There is a line of criticism that argues that Karl Marx’s Das Kapital (1867–94) is the great gothic novel of the nineteenth century. It’s a line that runs through an essay by the poet Keston Sutherland that, in a bravura piece of close reading, explores the stakes involved in the translation into English of the German word Gallerte. When Marx writes about “bloße Gallerte unterschiedsloser menschlicher Arbeit,” Sutherland argues, he does not refer only to “congealed quantities of human labor,” as the line is most often rendered in English.

He is in fact referring to a staple of German foods and cosmetics; gallerte, Sutherland explains, “was made from the off-cuts and the discarded bits of animals from early industrial slaughter processes. It was the stuff the bourgeoisie wouldn’t want to eat in its natural form, but which could be boiled down and turned into this great mush and then used in breakfast condiments or cosmetics.”1

Marx wants the reader to feel the full brutality of what capitalism does to laboring bodies. He wants to reveal the horror beneath the social codes by which the bourgeois protect themselves from the gory facts of the capitalist mode of production sustaining their existence. The bourgeois family home is built upon the jellied gore of the slaughterhouse. Marx wants to force the reader to look.

The “hyacinthine, ringleted, foggyvoiced” (Edmund White, of course) Hervé Guibert was certainly no Marxist; indeed, one of his closest friends was Marxism’s occasional bête noir Michel Foucault.2 But the imaginary of his phantasy was constructed at a young age from materials that he would later use to rent the veil of bourgeois propriety, and that seem to speak to Marx’s gothic metaphor of the slaughterhouse. Not incidentally, his father was a conservative and profoundly bourgeois veterinarian and slaughterhouse inspector who liked to pin postcards of the more morbid masterpieces of Renaissance painting on the walls of the family home. The critic Charles Teyssou conjects that it was Guibert’s father who gave him a copy of Vesalius’s 1543 anatomical treatise De humani corporis fabrica (On the structure of the human body) with its remarkable illustrations of flayed bodies, intestines, and raw stretched muscle, when he was a boy. From the start, Guibert was surrounded by an imaginary constructed from the bloodiest elements of the Catholic and medical corpus.

Guibert was not a Marxist, but he was, perhaps, the last in a line of aesthete traitors to their own class. A line beginning with Charles Baudelaire and whose mode of treachery consisted in assuming the manners and mores of the libertine aristocracy brought to baroque apotheosis in the work of the Marquis de Sade. In his final works charting the effects of AIDS upon his body and mind, as perverse as it sounds, the sense is that the disease somehow fitted into and allowed Guibert to complete an aesthetic project—one given expression in Foucault’s late work, exploring what he called an “aesthetics of existence,” and, by extension, an aesthetics of dying.

Guibert’s early work Suzanne and Louise (1980), now published for the first time in English in a handsome edition by the New York-based publisher Magic Hour Press, uses photography and text—Guibert called it a photoroman—to investigate the lives of his two maiden aunts who share lodgings in an old hotel particulier in Paris’s 15th arrondissement. Suzanne is a widow who has risen through the French class system, studied music, and read the great works of the French canon. Louise has been a Carmelite nun earlier in her life, a fact that appeals to the ascetic component of Guibert’s character. She has donated her body to medical science when she dies; Guibert, in a sentence combining compassion and cruelty, writes that “Her body which has never been touched, will be offered up for disembowelment and dismemberment.”

In a sense, Guibert offers his aunts up for a kind of flaying. At times, especially in his writing, Guibert’s will to shock can be affected. But here it mostly works to genuinely disturbing and perverse effect. Writing about himself in the third person, he says: “They perform, for him, a dramatization of their relationship. They seduce him; they are jealous. He keeps quiet and listens. They are amazed by the interest he shows in them, flattered, amorous. Suzanne says to him: ‘If you came to see us in the park, people would think you’re my sweetheart.’”

