August 17–November 24, 2024

Referring to the cà phê võng providing rest and refreshment to drivers on Vietnam’s provincial highways, this first institutional survey of Art Labor’s activities, curated by Celia Ho, opens with an invitation: to sit (or lie) on a hammock and drink Vietnamese coffee brewed from robusta beans grown in the country’s Central Highlands. The staging of this vernacular rest-stop performs a spatial reconfiguration. No longer are we in Hong Kong, but somewhere in Tây Nguyên, located within the Southeast Asian Massif known as Zomia, its complex textures expressed by a chorus of sculptures, installations, and instruments created by Art Labor—founded in 2012 by artists Thao Nguyen Phan, Truong Cong Tung, and Arlette Quynh-Anh Tran—and collaborators from the Indigenous Jarai community, with whom Art Labor have been working since 2016, alongside invited artists. Among them is musician and artist R Cham Tih, whose standing bamboo instruments in the gallery embody the recuperation of lost Jarai musical traditions through restorative innovation. While K’loong Put (2024) is a traditional xylophone, albeit with additional notes, Klek Klok (2024) is a new design drawing on traditional bamboo gongs used to deter wild birds from the fields.

A dialectics of loss and recovery infuses this exhibition, starting with its title. A cloud chamber refers to the scientific method of using vapor within an enclosed space to visualize particle movements, recalling both the Jarai cycle of reincarnation, where souls pass through seven lives before evaporating, and the spectral scent of coffee in the room. The Central Highlands accounts for Vietnam’s place as the world’s second largest producer of coffee, which the French introduced in the nineteenth century, a position established after the Đổi Mới economic reforms of the late 1980s. The region’s forests were felled to make way for plantations growing crops including coffee, peppers, and rubber. People from the lowlands migrated to work in the industry, extending assimilation campaigns that occurred in the mid-twentieth century, when the governments of both North and South Vietnam encouraged settlers to the region, which continued after reunification in 1975 under communist state planning. Impacting Indigenous and minority groups, these transformations extended a process of development characterized by resource commodification, population displacement, and biological and cultural erasure that began during the colonial era, including deforestation that intensified amid the Vietnam War, as the highlands became a strategic site for the US army, which rained chemical agents over the land, and the Vietcong. (The exhibition’s title also recalls the cloud-seeding operations conducted by the Americans to induce heavy rain over the Ho Chi Minh Trail.)

