November 28, 2024–February 25, 2025

In 2020, the group exhibition “OTRXS MUNDXS” offered a snapshot of Mexico City’s young artists and collectives. Whereas that first show felt overly ambitious, occupying the whole of Museo Tamayo and adopting a theoretical framework that attempted to define a generation, the latest iteration goes in the opposite direction: abbreviated to a few galleries and the central patio, and lacking any coherent sense of structure. The memorable (and sizable) installations by individual artists that were a feature of the first show are here replaced by a more scattered approach that conceives of the museum as a musical instrument, to the detriment of the art displayed within it.

The exhibition begins in the central patio, where a MIDI-controlled pianola has been programmed to play Conlon Nancarrow’s Study No. 21 (1948–60)—the piece is notorious for its intense speed and posthuman notation—once every hour. On my visit, however, it wasn’t working. Two sculptural speakers nearby played a combination of music, sounds, and noise selected by three radio collectives: Radio Noche, Radio Nopal, and Radio Imaginario. Abraham González Pacheco’s Windborne Message (2024), a series of beige polyethylene curtains hanging at different heights and embroidered with fists, roses, and scribbles, offered a scenography of sorts. The audio continued throughout the day, interrupted only by five-minute silences during which the Nancarrow should have been playing. It felt indicative of the broader incoherence of this deliberately “cacophonous” show. This empty stage appeared to have been set for a spectacle that left no traces, and which lacked instruments, performers—at times, even an audience.

Human is the Question (2024), a large, colorful mural by Oaxacan artist Andy Medina, is displayed in the main gallery spaces. Beneath its interlocking abstract shapes are two not-quite-equal sentences: “humano es la cuestión” (human is the question), and in English, “is human the question,” no question mark. The combination has the feel of a United Colors of Benetton ad from the 90s, the golden age of multicultural “we are the world” optimism. Nearby, a printout of a long, messy text responding to the mural is held in a basket hooked to a small metal table with power sockets and a fire extinguisher. Accesorio Espacial AE-EX-01 (Museo Tamayooo) (2024) is architecture and design collective APRDELESP’s contribution to the museum’s infrastructure—its original architects had apparently neglected to consider phone charging and fire safety.

