October 9–November 9, 2024

If there was one exhibition that tapped into the Tunisian zeitgeist during Jaou, the contemporary art biennial organized in Tunis by the Kamel Lazaar Foundation, it was “Hopeless.” Curated by Chiraz Mosbah on the grounds of Club Aviron Tunisois, with storehouses for kayaking and rowing perched on the edge of the water, the show references a desire among many young Tunisians to leave the county, given its struggling economy and increasing authoritarianism, and its position as a crucial crossing point for clandestine migrants. Still, works by some forty photography students from sixteen academic institutions in Tunisia, who collaborated on the curatorial design and theme, expressed a commitment to place in their staging across the site’s closed and open spaces.

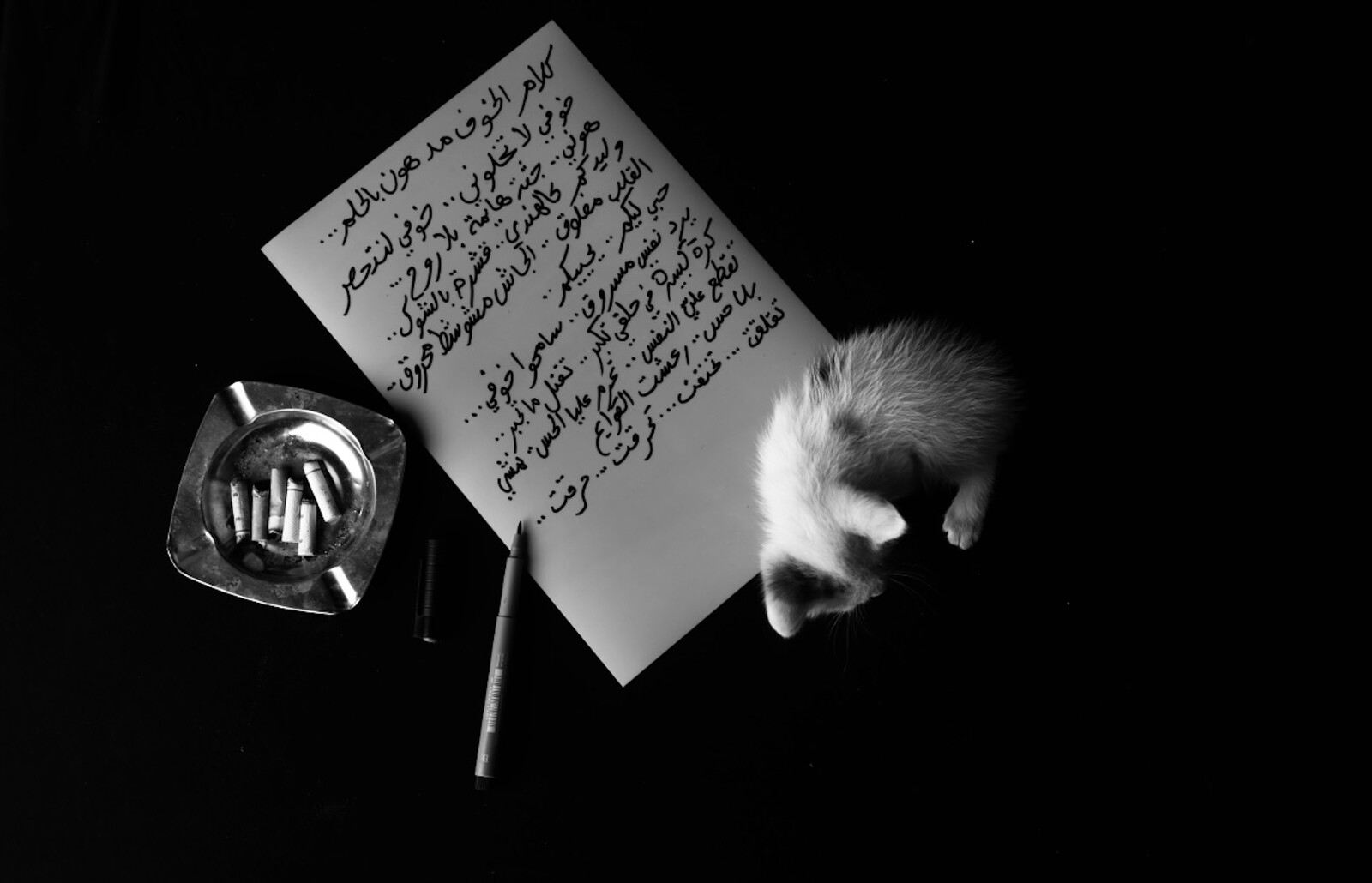

