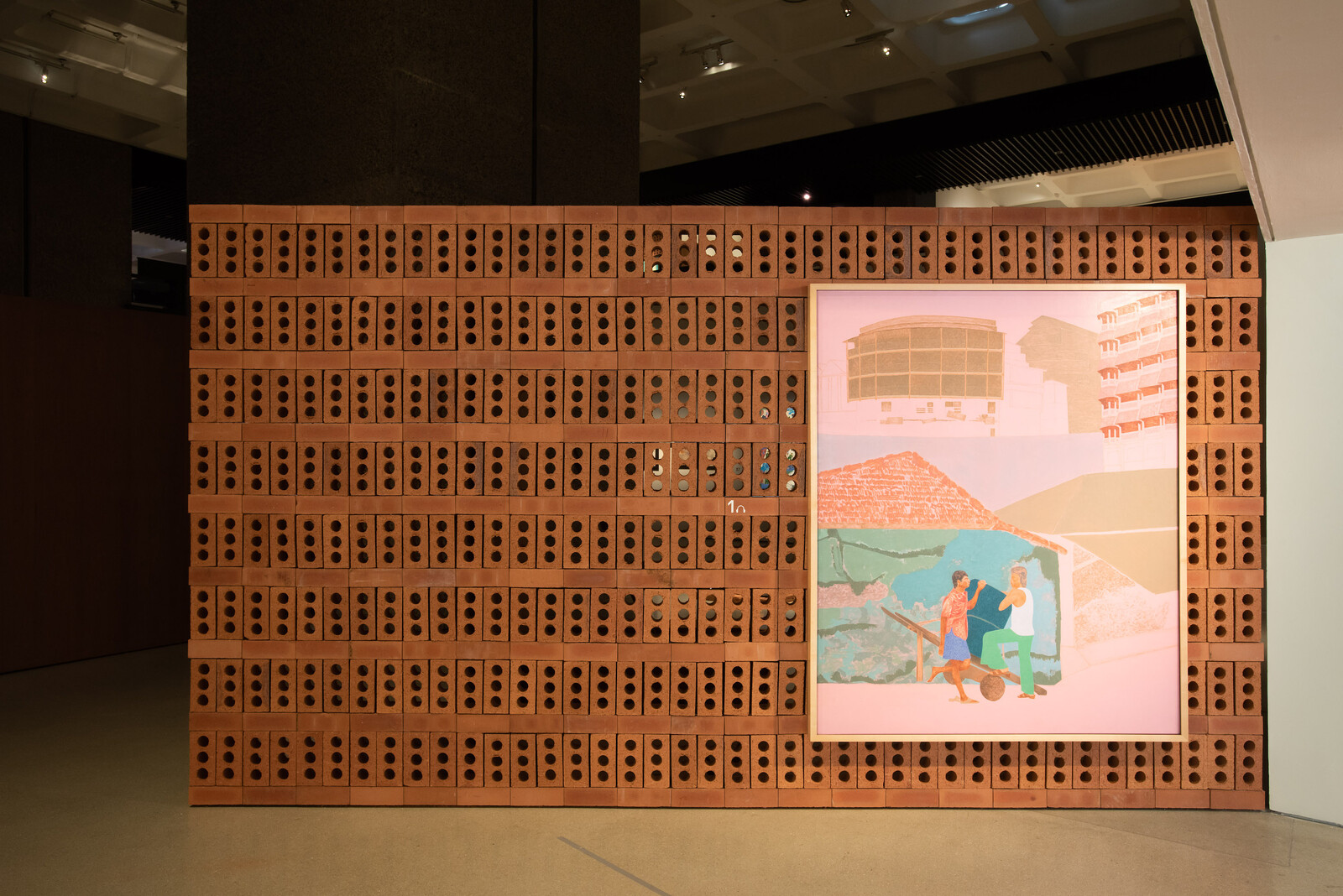

If Indian artists have always been considered “cosmopolitan,” it’s perhaps because we tend to think of their migration outside of India towards Europe and the Americas: Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore reading law in London in the 1870s, or the world citizenship of Vikram Seth.2 The significance of an individual artwork or single art career when cast against the broader history of India can be fickle. Looking at “The Imaginary Institution of India,” I was propelled to consider the migrations and movements of artists within India itself: the circulation across time and place of artists, their works, and their ideas. For example, what is the link between the Indian Radical Painters’ and Sculptors’ Association in Baroda and Kerala? One of its members, K. P. Krishnakumar, was born in Kerala in 1958, and lived and worked in Baroda during the 1980s. The exhibition guidebook states that the Radical Group disbanded after his death in 1989, yet posthumously, his stature has increased across the country: Krishnakumar’s monumental sculpture was displayed at the inaugural Kochi Biennale in 2012, while his artwork is now in the permanent collection of the Kiran Nadar Museum, a major partner of the exhibition, in New Delhi.3

