As a kid growing up in Berkeley, I oriented myself by the silhouette of Mount Tamalpais, crisscrossed its slopes on foot in every season, even touched fingers to a rare flocking of snow at its peak. That an artist living 5,500 miles away might pay homage to this local landmark without ever having seen it in person—as the London-based painter Caragh Thuring has done—was a compellingly fantastical proposition.

My mind, of course, went to Etel Adnan, whose vivid, Platonic paintings of the mountain are among her most iconic. From the time the Lebanese-American artist and writer moved to Sausalito in the late 1970s—where it was in plain and constant view—and well after her move to Paris in later years, Adnan painted hundreds of views of Mount Tamalpais, which she described as “the very center of my being.”1 You cannot look at Thuring’s string of small canvases (smaller than she has worked on for years), and not think of Adnan’s intimate, lapidary portraits of the same landmark.

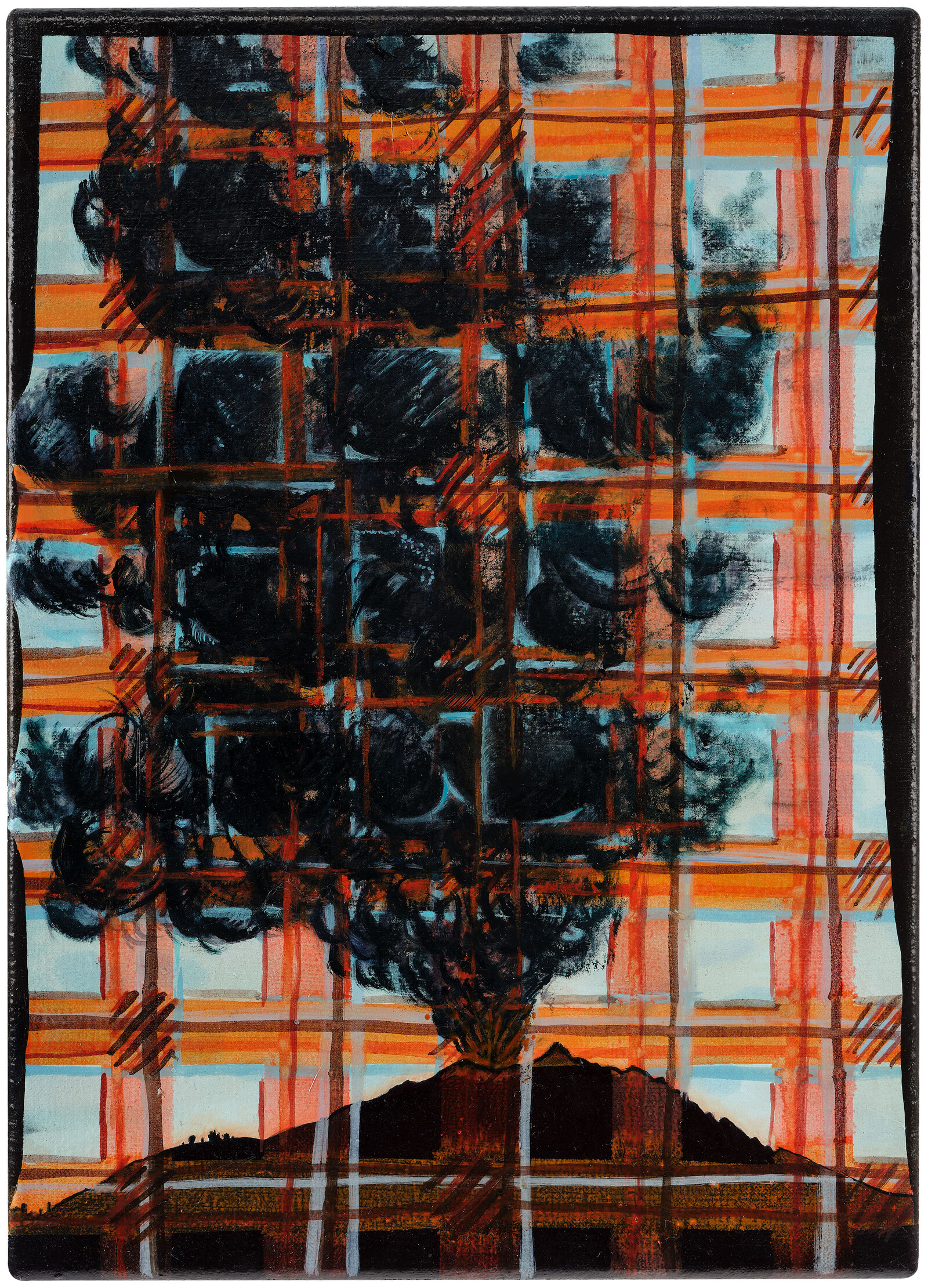

Yet Thuring swiftly and assertively makes the subject her own. The painting opening the exhibition, Given Enough Goading (all works 2024), transforms Mount Tamalpais into one of the artist’s recurring subjects: a volcano, replete with a scrubby, billowing plume of black smoke. A tartan plaid—another of Thuring’s trademarks—overlays the whole of the painting. As a type of pattern, tartan is inherently territorial—in deploying it, Thuring makes a claim on the subject. The show will unfold according to her own rubric.

Over the course of its relationship to human beings, the mountain has been—and been imagined to be—many things, one of them a volcano. Its uneven apex, long sloping flanks, and crater-ish mien, gave rise to the enduring misperception. Thuring seized upon it, crafting a narrative around a favorite subject, an old familiar. What emerges from her preparatory perambulations through internet searches, archival material, vintage postcards on eBay, maps, and photographs is a disarming series of paintings that read a bit like abstract translations of the source material. These are transmissions from across time and space, queered by technology, distorted by the turning over of centuries, and infused with Thuring’s irrepressible imagination and aesthetic panache. The result is beguiling: like receiving a flurry of cartes de visite in the post from a cousin on the Grand Tour who’s just glimpsed Vesuvius in full bloom.

