Kim Lim’s dark wood sculpture Pegasus (1962) is an earthbound, stiff-backed version of the mythical flying horse. Shaped like a totem, it has no discernible head or legs, only a central column to which two slim semi-circular pieces of wood (the “wings”) are hinged. Pegasus, steed of the muses and symbol of the unbridled imagination, is portrayed here with a certain restraint. In fact, the sculpture reminds me of a practitioner of another disciplined art—a straight-backed ballerina moving between first and second positions, arms opening and closing gracefully.

Subtlety and economy define Kim Lim’s practice, which includes abstract wooden and stone-carved sculptures, often inspired by nature, as well as prints that were developed in tandem. Only in the past two decades has Lim received attention in her two home contexts: Singapore, where she was born in 1936, and England, where she attended art school, started a family, and lived until her death from cancer at the age of sixty-one. Major shows at Tate Britain and Hepworth Wakefield have situated her in British postwar art history alongside Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, and Lim’s husband William Turnbull. The Singapore Tyler Print Institute staged a retrospective of her prints in 2018, establishing her as a key emigré artist of the Lion City. Now, the National Gallery has given her a solo exhibition showing 150 works, offering a cogent and sensitive account of her career; according to publicity materials, the show seeks to “reposition Lim as a major figure in twentieth-century sculpture and printmaking.”

Split into four chapters, the show begins with an exposition of early works from Lim’s student days in the 1950s and ’60s at Saint Martin’s School of Art and the Slade in London: column-like formations mostly in wood. From this stage, her modesty and self-possession were already palpable in the coolly reduced forms. Samurai (1961), for example, comprises four pieces of wood stacked into a trapezoid form, with the squat base and round, chopping board “head” efficiently conjuring up the silhouette of an armored Japanese warrior.

The next section is the “fun” one, featuring her experiments with industrial materials like steel, aluminum and fiberglass, to create geometric forms in color. Here, a pure white sculpture catches the eye: Day (1966), a flat white arch that curves up and down in a tall, narrow vault—a luminous doorway. In the third section, we encounter her modular phase in the 1970s, during which she arranged wood and aluminum units into different patterns. Formally, the use of industrial materials and repetition makes this period the closest to Minimalism of Lim’s career, though her thinking is more organic, inspired by natural rhythms like heartbeats. Her serialization also has a figurative dimension, as seen in Irrawaddy (1979), named after the largest river in Myanmar. The work is made up of two rows of plywood blocks, partially stacked onto each other like a cascading chain, so that they flow from the wall to the floor.

