On the Harvard campus, relics of Germanic high culture are never far away: a bronze replica of a medieval lion sculpture from Lower Saxony graces the courtyard of Adolphus Busch Hall, named for an émigré who made his fortune selling—what else?—beer and diesel engines. A counterpoint to that building’s historicist opulence can be found in the sober Modernism of the Law School’s graduate dorms designed by a team led by Walter Gropius during his tenure at the university. As ciphers for rigor, perfection, and intellectual prowess, mythical versions of Germany are deployed as fodder for the Harvard myth itself.

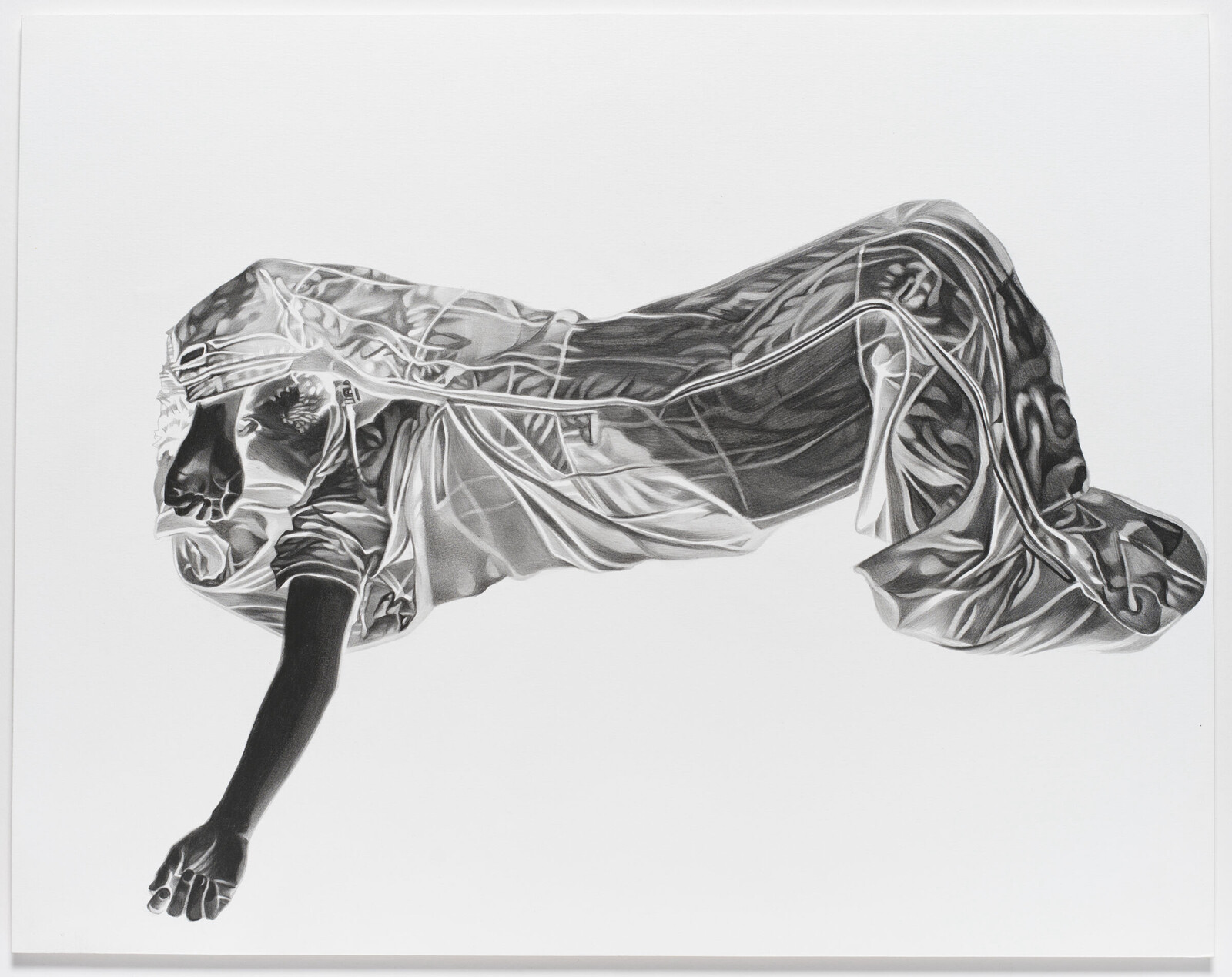

“Made in Germany? Art and Identity in a Global Nation,” at the university’s Busch-Reisinger Museum, adds a further chapter to this transatlantic double vision, focusing on art since 1980 from the GDR and the Federal Republic (FRG). However, national myth-making here gives way to an astute selection of artworks that pry open the cracks in a state that defines belonging foremost through adherence to cultural and linguistic standards, evident in the language and knowledge test that immigrants must pass for naturalization. “Made in Germany?” coaxes out the tense dialectics between a nation’s openness towards outside cultures and economies, and the nationalist rejection of that same openness, through artworks by twenty-three artists, including Hito Steyerl’s rarely seen student film The Empty Center (1998), cast-concrete radio sculptures from Isa Genzken’s “Weltempfänger” series made in the eighties and nineties, and Marc Brandenburg’s hauntingly sleek drawings of unhoused people sleeping. The exhibition unites conceptualism with historical inquiry, a two-pronged approach that may itself count as an Exportschlager, a term favored by journalists and politicians to describe Germany’s most successful exports.

