“I would like to talk about my practice from the body of a dirty, envious dog that roars and emits secretions,” wrote the Ukrainian artist Katya Libkind in late 2023.1 Working in media as varied as set design, installation, and video, Libkind has described her work as “based on proceduralism, radical sincerity, and direct emotional experience.”2 With a focus on environment, community, and care, she explores ideas of beauty, doubt, and intuition in life and in dreams. In addition to working with atelienormalno, a workshop studio for artists with and without Down’s syndrome, she has taught art in a psychiatric hospital, and all of these experiences play into her multidisciplinary practice. Why did Libkind use the image of a dog when discussing her work?

Images of dogs in desperate straits have served as metaphor for the Ukrainian artistic community—conjuring a sense of confusion and the desire to cling to others to survive. I remember the abandoned street dog in photographs by Kharkiv artist Jury Rupin in the 1970s, personifying the aloofness, indifference, and loneliness of the Ukrainian intelligentsia during Soviet times.3 Two more recent iconic images: the dog who refused to cower on the ground after hearing explosions in Irpin in spring 2022, and another photographed by Serhii Korovayny in Kherson in summer 2023, grabbing a person’s legs with her paws and trying to hide.4 These dogs are not abandoned but paralyzed by violence. Libkind’s metaphor evokes another vivid state—the desire to abject her body in a time of war.

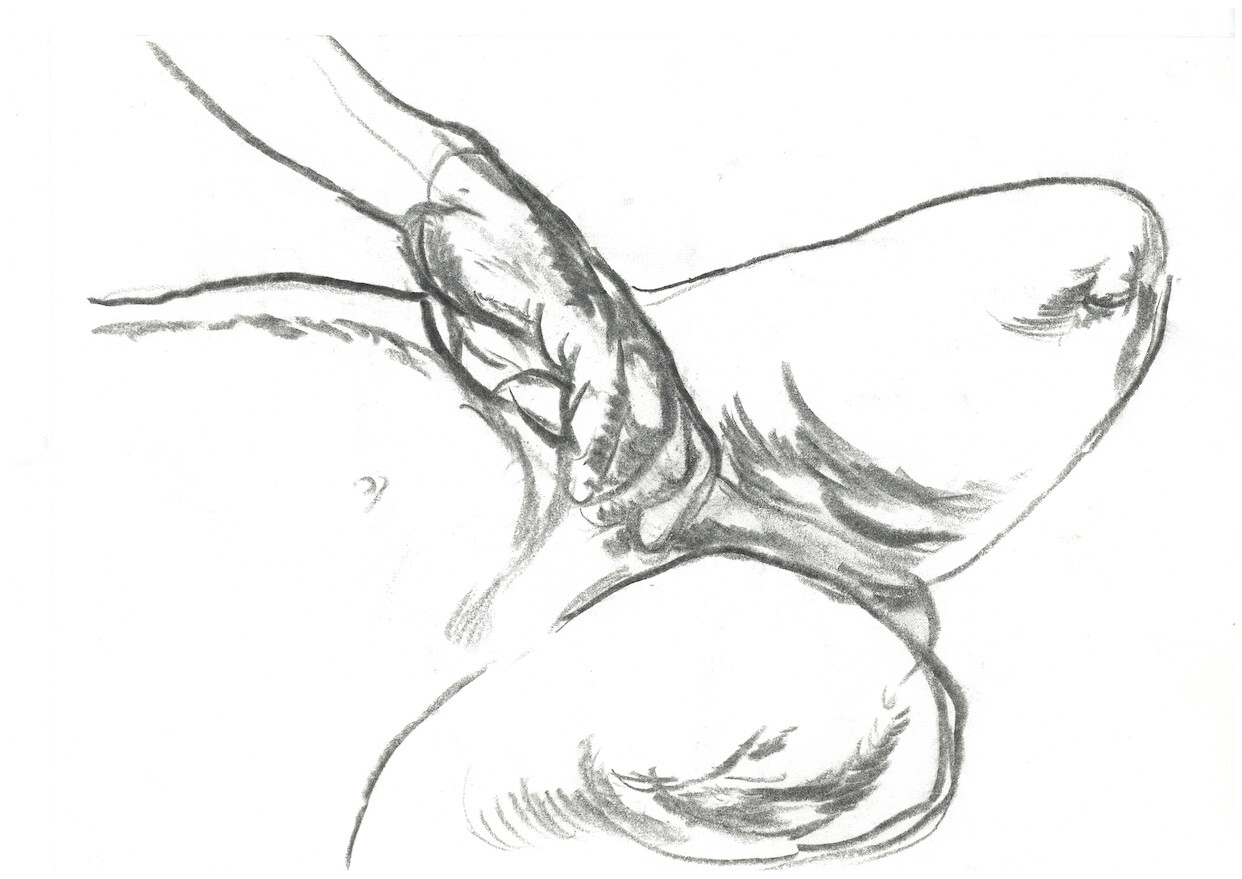

Katya Libkind, From the Sleeping during curfew, 2024. Pencil on paper, 21 × 29.7 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

Libkind’s home is located near the so-called defense line of Kyiv, on the western outskirts. When war came, she didn’t want to feel fear in the eyes of death and so went outside her house and lay down on the ground, like the dog on the road in Irpin. It seemed to her that the fear that possessed her body would pass into the ground, like the rainwater that sprinkles the soil. She lay, imagining her body already dead and therefore not vulnerable to murder. After all, the body cannot be killed twice.

