Heidi Bucher’s Skin Room (Rick’s Nursery, Lindgut Winterthur) (1987) is a mold made from latex and fish glue of a friend of the artist’s childhood room. On view at the Migros Museum as part of a collection show titled “Material Manipulations,” this “skin” hangs by clear strings from the ceiling: yellowish, haunting, still recognizably domestic. Next to Bucher’s sculpture, in Martín Soto Climént’s The Swan Swoons in the Still of the Swirl (Stills 1,2,3,4,5,6) (2010), metal Venetian blinds hang, spread like handheld fans, from ceiling to floor. These elegant sculptures, like Bucher’s work, figure the home as physical artifice, bricks and mortar, more material construction than abstract idea.

The effect is alienating and evocative at once, and the fragility of these homes suggests the impossibility of conceiving of the home as simple refuge. A second show at the Migros, Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape’s “(ka) pheko ye – the dream to come,” subverts this construction of home by bringing to the museum the very real conditions of Bopape’s native South Africa through clay display structures that echo the front yards in which people congregate, work, and socialize. Bopape makes a place for dreaming and “collective healing” through both objects—like the projector set on a scattering of star anise pods, creating a starry night on the wall—and affect, like the scent that permeates the exhibition, earthy and herbal, meant to evoke that of South Africa after the rain.

Sometimes it’s hard to look at objects without imagining them as remnants from a world bound to disappear. In a corner of Ana Jotta’s exhibition at Kunsthalle Zürich, a pair of bronze-cast shoes, Je dors, je travaille (2019/23), give the impression of having been forgotten by their wearer. Jotta, a Portuguese artist who rose to prominence in the 1980s, attempts to rehabilitate found objects’ relationship to the world rather than produce new ones. “Dietrich” at Francesca Pia includes the work of seventeen women artists offering different representations of object history, in which the works suggest older or fictional material cultures: Beverly Buchanan’s three iron sculptures (Untitled, ca.1971–88) look like they belong to an ancient civilization; Isabelle Cornaro’s Composition (2024) places objects including a chain, jewelry, and rocks in a vitrine, making them seem like loot; and Olga Balema’s polycarbonate sculpture Loop 56210 (2023) resembles industrial scraps re-treated to belong in the gallery.

“Ahoi, ahoi Des Admirals,” at Barbara Seiler is dedicated to performance (and takes its title from a Dada performance at Cabaret Voltaire in 1916). Sophie Jung’s To snare a sensibility in words (2023) combines a motorized baby bouncer missing its fabric seat, a found textile piece showing a man knocking on a woman’s door, and a metal rod that pierces it. During Art Week, Jung performed regularly as part of this work, reading a wild text tying together the absence of the baby and the looming encounter between the characters depicted in the textile. Dina Danish’s You’ve crossed the line! (2014) is printed on the gallery’s entrance, meaning that to walk in is to enact the artwork. Shana Lutker’s To Die (2024) is a printed-out script about dying which the viewer is invited to read.

