This survey of Nástio Mosquito’s work from the early 2000s to the present begins, before it begins, before it begins. This cascade of overtures starts in the entrance hall of M HKA, which doubles as a reading room. In front of one of the bookshelves, a small cubicle monitor sits on a plinth: it shows Mosquito delivering a speech in the Senaat, one of the two chambers of the Federal Parliament of Belgium.

Partly because he is wearing a dark gray shirt and Malcolm X glasses, but mainly because of his charismatic voice and comportment, Mosquito evokes a long line of great Black orators from Frederick Douglass to James Baldwin, as he switches between booming and almost whispering. It’s as if different registers of speech—the serious and the comical, the authoritative and the offensive—have been chopped up and mixed into a salad of address. He offers casual salutations that range from the N-word to “Ladies and Gentlemen.” After discussing the temptation to cite John F. Kennedy, he does so. Performative self-contradiction is the foundation of his act.

It becomes clear that Mosquito is also tapping into a long line of great Black tricksters, from Anansi to Richard Pryor. His puns deflate authority and question the meaning of “power.” If only this speech could have been delivered during a regular session of the Senaat; instead it was for the opening of the 2017 exhibition “Superdemocracy” on its premises. The final absurdist touch is delivered when you read the title: Gym Membership Revoked.

Up the stairs and just outside the gallery doors, we encounter another small cubicle monitor showing a five-minute video. I am Naked—dated 2005 and the earliest work on display—shows Mosquito in a windowless, basement-like space seen through night-vision. Topless, he rants in Patois at the camera—that is, towards the guard who is the viewer—while pacing back and forth: words of anger, resistance, defiance. Manifesting tropes of Black masculinity, including those that precisely fit into the narrow scenario of surveillance and imprisonment, the work foregrounds its own ambivalence. Is it a straightforward evocation of rebellion and struggle for emancipation? Or does it, on the contrary, elicit precisely this expectation—and the viewer’s enjoyment of such performances—to play off content (the rant) against framing (the gaze)?

Finally inside the exhibition space, one possible answer comes in the form of Nástia’s Manifesto (2008). Just as Patois and CCTV are triangulated in I am Naked, here it is Russian-accented English (Nástia is the Russian male version of the artist’s name, à la Sascha or Nikita), and the language of online media. Feeling like a TEDx talk translated to Tik-Tok, the manifesto also mimics the truisms and slogans of designer Bruce Mau’s 1998 “An Incomplete Manifesto for Growth.” Mosquito made the work while living in Luanda (nowadays he’s based in Ghent). In the aftermath of Angola’s civil war, there were hopes for a better future. But new global antagonisms were already playing out in the country, foreboding the shift from a bipolar Cold War order to a multipolar one. Nàstia’s Manifesto heralds our time, in which social media gurus’ life hacks, populist politicians’ dumbed-down slogans, and mercenaries’ cocky pep talks (with or without a Russian accent) are part of the same continuum.

As one steps further into the show—it is organized as a one-way circuit—the cascade of overtures gives way to fractal personae and scenarios in which reality clashes with absurdity, mimicry with parody. A.L. Moore Campaign Room (2016–19) draws us into the strange world of A.L. Moore, a populist-autocrat heading the fictional African nation of Botrovia. Stacks of plastic chairs sit next to rolled up carpets and packets of placebo drugs spilling out of an air-lifted crate. On a small monitor, Mosquito/Moore practices a speech in chinos and business shirt, interspersed with fly-on-the-wall shots of him on the toilet wearing a dashiki and making voice notes, or lost in thought on a hotel bed. He complains over the phone about the escort service that was supposed to be Brazilian but turned out “Czechoslovakian,” even though, as he muses, the country doesn’t exist anymore. It all feels like a comedy dystopia dreamed up by SF-writer Tade Thompson, only that it’s not set in the future.

