Jenny Holzer began making her ongoing series of “Truisms” in 1977. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, truism indicates “a self-evident truth, esp. one of minor importance; a statement so obviously true as not to require or deserve discussion. Also: a proposition that states nothing beyond what is implied in any of its terms.” The word “truism” means more or less the same thing as “platitude” or “cliché”—unremarkable, banal observations—but the fact of its orthography nudges it, just slightly, toward a charged moral terrain of reality and deception.

Today the word’s appearance, unlike its synonyms, reminds us how contentious such a notion of obvious and easy truth has become. The same statement is either widely repeated nonsense or unquestionable fact depending on who you ask. This has always been the point of Holzer’s text-based works. “Truism” underscores the tension produced by common sense and capital T truth that animates her scrolling digital billboards, engraved park benches, projections, and painting of redacted documents.

Making strange claims in the form of a brief declarative statement or maxim draws attention to the ways that sense becomes common (or doesn’t) and underscores how difficult, if not impossible, it is to produce statements that say “nothing beyond what is implied in any of its terms.” Take one of the most recognizable of Holzer’s “Truisms”: “Abuse of Power Comes as No Surprise.” Nothing could be more obvious. But then again, abuse of power is almost always a surprise or it wouldn’t be legible as abuse. And then we might ask: what power is not abusive? The maxim is an interesting political move. Its symbolic efficiency is questionable, but whatever power it has is due to its spare and contained language.

Accordingly, “WORDS” at Sprüth Magers’s New York City gallery is an efficient and attractive survey of Holzer’s career. In the space of two galleries, we are shown the Truisms in their different iterations as hand-drawn templates, granite seats, and scrolling LED signs (updated to generate text using machine-learning algorithms). Redaction paintings, and (confusingly) a bowl full of condoms accompany these other texts. The two LED sculptures—SO GOOD (2024) and BAD (2023)—are propped at casual angles amid a pile of rubble made from smashed benches. It is a difficult gesture to read. Making the textual fragments more fragmentary, pushing them over a line into the unintelligible, is arguably a way to approach questions of meaning, truth, and language raised by the truism itself. What exactly makes something make sense? And what makes it make so much sense that it becomes not just logical but true? Does truth need a certain physical structure for stability?