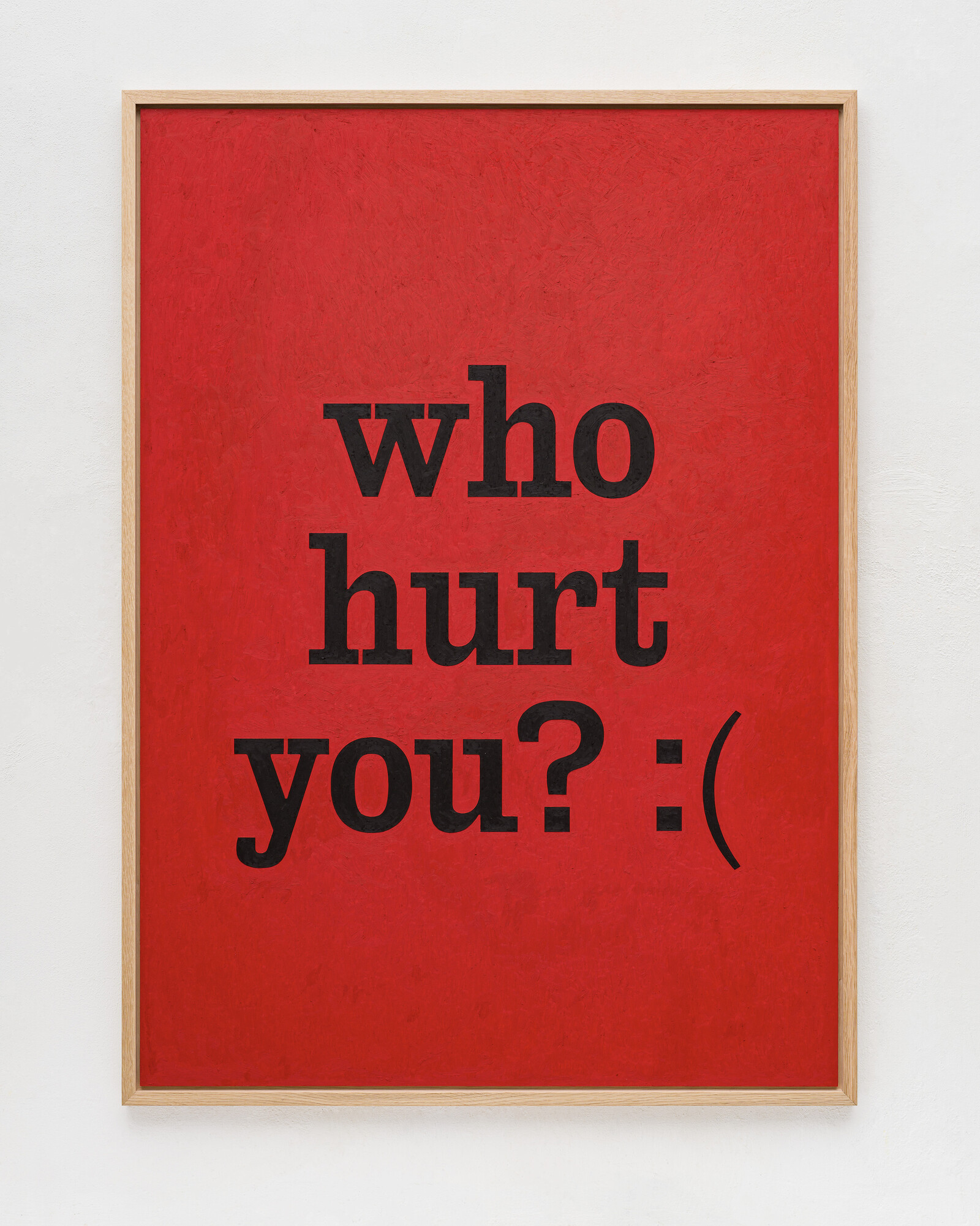

Nora Turato, in her show at Gregor Staiger gallery, similarly involves the viewer. Or maybe she doesn’t? I couldn’t be sure. Upstairs, there are text works in oil pastel on paper, reading lines like who hurt you? :( and door knob, TURN!! (both 2024). In the dark, musty basement is a sound work. As I approach it, I hear heavy breaths and hesitate. A woman’s voice says: “Hey, hey, come here. You’re such a good girl.” I must have come at the beginning of the loop, because the voice continues—“Hey, it’s ok. We are not crying. You’re safe now”—but as it sends chills down my spine, and I start walking away, it says, “don’t go.” The age of the amateur (2024) is one of the most effective site-specific works I’ve ever encountered. But it was so haunting and intense that I did, indeed, go.

Even more foreboding: at Kunsthaus Zürich, “A Future for the Past” explores the collection of Emil G. Bührle, which entered the Kunsthaus on long-term loan in 2021. Bührle made his fortune manufacturing arms for the Wehrmacht, and many of the works in the collection were acquired in more or less coercive ways from Nazi victims. These Renoirs, Cézannes, and Monets are lovely; they’re also tainted. It is important to reflect publicly on the relationship of institutions to the historical conditions that created their collections—“Entangled Pasts” at the Royal Academy in London earlier this year took the same line on slavery and colonialism—even if the results often end up feeling insufficient. As the Bührle Collection settles into its new home at the Kunsthaus, the examination of these artworks’ initial displacement reframes them as objects haunted by their histories.1

That said, it is possible to make a new home for art. When photographer David Armstrong passed away aged sixty in 2014, he asked Wade Guyton to care for the tens of thousands of photographs, mainly portraits of friends and associates from Nan Goldin (Armstrong’s classmate in art school) to Gary Indiana, that he left behind. There’s documentation of a social scene in New York in the 1970s and ’80s: days out at the beach, parties at the Mudd Club. The portraits are tender, warm, attentive. Guyton assembled a team of people to go through Armstrong’s archive, assuming it would take them a few months to organize. Instead, they’ve been working on it for a decade: indexing, identifying the individuals in the photos, matching contact sheets and prints. The show at Kunsthalle Zürich is the first extensive exhibition of Armstrong’s work and it’s a revelation. The attention to other people Armstrong’s photographs extend is matched by the work done to frame and conserve what he left behind. Remnants are not only haunting, ghostly things: they can be reminders of who we were, how we made the places and people around us, how we built our lives.

On 14 June 2024, Kunsthaus Zürich issued an update to the effect that it had been “informed by the E. G. Bührle Collection Foundation that it is seeking solutions with the legal successors of the former owners for six works in the collection” after the board reassessed the provenance of the works. As a consequence, five of the paintings were removed by the Bührle Foundation on 20 June.