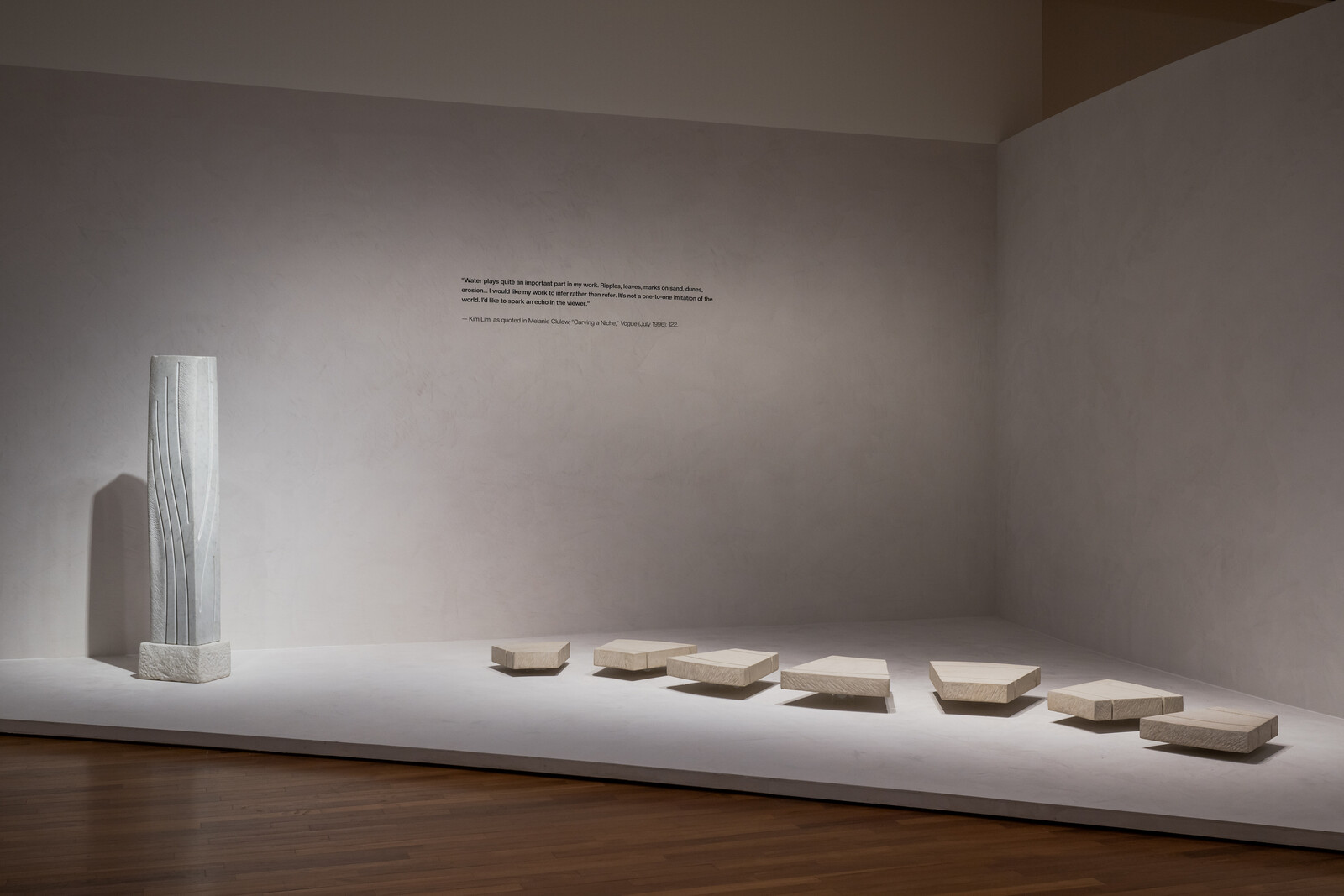

Then comes her late period in the 1980s and ’90s, my favorite, during which she ventured into carving in stone, and her strict mathematical permutations opened up to more sinuous, flowing lines. Her works distilled the forms and movements of leaves, flowers, bones, starfish, and shells. River-Run (1992–93) is a horizontal stone slab with seven lines of varying lengths carved across, with their subtle curves conveying the lines in a Japanese raked garden, or the drift of a current; the squarish stone relief Syncopation I (1995) comprises a series of diagonal slashes coming in from the edges that resemble the vein pattern of a leaf. In these works, Lim sought to evoke a sense of balance, which she described as “a symmetry that is experienced rather than actual.”

The conventional art historical narrative figures Lim as in conversation with both Eastern and Western traditions. In her undated typewritten notes, reproduced on the museum’s walls, you might find a sentence like “Visual reality doesn’t mean verisimilitude,” which has shades of Clive Bell’s definition of “significant form” in Art (1914) as something that strips away accidental conditions to let us “become aware of… essential reality, of the God in everything, of the universal in the particular, of the all-pervading rhythm.”1 Here, the exhibition takes greater pains to establish her Asian influences. On show are a sizable archive of Lim’s travel pictures, including Buddha faces made from stacked pieces of rock in Angkor Wat and roofbeams of temples in Nara, Japan, which correspond with her compositions. With these references, the curators posit that she had a multicultural worldview that was richer than the narrow confines of European Modernism.

This is an important conversation to initiate, and it is hard to disagree with this line of thinking. But ultimately, the most valuable thing that “The Space Between” provides is not a scholarly framework, but a direct encounter with her work. By her own account, Lim’s abstraction relies on “material that came from the seen and felt world,” yet magically confuses and confirms our habitual perceptions of it. A memorable work from her late period is Padma III (1985), named after the Sanskrit word for lotus, which at first glance, resembles a sturdy stone boundary marker rather than a delicate flower. But closer inspection reveals its subtle design. Vertical lines carved into stone separate the sculpture into four segments. Appearing closely pressed to each other, every segment is gently bulging in the middle as if growing fat. Despite the work’s stout, bulky form, it still evokes the process of creamy, slow expansion—like lotus petals opening up to the sun.

Clive Bell, Art (New York: Capricorn Books, 1958), 54.