“What disgusts me the most is that now I hate myself as much as I did in January,” wrote Libkind in her diary in April 2022. “I decided that now my self-hatred would be radical, but it would be just as miserable. Now this room will bore me.” In summer 2024, at the invitation of a literary residency in Gdańsk, she created an installation, A Heavy Declaration, to convey this sense of disgust. She made a flag from her belongings and rags, which she had previously covered in fat and black soil, and wrote on it “One hundred years” (a traditional wish for a long life). This flag looks like it was pulled from the grave—it reeks of death. But residents of occupied cities buried Ukrainian flags in the same way in 2022, just as Crimean Tatars, later deported from their native peninsula, used to bury their own documents and artifacts.

At her solo exhibition “I Wish It Hadn’t Happened” at artist-run gallery thesteinstudio in summer 2024, Libkind exhibited socks and underwear, collapsed in the ground, as if they were rotting. This dirty physicality is about trying to shed one’s skin: to be exposed to the circumstances of war and violence, and perhaps to bury personal vulnerability by bringing out one’s natural rage. Here, this anger was not directed towards the enemy but primarily towards the artist herself: misery before the death that surrounded her, and frustration about her inability to influence the situation. The exhibition showed the full range of Libkind’s work—graphics, paintings, moving images, scenery, texts, records of dreams about art and human relationships, a laptop displaying archival projects, a fountain of blood, earrings decorated with pubic hair, and the remains of soil on thin panties drying on a clean gallery battery. The earth on these private things is a legacy of war that will remain forever. This extreme materiality of loss and the need for protection suffused the fabric of the delicate clothing, creating an earth-body sculpture as a powerful anti-war image. This is the body of the artist. Her blood, her bones, her entrails. Look, smell, drink. Wake up to the beastly smell of blood and sweat. There won’t be another year like this, there won’t be another art like this.

View of Katya Libkind’s “I Wish It Hadn’t Happened” at thesteinstudio, Kyiv, 2024. Courtesy of the artist and thesteinstudio.

This body can make you dizzy from its stench. It is discomfiting to be witness to someone else’s underwear and hidden thoughts, their sexual act, splashed with venom, urine, and saliva. But in this respect it reflects the experience of Russia’s full-scale war—it exposes the dirtiest, most vulnerable sensations and pours them out. This is not the artist exposing herself to the viewer—the war exposes and deprives a person of privacy.

I think of Ana Mendieta’s 1981 poem “Pain of Cuba”, in which she describes being “covered by the earth whose prisoner I am / I feel death palpitating underneath / the earth.” Mendieta goes on to assert that she will go on making art, despite the death all around her: “to go on is victory.” I am struck by her metaphor of being imprisoned in her land—is that a personal choice, or an artist’s choice, or a choice that her art makes for her? What does this metaphor mean in the context of today’s Ukraine?

Not being able to go abroad because the need disappears, not being able to think about yourself or others (under certain circumstances), not being able to sleep (because of explosions, but primarily because of talking to yourself), not being able to have sex with those for whom you feel an uncontrollable desire. In one, untitled series, Libkind depicted sex amongst people who have lost limbs. She asks how an injured body, in permanent pain, might derive pleasure. Restraint is required only in things that pertain to life; in death, no one restrains themselves. The fountain of Libkind’s blood was eventually removed from the exhibition because of its overpowering smell. Did death conquer life?

View of Katya Libkind’s “I Wish It Hadn’t Happened” at thesteinstudio, Kyiv, 2024. Courtesy of the artist and thesteinstudio.

Mendieta moved to New York, but her body and life forever belonged to Cuba. Libkind continues to live in Kyiv; her body is imprisoned in this space, among the forests in the northwest of the Kyiv suburbs. In “I Wish It Hadn’t Happened,” Libkind has created a total installation in which everything seems excessive and corporeal; it surrounds you, fills you up, and interferes in your personal space. It’s her first exhibition, and—given the uncertainties engendered by the ongoing war—possibly her last. It is about presence, not only in a specific time but also in the history of Ukrainian art: an exchange and collaboration with others, an attempt to reclaim her body through these art objects and living archives. An attempt to break out of the war.

What is disgusting about Katya Libkind’s work? What causes such a feeling of awkwardness, discomfort, and rejection? In the show, every wound depicted invokes the potential death of the artist herself. Julia Kristeva writes that a dead body is abject—wretched, miserable, insignificant: “It is death infecting life.”5 According to Kristeva, an encounter with a corpse is an encounter with our own death, which becomes palpably real, even under conditions when it seems that you no longer react to the sounds of air alarms or explosions nearby. The black underpants covered with earth force us to confront the limits of art. Because of her own powerlessness against endless violence, Libkind has turned herself into nothing.

Katya Libkind, From the Sleeping during curfew, 2024. Pencil on paper, 21 × 29.7 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

What should art be like during wartime? Does it have to give anything to society at all? Every new day in Ukraine brings a new context that can completely change one’s impression of art and life itself. Where are its limits, or are they beyond the boundaries of each individual? Libkind responds with a poem:

Today, the universe began for me

here is my passport

eternal memory

eternal memory

eternal memory…

every woman

no man

eternal memory

eternal memory

—September 2024

In a statement for the Secondary Archive. Read more: https://secondaryarchive.org/artists/katya-libkind/.

Ibid.

See Jury Rupin’s 1973 photograph Solitude https://moksop.org/en/art/artworks/jury-rupin-solitude-rupj-59-1973/.

kasia_ia Instagram post (March 15, 2022): https://www.instagram.com/p/CbHsD3utsYP/?igsh=eXFwNnl5OWkxcmZ3.

Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, trans. Leon S. Roudiez (New York: Columbia University Press, 1992), 4.