September 6–October 6, 2024

Can belief bring things into being? There’s a theory that the word “Riga” derives from the ancient Livonian word “Ringa,” which implies a closed loop or ring—a shared reference to its circular harbor and the cyclical history that animates it. This explanation has been widely accepted, despite being disproven; it’s an urban myth which has—perhaps due to its lyrical charm—become a kind of truth. Many works in this year’s edition of Survival Kit, curated by Jussi Koitela, playfully straddle the line between fact and fiction, exploring degrees of constructed truths that hold special meaning to the city residents. Based in a former civic legislation building where bureaucrats once made decisions, and in a local hub across the river, the exhibition forms a bridge between Riga’s different hemispheres, timelines, and generations.

Survival Kit is a festival born out of necessity in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crash, when people began leaving Latvia to find work elsewhere, shrinking Riga’s population by about a third. Its mission was to animate the empty spaces left behind by people and industry, preserving local history and potentiality through the creation and layering of new meanings. Not all of them are here to stay. Linda Boļšakova’s installation of strawberry clover growing out of a massive pile of construction debris (Unearthed, 2024), for instance, might gesture at resilience, but the plants are destined to die, either of natural causes or when the installation is uprooted.1 On the facade of the main location, Rena Rädle and Vladan Jeremić’s aptly titled Zones of Truth (2024) are hand-drawn banners that illustrate the futile desires of local communities for locally informed social spaces instead of striving for some universal idea of a metropolis. Toril Johannessen’s aestheticized poster graphs Words and Years (2010–16) illustrate how the presentation of statistics helps construct their subjective “truth.”

