Robert Hazen outlined the theory that the mineralogy of planets and moons evolves as a direct result of interactions with life.1 While only a dozen mineral species are known to have existed when our solar system formed 4.6 billion years ago, today Earth plays host to more than 4,400, an indication that the chemical and biological processes enacted by organisms engender their formation. On a planetary geology scale, then, our interactions with rocks stimulate their development as much as they buttress ours.

This molecular symbiosis threads through the works in ikkibawiKrrr’s solo exhibition at Art Sonje Center. Since 2021, the trio—composed of Cho Jieun, Ko Gyeol, and Kim Jungwon—has explored the interactive and shifting boundaries between humans and the nonhuman natural world. The collective’s name comprises “moss” and “rock” in Korean, plus the onomatopoeic sound “krrr.” While previous bodies of work have centered on seaweed, grass, and moss, “Rocks Living in Rewind” sees the group hewing to that more abrasive component of their appellation, through a sustained focus on the South Korean peninsula’s disregarded stone statues of Maitreya–the bodhisattva believed to embody the future Buddha.

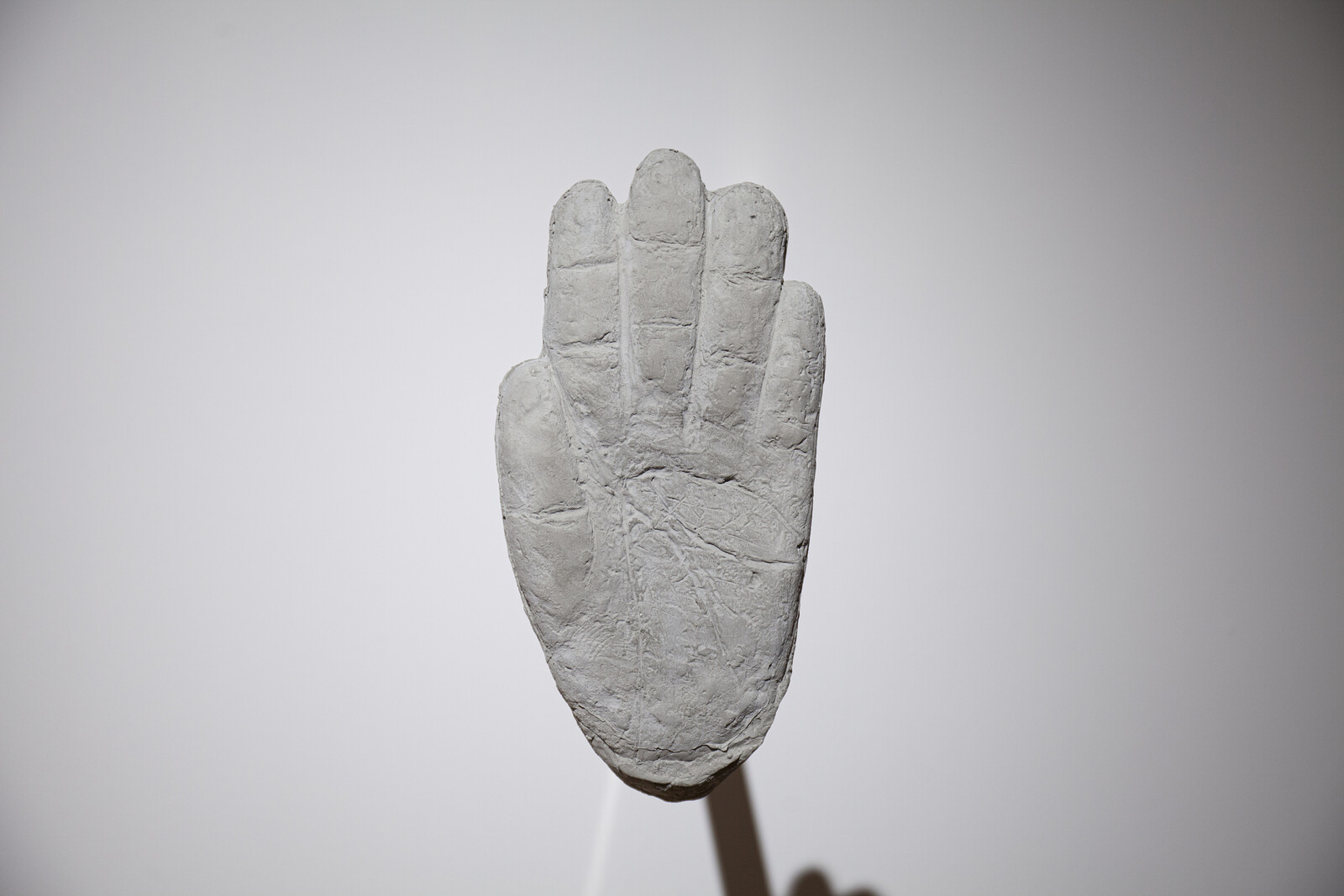

Visitors are greeted by Buddha High Five (all works 2024), a cement hand, larger than life and affixed to a 70 centimeter steel pole that protrudes from the gallery’s white wall. Installed around eye-level, the hand exhibits scars of its casting: scant effort has been made to amplify any lifelike qualities. ikkibawiKrrr imagined the hand as an intervention of critical fabulation: the scale is derived from a limbless Maitreya statue the trio encountered in the countryside, while the form recalls the abhayamudra, a gesture proffering reassurance and allaying fear.