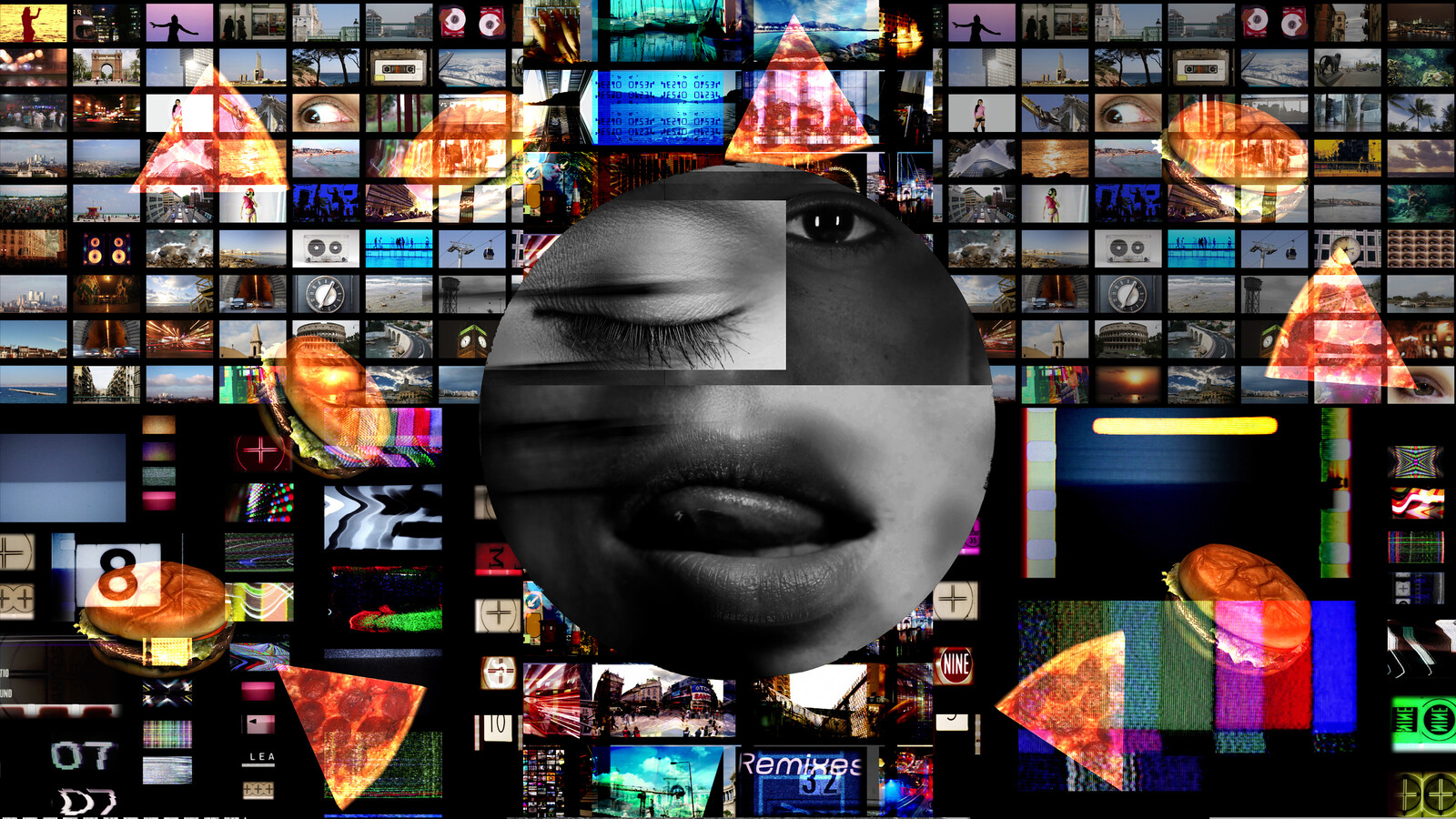

King of Klowns (2024), an hour-long stream of images, is shown on flat screens arranged in a circle and surrounded by plastic sunbeds with headphones, like an ambient lounge in a sanatorium. Directed by regular collaborator Vic Pereiró, the video is a tongue-in-cheek portrait of the many facets of Mosquito, including his music and his performances, intertwining his activities with a maelstrom of found footage from around the world. The duo go one step further with The Pantheon (2024), a work expressly dealing with the ownership and appropriation of images and ideas. Multiple projections thrown onto an improvised tent structure show everyone from William Burroughs to Marina Abramović cut-and-pasting their own and others’ work with or without acknowledgement—it’s a celebration of cultural contamination and image-theft.

GIZ #3 (2024) fills the biggest room in the show. All-caps poetry covers two of the walls (“STEP DOWN, NO AMBITION, HUMBLE / LOOK AT FEET NO DEFEAT THERE COMES PROVIDENTIAL STUMBLE”), while a third is left blank so that the audience, using available chalk, can fill it in with their own confessions or demands. Yet this space meant to prompt linguistic interaction feels contrived, and literally empty.

