“I’ve always been obsessed with losing my memory because it’s something that runs in my family,”1 Mohamad Abdouni remarked last year. Long a driving force of his practice, photography has allowed him to excavate, reinvent, and remember queer histories in Arab cultures. Here Abdouni shifts view to his home region of Beqaa, Lebanon. In pulling apart family photo albums, subjecting them to the scrutiny of his loving but unsentimental gaze, the artist returns to his childhood navigations within the complex cultural norms of a heterosexual masculinity and male camaraderie that embody Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s theory of “male homosocial desire” grounded in anti-queerness.

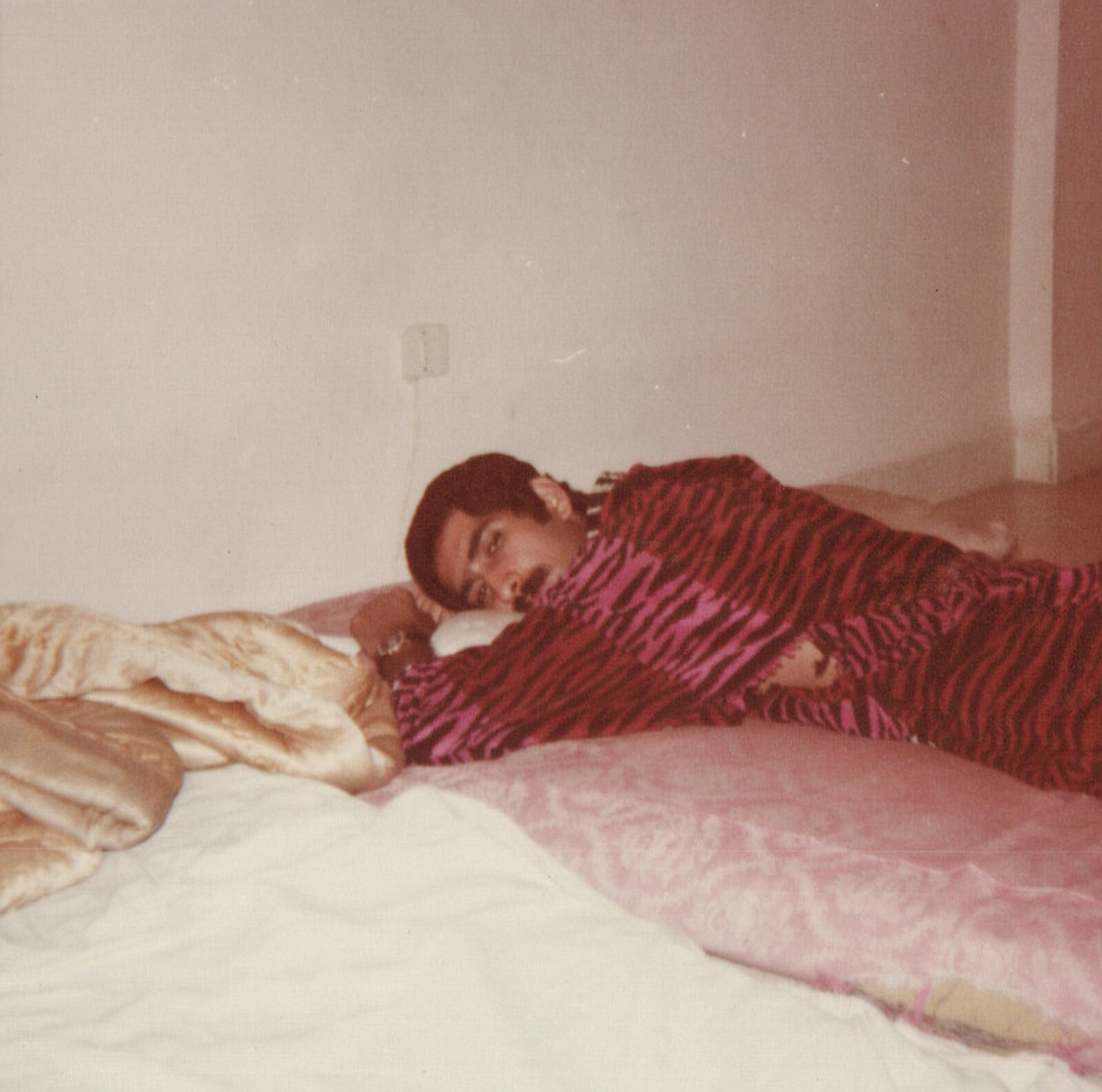

The exhibition’s title refers to other types of skills soldiers might be required to demonstrate outside mastery of arms. In Abdouni’s hands, time-worn family images become soft evidence, pointing to the ways in which a child’s queerness resisted masculine norms and strained interfamilial relationships. A father gazes, disapprovingly perhaps, towards a little boy posing cross-legged in a green plastic chair (How to Properly Sit on a Chair, 1996). “Straighten your screws,” Abdouni was told as a child. Act like a man. Yet, the deliberate selection of images here—mostly of men, mainly Abdouni’s father—disrupt stereotypes of Middle Eastern men for more imaginative rereadings of normative masculinity. An intimate portrait of Abdouni’s father in bed, lying on pastel pink sheets wearing silky zebra pajamas, staring directly at the photographer (My Father in Zebra, 1977/2024) is juxtaposed against a tiny polaroid of him being shaved (My Father Shaving for the Military, 1984/2024). Taken seven years apart, the thoughtful placement of these images speaks to the ways in which men regularly enact masculinity in multiple, sometimes culturally conflicting modes, as they move through the different contexts and communities that shape their lives.

To the extent that “Soft Skills” reckons with irreconcilable conceptions of masculinity, archetypal women also loom large. Near the entrance hangs a mesmerizing photographic collage of a scrubby, mountainous landscape overlaid with a black-and-white archival image of a veiled woman facing a lake, her arms outstretched wide (The Bedouin Witch of the Quaroun Lake, undated, on Untitled, 2024). Abdouni increasingly uses AI to fabricate images of queer Arab histories where lacunae exist and this AI-generated “archival photo” depicts a Bedouin witch, a frequent character in Beqaa tales. In a culture where traditional family structures remain important, for Abdouni the witch is relatable. One of many monstrous women disdained by society, her strength and freedom are worthy of celebration.