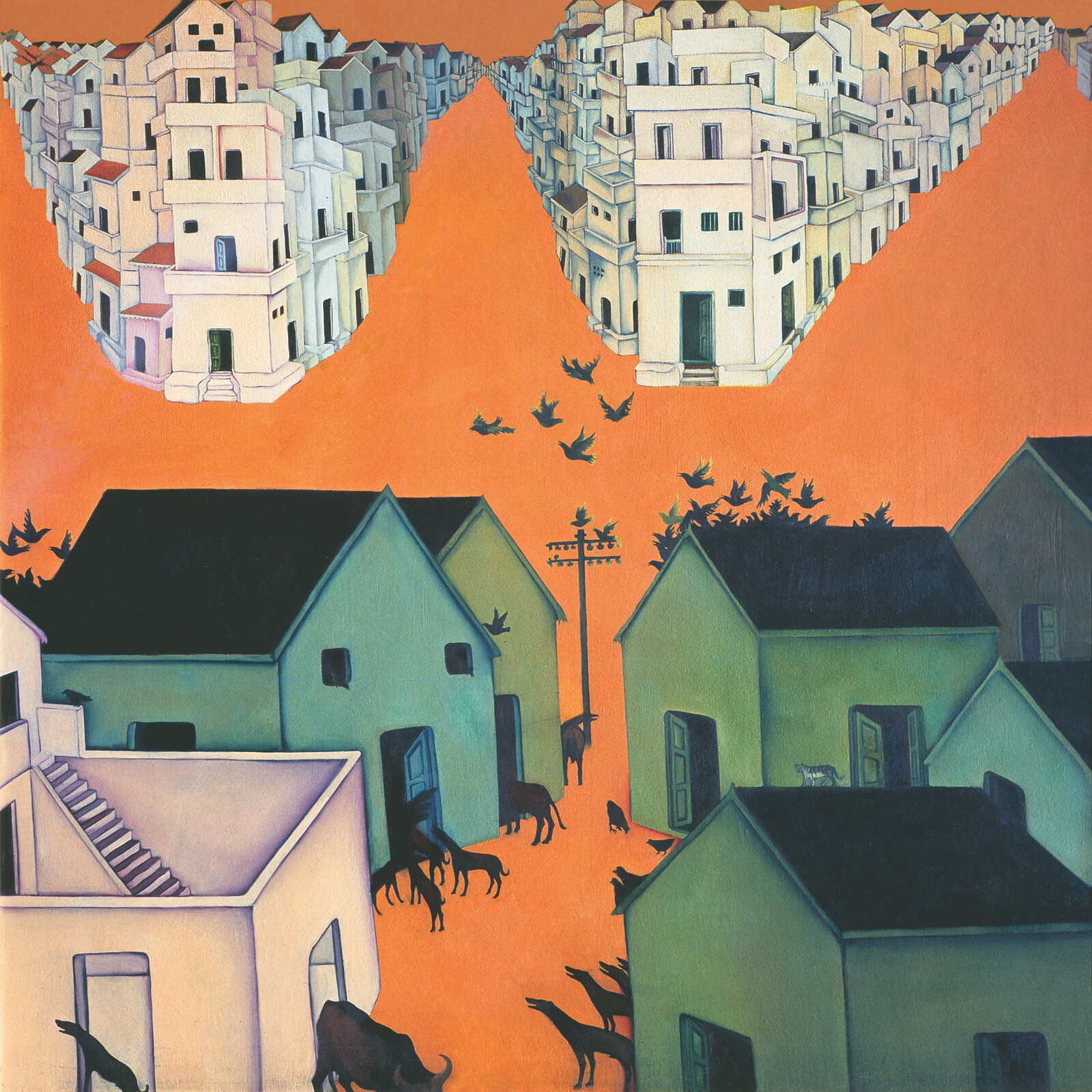

A number of artworks in the show reflect the tension and outburst of religious violence towards Muslims in 1987. The titular question of Gulammohammed Sheikh’s painting How Can You Sleep Tonight? (1994–95) evokes the horror that Muslims in India faced after the 1992 Hindu-led destruction of Babri mosque in Ayodhya. The painting’s angular perspective recalls Art Deco aesthetics, and visually relates to German painting and, to this viewer, is reminiscent of the work of Archibald Motley, if only for its nocturnal views; it depicts fire, gun violence, and a world upturned. Bright yellows of fire contrast with dark purples of smoke-filled night sky.4

