Widely recognized as a committed activist and an influential educator and mentor, Lala Rukh, who passed away at the age of 69 in 2017, was notoriously reticent about sharing her own art practice, its rigorous conceptualism, minimalist precision, and commitment to drawing placing her firmly at odds with prevailing trends in Pakistan. As the first major retrospective of her work, “In the Round” attempts to reconcile the fiercely embodied immanence of her politics and pedagogy and the transcendence of her art, which approaches the mystical through breathtaking formal economy.

Lala co-founded the Women’s Action Forum in 1981, a grassroots feminist organization established to challenge misogynist laws and policies introduced by the military dictatorship of Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq.1 This, and Lala’s other political activism, is presented at Sharjah Art Foundation through extensive archival displays that include photographs and videos from protests and conferences, testimonies from comrades, students, and friends, posters Lala designed and produced herself, and a screen-printing manual for activists (titled In our own Backyard) that she published in 1987 to counter the regime’s ban on independent printing presses. As the leader of a novel Master’s program at Lahore’s National College of Arts, Lala also introduced a curriculum that encouraged experimentation and interdisciplinarity, as seen in the facsimiles of syllabi and publications available for perusal. She also devoted time to the All Pakistan Music Conference, a platform for promoting and preserving Hindustani classical music co-founded by her father in 1959, which immersed her in this rich tradition from a young age. Photographs, CD covers designed by the artist, and an hours-long playlist of recordings from the early 1960s show this important vein of her multifaceted life and practice.

Lala was an enigma, and ciphers abound throughout her art. Made between 1983 and 1986—after completing a Master’s at the University of Chicago in 1976 and returning to Pakistan—the earliest art works in the exhibition turn the traditional studio exercise of life or gesture drawing (of a male model) on its head. Pared down to just a few short, barely visible lines, these untitled Conté crayon drawings capture not a held pose or gesture but the ineffability of the moments in between. They are representations not of a presence but of its memory: the body as apparition, a figure reticent and withdrawn. These works stand in contradistinction to the numerous representations of Lala peppered throughout the exhibition, from archival photographs and youthful experiments in photographic self-portraiture to a lyrical line drawing of the young artist by the modernist master Sadequain.