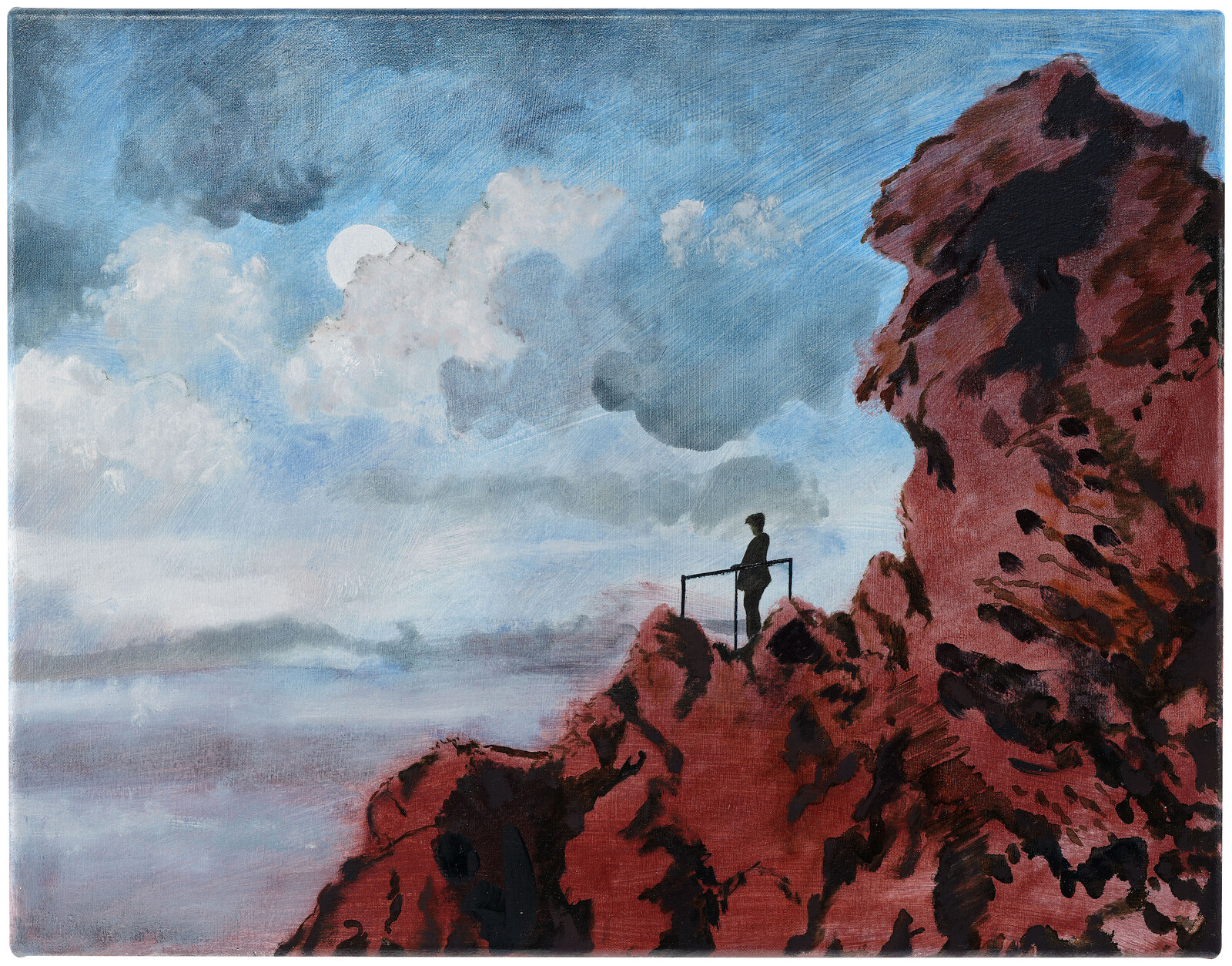

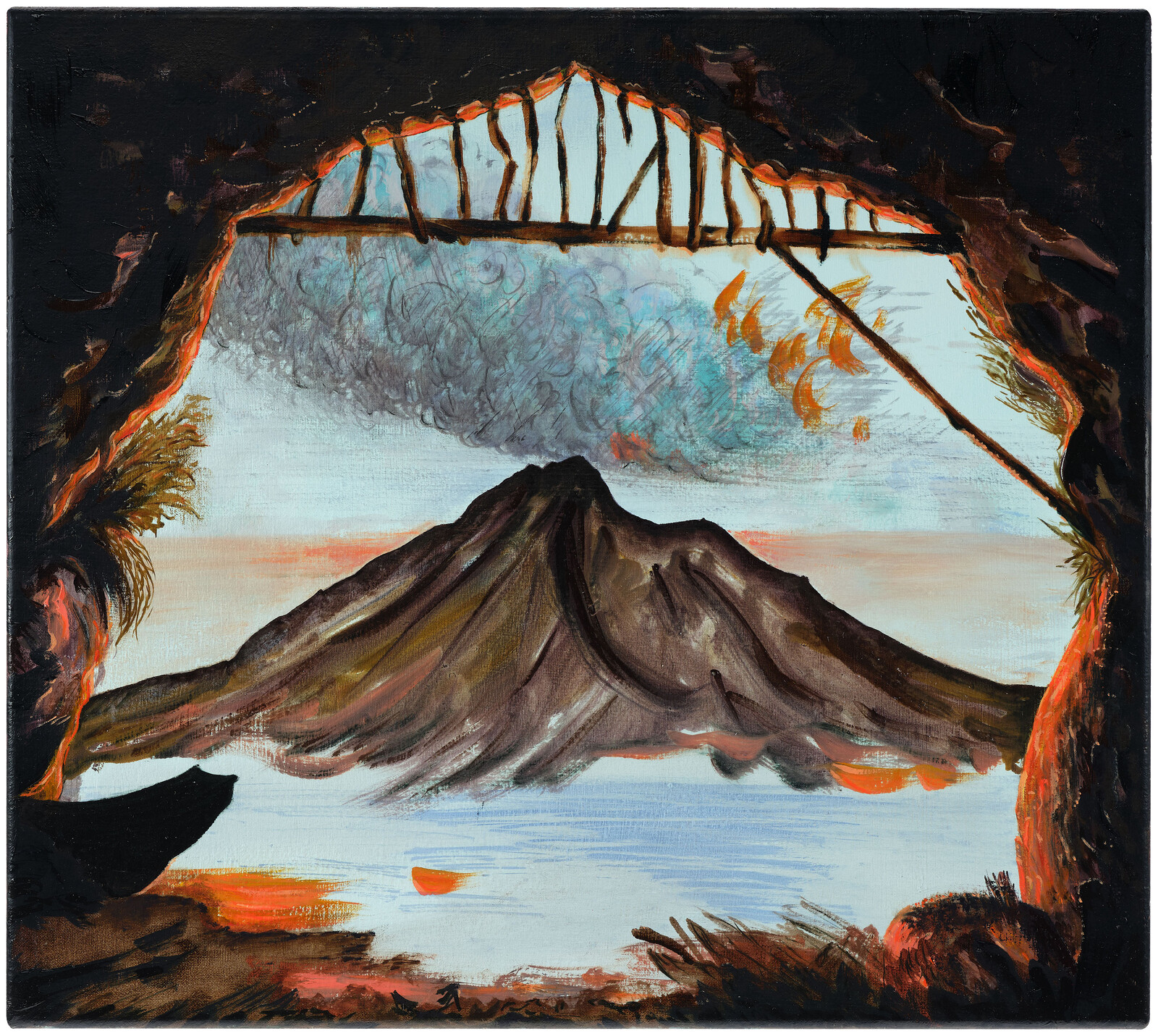

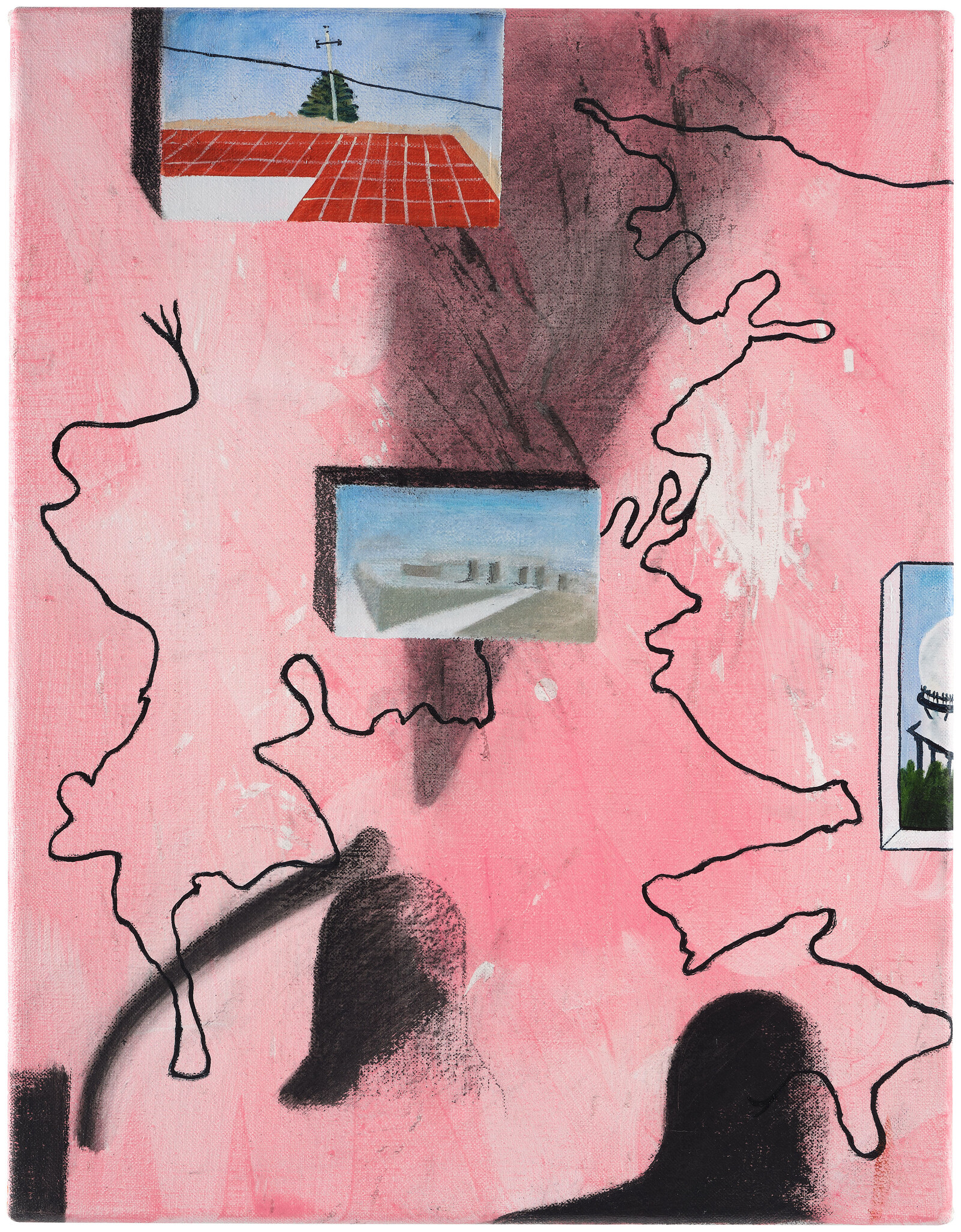

Thuring plays this up, describing one painting, Volcanic Slippage, as “Italianate picturesque,” though the mountain, viewed from within the mouth of a cave limned in a fiery red not unlike the “International Orange” of the nearby Golden Gate Bridge, is entirely more ominous than that phrase might suggest. Thuring found herself fascinated by the scars the mountain bore: of a Cold War radar missile station, a defunct nineteenth-century railway, devastating fires, industrial radio towers, endless human exploration, recreation, and exploitation. A particularly