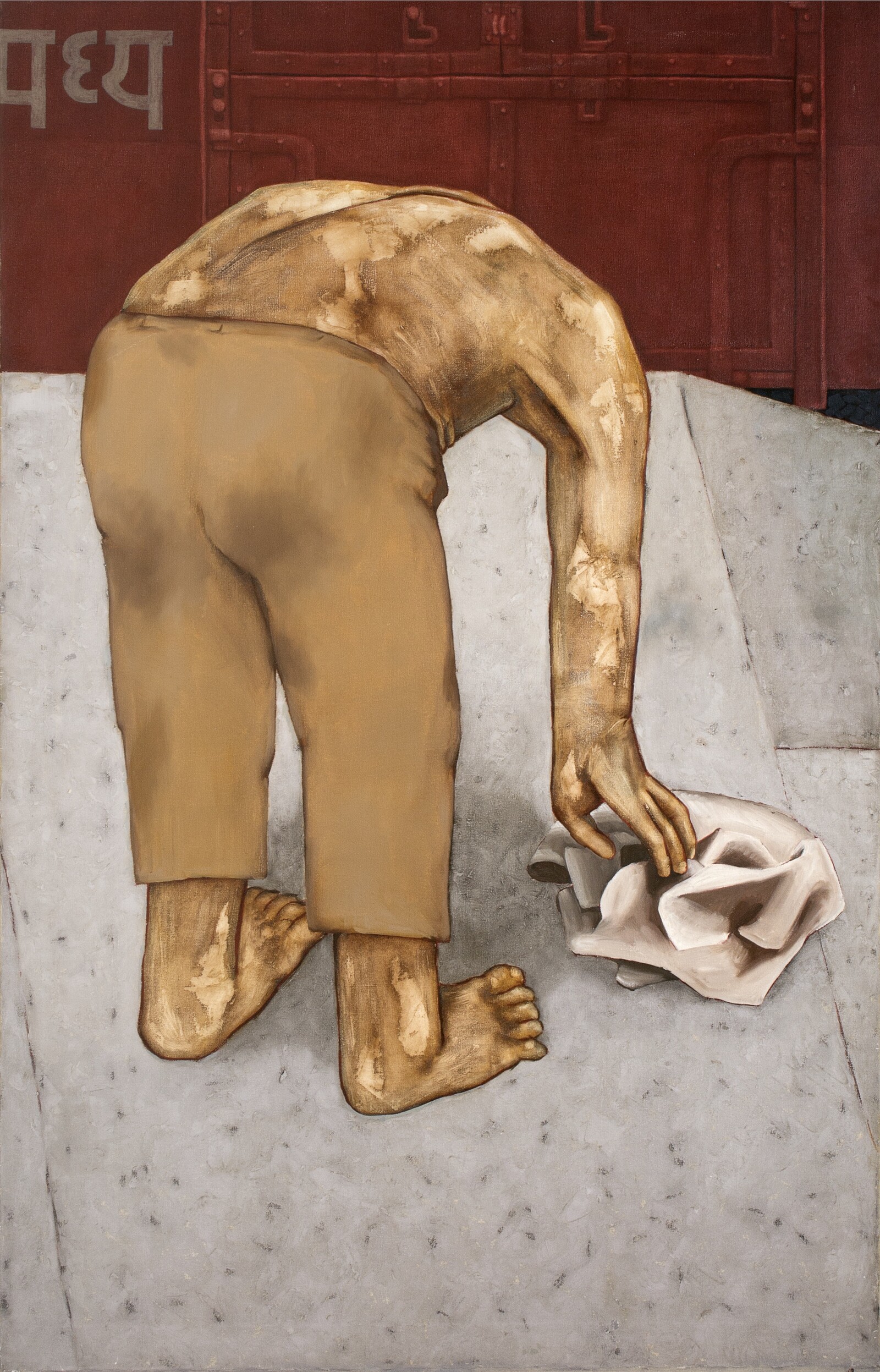

Gayatri C. Spivak tells us that these tensions were always present: that in 1946 Kolkata, neighboring Hindus and Muslims had lived in a conflict-ridden coexistence for centuries. Kolkata, Spivak writes, was “among the cruelest sites of the Hindu-Muslim violence. It was a politically mobilized violence. The country was going to be divided, and so people with whom we had lived forever, for centuries, in conflictual coexistence, suddenly became enemies.”5 Those religious tensions, accentuated in the aftermath of partition, are at the center of this serious exhibition that introduces its viewers to the immediate issues of leadership in post-1950 India (protagonists include Indira Gandhi, daughter of anti-colonial nationalist Jawaharlal Nehru, and her son Rajiv Gandhi). We see workers everywhere, carrying weights, crossing bridges; we see them in landscapes, and beyond the landscapes; we see them alone or in groups, such as in the paintings of Sudhir Patwardhan (Overbridge, 1981 and Town, 1984), and Gieve Patel (Two Men with Hand Cart, 1979 and Off Lamington Road, 1982–86). Even though landscapes had been part of Indian art for decades ( an echo of Turner and Constable from the British art curriculum), they take on a different meaning here. In a spoken introduction (published on the gallery’s website) Jhaveri stresses the emptiness, desolate, and angular nature of Sheikh’s painting Speechless City (1975). In Sheikh’s art, sleeplessness turns into speechlessness.

Jhaveri’s is a historiography that takes seriously the social fabric of India, a phrase that I borrow from philosopher Sundar Sarukkai. He argues, following B.R. Ambedkar, that democracy lies not merely in jurisprudence, but rather in the social spaces and quotidian experiences of peoples of the country.6 The landscapes of Gulammohammed Sheikh, Sudhir Patwardhan, Bhupen Khakhar, and Gieve Patel, all of whom focus on the quotidian, come to mind. Similarly, The Indian Radical Painters’ and Sculptors’ Association