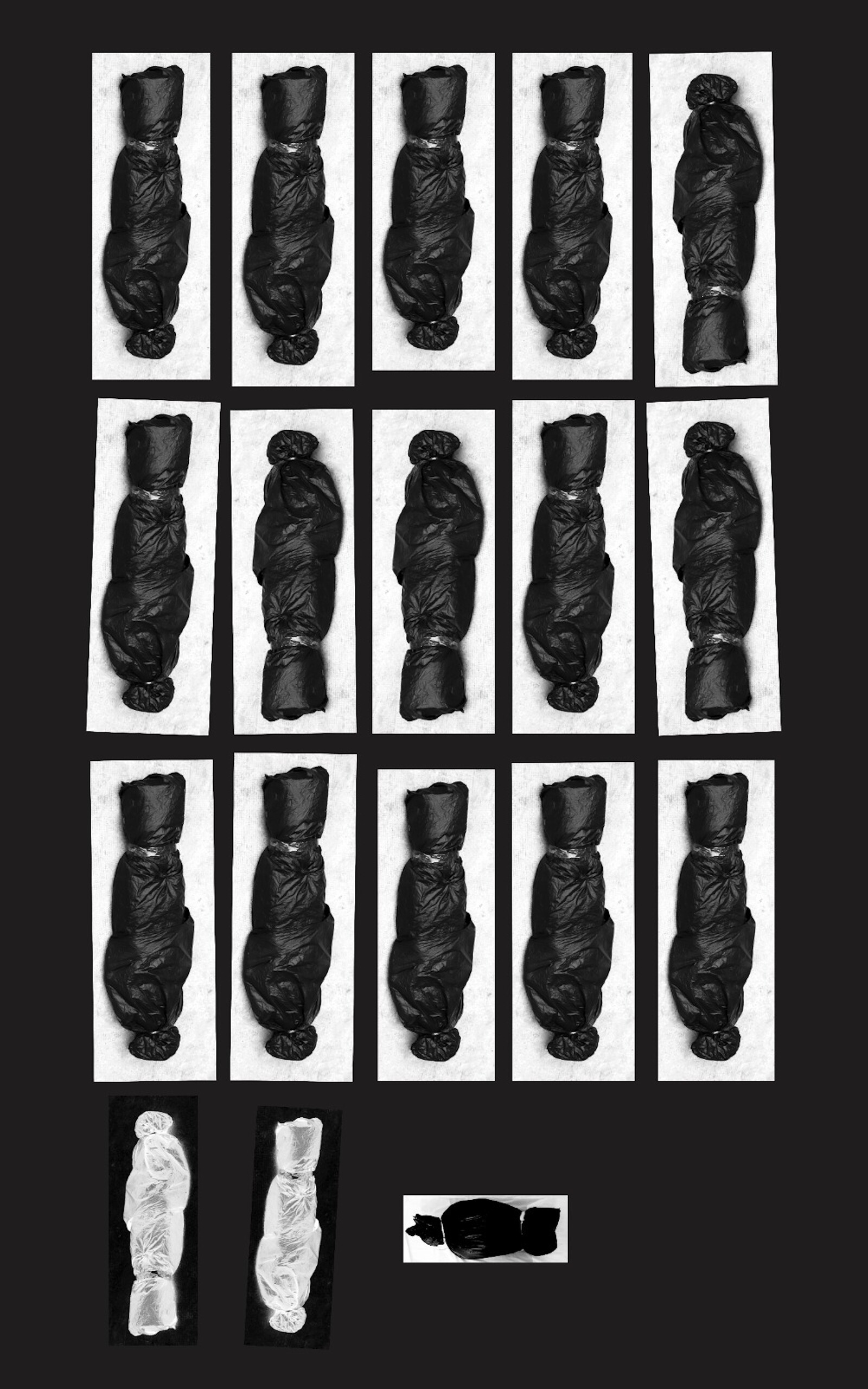

In one room, Last Words (2024) by Souhir Ben Abdallah consisted of a black-and-white photograph of a letter by a young man describing his fear of being trapped, ostensibly explaining his desire to leave the country, and an audio recording of his words being read aloud. In an adjacent space, where images were viewed using flashlights in the dark, photos by Dhia Guermit were installed amid stored oars, including one showing a trio launching a rowboat into the sea. Nearby, a digital print by Samar Tahri lined up body bags in three rows by five with two inverted white forms at the bottom, alongside a child-sized swathing. The title, 18/18 (2024), references an incident on the Zarzis coast, when a boat carrying eighteen people capsized, leaving no survivors.

