The tiled floor of Konsthall C has seen hard use, both in the twenty years it has functioned as an experimental art space and, before that, as the common laundry room for the rental apartments in this suburb of Stockholm. Time and traffic have eroded the diagonal pattern of beige and dark-gray squares, and now the floor looks clean and utilitarian. This kind of straightforward durability is the appropriately mundane ground for the inaugural exhibition of Mariam Elnozahy’s first program as Konsthall C’s artistic director. Her two-year thematic proposition “Sacred Spaces” is balanced between a positivist understanding of the sacred as someplace metaphysically safe and an idea that the contemporary art institution might offer “a place to discuss religious pluralism.” The intervention arises in a febrile context: a long-running debate in Swedish courts over whether burning the Koran could be seen as a form of political protest; an extreme rise in gang-related gun violence—Sweden is now second only to Albania in Europe—with attendant media coverage often emphasizing immigration and ethnic identity, with overtones of politico-religious affiliation.1

It would have been easy to open a program along these thematic lines with something confrontational, but instead Elnozahy reproduced, inside the gallery, the meditation room from the UN headquarters in New York. The room was renovated in 1957 by the Swedish aristocrat and state economist turned unlikely international diplomat and UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld. Elected to the UN post because the Soviet Union vetoed the four people proposed before him as being too politically aligned with the West, Hammarskjöld ended up being so inconveniently committed to humanist idealism that his plane was allegedly shot out of the sky over the Congo during tense negotiations there in 1961 following the assassination of the former Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba.2