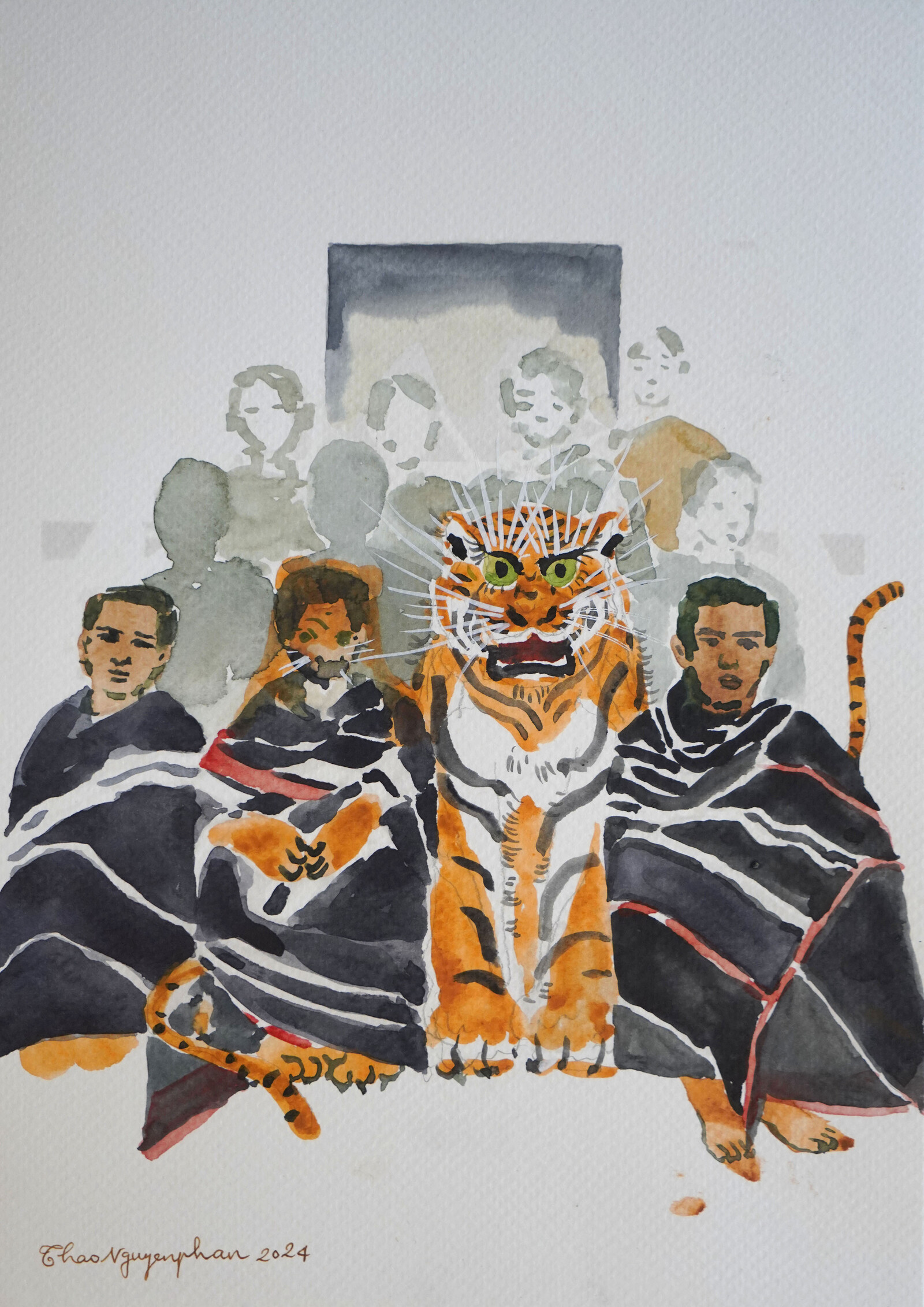

Used to train pepper vines, a series of concrete pillars arranged into a grove in one corner of the gallery highlight the link between past and present exploitations. Often repurposed due to the scarcity of wood, traditional wooden pillars can be seen in archival black-and-white images of village structures that appear in Thao Nguyen Phan’s Foret, femme, folie (after J.D.) (2024–ongoing). The work is presented in a space closed-off by a curtain of wooden beads made from crop trees arranged into a circular pattern, by Truong Cong Tung, aptly titled Long Long Legacies (2021–ongoing). Ostensibly co-authored with European anthropologist Jacques Dournes, Foret, femme, folie comprises a slideshow of photographs taken by Dournes between 1946 and 1970, and Phan’s watercolor responses, including portraits of bare-chested women and near-naked working men, whose discomfiting capture by a European gaze is countered by Phan’s illustrated reflections. Recalling tales that imagined the Central Highlands as a place populated by fearsome animals and spirits, faces transform into tigers or dematerialize altogether as if in a process of fantastic metamorphosis: a projection charged by an intimate curiosity that amplifies Phan’s own position, along with Art Labor’s other members, as a member of Vietnam’s Kinh majority.

Connections to the present continue in another photo by Dournes showing a man playing the k’ni mouth fiddle. The same instrument is positioned on a table in the gallery laden with wood-carved sculptures by Jarai artists, including a mottled blue water buffalo by Puih Gloh, one of the first to work with the collective, and a chameleon by Puih Han, a young Jarai artist who chose to remain in his village and train as an artisan rather than seek opportunities in the city. Each sculpture seems to respond to Long Long Legacies, where the biological and cultural diversity of an ecosystem, a homeland, has become modernized into a composition of standardized units. Arlette Quynh-Anh Tran’s video installation, The Galaxy of Electrified Heat (2024), speaks to the double-edged sword of this ongoing imposition. Presented on the other side of a wall made from fertilizer bags stained red with soil by Tung (From a land long lost to a land dwindling, 2018), thermal camera footage of the land surrounding a hydroelectric dam in the highlands is projected onto two walls, its pictures reflected and refracted by a hanging mobile of curved mirrors.

Often built by states seeking to modernize after attaining independence from their colonizers in the twentieth century, hydroelectric dams have proven catastrophic to ecosystems and communities while providing electricity and employment. This reflects the Catch-22 of developmental geopolitics in the postwar era, which Kwame Nkrumah defined as neo-colonialism given how membership to the global economy hinged on modernization according to international (read: western, imperialist) standards. No surprise, then, that the UN, the EU, and the Agence Française de Développement have all been involved in hydropower projects in the Central Highlands this century. Local communities have pushed back against their incessant proliferation, which has caused grave environmental damage and forced Indigenous communities off their land—but another chapter in the history of a region that Art Labor visualizes as an enmeshment of scales spanning past and future, local and global, and, perhaps most crucially, land and state.