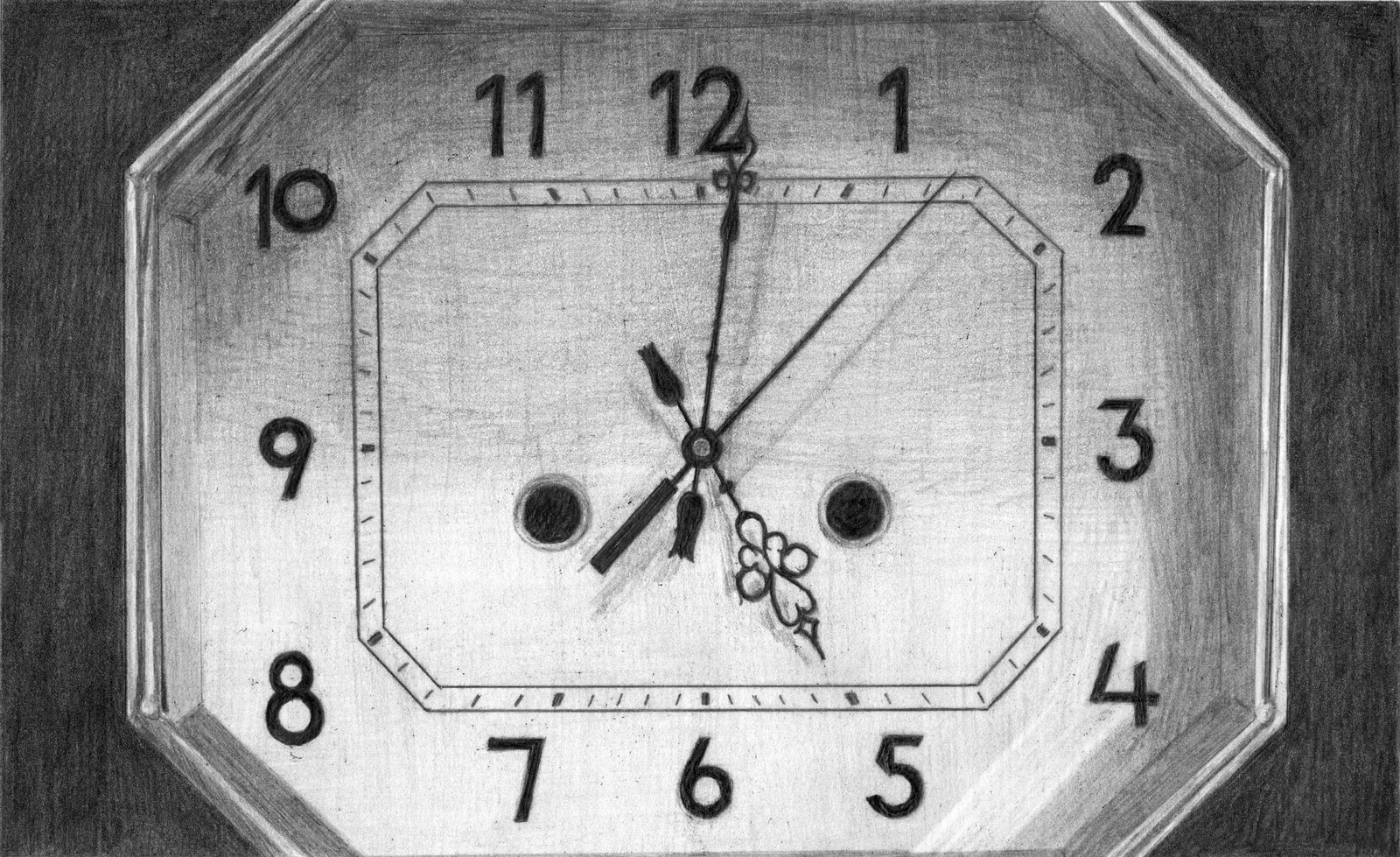

Plant or city, it’s hard to grow under unstable conditions. In nations which have had to rebuild after a prolonged occupation, history is marked by violent, sometimes unpredictable events which create distinct before-and-after moments. Multiple works here explore that feeling of temporal disjunction. Cartoonish pencil drawings of clock faces by Luīze Rukšāne (Clock, Clock, on the wall, tell me, what hour is suited for nothing?, 2022), are spread throughout the exhibition. Many pinpoint 5 a.m., the exact time that Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022. Eero Yli-Vakkuri’s frustrated, altered wristwatches (Our Greatest Times, 2024), decorated with nonsensical objects, seashells and rocks, point to hiccups and ambiguities in the linear timeline.

Traditionally, significant moments in time have been commemorated with monuments, but much of the work here challenges such confident displays of permanence. Kristoffer Ørum’s AI-generated anti-monumental scenarios (Monuments of a Fictional Past, 2024) imagine a Riga populated by bouncy castle-like contraptions that can easily be erected and taken down. They suggest that cities, like ideas and beliefs, are in constant flux, perpetually influenced by their pasts and present uncertainties. In the real Riga, a monument celebrating a Soviet soldier who supposedly liberated the city a century ago was recently dismantled. Despite public calls for a ceremonial removal, the city intentionally chose a random, unannounced date to eliminate the statue from its landscape. One day it stood, the next it was gone. Perhaps the authorities realized that the project of monumentality doesn’t always result in progress: the public takedown of the V. I. Lenin statue in 1991—a moment now celebrated annually by loyalists—has ironically immortalized the communist occupation in memory, rather than remove its traces.