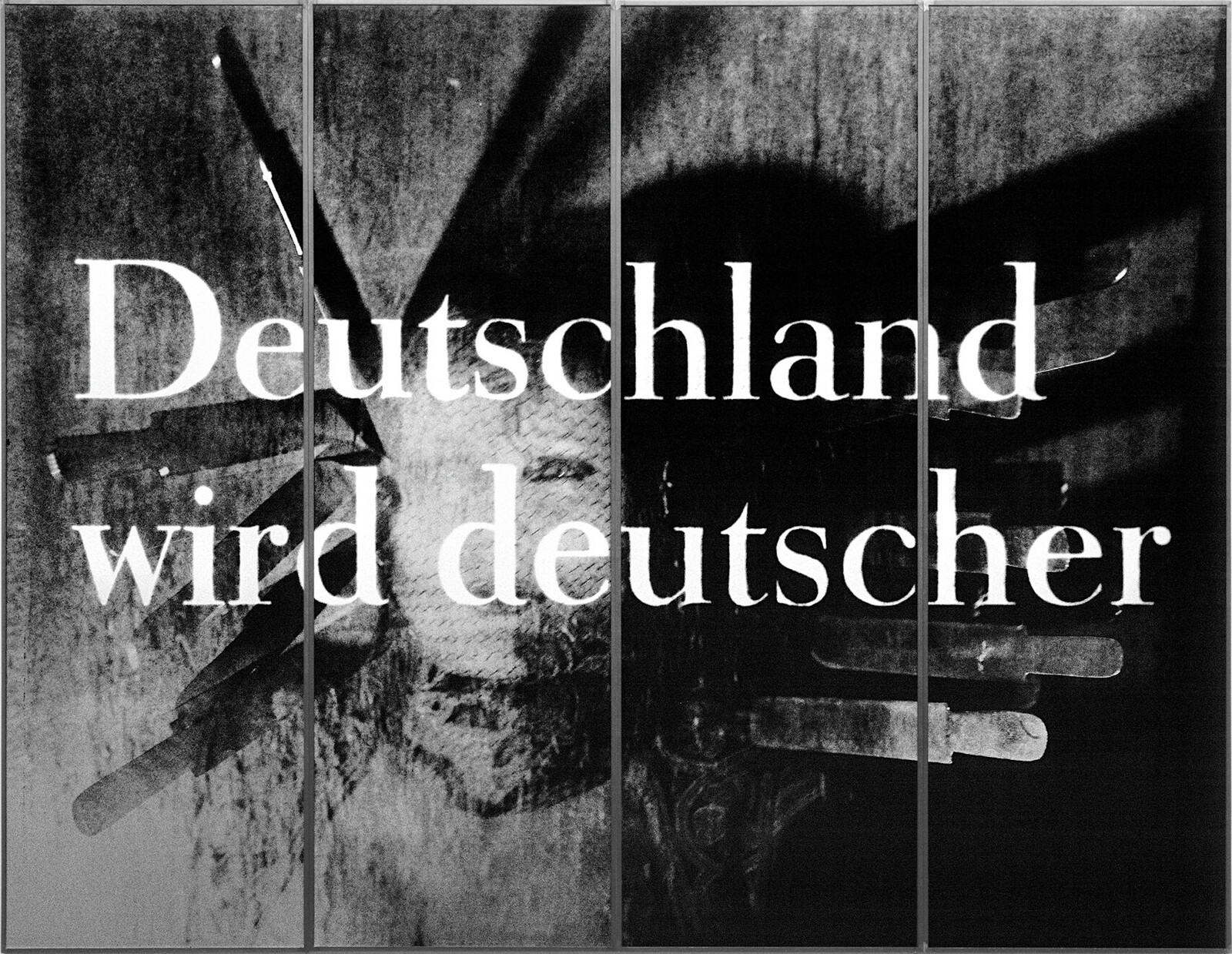

Upon entering, visitors face Katharina Sieverding’s Deutschland wird deutscher XLI/92 (1992), a black-and-white photograph created only a few months after several deadly attacks on refugees and immigrants shook the reunified country. Originally meant for exhibition in public spaces, the work spans four large aluminum panels that are imprinted with a blurry self-portrait. The artist’s face is obscured by a mesh-like veil and entrenched in a struggle between light and shadow, reminiscent of Weimar-era cinema. Throwing knives stick out from the wall behind her, marking the scene as a sinister circus game. The titular phrase Deutschland wird deutscher overlays the image, spelled out in the newspaper font of the center-left weekly DIE ZEIT. The English translation, “Germany becomes more German,” lacks the original’s ominous echoing of the xenophobic catchphrase Deutschland den Deutschen, “Germany to the Germans,” a phrase that was in the news again earlier this year when a video surfaced that showed party-goers at an elite club on the island of Sylt chanting this and other extremist slogans.

Deutschland wird deutscher fastens nationalist sentiment to gendered violence and the aesthetics of horror, thereby priming visitors for an exhibition that probes the centrifugal and often distressing forces inherent to a “global nation” at every juncture. Curators Lynette Roth, Peter Murphy, and Bridget Hinz have not only selected artworks that are formally and conceptually divergent, but also, thanks to careful arrangement in space, harnessed the thought-provoking counterpoints inherent to this curatorial selection. Sieverding’s imposing photograph, for example, is preceded by Sung Tieu’s installation Multiboy (2021) in the exhibition’s vestibule, which takes a delicate, analytical approach to the restraints placed upon Vietnamese labor migrants to the GDR. Multiboy is named after a popular food processor, made in factories that employed Vietnamese workers. Tieu has enclosed one of these bright-orange utensils in a steel cage. Three pages from a work contract are framed on the wall behind it, written in both German and Vietnamese and imprinted with a recurring pattern of modular steel fences, the kind that often circumscribe refugee camps, signaling enclosure into an enduring state of temporariness.