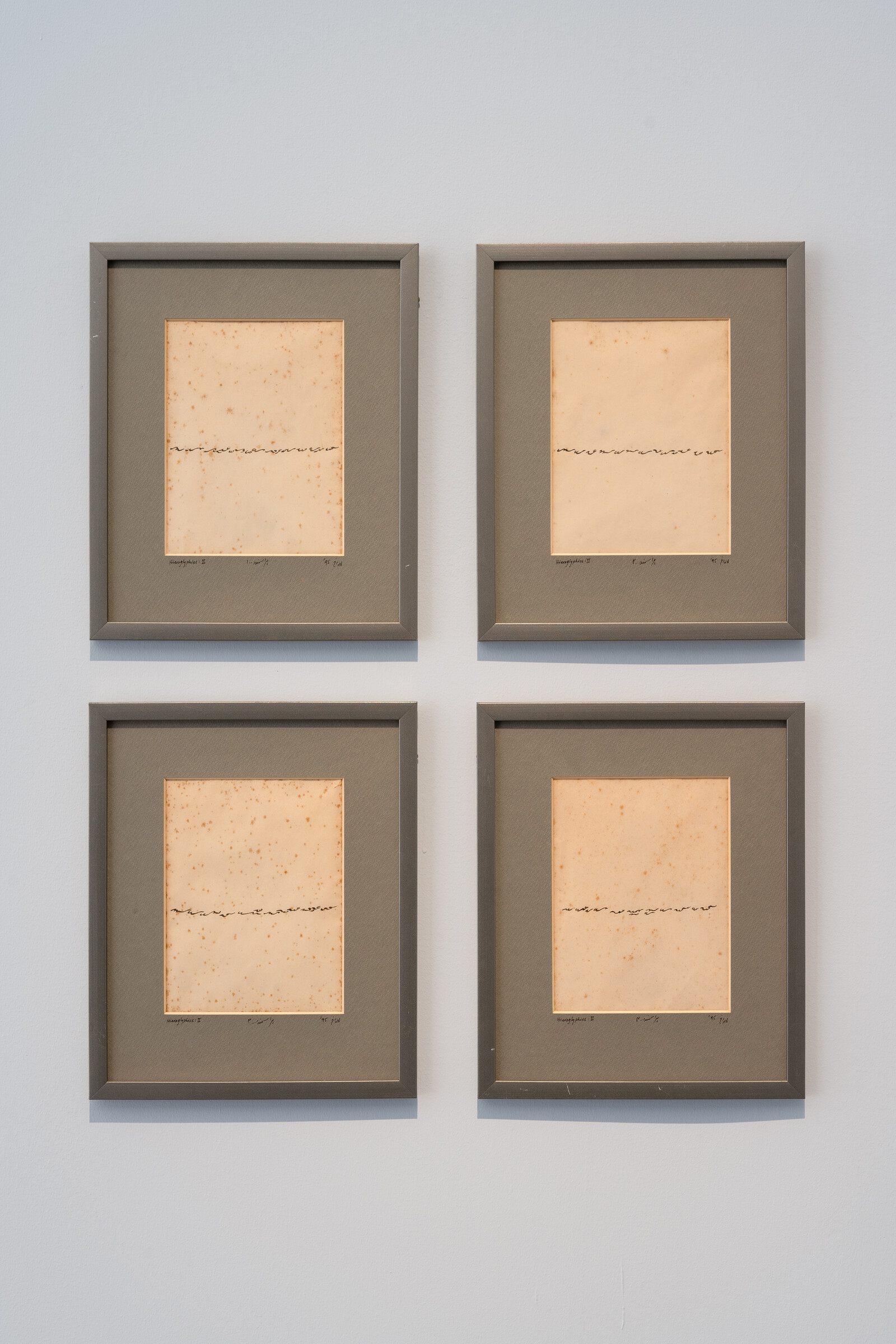

Perhaps because she was born and lived in landlocked Lahore, Lala was drawn to the ocean and its fluid poetics, its horizon of possibility, and its promise of connection with elsewhere. River in an Ocean: 5 (1993)—from a series of moody nocturnal seascapes inspired by a scene glimpsed out the window during a nighttime flight—is an early example of what would remain a lifelong fascination. Using delicate calligraphic marks in silver paint on murky exposed photographic paper, she creates a shimmering current of moonlight snaking through a dark watery expanse. Lala studied Urdu calligraphy with a master and it remained the basis of much of her mark-making. In the ink drawing Hieroglyphics I: Koi ashiq kisi mehbooba se (1) (1995) she turns Urdu’s fluid strokes into code, its subtitle referencing a famous poem by Faiz Ahmad Faiz. In the related Hieroglyphics II: Hara Samandar (1–4) (1995), by simply extending these marks to the sides of the page and dividing it horizontally, she transforms sentence into horizon, language into landscape, calligraphy into geography.