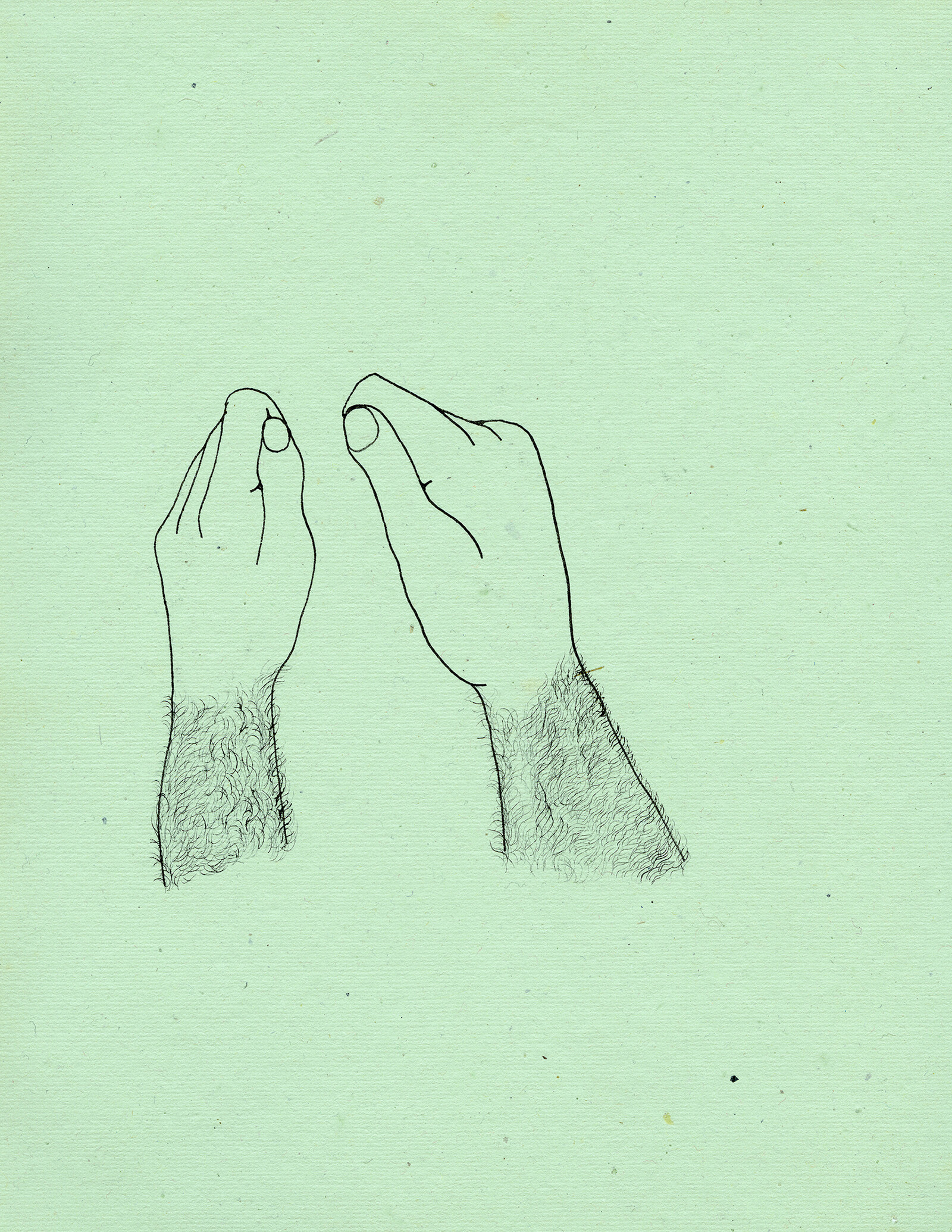

According to another local legend, once, to enter Riga, one had to bring stones that were later used to pave the streets in the old city. Whether true or not, this ritual resonated with the local community and inspired other hands-on city-building efforts. For example, during the 2014 construction of the new library on the left bank, thousands of citizens formed a human chain across the river to pass books from older buildings to the new library, hand-to-hand, each person imprinting a piece of themselves into the city’s fabric of knowledge—a history referenced in the intimate, durational performance video work of Malin Arnell and Mar Fjell (Please don’t end here, 2024), who traced the journey on a pair of handmade dollies.

Riga embodies resistance to change while being continually shaped by it. Projects addressing gentrification capture an unease with new construction, as people struggle to reconcile their bodily memory with a mutating cityscape. What’s going to happen here, next? Everyone has their own speculations. Līga Spunde’s re-presented work from her ongoing web project “Episodes About Not Knowing How It Will Be” (2024) portrays an image of a supposedly typical Latvian youth—nostalgic for the pastoral past, easily swayed by bombastic visions of the future, while wallowing in an internal world divorced from reality or reason. Yet it also presents a redeeming truth: sometimes, it’s best to admit you just don’t know.

Boļšakova plans to transplant the clover to a meadow after the exhibition ends.