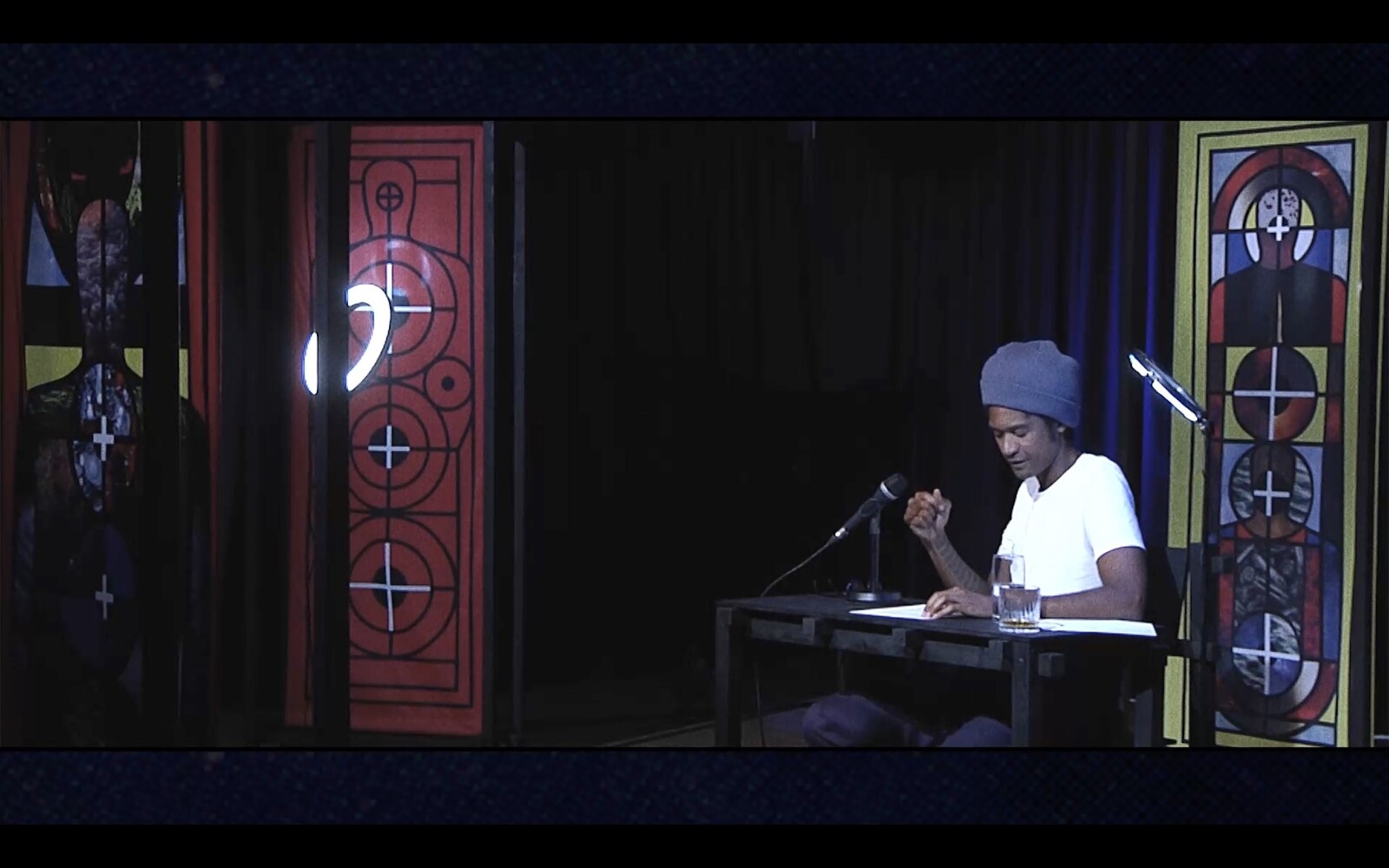

Maybe that’s the anticlimax just before the magic resuscitation that this show needed. The final room—the video installation Let Me Read You Roughly, documenting a reading session that took place in Munster in 2023—brings out all the charisma and charm in Mosquito’s approach. Reading a story about how to kill a friend, he addresses guilt, failure, the debunking of what makes “identity,” all the while speaking with panache and the warmly resonant, rollicking cadence of a seasoned storyteller. At one point he says, obviously about himself: “He would love to be a stand-up preacher. He is not. He has no doctrine. He has no jokes. Not good ones.” Which amounts, in my book, to a precise ex negativo definition of what really makes an artist.