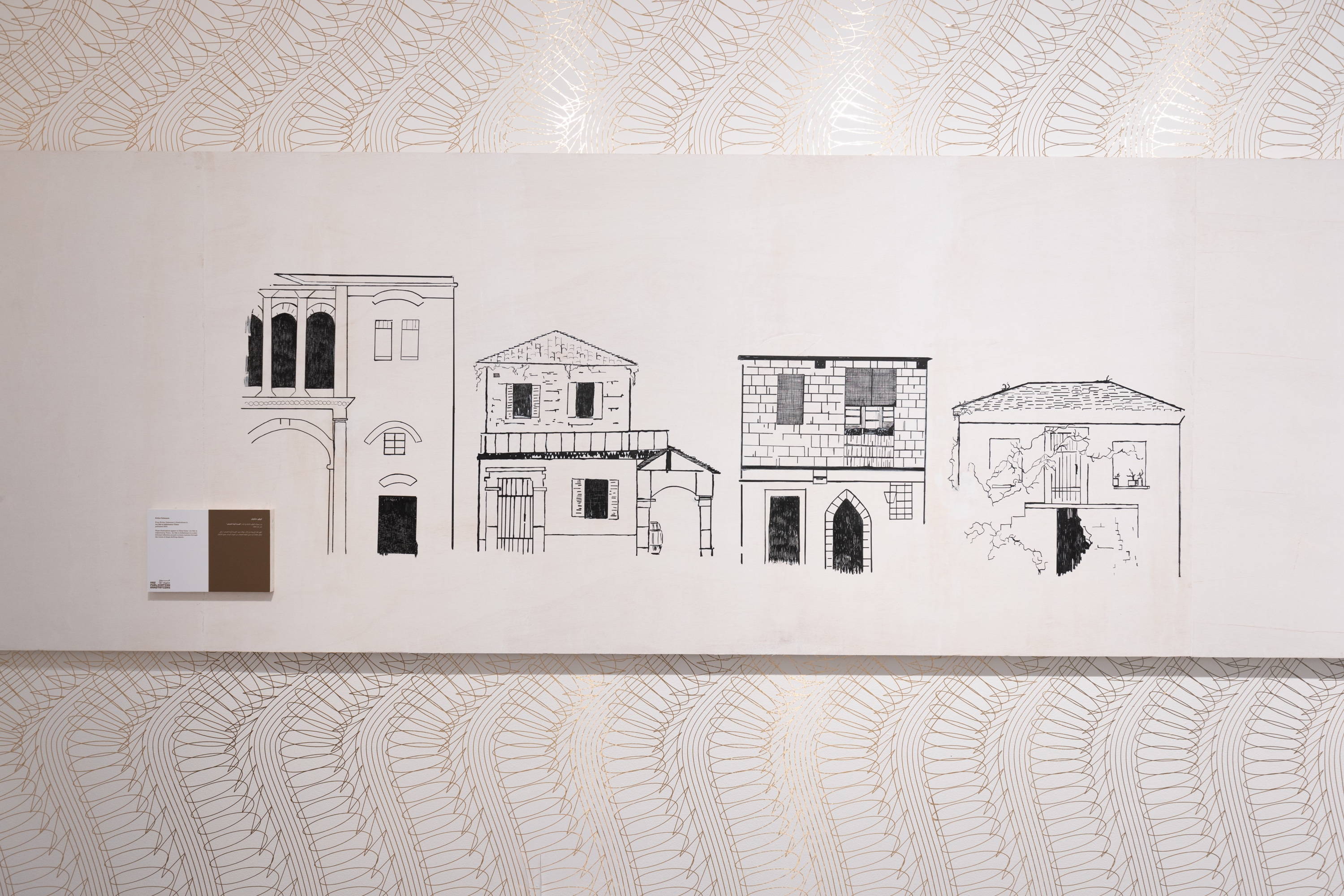

Indeed, “OTR^S MUND^S” is afflicted by a more innocuous version of institutional critique—you could call it “institutional navel-gazing”—with a number of contributors tussling with the building and its bureaucracies. Hooogar, an artist collective from Guadalajara, has intervened by changing the name of the institution to Museo Tamayooo in the exhibition’s wall texts. There are a series of mini-golf stations themed around the museum and the surrounding Chapultepec Park, a museum administrator’s signature scratched into a wall along with drawings based on an employee’s arm tattoos, archival blueprints of the building, and an “audio portrait” of the museum that broadcasts sounds recorded within its walls onto its outdoors patio. Some of these works are funny, but the self-referentiality gets tiring pretty fast.

The audio components of this show ran the gamut from music to noise: many, like the Nancarrow piece, were intermittent. Calixto Ramírez’s video performance How Can I Say It (2024), for instance, played for 45 seconds once every half hour. This felt more indecisive than speculative, timid rather than generative.

That was radically not the case, however, at Maggie Petroni’s hyper-staged (2024), an elaborate and heartfelt show-within-a-show engaging with the museum’s collection. Petroni crammed this amorphous office space, growing like a tumor off one gallery and delineated by unfinished wood-paneled walls, with abstract geometric, op- and kinetic art, most of it from the 1970s, including some big names like Eduardo Terrazas (of the few living artists shown in the historical “Abstractions” section of last year’s Venice Biennale).

With its low-lights, worn-down office furniture, and knick-knacks including a Titanic (1997) movie poster relocated from elsewhere in the museum, Petroni’s inversion of taste felt provocative against so many self-circling gestures. Artists like Terrazas usually hang on the minimalist offices of the people who run the city’s museums, but in Petroni’s dystopian quarters, they looked entirely different, shoddy, alive. Terrazas’s 2.50 (1974–2013), from the series “Tables”, a colorful Mondrian-ish composition made in the Wixárika traditional technique of wool thread and wax, looked downright hideous with its Brat-green center and loud red edges. Hanging on a half-finished Halloween-orange wall, and shown opposite a portrait of a dog, the clash was exhilarating. For the first time in my life I was excited to see a Thomas Glassford piece, Monstera Deliciosa, Foramen Sub Tributo (Silver Mandarin) (2014), a botanical sculpture made of overlaid, highly reflective anodyne aluminum leaves, hanging in the corner of a tiny cubicle painted chroma blue.

I was also taken by Aureliano Alvarado Faesler’s Triptych of Stages (2024), three enchanting small-format paintings, both realistic and dreamlike, two of them apparently based on behind-the-scene photos of a staging of Madame Butterfly at the sumptuous Palacio de Bellas Artes, and directed by Alvarado Faesler’s aunt, Juliana Faesler. But the triptych has not been given its own wall; instead, it is scattered all over the galleries, one part hanging in the poorly lit wasteland behind Petroni’s backroom.

Aside from those self-contained efforts, “OTR^S MUND^S” has all the pitfalls of group shows with none of the graceful alchemy of strange objects in juxtaposition. Indeed, its lack of structure and haphazard installation felt entropic: nothing seemed to relate in any meaningful way. Visiting felt like the institutional equivalent of mindless scrolling. The show’s lack of discursiveness and self-described “cacophony” felt insistent and repetitive, while its representation of “other worlds” was as shapeless and whim-driven as our stochastic modes of contemporary consumption.

Recently, someone I hold in great esteem argued to me, in paraphrase: “Contemporary art is a bit of a waste bin, a receptacle for drop-outs, drop-offs, those who feel lost or who failed at other areas of life, ex-politicians, ex-academics, that kind of crowd.” After the artist list for “OTR^S MUND^S” was released, I wanted to believe it would hold some of that promising interloper spirit: a makeshift curatorial safe-space in which freaks and drop-offs could share walls.

That hope deflated in late November as Sandra Sánchez, a writer invited to participate in the show, posted a letter on Instagram just days before the opening. In it she alleged mistreatment by the museum, going so far as to allege “psychological violence and manipulation.” Sánchez later staged a performance within the exhibition with a dozen supporters wearing T-shirts printed with enunciations from a manifesto of sorts she had authored on the ethics of art labor, “no gaslighting” among them.1 The gesture garnered support online, even as others dismissed the claims. However you read it, the debacle illustrated a growing gap between institutions and their artists and audiences. On social media, it was all about choosing sides: the latest reminder of our polarized lives.

See Sandra Sánchez (@phiopsia)'s Instagram post of November 26, 2024, and "Una ética (de trabajo) en el arte," Medium (December 4, 2024), https://medium.com/@phiopsia_56777/una-ética-de-trabajo-en-el-arte-33877400bca6.