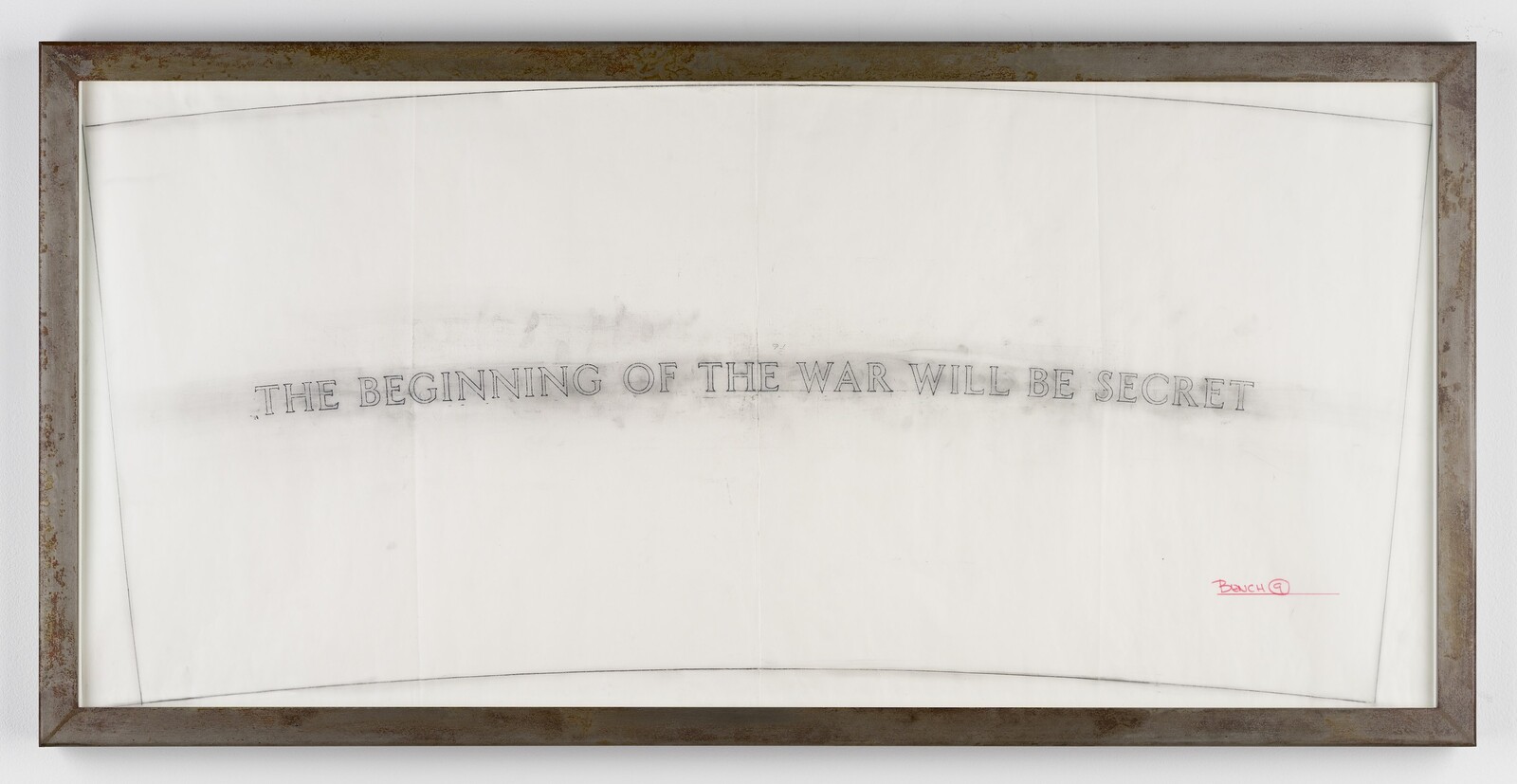

As one of the intact benches included in the show cheekily reminds us, “words tend to be inadequate” (2020). Many of these truisms are unexpected or disturbing statements. Take, for example, a line from the series “Survival” (1983–85) stenciled onto vellum: “silly holes in people are for breeding or from shooting.” Sentences like these retain a formal, grammatical, order that provides the appearance of absolute sense: a linguistic trompe l’oeil of sorts. To break up the basic material of her own practice in this manner is perhaps Holzer’s way of questioning the stability of textual meaning in general, drawing attention to the superficiality of what makes (as in produces) sense.

So what of this ruined form? Like many “ruins”, the smashed benches are fabricated—the engraved granite was intentionally destroyed by the artist, not broken in the course of use or removal or actual violence in the public sphere. The granite benches engraved with distinctly unheroic maxims are not the stuff of a monumental past; the atypical nature of this “ruinscape” distinguishes it from the man-made ruins long favored by European aristocrats as garden decorations. One of the best, if simple, points made by Holzer’s oeuvre is the importance of a dialogue between high-concept art and the vernacular spaces of advertising, public parks, or subway stations. Still, the weirdness of fake ruins is something that needs to be accounted for.

Ruins aestheticize the past through the presentation of the fragment: not the historical past, but a generalized and reified past from which something great can be retrieved or transmitted. Are the former benches meant to suggest the mythologized past—nostalgia for that which never quite existed—that makes up a large portion of the content of so much ultimately empty political speech? A fake past would be an appropriate setting for the LED sculptures SO GOOD and BAD, whose narrowly political slogans are derived from a two-party system in which candidates propose alternate paths back to better times.

Read this way, scrolling speech literally lying in ruins might be a bit on the nose as a formal gesture, but politically astute nonetheless. Unfortunately, I don’t know that I trust Holzer to be critical: the work seems to have drifted into a realm of sanctimonious, New York Times-led indignance. That truisms in the form of memes, yard signs, protest slogans, and tote bags (think “science is real”, “love is love”, “the future is female”) have played such a prominent role in degrading political analysis is not Holzer’s fault—she’s been writing in “tweet” form since the 1970s—but responding to this does seem like her responsibility.

The explanation given for this linguistic wreckage by the artist is unsatisfying: the broken pieces look like “what is happening on the news.” But there’s something significant going on here that can’t be ignored, if only because it gets repeated in the works on paper that constitute the majority of the show.