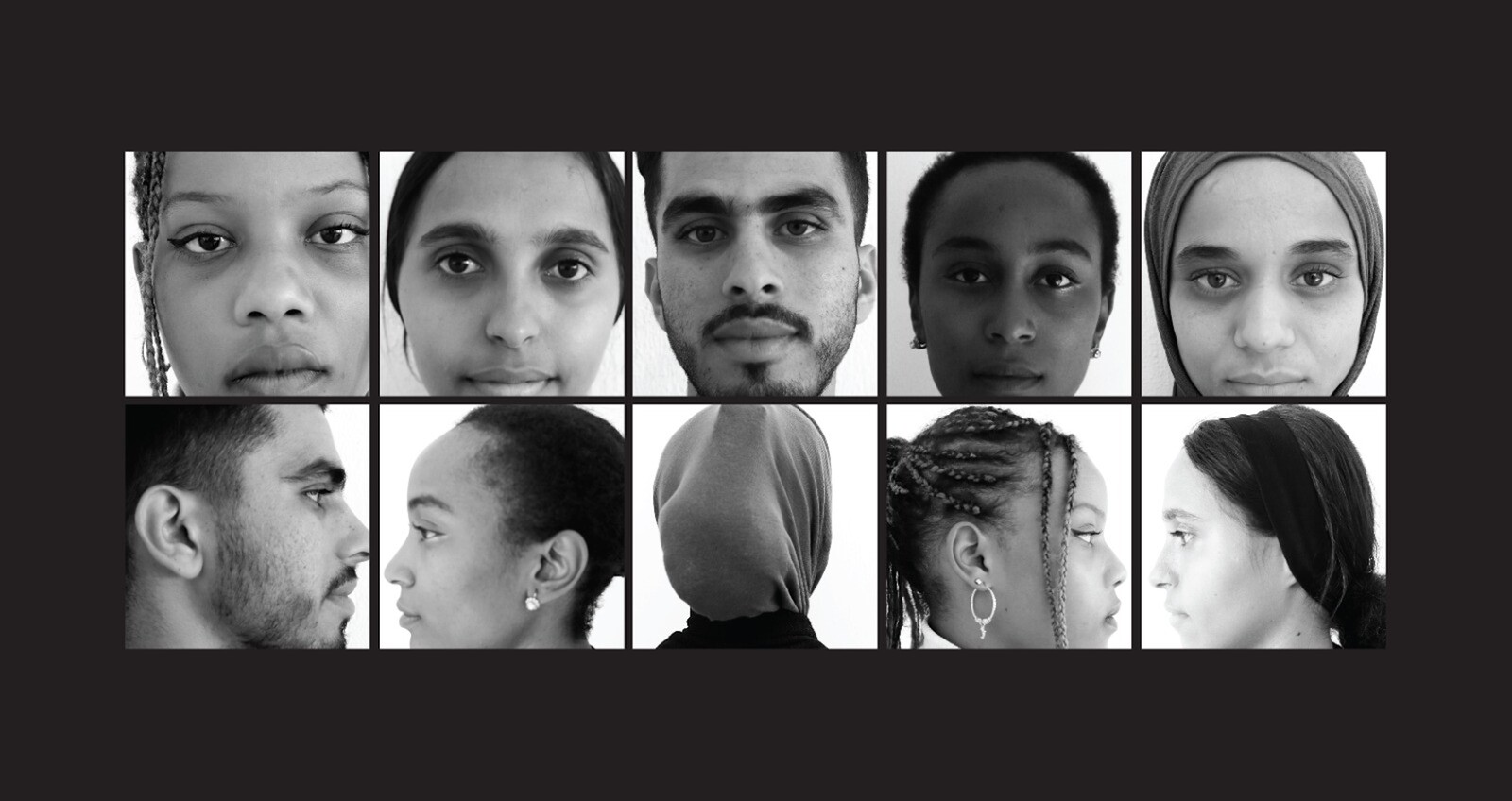

A sense of solidarity resonated across “Hopeless,” as demonstrated in works like Ouns Yajini’s close-up portraits of migrants, This is not a criminal (2024), in keeping with the theme of resistance as a form of love for Jaou’s seventh edition. That theme was palpable in Bachir Tayachi’s solo show “In My Room,” held in a warehouse next to the multidisciplinary space B7L9, where Gabrielle Goliath’s ongoing audiovisual installation project foregrounding testimonies of patriarchal violence, Personal Accounts, was screened. Billed as a three-part queer odyssey, In My Room is a Gesamtkunstwerk composed of new commissions (all 2024) reflecting Tayachi’s evolving relationship with his queer identity, starting with fuck men, an outstanding video montage that rages against the conditioning of idealized heteronormative masculinity in pop culture, and concluding with a disarmingly vulnerable untitled video of the artist and an ex-lover coming to terms with the traumas that contributed to their relationship’s demise. Given the Tunisian government’s persecution of LGBTQ+ communities, the exhibition’s opening night was a galvanizing and moving affair, with Tayachi’s community showing up to support the artist alongside allies from across the city and further afield.

There were expressions of solidarity, too, at the packed opening of Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme’s “The Song Is the Call and the Land Is Calling,” an exhibition staged in a warehouse close to the former stock exchange, housing three works, including the multi-channel audio-visual installation May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth: Only sounds that tremble through us (2020–22). Departing from archival footage they started collecting online during the Arab uprisings that began in Tunis in December 2010, and including video taken in the West Bank of performers recreating gestures from that archive, this was a poignant first presentation for the artists on the African continent. Especially given the support for the Palestinian cause among Tunisians and growing fury at Israel’s ongoing assault on Gaza, the West Bank, Lebanon, and now Syria. That audacious violence—which intersects with crises in Sudan, the Congo, and elsewhere—has highlighted the uneven