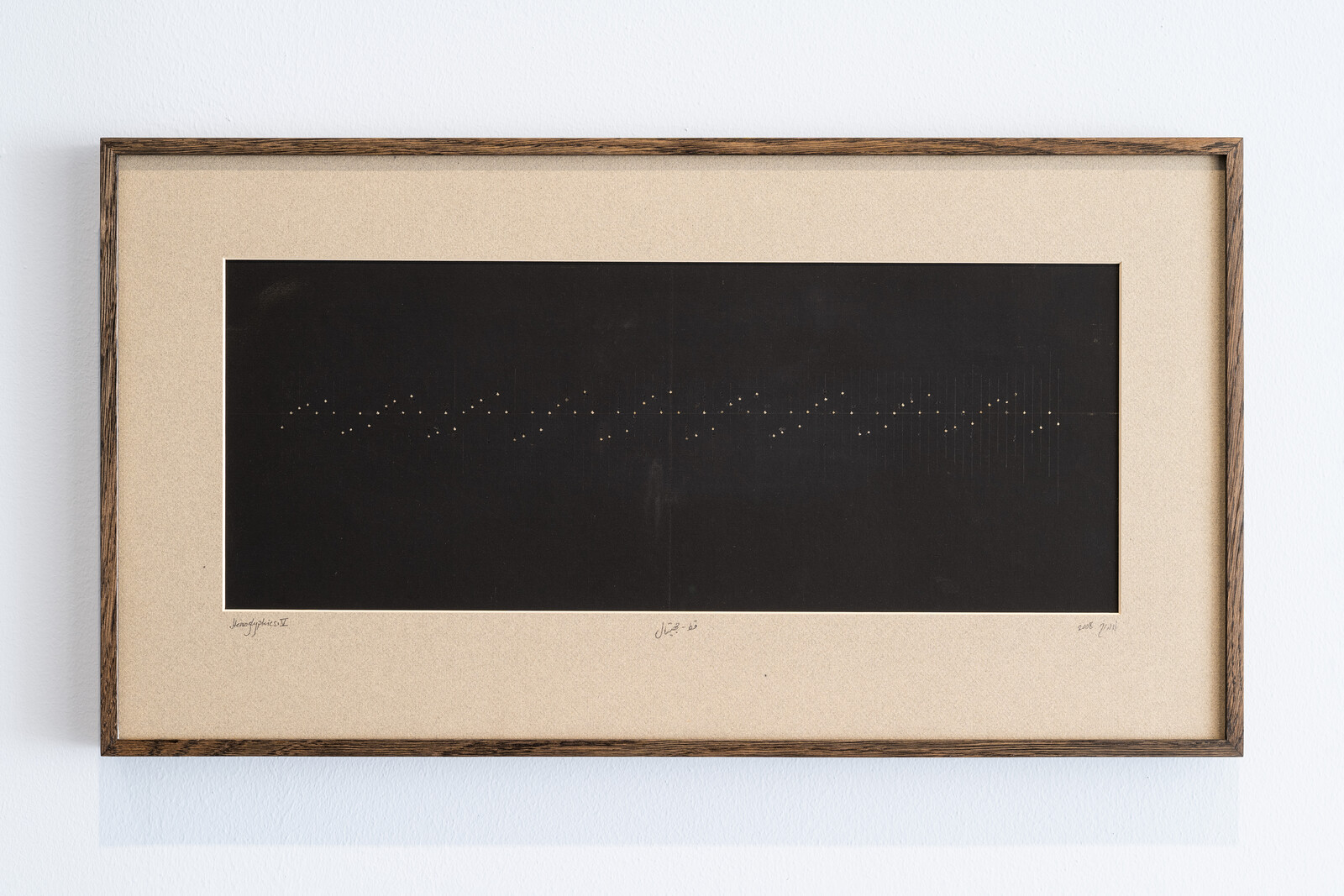

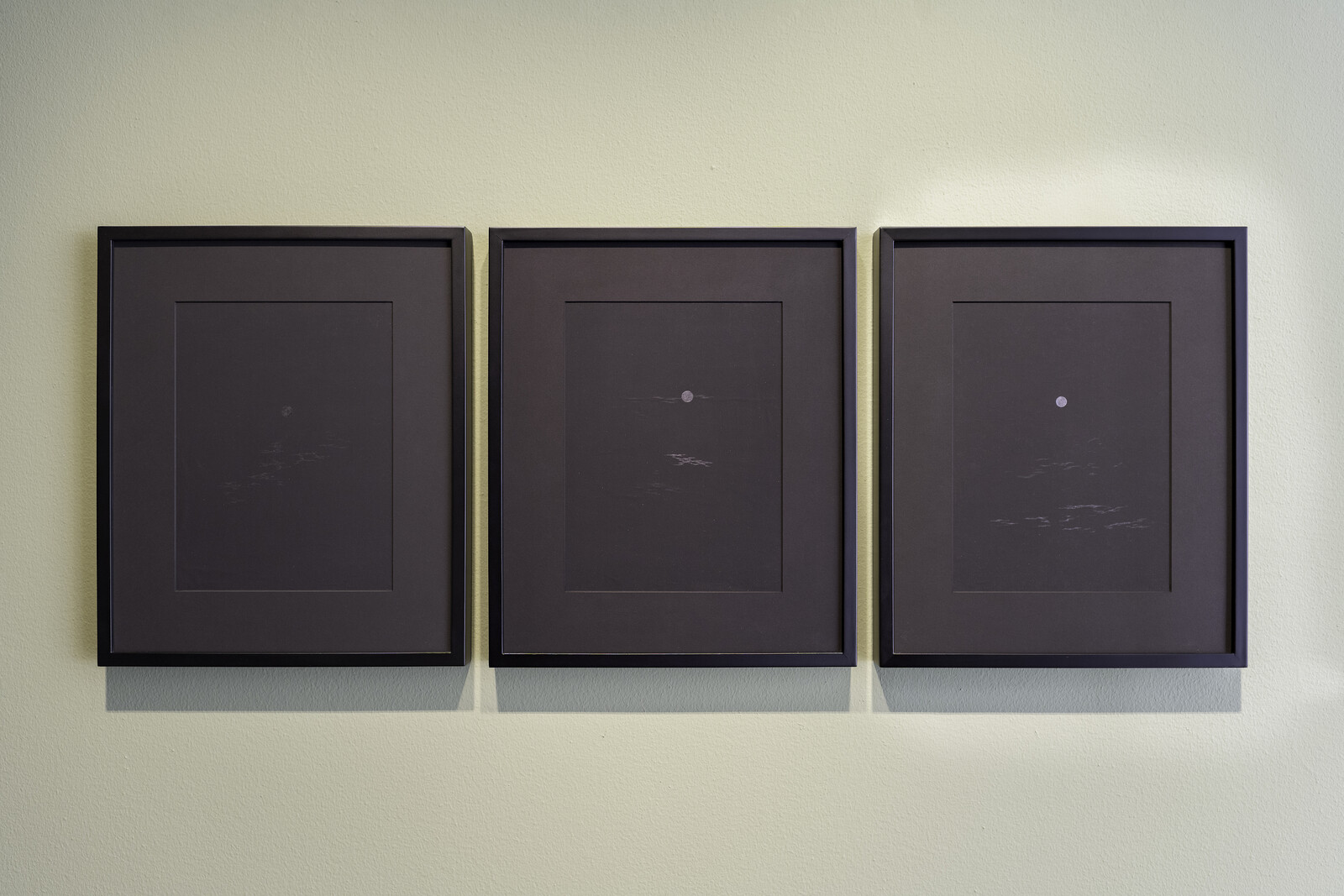

Hieroglyphics IV and V (2006–08) add music to this mix. Unlike its Western counterpart, Hindustani classical music does not have a standard notational system. It is instead taught and learnt using vocal and gestural cues (a clap of the hands or its intentional absence) imparted through embodied and intimate daily exchanges between master and apprentice. Lala adapted the qat—the rhomboid dot that is the basic unit of calligraphy—as a type of musical note to illustrate some basic rhythms and structures used in this musical tradition. Executed in silver paint on fragile carbon paper, the panoramic format of these drawings impels us also to read them as nightscapes, the repeating patterns of glittering dots resembling distant city lights seen from sea or a stream of passing ships viewed from a beach, recalling both Lala’s earlier work and what followed soon after. Pushing her minimalist convictions towards degree zero, in the triptych Moonscape 1, 2 ,3 (2010) Lala conjures up the titular scene with just a small circle and a few wispy lines in graphite. Against the sooty carbon paper support, graphite’s silvery sheen allows the marks to be visible when seen obliquely. In other drawings from this period, the line work is so delicate and spare that it is hard to see at all, leaving us to contemplate the deep quiet of black.

The exhibition concludes with Lala’s masterpiece Rupak (2016), a stop-motion animation based on the eponymous seven-beat raag played on tabla that was commissioned for Documenta 14 and completed the year before her passing. Building on Hieroglyphics IV and V, she divided the six-minute recording into equivalent sections each a few seconds long which she then meticulously notated as a series of drawings. These eighty-eight drawings, which are the basis for the animation, lean on a narrow ledge running along the curved perimeter of the darkened gallery, while the video plays within a diaphanous pavilion at its center, its percussive beats saturating the space around it. As the white qat repeatedly pings across the video’s black frame, variations