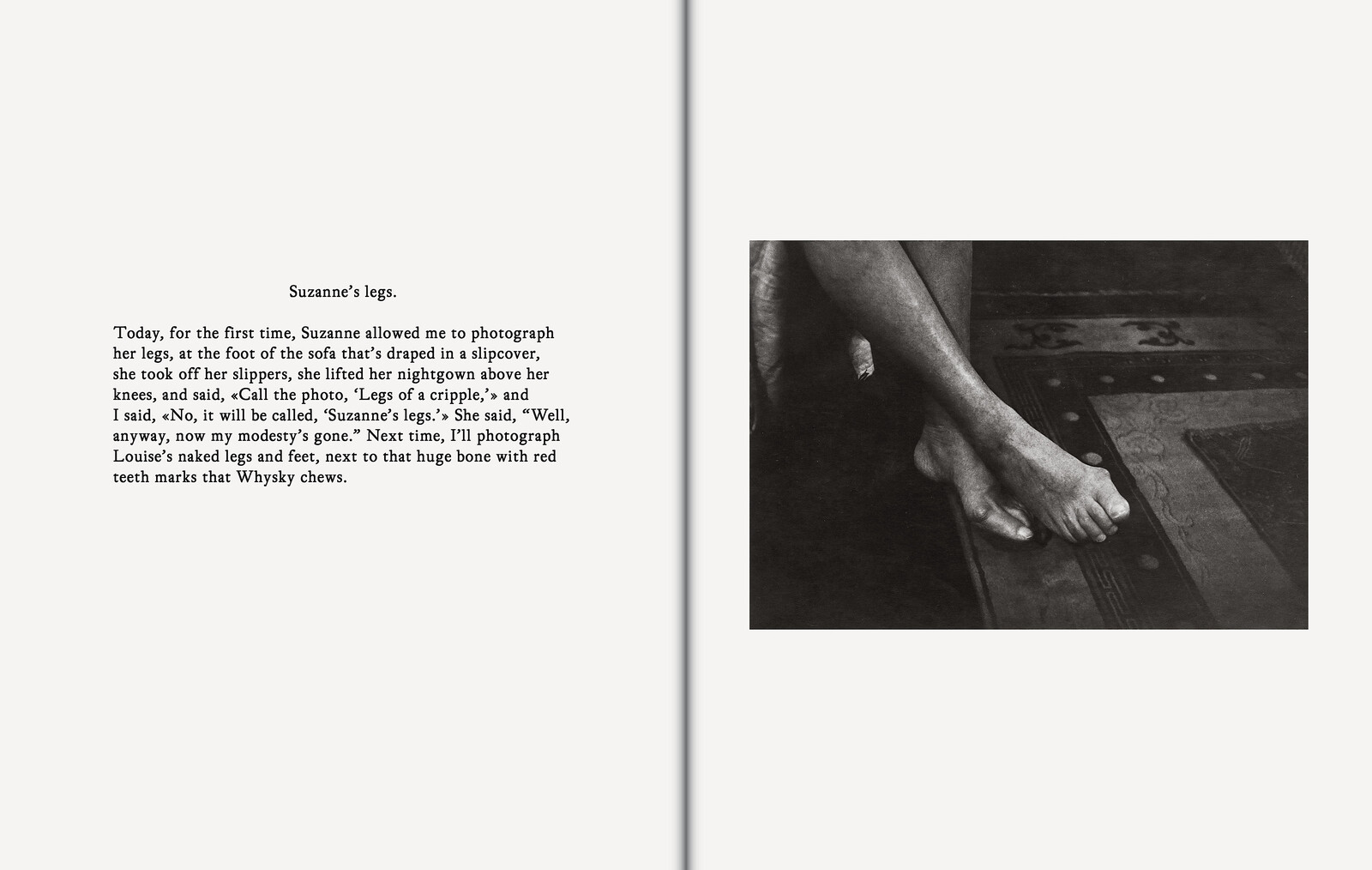

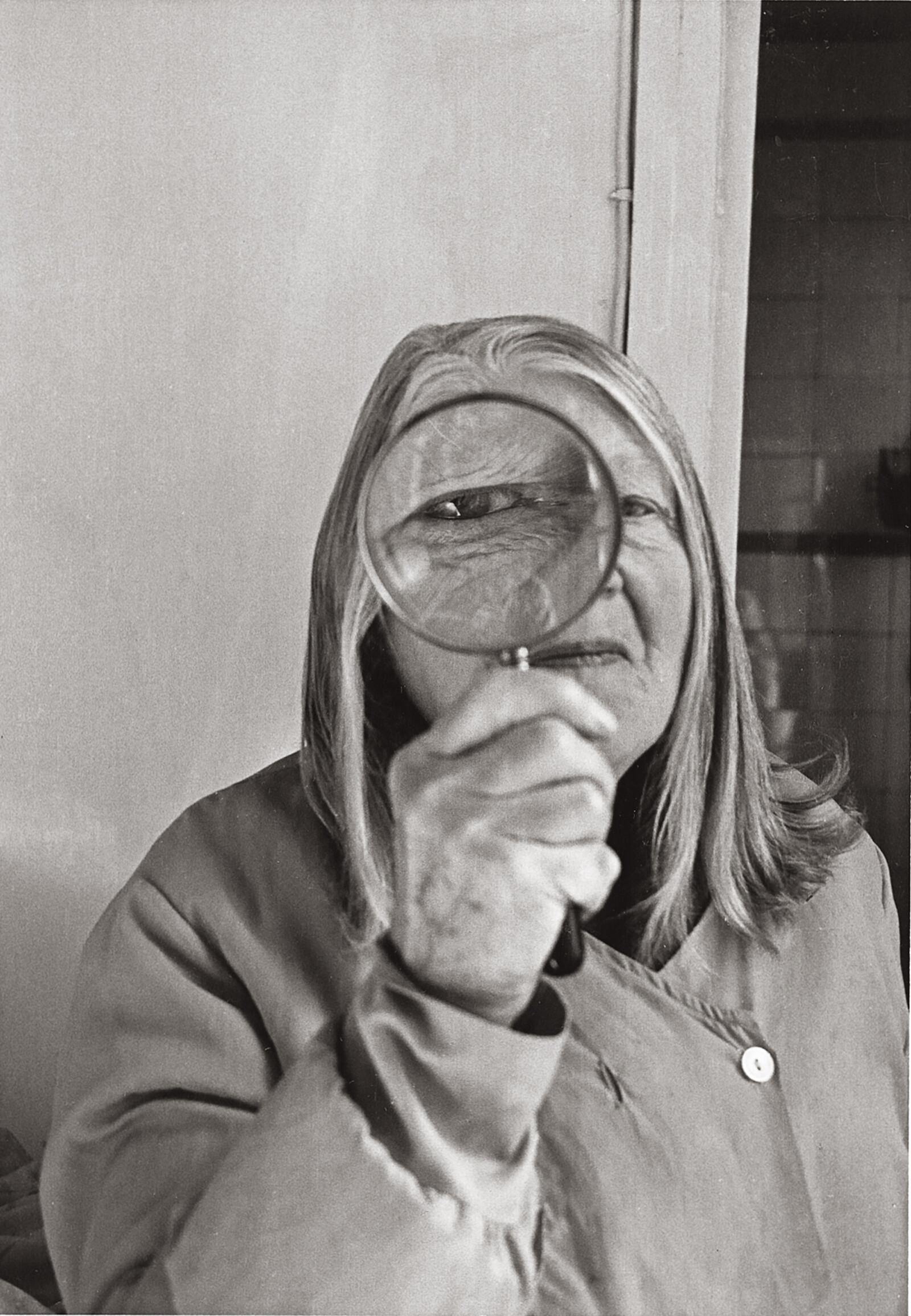

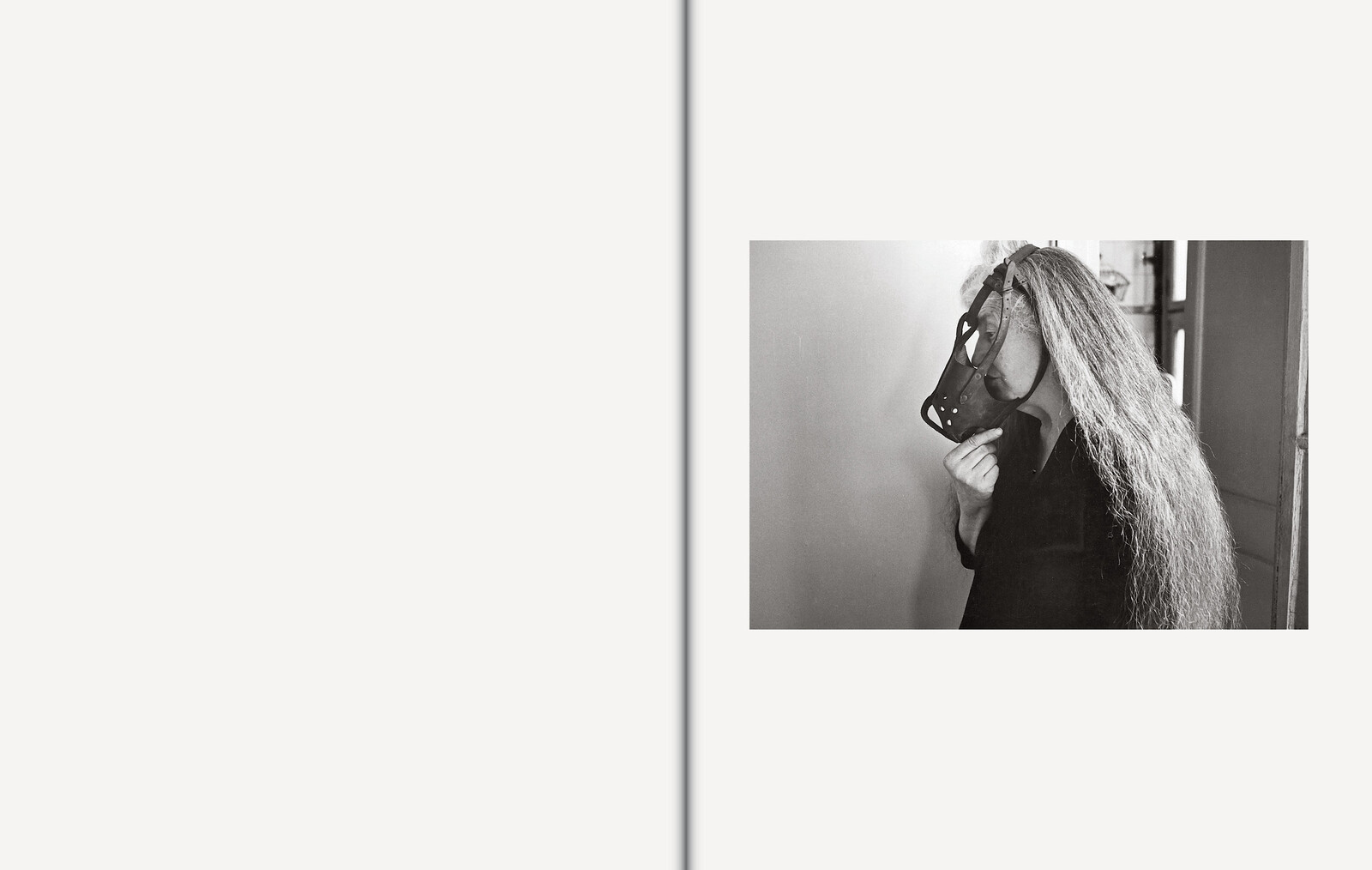

Guibert’s work is defined by an often merciless will to exposure. He is concerned with the latent sadomasochism in the two women’s relationship and in his own particular voyeurism. At one point, when Suzanne is holidaying at her country house, Guibert asks Louise to wear a dog’s muzzle and photographs her. It’s a strikingly disturbing image. Indeed, the book often enters into an oneiric register. Certain scenes are presented as documentary and then revealed to be constructions: the dog’s death, or an extraordinary episode describing Louise’s body being pushed around with other corpses in a huge glass tank of formaldehyde in the basement of the university by a man with a long wooden oar, like a demon in a Renaissance painting of the Last Judgement. Guibert takes delight in the power he holds over the aunts, excited by how close he can push them and his