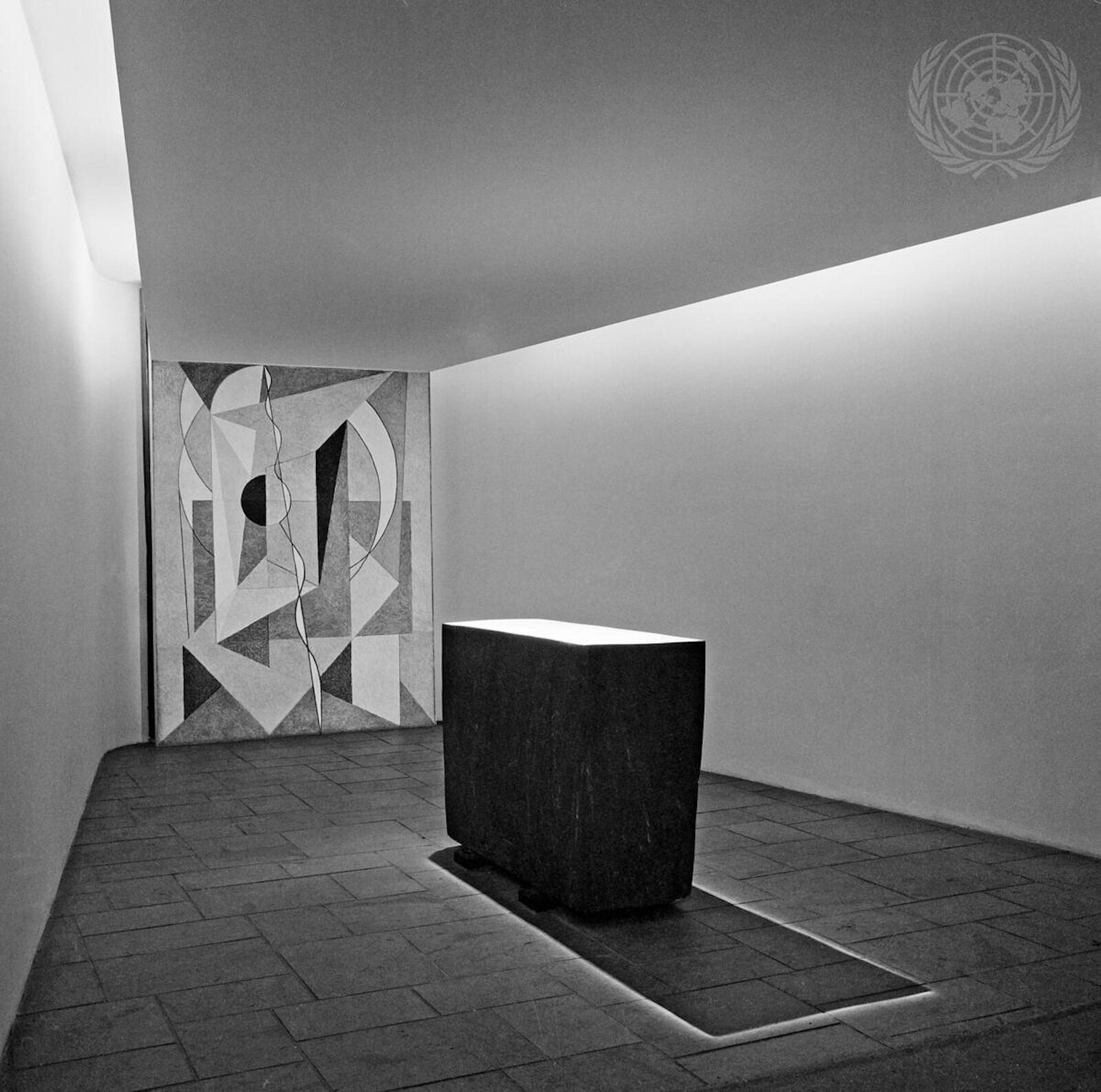

The installation is sparse, like the room it mirrors across the world. The team built a three-sided, open-ended white box on an angle inside Konsthall C’s industrial gallery, with a dropped ceiling to mimic the precise lighting conditions that were so important to Hammarskjöld. Konsthall C’s preparators made an exact copy of an abstract mural by an unremarkable twentieth-century Swedish painter named Bo Beskow, and commissioned a hollow version of the massive iron rectangular altar gifted to the UN by the Swedish monarchy. Simple wood and thatch bootleg copies of benches originally designed by legendary Swedish architect and designer Carl Malmsten are placed in contemplative rows. There is no trace of irony evident in the careful spatial doubling; the effect is remarkably peaceful. It appears to pay sincere homage to Hammarskjöld’s ambition: “There is an ancient saying that the sense of a vessel is not its shell but the void. So it is with this room. It is for those who come here to fill that void with what they find in their center of stillness.”3

Yet it is not true that the room is empty. In fact, it is full of competing symbols. Sweden’s mines provided 43% of the iron ore used by Nazi Germany between 1933 and 1943.4 This trade, and the access to Swedish railways to ship iron from occupied Norway, provided a lifeline for Germany throughout the industrialization of the Nazi war machine. For the Swedish monarchy to “gift” a massive block of iron ore to serve as an altar to stillness and peace at the UN Headquarters a mere twelve years after the end of the war is the height of diplomatic irony.

Bo Beskow was the fourth son of Natanael Beskow, a leading Swedish theologian, radical pacifist, and spokesperson for women’s suffrage. Beskow junior is best known for stubbornly and painstakingly mastering medieval glass-making techniques to get the perfect color in his magnum opus, a series of thirty-seven stained glass windows in the Skara Cathedral. Malmsten—who was commissioned by the Waldorf Astoria to design their interiors and by the UN Council President to furnish his chambers in Geneva in the early 1930s—was fiercely opposed to Swedish functionalism, characterizing it as a “smooth, imported, anti-traditional style, mechanically dry and founded on false objectivity” [emphasis added].5 Capitalism in direct alliance with fascism, idealistic Christianity, and staunchly traditionalist aristocratic design aesthetics—these are the deep footnotes to Hammarskjöld’s notion of a “void.”

What is remarkable about Elnozahy’s proposition—which she makes on the sole authority of her role as artistic director, and without recourse to the creative license of an invited artist—is that despite its carefully critical mise-en-scène of the Swedish contribution to the UN’s questionable peace-keeping mandate in the Global South as it fails to intervene in a genocidal conflict in Palestine, it still works. The room is still used by ordinary people in the neighborhood seeking a place to pause and reflect in silence. The Stockholm-based independent curator Mmabatho Thobejane ran an entirely sincere and well-attended workshop about non-denominational altar practice as part of the city-wide arts festival September Sessions. People spilled out of the room and out the door at talk on Swedish Internationalism in diplomacy by Pierre Schori, a close associate of Olof Palme and a revered liberal diplomat.

I read Elnozahy’s gesture in this moment of extreme polarization in public debate as an admission that any discussion of religious pluralism in the West must be conditioned by the values that underpin its regimes of sense. Yet the exhibition maintains that it is nevertheless possible to use the gallery’s and the West’s understanding of sacrality to open a space for difference—in faith, in politics, in aesthetics. The most violent stages can be instrumentalized in service to subtle and multivalent forms of resistance. Hallelujah.

See Alex Maxia, “Teenage guns for hire: Swedish gangs targeting Israeli interests,” BBC News (October 17, 2024), https://bbc.com/news/articles/c1e85l701y3o.

See Göran Björkdahl, “’I have no doubt Dag Hammarskjöld’s plane was brought down’,” The Guardian (August 17, 2011), https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/aug/17/dag-hammarskjold-crash-goran-bjorkdahl.

See Konsthall C website: https://www.konsthallc.se/en/program/meditation-room.

Rolf Karlbom, “Sweden’s iron ore exports to Germany, 1933–1944” Scandinavian Economic History Review, vol. 13, Issue 1 (1965): 65–93. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03585522.1965.10414365.

Carl Malmsten pionjär och traditionsbevarare (Carl Malmsten, pioneer and keeper of tradition) (Bodafors: Svenska Möbelfabriker, 1963).