in height capture shifts in tone and volume and quickfire polyrhythmic passages appear as rows or clusters. Music becomes the pulse of life, an antidote to the abstracted grief of Heartscape (1997), a deeply personal work that paired an electrocardiogram of the artist’s mother’s failing heart with a darkening progression of exposed photographic paper. Rupak is mesmerizing and meditative and, like the music that inspired it, is a mood and a reverie, like watching sunlight shimmering on the surface of water. It reveals a structure that is both progressive and recursive, repetitive but variable, much like waves crashing onshore. The series of subtly tinted photographs, prints, drawings, and a video of shorelines and water bodies, of sea foam in tidal pools and lines etched in coastal sands—shot by Lala over many years during conferences, workshops, and residencies across South Asia and beyond—that lead into Rupak seem to prime you for this revelation.

As much as this exhibition, through a sometimes-excessive reliance on the archive, tries to draw Lala into the light, she remains elusive. Paradoxically, she feels most present and alive in the reticence, restraint, and carefully cultivated opacities in and around her work and self: in the familiar-looking yet indecipherable codes, the beat (of life, love, loss, music, time, and nature) made image, the wistfully distant horizons, and the enveloping and comforting shadow of a near-total blackness. Such gestures towards “nothingness” are not voids, eliciting nihilistic or existential dread, but joyous plenitudes, brimming with productive solitude and infinite possibility.2 Like the oceanscapes that fascinated her, Lala remains distant, a horizon we strive towards but will never reach.

“Lala Rukh” was not the artist’s full name but her bipartite first name, which she preferred. For the sake of brevity and as a gesture of deference and affection, I have used the shortened form “Lala,” commonly used by her intimates.

Lala used this word to describe the endgame of her work of the early 2010s. Quoted in Jyoti Dhar, “Lala Rukh: Tranquility Amid Turmoil,” ArtAsiaPacific 102 (Mar/Apr 2017): 122–29.