Another strong woman, Abdouni’s grandmother, is a constant presence. During the Lebanese Civil War, some of Abdouni’s extended family fled the country. Unable to read or write, his grandmother recorded long messages to her children on cassette tapes.“Bismillah al-Rahman al-Rahim,” her voice echoes throughout the room (Letter from Aisha, 1977). She speaks of the family’s concerns for a particular uncle, the desperate need to find him a wife. Her long letter, dictated in 1977, with news of shelling in Sultan Yacoub, is also a pointed bridge between past and present at a time when Israel’s catastrophic bombardment of Gaza has expanded to Lebanon. Beqaa has been subjected to war and invasion many times in its history, most notably in the 2006 war with Israel; masculinity there, as elsewhere in the region, remains deeply tied to warfare, resistance, and martyrdom.

Across the room, a plinth holds a vignette of two aluminum figurines, painted to mimic glazed porcelain, positioned among rocks and branches (Village Scene (Cruising), 2024). Drawing on memories of his grandmother’s precious porcelain, which Abdouni later realized were not priceless family heirlooms but mass-produced western trinkets, a neoclassical scene—inspired by eighteenth-century depictions of satyr seduction—has been reimagined as a pastoral cruising encounter. An elegant sweep of drapery gives a coquettish air to the male figure playing the nymph’s role in the foreground. Behind the branches and rocks, the second figure has all the erotic humor of a satyr, but the overall effect is less violent than many neoclassical counterparts, softened instead by the implied consent and a subversion of the “boorish” stereotype.

“Soft Skills” shows the power of Abdouni’s joyful and playful meddling in normative conceptions of masculinity. Softness abounds. In the folds of cotton pants, in the draped wrap of a cruising nymph, in the grain of old photographs that speak to a family’s love; in the making visible of queerness that was always already there, a puncturing of what Lebanese writer Mai Ghoussoub has described as “men’s tortured conception of their own ‘masculinity’.”2

Ella Martin-Gachot, “At Paris+, a Lebanese Artist Asks AI to Produce an Archive of Histories That Were Never Recorded” Cultured, October 18, 2023, https://www.culturedmag.com/article/2023/10/18/paris-mohamad-abdouni-artist.

Mai Ghoussoub, “Chewing Gum, Insatiable Women and Foreign Enemies: Male Fears and the Arab Media,” in Imagined Masculinities: Male Identity and Culture in the Modern Middle East (London: Saqi Books, 2000), 230.