The pairing of Sieverding’s and Tieu’s works proposes a set of complementary contrasts: GDR and FRG, aesthetics of administration and aesthetics of provocation, the piercing immediacy of a xenophobic slogan and the bureaucratic convolution of a work contract. As visitors pass further into the exhibition, politics, history, and ideology also move inwards: Želimir Žilnik’s film Inventur-Metzstrasse 11 (1975, restaged by Pınar Öğrenci in 2021) is set in the hallway of a tenement building, where so-called Gastarbeiter or “guest workers”—foreign workers who were incentivized to move to Germany and alleviate postwar labor shortages—share one-liners about life in the country.

Elsewhere, Ulrich Wüst’s remarkable Hausbuch (1989–2010) serves as a photographic archive of found items from houses the artist purchased after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Many hours could be spent examining the details contained therein: an image of Johann Sebastian Bach, half-buried by dirt or plaster; a school child’s graph that charts the path from capitalism via imperialism to socialism. In Wüst’s leporellos, the material remnants of life become the archaeological artefacts of a national subconscious, imaginable as the images that haunt Sieverding’s tortured femme fatale. Henrike Naumann’s room-sized installation Ostalgie (2019) pushes the unhomely enfolding of ideology furthest. Her arrangement of boldly curved chests and furry lounge furniture evokes a host of desires, political beliefs, and repulsions, testimony of Naumann’s striking ability to give form to the contradictory pulls in the social and political fabric.

Despite its contemporary material, “Made in Germany?” is a deeply historical exhibition. The latest chapters on art, identity, and global nationhood are yet to be written: the dynamics of twenty-first-century migration, for example, or Germany’s relation to the state of Israel and its actions in Palestine and Lebanon, which would require critical consideration of Germany’s Erinnerungskultur, or memory culture. By teasing out a nation’s fears of its own fraying edges, the Busch-Reisinger Museum, a museum of art from German-speaking countries, purposefully erodes the “Made in Germany” brand its own collection is based on.