were motivated by the leftist politics of Kerala, where the Communist Party of India was founded in 1939. A politics of the left was developed, but one which implies that this region of Kerala was at odds with the Indian nationalists. As Sarukkai argues, the country’s true democratic protocols exist within its social fabric: an idea the Radical Group took seriously.

This exhibition views history from below: its radical, everyday conception of democracy includes feminism and anti-caste activism, too. Savindra Sawarkar’s etching Untouchable, Peshwa in Pune (1984), is a stark reminder of the ongoing caste prejudice in the country and its diaspora. Sheba Chhachhi’s scintillating and revelatory documentary images show that the so-called “third world women’s movement” was not at the periphery but rather at the center of the agitation during the years following the Emergency. That agitation has often been made out to be a hindrance to the functioning of democracy: as the show insightfully suggests, it may rather be a sign of its health.

In her accompanying text for the exhibition of the Indian Radical Painters’ and Sculptors’ Association titled “Questions and Dialogue” held at the Faculty of Fine Arts Gallery in Baroda.

See Ranjit Hoskote, “Histories Written Across the Waters,” in Every Step in the Right Direction: Singapore Biennial 2019 (Singapore Art Museum, 2019), 24–31.

See Shankar Tripathi, “Revolutionaries of Indian Art: Revisiting the Kerala Radicals Today,” DeCenter Mag, https://www.decentermag.com/culture-kerala-radicals.

Archibald Motley was influenced by European abstract modernism, though no direct reference exists between Motley and the artist Gulammohammed Sheikh. See Sharon F. Patton, African-American Art (Oxford University Press, 1998), 136–138.

Gayatri C. Spivak, “Nationalism and the Imagination” in An Aesthetic Education in the Era of Globalization (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012), 277.

Sundar Sarukkai, The Social Life of Democracy (Kolkata: Seagull, 2024), 1–10.