lyrical canvas, Debris of the Grind—painted in a soft, nail polish pink—bears the cicatricial remnants of what was nicknamed the “Crookedest Railroad in the World” in a map-like view from overhead. Smaller images depicting scenes from the disused Cold War-era radar site hover overtop, akin to open browser windows on a desktop screen—a painting as palimpsest, collapsing 1896, 1951, and now. And while the human mediation that so captivated her is everywhere in these works, it is given literal form in two canvases—It is Faulting and Some Men each portray a kind of Rückenfigur in obscured silhouette, one gazing into a pale blue miasma from a craggy promontory, and his sepia-toned twin, a lone John Muir-ish figure surveying a distant peak. Facsimiles of David Friedrich’s famous wanderer—transported to a new world of giant redwoods and violent fault lines—though the sea of fog features elsewhere. You’ll find it, cartoonishly bulbous, marshmallowy, sidling up to a verdant slope in Blanket.

The exhibition toys, in a way that is entirely consistent with Thuring’s practice, with indexicality—she mines not just images from the internet, but images from her own work, her photographs from other contexts, her memories. She strikes a delicate balance between sincerity and caprice. There is nothing sarcastic, nor mocking, about these works, though they freely undermine the genre of “landscape painting.” I think of Ed Ruscha’s 2005 “Course of Empire” series—inspired by the nineteenth-century landscape painter Thomas Cole—in which he reprised subjects from works he’d made nearly two decades earlier. A wry investigation of the march of human “progress” rendered in Ruscha’s signature palette—bleary, sometimes lurid, exhausted-looking skies—finds an echo in Thuring’s body of work. There is, however, more pleasure here, more sensuousness, more beauty, more imagination, more humor—even in the face of ancient travesties. Mt. Tam, it is clear, has become an old friend.

Etel Adnan, Journey to Mount Tamalpais (Sausalito: The Post-Apollo Press, 1986), 10.