observations of them toward the inappropriate, baiting his imagined reader’s sensitivities. At least, that is true of the text. Excepting the muzzle images, the photographs are a slightly different matter.

If in his writing Guibert was most influenced by Thomas Bernhard, Sade, and Baudelaire, it is re-encoded categories from Jean Genet’s texts that come up most in his thinking about photography, namely “betrayal” and “love.” The prose is always inching around the narcissistic and perverse aspects of his love for his aunts, but the photographs are often cool, tender, haunted, and melancholic, possessing a quite different poetics. Yet the images themselves are subject to his affected perversity via the text. At one point he sends Suzanne a letter:

The letter I might write you could be indecent: it would be a love letter… My dream, of course, would be to photograph your body, with the same love I use to wash your hair, pluck your whiskers, or massage one of your aching muscles. Don’t ever be afraid. If you go blind, I will come and read books to you. And when you sense that you are dying, call me, I will come and hold you in my arms.

On one level, it appears to be a tender missive. But on another, I can’t help but detect something menacing in it, especially given the broader context of the work. It is a letter that sums up the book: manipulative, twisted, perverse, loving, ascetic, gothic, beautiful and uncompromising. With his aunts as fleshed marionettes, Suzanne and Louise is one of Guibert’s most fascinating performances.

Suzanne and Louise is translated by Christine Pichini with an introduction by Moyra Davey.

Peter Matthews, “How Not to Translate Marx,” The Berliner (December 2022), https://www.the-berliner.com/books/keston-sutherland-how-not-to-translate-marx/.

Edmund White, “Love Stories,” London Review of Books, vol. 15 , no. 21 (November 4, 1993): https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v15/n21/edmund-white/love-stories.