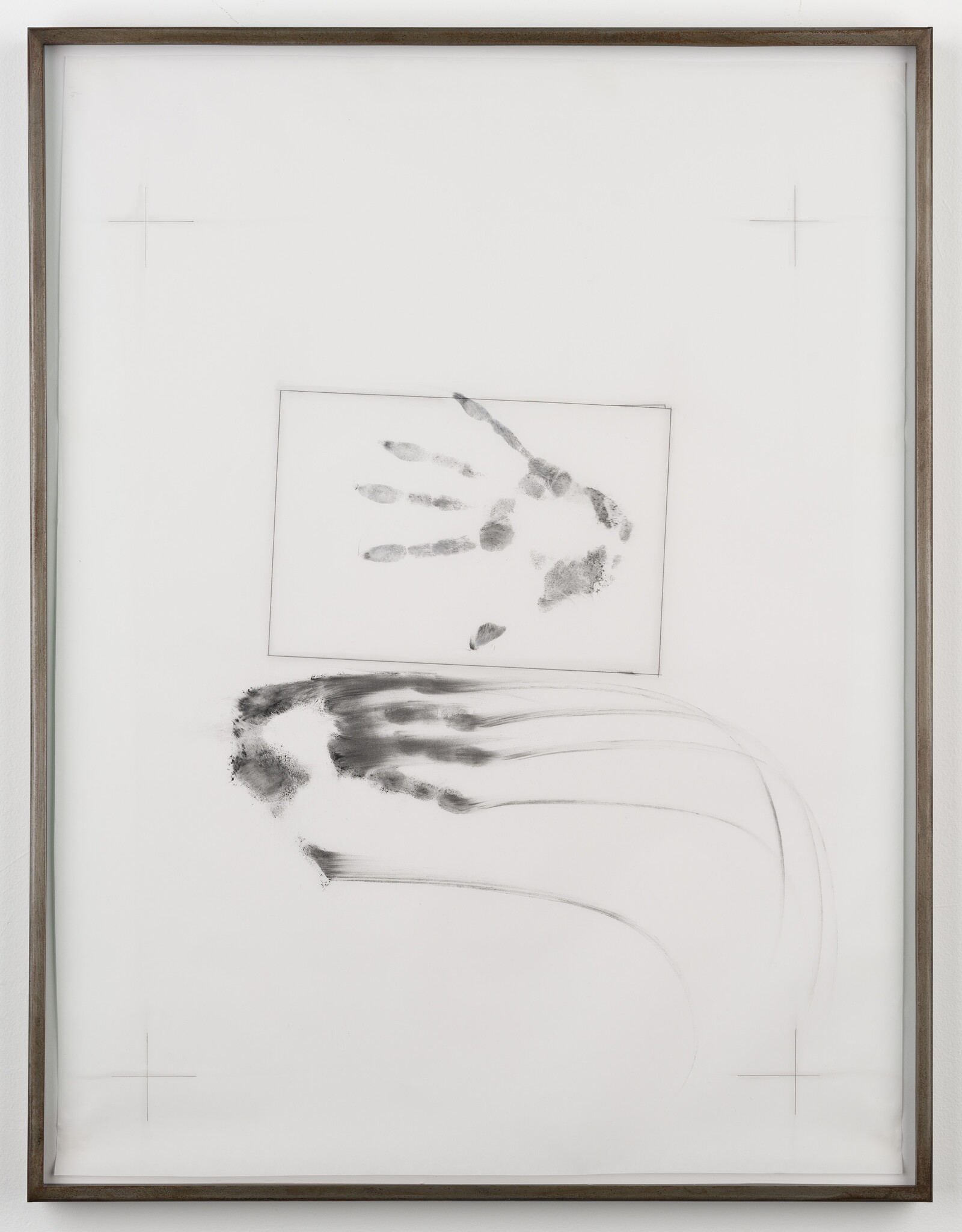

The second scene of this relative visual chaos is a supremely attractive collection of Truisms and other text-based work in charcoal, hung salon style in matching metal frames. All of them are at least slightly smudged. Many are the vellum templates for engravings that are both the final product and proof of process, and therefore organically retain the accidental marks of handwriting. But many of them have been taken over by handprints and marks made by dragging fingers, that have rendered whatever text might be there either secondary to the composition or fully illegible. It is possible that these marks (that would normally be erased) are a sort of return of the repressed that could be read in relation to the redaction paintings; a demand that we consider how much tidying up and erasure is required for a comfortable, untroubling, aesthetic existence. How this might condition us to trade ease of interpretation for transparency in politics.

But the pieces that resemble children’s finger painting outnumber this nuanced aesthetic. And the smashed benches, which required an elaborate professional demolition, suggest that the destruction itself is the more salient development in Holzer’s practice than any thought about the production-by-erasure of the finished sentences. This seems to be affective rather than strictly intellectual, a disappointment or frustration with the failure of language; the evidence of some messy, grasping process or aborted transformation. For Holzer, whose medium is public (if not “free”) speech and the slogan form, the political dead end of Liberalism might be impossible to fully admit. Being too smart to keep believing that the right words and reasons will finally win the day, but believing, still, that power must be abused to cause harm, must be supremely frustrating. I would start breaking stuff too.