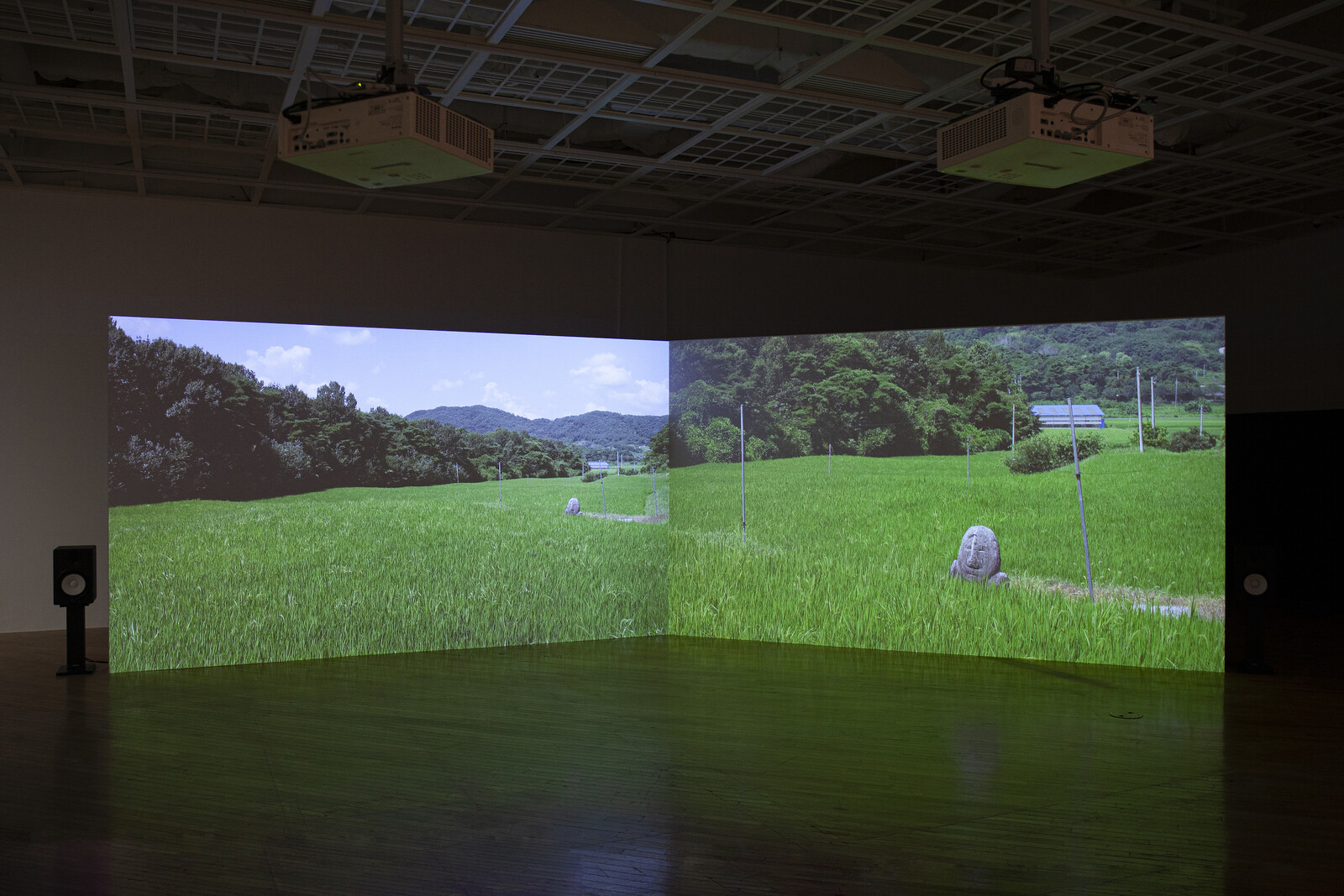

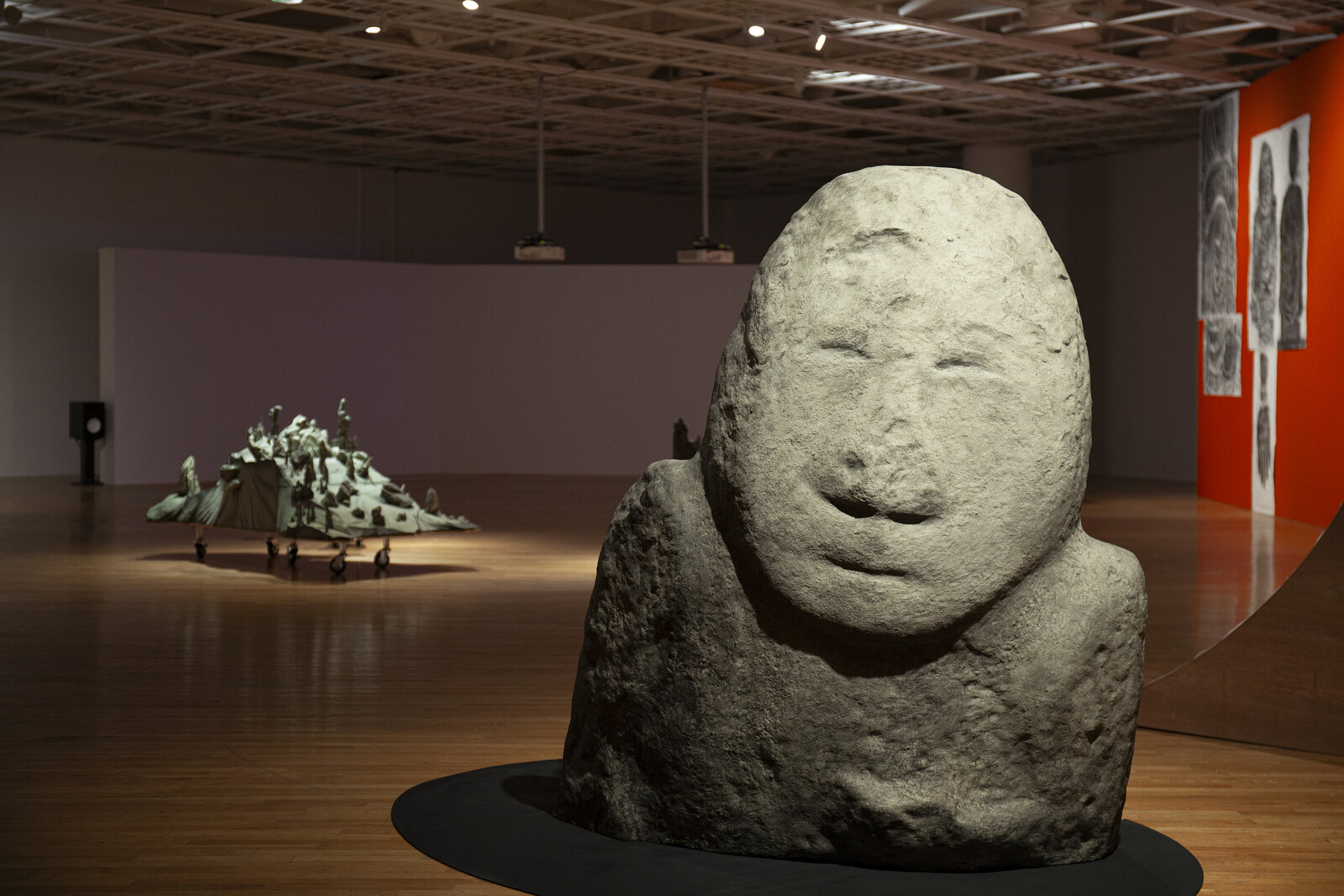

The exhibition’s title lends itself to two works: a two-channel video projected onto abutting freestanding walls, and a reproduction of a Maitreya discovered in a rice paddy. Dual images show sweeping vistas, close-ups of carved faces of rock statues, and contemporary trappings of industrialization. Accompanied by a score that oscillates between trembling and ambient, the video comprises footage the group shot over their yearlong journey visiting over sixty sites in search of the statues.

At its core, the video investigates how rocks morph over time, transformed subtly on the molecular level and forcibly by human intervention. As seen through ikkibawiKrrr’s lens, Maitreya statues stand sentinel in their overgrown enclaves while haul trucks cruise past, their beds full of crude material. Tourists swim beneath a power plant, and the energy-harvesting panels of solar farms span horizons. Meanwhile, lichen accumulates on forgotten statues. Through