distribution of freedoms and oppressions across global space, as well as the divides that exist between governments and populations, given how mentions of Palestine have been censored in the West and elsewhere, despite the world’s highest institutions calling Israel out for its obscene disregard of international law and British and American opinion polls showing overwhelming support for a ceasefire. These political betrayals have amplified the urgency to imagine a collective future that is, as political scientist Françoise Vergès put it during the Jaou symposium organized by Les Chichas de La Pensée, “postracist, postimperialist, postpatriarchal, and really, really postcolonial.”

Stirrings of that future emerged in “Unstable Point,” a public exhibition installed on scaffolding stretching down a section of Avenue Habib-Bourguiba’s central promenade. Drawing on Stuart Hall’s assertion that “Identity is formed at the unstable point where the ‘unspeakable’ stories of subjectivity meet the stories of history, of a culture,”1 curator Taous Dahmani selected twelve artists from an open call. The result was a reflection on identity as a condition of perpetual becoming in the context of colonialism and its after-effects, where individuals shaped by historical entanglements cannot but exceed national borders. Take Farren van Wyk’s Mixedness is my mythology (2020–ongoing), featuring the artist and her siblings in striking photographic portraits that synthesize a family history bridging South Africa and the Netherlands via colonization with a contemporary, international pop culture fuelled by American film and music. Or Ilias Bardaa’s Maghrébine (2023), which lays out black-and-white portraits of individuals from the North African diaspora in Europe with text describing their lives over a billboard-sized map of the Maghreb. Making a case for the reformulation of the nation-state construct, the historic instrument of colonialism with its toxic nationalisms, works like these open up what van Wyk calls “a gray area,” in the exhibition text, “where we have the freedom to visualize how our cultures organically merge.” There must be a future in that freedom.

See Stuart Hall, “Minimal Selves,” in The Real Me: Postmodernism and the Question of Identity (ed. Lisa Appignanesi), (London: ICA, 1987), 44.