the video’s lively montage, ikkibawiKrrr parallels the erosion of the hand-carved stone manifestation of the future Buddha with the extraction of rocks and minerals under the auspices of industrial development.

Covering a third of the wall space in the gallery is Rock n’ Feel, an assemblage of charcoal rubbings on hanji, traditional handmade paper, of various body parts from a range of deserted statues. Hung against a safety-orange wall, the rubbings produce an exquisite corpse of outsized hands, angular feet, and rough-hewn rock torsos in cartographic detail. In front of this wall is the Maitreya reproduction, with its enormous head sporting an expression of tranquility, alongside Everybody Mountain, a miniature rendering of craggy peaks–the semblance of a landscape painting turned on its side and rendered in three dimensions. Like Buddha High Five, no gesture has been made to obscure the obvious human-made qualities of these sculptures.

The aesthetic of a stage-set runs through the exhibition’s scenography: more monumental frottage works hang on sloping columns constructed of exposed plywood; Everybody Mountain rests atop industrial swivel wheels; and the Rocks Living in Rewind sculpture sits in a spotlight of black carpet. The accompanying effect suggests that all of this could be disassembled in an instant. Whether we carve statues that promise eternity or produce works of art meant to archive the statues’ erosion, our tributes to longevity pale in comparison to the permanence of stone.

Indeed, the exhibition’s title is itself a provocation of the relationship between stones and time: one must accept the conjecture that rocks are living in order to contemplate what it might mean for them to enact such existence in rewind, as the show’s title proposes. Embodied within the statues—and within ikkibawiKrrr’s engagement with them—is as much a collapsing of interwoven timescales as a tacit understanding of our reciprocal evolutions.

Robert M. Hazen, et. al., “Mineral Evolution,” American Mineralogist, vol. 93, issue 11–12 (November 2008): 1693–1720.